INTRODUCTION

The diagnostic and therapeutic approach to asthma exacerbations in children has been thoroughly outlined in the STAN4T guidelines [1]. In contrast, the corresponding section addressing adult patients was presented in a more abbreviated form, as both the authors and consultants assumed the issue to be well understood, the recognition straightforward, and the management self-evident. Nevertheless, feedback from practising physicians – including readers of the aforementioned guidelines – indicates that the identification of asthma exacerbations in adults is frequently inaccurate, particularly among general practitioners, and that management is often inappropriate. Surprisingly, three recurring errors predominate:

Antibiotic treatment;

Treatment involving the addition of high-dose ciclesonide to an existing, ineffective regimen – previously unused by the patient;

Use of nebulised corticosteroids (CS) in adults in home settings.

In light of the above, this paper focuses on this issue.

DEFINITION OF ASTHMA EXACERBATION

Asthma exacerbation is defined as a progressive increase in symptoms including shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, and chest tightness, along with a deterioration of ventilation parameters (PEF, FEV1), necessitating a change in treatment.

The definition does not address the underlying cause of the exacerbation but accurately reflects the clinical course of the disease. Symptoms arise suddenly, tend to progress, and do not resolve spontaneously. They may be accompanied by increased sputum production and dyspnoea. A characteristic feature is a drop in oxygen saturation, which may occur even at rest.

Severe asthma exacerbation is defined by the patient’s clinical condition, characterised by severe asthma symptoms from the onset or no improvement despite treatment for more than 48 h [1].

Exacerbations typically result from exposure to environmental factors (such as viral respiratory infections, allergens, or inhaled irritants) and/or non-adherence to prescribed pharmacological regimens. However, asthma exacerbations can sometimes occur without an apparent cause. Nevertheless, exacerbations are far more often triggered by combined exposure to viruses and allergens. Poor adherence, non-compliance with therapeutic recommendations, and inadequate treatment are frequently contributing factors [2–6]. Exacerbations, including severe ones, may also occur in patients with mild or moderate asthma – in other words, in virtually any patient. In many cases, the aetiology of an exacerbation is viral; in such instances, the exacerbation is usually preceded by rhinorrhoea, and sometimes by pharyngitis [7, 8].

CAUSES OF ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

Inadequate treatment.

Non-adherence to therapeutic recommendations.

Incorrect inhaler technique.

Viral infections of the upper and lower respiratory tract.

Allergen exposure in sensitised patients.

Food exposure in patients with asthma and food allergy.

Air pollution.

Tobacco smoke exposure (both active and passive).

Use of medications that may worsen asthma symptoms (e.g., β-blockers or aspirin) [9, 10].

TYPICAL CLINICAL SYMPTOMS OF EXACERBATION

Sudden deterioration of asthma symptoms persisting for more than 24 h.

Pronounced dyspnoea.

Cough.

Wheezing.

Tachypnoe.

Sudden onset of reduced exercise tolerance.

Increased volume of expectorated secretions.

Drop in peak expiratory flow (PEF) or forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) greater than 20% compared to the previous result for 2 consecutive days, or a 20% decrease relative to the patient’s personal best.

Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is uncommon.

Similarly, leukocytosis and fever are not typical features of an exacerbation.

In the clinical examination, prominent wheezing and/or rhonchi predominate, and the expiratory phase is prolonged. Clinical examination is rarely normal. If it is, one should consider whether the patient may have another serious underlying medical condition.

MILD VERSUS SEVERE ASTHMA EXACERBATION

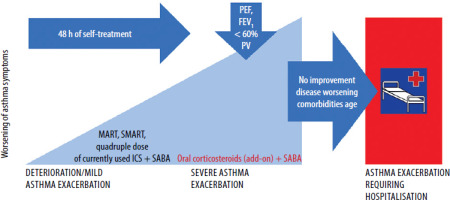

A mild exacerbation is typically an episodic and largely reversible worsening of asthma symptoms. If clinical symptoms persist despite treatment for more than 48 h, the exacerbation should be classified as severe. Similarly, a severe exacerbation is defined as a condition in which FEV1 or PEF falls below 60% of the patient’s personal best [1]. Unfortunately, this definition is primarily applicable in clinical research and has limited practical value. Therefore, I propose that if pronounced asthma symptoms do not resolve within 48 h, oral corticosteroids (OCS) therapy should be considered unequivocally indicated (Figure 1). No alternative treatment exists.

Figure 1

Clinical and therapeutic algorithm of asthma exacerbation

PEF – peak expiratory flow, FEV1 – forced expiratory volume in 1 s, PV – predicted value, ICS – inhaled corticosteroids, MART – Maintenance and Reliever Therapy, SMART – Single Maintenance and Reliever Therapy, SABA – short-acting b-agonists.

Because severe exacerbations often evolve over several days before the patient seeks medical care, there has been ongoing debate about whether to distinguish between mild and severe forms – or whether every symptomatic exacerbation observed in a clinical setting should be treated as severe. This is particularly relevant for patients managed under LPiD, Single Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (SMART), or Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (MART) protocols. Interestingly, individuals treated with these regimens tend to experience asthma exacerbations less frequently than others [11–15].

Differential diagnosis of asthma exacerbations is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Differential diagnosis of asthma exacerbation

MANAGEMENT OF ASTHMA EXACERBATIONS

Essential steps include:

Assessing the severity of the exacerbation and potential risk of death;

Determining the time of symptom onset, their nature, and any treatment already initiated;

Evaluating the patient’s vital signs;

Assessing the nature, progression, and level of control of any comorbid conditions;

Measuring oxygen saturation and, if possible, PEF. Treatment of asthma exacerbation

Increasing the frequency of as-needed medication (e.g., salbutamol, formoterol);

Temporarily intensifying baseline asthma therapy (primarily by increasing controller medication doses up to fourfold) [16–20]. This approach is suitable only for mild exacerbations and should be used for a short duration.

Severe asthma exacerbations are treated with OCS (methylprednisolone at 32 mg for 5 days) [1]. This treatment is effective, patient-friendly, simple, and well tolerated. If improvement occurs, the CS dose may be discontinued without the need for gradual tapering.

Some patients experiencing severe asthma exacerbations may require treatment in the emergency department or hospital. The indications for hospitalisation are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Risk factors for hospitalisation and death due to asthma

It is important to note that the current STAN4T guidelines in Poland recommend treating exacerbations exclusively with short-term administration of OCS [1]. No other Polish recommendations exist in this area. Specifically, the following are not recommended:

Administering additional doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) beyond the fourfold increase of the patient’s current CS regimen. This strategy is supported by low-quality evidence (Grade D);

Using ICS nebulisation in adults, as this is impractical and minimally effective;

Administering parenteral CS in conscious patients breathing spontaneously;

Introducing medications other than those listed above.

Increasing the dose of an already prescribed controller medication (ICS or ICS/long-acting β-agonists (LABA) in a single inhaler) up to fourfold may have limited effectiveness and is rarely well accepted by patients. Nonetheless, this approach offers certain advantages:

The patient already possesses the medication, is familiar with the inhaler, and likely knows how to use it;

It does not require a medical visit to initiate exacerbation treatment;

It can be initiated at the onset of the first exacerbation symptoms, allowing the patient to take advantage of a 24-hour window in which the exacerbation may be prevented without the need to introduce new medications.

Hence, in many countries, the MART and SMART treatment approaches have gained popularity. These involve both maintenance and reliever therapy administered from the same inhaler containing an ICS and formoterol (F). This approach consists of using fixed doses, usually twice daily, with escalation of therapy in response to worsening asthma control. GINA guidelines recommend this strategy as the first-line option, while the treatment pathway involving ICS + LABA with as-needed short-acting β agonists (SABA) is considered an alternative. In Poland, however, active use of maintenance-and-reliever therapy is relatively uncommon, mainly due to insufficient physician education and the fact that transferring part of the responsibility for treatment to patients is poorly accepted by both sides of the therapeutic process.

Nevertheless, self-escalation of ICS/F therapy is recognised by GINA as a means of preventing/managing asthma exacerbations before the patient seeks medical attention. Numerous observational studies, along with the author’s own clinical experience, indicate that this approach is effective and well accepted by patients – but only when physicians devote sufficient time to explaining its use and consistently reinforce education at every visit. However, this approach also has two drawbacks that have never been demonstrated in clinical trials, as no one has undertaken the risk and cost of such studies:

A patient who escalates asthma therapy may overlook the fact that they are already experiencing a severe exacerbation requiring OCS treatment;

Patients tend to escalate and de-escalate therapy with equal ease, and over time may end up taking only half the recommended dose (for example, once daily).

Asthma treatment in Poland has its own particular features. One such practice is the addition of extra doses of a different ICS – not previously used by the patient – during an exacerbation. Quite frequently, though not exclusively, ciclesonide delivered via pMDI is used for this purpose. There is very limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of this approach [21]. It carries the lowest level of scientific evidence according to GINA (Grade D). In general, several factors suggest the limited effectiveness of this approach:

The time between disease deterioration and initiation of treatment typically indicates that the patient is already experiencing a severe exacerbation;

Adding another inhaler to the current regimen tends to reduce adherence to therapeutic recommendations;

A large number of inhaled doses (e.g., 2 standard daily doses plus 8 additional doses for the exacerbation) may lead − even with a relatively safe ICS such as ciclesonide − to adverse effects in the throat and larynx, often related to the drug carrier;

It is inconvenient and impractical;

In the case of a severe exacerbation, the inflammatory process always involves the bronchial interstitium and the perivascular space. The pathway for corticosteroids delivered via the bronchi is significantly longer than when the anti-inflammatory drug is administered orally and reaches the site through the bloodstream.

As is clearly evident, oral administration of corticosteroids is a significantly better option for treating asthma exacerbations than inhaled delivery – especially when high doses are given over a short period.

INSTEAD OF A SUMMARY

WHAT TO DO

Avoid exacerbations by:

Accurately assessing asthma severity;

Individualising treatment in line with STAN4T guidelines;

Using appropriate medications in well-matched doses and inhalers;

Evaluating adherence to therapy and inhaler acceptance;

Administering vaccinations against influenza, pneumococci, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

Prepare and provide the patient with a written action plan for exacerbation management.

Recognise exacerbations and treating them with OCS as recommended by STAN4T.

Analyse the causes of exacerbation and implement effective prevention strategies.

Reclassify the patient as having poorly controlled asthma following an exacerbation.

WHAT NOT TO DO

Do not ignore repeated asthma exacerbations, dismissing them as “just a cold” or “bronchitis.”

Avoid a “one-size-fits-all” approach to asthma treatment.

Strongly avoid the use of nebulised CS in the treatment of exacerbations in adult patients.

Do not administer a high number of ICS doses during exacerbation treatment.

Do not prescribe antibiotics for asthma exacerbations unless there is clear evidence of a bacterial cause.