CASE REPORT

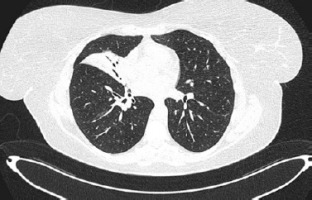

A 45-year-old female with hypothyroidism and impaired glucose tolerance was admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) because of fever, productive cough, sore throat and mucosal changes: oral erosions and conjunctivitis. Two days prior to the visit to the ED the patient was diagnosed with atypical pneumonia by a general practitioner; lately her daughter had Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. The patient had been treated with clarithromycin 500 mg/12 h for 2 days. She reported that she had been using ibuprofen for 5 days prior to antibiotic therapy. She had never noticed any adverse reactions to ibuprofen or any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs before. During the visit to the ED she was consulted by an infectious disease specialist, who confirmed mycoplasma infection with mucosal involvement. Chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) revealed consolidations mainly in the middle lobe, with surrounding ground glass opacities. Continuation of antibiotic therapy and moisturizing eye drops were recommended. Six days later the patient was readmitted to the ED due to progression of mucosal changes: hemorrhagic crusting of the lips and vast erosions of the oral cavity – vestibule, tongue and palate (Figure 1). Moreover, severe conjunctivitis (Figure 2) accompanied by purulent secretion, and a cough with green sputum. Additionally, singular (below 1% of the skin body surface area) flat and red lesions (about 0.5 cm in diameter) were observed on the left thigh, right scapula, and left breast with negative Nikolsky’s sign. On physical examination, auscultation revealed crackles over the middle lobe of the right lung. Chest HRCT showed atelectasis (Figure 3) of the middle lobe and evolution of ground glass opacities in both lungs. Following a dermatological consultation, the patient was admitted to the Clinical Department of Pulmonology, Allergology and Internal Medicine with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia with a suspicion of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). On admission she was in stable medical condition, with blood pressure of 140/94 mm Hg, oxygen saturation on atmospheric air (SpO2) of 94%, regular heart rate of 96/min. Laboratory blood tests revealed high C-reactive protein (CRP) – 100 mg/l and hypokalemia. Because hypersensitivity reaction to clarithromycin could not be excluded it was replaced by doxycycline. The patient was consulted with a dermatologist, ophthalmologist and laryngologist. According to recommendations, a corticosteroid intravenous therapy was started at a dose of 60 mg methylprednisolone for 4 days, followed by gradual tapering of the dose. Ocular ofloxacin and dexamethasone were started as well as moisturizing eye drops. Moisturizing of the lips was recommended, and betamethasone with fusidic acid ointment was prescribed for application to the lips once daily. The patient was instructed to rinse the oral cavity 2–3 times daily with a formula containing nystatin, vitamin B12, borax, and anaesthesin. During hospitalization, a single intravenous infusion of 10 g immunoglobulins was administered. Positive anti-Mycoplasma pneumoniae antibodies (IgM and IgG) confirmed Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, therefore doxycycline antibiotic therapy was continued. Following the treatment, inflammatory markers continued to decrease, and gradual improvement in mucosal lesions was observed, including the reduction of erosions in the oral cavity. The patient was discharged with the recommendation for continuing the oral steroid therapy with methylprednisolone in a gradually tapered dose over following weeks along with fluconazole and local treatment. At the follow-up visit, the patient reported significant improvement in both skin and mucosal lesions. No lesions were observed in the oral cavity or on the vermilion border of the lips, though mild tingling sensation around the lips persisted. The patient also noted persistent dryness at the outer corners of her eyes but no purulent lesions. Additionally, she reported insomnia and excessive sweating, likely related to the prolonged corticosteroid therapy. Laboratory findings showed neutrophilic leukocytosis with negative CRP, likely a side effect of systemic steroid therapy. Chest HRCT showed significant regression of inflammatory changes, with only residual postinflammatory changes in the middle lobe of the right lung. The patient’s condition has improved markedly and further reduction of the methylprednisolone dose was ordered.

DISCUSSION

Identifying the culprit of SJS in patients may be challenging. This case report highlights current limitations in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. From the beginning, efforts were made to establish the cause of the mucosal and skin reactions. Two key suspects were a hypersensitivity reaction to clarithromycin, and reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption (RIME) due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Macrolides, antimicrobial agents that inhibit bacterial protein synthesis by reversibly binding to the 23S ribosomal RNA in the 50S prokaryotic ribosomal subunit, are characterized by a lactone ring varying from 12 to 18 atoms. Hypersensitivity reactions to macrolides are rare, with an incidence of 0.4–3% [1]. Macrolides can cause both allergic and nonallergic adverse effects, i.e. prolongation of QT interval and gastrointestinal symptoms. Immediate allergic reactions include urticaria, anaphylaxis and angioedema. Non-immediate reactions may consist of maculopapular exanthema, fixed drug eruption, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, SJS, toxic epidermal necrolysis. In this case, first lesions appeared early – only 2 days after the initiation of clarithromycin use. A typical time interval between the start of drug intake and first occurrence of reactions for SJS is between day 4 and day 28 [2]. Because there was a strong suspicion that the patient experienced a severe reaction caused by clarithromycin, graded challenge was contraindicated. It was decided not to carry out skin tests with clarithromycin due to the fact that patch tests do not appear to have high sensitivity in SJS diagnosis [3]. Positive patch tests would confirm drug hypersensitivity. On the other hand, negative test results would not exclude drug allergy thus drug provocation would still be needed. Although there were individual reports of cross reactivity, it would appear that macrolide hypersensitivity is unlikely to be a class hypersensitivity [4]. This is why the patient was instructed to avoid clarithromycin only in the future. The other and more possible cause of the patient’s symptoms was RIME. RIME is a broad term for a reaction, which can be caused by viruses and bacteria, i.e. Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Influenza B virus or enterovirus [5]. It is a severe mucocutaneous reaction that occurs mainly in children and adolescents, following an infection (most commonly Mycoplasma pneumoniae). It consists of mucositis (hemorrhagic crusting of the lips, purulent conjunctivitis and less commonly urogenital lesions), usually with low severity of cutaneous involvement. RIME was coined in order to distinguish patients with infectious cause of illness from those with drug-related symptoms. Pathogenesis of RIME has not been known yet. The most popular theory includes skin damage from immune complex deposition, involving molecular mimicry between Mycoplasma pneumoniae adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens. The patient’s symptoms were mostly mucosal. During laboratory testing, Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection was confirmed, moreover prior to the patient’s disease, her daughter had developed Mycoplasma infection. The lack of skin biopsy in this case was not a diagnostic limitation. RIME and SJS exhibit similar and overlapping histopathological characteristics, including apoptotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular dermal infiltrates. Possibility of histopathologic distinction between these syndromes remains a controversial topic [6]. Compared with the SJS, RIME has a milder course, and in general good prognosis.

CONCLUSIONS

Treatment with the changed antibiotic, systemic and local corticosteroid therapy supported by intravenous immunoglobulin would be effective both in SJS caused by clarithromycin allergy, and in RIME. The most likely cause of mucosal and cutaneous changes in the patient described was determined to be Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. The case was unclear because of the coincidence of drug administration and symptoms. As drug provocation tests in such severe manifestations are contraindicated, there is a need for advancement in the field of in vitro testing. Given the rising rates of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonitis cases, problems of overlapping symptoms of possible delayed hypersensitivity reactions to macrolides and mucosal manifestations of infections can be more pronounced in the future. In addition, it can lead to overdiagnosis of certain drug hypersensitivity reactions. Because of that, establishment of a national registry for suspected Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis cases would facilitate data collection and research efforts, enabling the generation of local evidence that can inform guideline development.