INTRODUCTION

Migraine without aura is the most common type of the condition, whereas migraine with aura is substantially less common. According to the literature, previously used terms for migraine with aura are classic or classical migraine, ophthalmic, hemiparesthetic, hemiplegic or aphasic migraine, migraine accompagnée and complicated migraine [1]. Rasmussen and Olesen estimated based on the sample of Danish population that lifetime prevalence of migraine with aura is 5% (8% without aura) and that the male-to-female ratio equals 1 : 2 (1 : 7 without aura). Women are significantly more likely to have attacks without aura than with, and no correlation with age has been observed in the studied age interval (25-64 years). There were no such findings for the population of men studied [2].

The migraine aura is defined as recurrent attacks of at least one fully reversible focal neurological symptom. The 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders’ (ICHD-3) diagnostic criteria for migraine with aura include symptoms such as visual, sensory, speech and/or language, motor, brainstem and retinal disturbances [1]. Additionally, according to the current diagnostic criteria the aura symptoms should include at least three out of the six following characteristics: (1) at least one aura symptom spreads gradually over 5 minutes, (2) at least two symptoms occur in succession, (3) each individual symptom lasts 5-to-60 minutes, (4) at least one symptom is unilateral, (5) at least one symptom is positive, (6) the aura is accompanied, or followed within 60 minutes, by headache. The typical accompanying headache occurs with associated autonomic symptoms, which altogether meet the criteria for the diagnosis of migraine without aura [1].

The most common type of aura has the typical characteristic of consisting of a range of different visual, sensory and speech symptoms [1]. The visual and sensory symptoms are the most frequent manifestations during typical attacks. According to some authors, visual disturbances are the most common aura phenomenon, occurring in about 90% of subjects [3]. Other types of aura symptoms such as sensory, motor or speech disturbances rarely occur without coexisting visual disturbances. Jensen et al. [3] reported the prevalence of different types of migraine aura as 94% for visual aura, 40% for somatosensory aura, 20% for speech difficulties and 18% for motor symptoms. In their study visual aura was unilateral in 55% of cases, somatosensory aura symptoms were unilateral in 80% and motor aura was always unilateral. It is noteworthy that headache was absent in 20% of the aura attacks.

It is emphasized that aphasia (in contrast to bilateral or unilateral dysarthria) is always considered as a unilateral symptom, and it is important to pay attention to positive aura symptoms such as scintillations and pins and needles. Additionally, it is worth noting that motor symptoms may last up to 72 hours. The basis for the diagnosis of migraine, including migraine with aura and migraine aura without headache, is the exclusion of other disorders that may mimic migraine and are not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis (e.g. transient ischemic attacks [TIA], stroke, dissection of the intracerebral arteries, thrombosis of the venous sinuses or vasculitis) [1].

The visual aura is often manifested in scotoma, fortification spectrum, zigzag line or figure gradually spreading to the right or left part of visual field and forming a laterally convex shape with an angulated scintillating edge, leaving absolute or variable degrees of relative scotoma in its wake. Occasionally, scotoma without positive phenomena may occur. Interestingly, Brazilian researchers have emphasized that the most common features of the visual aura occurred before the headache with a gap of less than 30 minutes and lasting 5-to-30 minutes. The onset was usually gradual and located peripherally and unilaterally, with shimmering. In their study, the visual aura symptoms most often described were small bright dots and zigzag lines, whereas blurred vision was not typical [4]. Next in frequency of occurrence are sensory disturbances, often manifested in the form of pins and needles spreading slowly from the point of origin and affecting a greater or smaller part of one side of the body. A feeling of numbness may occur in its wake, although in some cases numbness may be the only sensory symptom. Speech disturbances, such as aphasia, occur less frequently and very often are difficult to categorize. When the aura includes motor weakness, the disorder should be diagnosed as a hemiplegic migraine. Hemiplegic migraine can be further distinguished into the familial (FHM) or sporadic (SHM) forms [5].

The currently available data strongly suggests that the pathophysiology of migraine aura is mainly related to cortical spreading depression (CSD). CSD is the phenomenon of a slowly propagating wave of depolarization across neuronal and gial cells and it is temporally related to the aura symptoms. The underlying mechanism of CSD is connected to the accumulation of potassium ions in the extracellular matter, which starts the depolarization. Cortical activity is later inhibited during an ongoing aura phase for up to 30 minutes. It is believed that CSD starts at the occipital cortex and propagates to the anterior areas. This mechanism could explain the typical sequence of the occurrence of aura symptoms, yet visual disturbances are usually the first to appear [6, 7]. It is important to mention that genetic factors play a major role in the pathogenesis of migraine aura. There are a small number of monogenetic mutations responsible for FHM, but also overall genetic predispositions may modify CSD response [1, 6, 7].

Different aura symptoms may determine a different diagnostic approach and management. The aim of the study was to assess the characteristics of migraine attacks with aura in a sample of Polish patients. The characteristics assessed included type and severity of aura, as well as the risk of migraine chronification.

METHODS

The study group included 111 consecutive patients from a Headache Outpatient Clinic diagnosed with migraine (with and without aura). The study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Medical University of Warsaw (AKBE/224/2022). Oral informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Data was gathered between the end of January 2020 and the beginning of December 2020. A full neurological examination of all the patients was conducted by a neurologist. All the patients were diagnosed with migraine according to the ICHD-3 of the International Headache Society (IHS) [1].

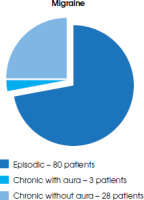

There were 97 women (87.4%) and 14 men (12.6%) in the study group. Patients’ mean age was 37.86 ± 11.80 years old (range 16-73 years). Eighty patients (72%) were diagnosed with episodic migraine (78 female and 12 males; mean age 37.82 ± 11.73). Thirty-one patients (28%) were diagnosed with chronic migraine (29 female and 2 males; mean age 38.33 ± 11.93).

The study included 83 patients (75%) diagnosed with migraine without aura and 28 patients with migraine with aura (25%); mean age was 34.89 ± 12.25 years old (range 17-67 years).

RESULTS

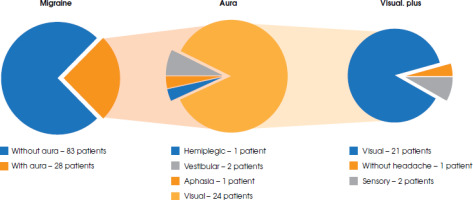

Out of all 111 migraine patients included in the study, a group of 28 patients with migraine with aura were selected and further analysed. The group consisted of 22 female and 6 male patients. Further demographic and epidemiological data is shown in the Table 1. Figure I graphically presents the distribution of different aura types among all the patients with specified additional characteristics of visual aura. Twenty-five patients were diagnosed with episodic migraine, whereas 3 were diagnosed with chronic migraine. Figure II shows the distribution of episodic migraine and chronic migraine (with and without aura) among the patients.

Table 1

Epidemiological and demographic data of patients included in the study

Figure I

Distribution of different aura types among all the patients, with specified additional characteristics of visual aura

Figure II

Distribution of episodic migraine and chronic migraine (with and without aura) in the study population

In this group, 13 patients (12% of all migraine patients and 46% of migraine with aura patients) suffered from both types of migraine attack. Out of this subgroup, 3 patients suffered more often due to having attacks of migraine with aura (the visual type).

In the group of migraine with aura, distinct types of auras were diagnosed:

visual – 24 (86%) patients (1 without headache, 2 with numbness and paraesthesia and speech disturbances),

aphasia – 1 patient,

vestibular – 2 (7%) patients,

hemiplegic – 1 (3.5%) (FHM diagnosed).

The duration of the aura varied, lasting between 15-to- 60 minutes. All patients with visual aura reported a mean duration of visual impairment of approximately 20 minutes. Patients who additionally experienced numbness and paraesthesia did not report an extended duration of overall aura for more than 60 minutes. One patient diagnosed with FHM sequentially developed symptoms in the following order: scotoma, numbness increasing from the distal parts of the limb, and increasing paresis. The overall duration time of all the symptoms did not exceed 60 minutes.

All the patients diagnosed with visual aura reported scotoma. Additionally, 5 of them reported partial anopsia, 2 patients reported a fortification spectrum, and 1 patient reported a zig-zag line.

Two women were diagnosed with menstrual migraine. One of them had migraine attacks with a visual aura exclusively, while the other suffered from attacks with and without aura (the attacks without aura were four times more frequent than those with aura).

The frequency of migraine aura attacks of all the patients varied from 1 per week to 1 every three months, with an average rate of 1 attack per month.

Only 3 chronic migraine patients reported a significant negative effect on the quality of life (EQ-5D-5L). Only one patient, diagnosed with FHM, reported that his attacks of migraine with aura were troublesome for him. In the case of this patient attacks were rare, occurring with a frequency of less than once every 3 months, and disappeared completely after treatment with valproate. However, the overall data regarding specific anti-migraine treatment was not collected and thus was not further analysed.

No correlation was noted between the reported parameters, but the study group is too small, and the parameters are convergent. Table 2 shows the summary of the aura-related data collected.

Table 2

Summary of aura features

DISCUSSION

Our study confirms that the most typical and the most frequent migraine aura attacks have visual symptoms. Occasionally, impairment in sensation or speech can be observed in typical aura attacks. In our study, vestibular and hemiplegic migraine were rare manifestations of aura. In fact, around 15%-to-30% of worldwide migraineurs experience aura, whereas visual aura is the most common type of aura, occurring in over 90% of patients, which is consistent with our study: 25% and 86%, respectively [6].

Other authors characterised aura types and migraine headache with accompanying symptoms in 30 children aged 8-17 years. Similarly, visual aura was also the most frequent type of aura in children (20 out of 30 patients). Other symptoms reported in the study, starting from the most frequent, included somatosensory aura, aphasic aura, and brainstem aura [8].

Cologno et al. [9] investigated the evolution of migraine with aura over time in a group of 81 patients consecutively referred to one headache centre. Their study proved a favourable evolution of migraine with aura during the observation of a minimum 10 years. As the patient selection method was similar to our study, further observation of our patients could provide important data.

A group of 362 Danish patients diagnosed with non- hemiplegic familial migraine with aura was described by Eriksen et al. [10]. The clinical characteristics included typical visual aura attacks and aura without headache. The authors concluded that there seems to be a correlation between more severe symptoms and familial aggregation. We have not checked this hypothesis, but it seems interesting and requires confirmation in the further observation of our study group.

Another problem is the occurrence of headache during an ongoing aura phase. None of our patients reported such a symptom, whereas some authors confirmed that headache can occur during aura phase in most migraine attacks [11]. Other migraine symptoms such as nausea, photophobia and phonophobia were also frequently reported during aura. An acceptable duration for most aura symptoms is one hour, but motor symptoms, which are rare, often last longer. It is important to note that a long duration (more than one hour) of what may or may not be an aura phase, late onset of aura, or a dramatic increase in aura attacks should be explored further in each case due to the elevated risk of a symptomatic manifestation of other diseases [6, 12]. If other potential causes are excluded, such aura should be classified as a prolonged aura and it may require an additional therapeutic approach. There is a lack of high-quality evidence for the treatment of prolonged aura; however, the data available provide a variety of therapeutic options. The current guidelines issued by Polish headache experts suggest the treatment of prolonged aura symptoms with valproic acid [13]. Moreover, a small number of studies report on the efficacy of several other drugs such as ketamine, verapamil, magnesium, acetazolamide and triptans. One additional option that could provide aura relief is a greater occipital nerve block procedure [14].

It is also worth mentioning that migraine attacks with aura demand a different approach to acute treatment compared to those without it. Triptans are contraindicated during the ongoing aura phase and should be administered only after the onset of headache and full relief from aura symptoms [13, 14]. There is no such restriction for other acute anti-migraine drugs [13]. Furthermore, in a recent study ubrogepant proved to be an effective and safe therapeutic option of abortive treatment, even during the prodromal phase of a migraine attack, regardless of the presence or otherwise of aura [15].

In our study only 10.7% of migraine with aura patients developed the chronic type of migraine. In comparison, 33.7% of migraine without aura patients were diagnosed with this. Some authors confirm that chronic migraine more often affects patients diagnosed with migraine without aura. Tsao et al. [16] investigated clinical correlates of visual symptoms in patients with migraine. Their study group consisted of 743 visual migraine patients and 1808 patients with non-aura transient visual disturbance. In their group chronic migraine was more common in migraine without aura than in the group with migraine with aura. The authors concluded that the presence of non-aura transient visual disturbance may suggest a higher migraine-related disability and is linked to higher risk of chronic migraine than typical migraine aura, but the mechanism of this correlation is unclear.

CONCLUSIONS

Although our study group was small, the results are consistent with findings among other populations. We confirm that visual disturbances are the most frequent type of aura symptoms among the group of Polish patients studied, and that the chronification of migraine is more probable in a case of migraine without aura than with aura. In some cases, the visual aura is accompanied by other symptoms of typical migraine aura such as paraesthesia and speech disturbances. Other types of aura, such as the vestibular and hemiplegic, occur very rarely. However, these data cannot be generalised to the whole Polish population as the study was performed among one Headache Centre population and the group was too small for any generalisations to be made. Further, preferably multicentre, studies are needed to assess the impact of aura symptoms on the daily lives of patients and specify other characteristics of aura. Future studies could also include treatment approaches related to aura symptoms.