Purpose

Malignant pleural and chest wall tumours pose significant clinical challenges and often originate from various primary cancers, including breast cancer, sarcoma, lung cancer, and oesophageal cancer. These tumours are highly invasive and prone to recurrence [1, 2]. They can cause pain by stimulating the periosteum, intercostal nerves, and parietal pleura innervated by somatic nerves, which severely affects patients’ sleep, appetite, and mental well-being, limiting their physical and social activities and significantly shortening life expectancy [3-5]. Effective control of pleural and chest wall tumours is essential for symptom alleviation and prolonged survival.

Currently, several treatment options are available for pleural and chest wall tumours; however, each has limitations. Surgery may alleviate pain in selected patients but is constrained by lesion extent and may result in chest wall defects and functional impairment. Additionally, not all patients are suitable candidates for surgery [6]. External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) can inhibit tumour growth; however, due to the characteristics of the chest wall tissue, it is difficult to irradiate precisely at high doses, and repeated radiotherapy is prone to cause serious complications [7]. Percutaneous cryoablation has shown benefits in pain management, but there is a risk of chest wall necrosis after cryoablation of tissues treated with radiation [8, 9]. Therefore, localised interventions with low recurrence rates are required to maximise symptom relief and improve quality of life in these patients.

Interstitial brachytherapy (ISBT) offers the distinct advantage of delivering a radioactive source directly adjacent to tumour tissue, enabling high-dose irradiation of the tumour while sparing surrounding normal tissues [10-14]. However, few studies have investigated the use of ISBT for pleural and chest wall tumours. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ISBT for these tumours, and to determine whether it offers a more effective and safer treatment option for affected patients.

Material and methods

Study design and population

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the institutional review board. Written procedural consent was obtained from all patients prior to brachytherapy. Patient and tumour characteristics, treatment details, and outcomes were collected from medical records.

This study included 21 consecutive patients with malignant pleural or chest wall tumours treated between January 2024 and January 2025. The inclusion criteria for ISBT were: 1) aged 18-80 years with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0 or 1; 2) pathologically or radiologically diagnosed pleural or chest wall tumours; 3) expected survival time exceeding 6 months; and 4) intolerance of or refusal to undergo surgery or EBRT. The contraindications included: 1) severe organ dysfunction; 2) coagulation disorders; 3) active infection within the past 3 months; 4) psychiatric illness; and 5) lesions invading the skin (to avoid refractory skin ulcers that may result from irradiation).

ISBT procedure

All patients underwent ISBT using a risk-adapted fractionation schedule (30 Gy delivered in a single fraction). This dose has been previously recommended in clinical trials evaluating HDR brachytherapy for thoracic tumours [13, 14]. A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan was performed to determine the optimal needle implantation trajectory, assess the dose to be delivered to the tumour, and evaluate adjacent organs at risk (OARs). Needle implantation was performed using either freehand or 3D-printed-template assisted techniques. After administration of local anaesthesia with 2% lidocaine, a steel interstitial needle was implanted into the tumour under CT guidance, following a trajectory determined by preoperative planning until the entire tumour area was completely covered. Following implantation, a whole-chest CT was conducted to confirm accurate needle placement and readiness for brachytherapy planning. CT slices were acquired at a thickness of 3 mm and transferred directly to the Oncentra planning system (version 4.5.5; Elekta Medical Systems, Sweden).

Radiation oncologists contoured the gross tumour volume (GTV) using all available diagnostic information sources, and dose–volume constraints for OARs were applied to optimise the brachytherapy plan. ISBT was administered to the 90% isodose line of the GTV at a single dose of 30 Gy. The prospective dose constraints for OARs were as follows: D1000cm3 of the lung < 7.4 Gy, D1500cm3 of the lung < 7 Gy; Dmax of the heart < 22 Gy, D15cm3 of the heart < 16 Gy; D0.035cm3 of the oesophagus < 16 Gy, D5cm3 of the oesophagus < 11.9 Gy; D0.035cm3 of the trachea < 20.2 Gy, D4cm3 of the trachea < 10.5 Gy; Dmax of the spinal cord < 10 Gy; Dmax of skin < 26 Gy; D1cm3 of the ribs and chest wall < 22 Gy, Dmax of the ribs and chest wall < 30 Gy. These dose constraints were primarily based on Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) protocols 0631, 0813, and 0915 [15-17].

After brachytherapy planning was approved, an iridium-192 (192Ir) radioactive source was temporarily introduced into the GTV using a Flexitron HDR afterloader (Elekta Medical Systems, Sweden). Immediately after ISBT completion, the implant needle was removed, the needle implantation site was compressed, and a chest CT was performed. After excluding pneumothorax and haemothorax, the patient was transferred to the ward for at least 24 h of observation.

Follow-up

Patients were discharged 3 days after the ISBT procedure, with follow-up assessments routinely performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after ISBT, and subsequently every 6 months until disease progression or death. Follow-up assessments were conducted during the regular outpatient visits. Radiotherapy-related toxic effects were graded according to the toxicity criteria of the RTOG and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) standards [18]. Tumour responses were evaluated 3 months after ISBT using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST, v. 1.1) [19], and were categorised as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD). Pain was routinely assessed using the numerical rating scale (NRS), a unidimensional measure of pain intensity in adults, categorised into five grades: 0, no pain; 1-3, mild pain; 4-6, moderate pain; 7-9, severe pain; and 10, unbearable pain [20, 21]. NRS scores before ISBT were compared with those recorded 1 month after ISBT.

Dosimetric comparison of ISBT plan and virtual SBRT plan

Virtual stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) plans were generated using the sliding-window intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) technique with the Eclipse treatment planning system (Version 16.0; Varian Medical Systems, USA). CT images obtained from the pre-ISBT plan were transferred to the SBRT planning system to create the virtual plan. The GTV was delineated by the same radiation oncologist who performed the ISBT contouring. GTV margins were uniformly expanded by 0.3 cm to generate the planning target volume (PTV). Respiratory motion was addressed by simulating clinical SBRT protocols, including the use of a vacuum mould for patient immobilisation. Although explicit respiratory gating was not employed in the virtual plan, the 0.3 cm PTV margin inherently accounted for microscopic motion uncertainties. For SBRT, the prescription dose was normalised to match that of brachytherapy, requiring at least 95% of the PTV to receive 30 Gy in a single fraction. Dose constraints for OAR were identical to those in the ISBT plan.

The dosimetric parameters used to evaluate treatment plan quality included: V100 and V90, defined as the percentage volume of the tumour target receiving 100% and 90% of the prescription dose, respectively; D95%, the dose delivered to 95% of the target volume; and the mean dose (Dmean) to the target volume.

The conformity index (CI) was used to describe the degree of dose-distribution conformity. The formula [22] is as follows:

where TVRI is the target volume receiving the prescribed dose, TV is the target volume, and VRI is the volume encompassed by the prescribed isodose. The CI ranges from 0 to 1.

The gradient index (R50), defined as the ratio of the 50% prescription isodose volume to the GTV, was used to assess the steepness of the dose gradient for each treatment approach.

Statistical analysis

Side effects and adverse events were continuously monitored. For statistical comparisons between the above dose metrics and those outlined in the RTOG 0915 protocol, Friedman tests were performed, followed by post-hoc Wilcoxon t-test signed-rank tests if significance was reached. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 26.0, IBM Corp. NY, USA).

Results

The characteristics and dosimetric plan quality results for all patients are summarised in Table 1. The GTV volume ranged from 0.79 to 45.16 cm3, with a mean of 12.23 cm3.

Table 1

Patient and tumour characteristics

Safety and efficacy of ISBT

All 21 patients tolerated the procedure well, with no intra- or perioperative complications. Specifically, no grade II or higher complications such as bronchopleural fistula, pneumothorax, haemoptysis, or chest wall necrosis were detected on physical examination or follow-up CT. Only two patients developed minor subcutaneous haemorrhage, and another two developed minor subcutaneous emphysema.

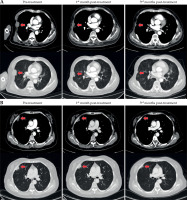

The median follow-up was 7.48 months (3-11 months). Among the patients, six (28.57%) achieved a CR, ten (47.62%) achieved a PR, four (19.05%) had SD, and one (4.76%) experienced PD. CT scans taken at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months after treatment for two representative patients are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1

Patterns of radiologic response to interstitial brachytherapy CT before treatment, at 1 month, and at 3 months after treatment for two patients

Of the 11 patients who reported pretreatment pain (one severe, six moderate, and four mild), the pain relief rate was 87.5% (9/11). One patient with moderate pain and two with mild pain experienced complete pain relief after ISBT, while six patients with moderate pain reported partial pain relief.

Dosimetric comparison between ISBT and SBRT

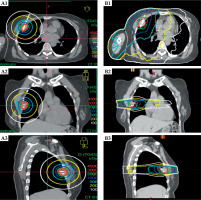

The dosimetric and plan quality results for all patients are summarised in Table 2. The Dmean to the GTV was significantly higher with ISBT compared with SBRT (p < 0.001). The CI, R50, V30Gy, and V5Gy also differed, with SBRT generally exhibiting higher values (Figure 2).

Fig. 2

Dose distributions of interstitial brachytherapy and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for treated lesions in different cross-sections. A) interstitial brachytherapy; B) SBRT

Table 2

Dosimetric and plan quality results for all patients

[i] SBRT – stereotactic body radiotherapy, GTV – gross tumour volume, D99 – dose received by 99% of the target volume, Dmean – mean dose received by the target volume, V100/V90 (%) – percentage volume of the tumour target receiving 100% and 90% of the prescription dose, R50 – gradient index, defined as the ratio of the 50% prescription isodose line to PTV volume, V30Gy/V15Gy (cm3) – volume received by 30 Gy and 15 Gy, Dmax – maximum dose, D0.35cm3, D1cm3, D1.2cm3, D4cm3, D5cm3, D10cm3, D15cm3 – dose received by 0.35 cm3, 1 cm3, 1.2 cm3, 4 cm3, 5 cm3, 10 cm3, 15 cm3 of volume respectively; V5Gy, V10Gy, V20Gy (%) – percentage volume of the lung receiving 5 Gy, 10 Gy and 20 Gy

Dose constraints were achieved for all OARs except for the ribs and chest wall. The ribs and chest wall maximum dose of 1 cm3 (D1cm3) limited to 22 Gy was exceeded by 0.16 and 0.09 Gy in two ISBT plans, and by 2.42, 2.02, 2.73, 3.81, and 4.01 Gy in five SBRT plans. The maximum rib and chest wall dose (Dmax) was exceeded in one ISBT plan by 2.13 Gy, and in four SBRT plans by 1.01, 1.41, 1.42, and 1.63 Gy. The overall mean doses to the ribs and chest wall (D1cm3 and Dmax) remained within the RTOG constraints. Statistically, all dose-volume histogram (DVH) metrics related to normal tissue showed differences between the treatment methods, except for Dmax and D15cm3 of the heart and Dmax of the trachea.

Discussion

The treatment of pleural and chest wall tumours has long been challenging owing to their anatomical proximity to vital organs (e.g. lungs, pleura, and ribs) and their tendency to invade neural structures (e.g. intercostal nerves and mural pleura), leading to severe pain and dysfunction. In this study, we focused on CT-guided 192Ir HDR ISBT, systematically evaluating its safety and efficacy in this type of tumour, aiming to provide a new therapeutic strategy for clinical use.

Anatomically, ISBT is safe in complex thoracic regions. Chan et al. [23] reported fewer rib and chest wall dose exceedances with CT-guided high-dose-rate brachytherapy compared with SBRT (2 vs. 5 cases), a pattern similarly observed in our cohort. This advantage arises from the direct implantation of the 192Ir source, which avoids high-dose radiation passing through bony structures and thereby reduces the risk of osteonecrosis, as highlighted by the RTOG 0915 criteria for chest wall metastases.

In terms of clinical efficacy, we achieved encouraging results: the objective remission rate (CR + PR) reached 76.19%, the pain relief rate was 87.5%, and no serious grade II complications were observed. Notably, among the 11 patients with pre-treatment pain, 3 (27.27%) achieved complete remission, and 6 (54.55%) achieved partial remission. NRS scores decreased from 4-9 (median, 6; indicating moderate to severe pain) before treatment to 0-5 (median, 3; mild pain) at 1 month after treatment. These findings suggest that ISBT offers rapid and sustained efficacy in managing tumour-associated neuropathic pain. The mechanism of action may involve the single high-dose radiation (30 Gy) provided by ISBT, including tumour regression to alleviate compression, inhibition of inflammatory factor release, and direct damage to nerve fibres. ISBT may be a therapeutic option for intractable chest wall pain, especially in patients who are intolerant of or resistant to opioids.

From a dosimetric perspective, ISBT offers unique advantages by delivering highly conformal high doses to the GTV while significantly reducing exposure to surrounding normal tissues, embodying the “precision strike” concept. This is exemplified by our finding, which shows a significantly higher GTV Dmean with ISBT compared with SBRT, a critical factor in tumour control. Such a dose distribution is particularly suitable for pleural and chest wall tumours, where conventional external radiotherapy often fails to balance target coverage and organ protection, leading to underdosing or normal tissue overdose. ISBT overcomes this through flexible needle trajectories and three-dimensional optimisation, as corroborated by Pang et al. [24], whose study on peripheral lung cancer reported a 100% objective response at 6 months, highlighting concentrated tumour dosing with sharp dose gradients (R50: 2.9 vs. SBRT: 4.3) to minimise normal tissue exposure. This precision establishes ISBT as a superior treatment option for anatomically complex thoracic tumours.

Surgical treatment of chest wall tumours often results in structural defects and is indicated only for limited lesions. Cryoablation, although effective for pain management, carries a risk of chest wall necrosis in post-radiotherapy tissues [25, 26]. Compared with ablative techniques such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA), CT-guided 192Ir HDR ISBT offers distinct clinical advantages in terms of dose conformity and deep tumour penetration. RFA and MWA are highly effective for treating superficial lesions by generating thermal energy to induce tumour necrosis; however, these techniques face limitations when treating lesions adjacent to vital structures (e.g. the lung or spinal cord) due to potential heat diffusion and the difficulty in achieving precise dose shaping [27, 28]. A recent case report [29] demonstrated that salvage HDR brachyablation via CT-guided catheter implantation could safely manage large recurrent tumours (up to 5 cm) with minimal complications, supporting the clinical utility of ISBT in anatomically complex sites. ISBT enables direct tumour targeting via interstitial needle implantation, allowing high-dose irradiation to the GTV with sharp dose gradients that spare surrounding normal tissues. This advantage is corroborated by our dosimetric analysis, which showed lower doses to OARs compared with virtual SBRT. This precision is particularly valuable for pleural and chest wall tumours located near critical structures, where thermal ablation may carry higher risks of complications, such as pneumothorax or neural injury. While RFA and MWA are suitable for small, superficial tumours, ISBT appears to be the preferred option for larger lesions or those in anatomically complex locations, providing a balance between tumour control and normal tissue preservation. In this study, seven patients (28%) had received prior radiotherapy for the primary lesion and did not develop chest wall necrosis or bronchopleural fistulae after ISBT. This suggests that ISBT may be better tolerated for recurrent tumours after radiotherapy. This could be attributed to the radiation source acting directly on the tumour core, thereby minimising secondary damage to surrounding fibrotic tissue.

This study primarily examines HDR ISBT, although low-dose-rate brachytherapy (LDR BT) remains a viable alternative involving the prolonged implantation of radioactive sources (over several days to weeks) to deliver low-dose irradiation. While LDR BT has demonstrated efficacy in treating slow-growing tumours, it necessitates extended hospitalisation and is associated with a higher risk of source displacement and infection [30, 31]. In contrast, HDR ISBT offers several advantages, including outpatient delivery, reduced procedural discomfort, and sharper dose gradients that spare adjacent organs, which are particularly important for thoracic tumours situated near vital structures such as the spinal cord. Additionally, HDR ISBT allows dynamic dose optimisation through real-time adjustment of source dwell times and implantation trajectories, enhancing target coverage while minimising radiation exposure to healthcare providers via remote afterloading systems. This contrasts sharply with LDR BT’s manual implantation approach, which significantly increases occupational radiation risk. The single-fraction 30 Gy regimen utilized in this study is consistent with HDR protocols that aim to balance tumour control and normal tissue preservation, whereas LDR typically involves fractionated dosing that may be less suitable for patients with poor performance status. Given the limited median survival of patients with thoracic wall malignancies and the clinical need for rapid symptom relief, single-fraction HDR ISBT was prioritised to reduce treatment burden. Although LDR BT remains effective in specific contexts, it may be less appropriate for patients with limited life expectancy or comorbidities precluding prolonged implantation.

This study provides preliminary evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of ISBT; however, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the small sample size and single-centre, retrospective design limit generalisability. The findings in this cohort of 21 patients require validation in multicentre, prospective studies. In particular, the relatively short follow-up period (median: 7.48 months) limits assessment of late toxicities (e.g. rib fractures, skin ulceration) and long-term tumour control. Extended follow-up is essential in future studies, as short-term data may not capture the full spectrum of delayed complications or recurrence. Second, the lack of a quantitative quality of life assessment is a key limitation; pain was evaluated solely using the NRS, without incorporating standardised instruments such as the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire – Core 30 (QLQ-C30), which would have better reflected treatment-related impacts on patients’ sleep and mobility.

Conclusions

In this study, we systematically evaluated the safety and efficacy of CT-guided 192Ir high-dose-rate ISBT for pleural and chest wall tumours, offering a potential treatment option for refractory disease. With precise dose distribution and image-guided, minimally invasive implantation techniques, ISBT provides notable advantages in target coverage, pain relief, and preservation of normal tissues, particularly in patients unsuitable for surgery or EBRT. Importantly, these findings represent preliminary evidence, and the assessment of long-term outcomes, including late toxicities and durable tumour control, requires further validation through extended follow-up studies.