INTRODUCTION

Autosomal dominant hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome (AD-HIES) is an inborn error of immunity, with an estimated incidence of approximately 1 in 100,000–1,000,000 [1], caused by a mutation in the STAT3 gene. Most cases of AD-HIES are concerned with sporadic heterozygous mutations that arise de novo [2, 3]. This syndrome occurs with equal frequency in girls and boys [2]. STAT3 protein activates and regulates the transcription of genes required for both innate and adaptive immune responses [1]. The signalling pathway involving STAT3 begins with JAK2 receptor binding. Ligands, such as cytokines and growth factors, bind to the extracellular domains of receptors, leading to JAK2 phosphorylation. The active kinase domain of JAK2 phosphorylates STAT3. STAT3 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to the promoter region of DNA. Dimerized STAT3 acts as a transcription factor and regulates cytokine production i.e. IL-6, IL-10, IL-11, IL-17, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, leukemia inhibitory factor, oncostatin M, cardiotrophin-1, cardiotrophin-like cytokines, and ciliary neurotrophic factor [4]. In AD-HIES, a significantly reduced Th17 lymphocyte response is also observed, resulting in increased susceptibility to Candida infection [1, 5, 6]. IL-17 signalling is involved in neutrophil proliferation and chemotaxis, which may partially explain recurrent staphylococcal infections [7]. The clinical presentation of AD-HIES is diverse, with a wide range of reported non-immune symptoms, indicating its multisystemic nature. The clinical presentation of AD-HIES may be subtle, potentially resulting in a delayed diagnosis. Abnormalities in the dentition, skeletal system, connective tissue, skin, and blood vessels are also observed. A characteristic immunological feature of the disease is the presence of ‘cold’ abscesses, primarily caused by Staphylococcus aureus, which are typically associated with minimal signs of inflammation caused by impaired IL-6 function [7, 8]. Other clinical symptoms comprise eczematous rashes, which may occur as early as in the neonatal period, recurrent sinusitis, and pulmonary inflammation. Levels of serum IgE can be elevated to a significant degree, often surpassing 2000 IU/ml. However, it is important to note that IgE concentration can exhibit considerable variation over time and does not always correlate with the presence or severity of clinical symptoms. In fact, elevated IgE concentrations may be observed even in the absence of evident clinical symptoms [9]. Recurrent sinopulmonary infections contribute to bronchiectasis, lung parenchymal damage, and the formation of pulmonary coelomic cysts (pneumatoceles) [7]. Musculoskeletal abnormalities include distinct facial features, such as a prominent forehead, prognathism, hypertelorism, gothic palate, craniosynostosis, and delayed loss of deciduous teeth [7]. In younger children, the dysmorphic features of the face may not be visible, but they become more prominent in adolescence. Excessive joint mobility, scoliosis, osteoporosis, and pathological fractures have also been reported [10]. AD-HIES may be associated with vascular abnormalities such as tortuosity or dilatation of the coronary arteries, vascular aneurysms, and hypertension [11].

CASE REPORT

The male infant, who was delivered spontaneously at 39 weeks of gestation, had a birth weight of 3,010 g and an Apgar score of 9/10. Following the initial month of his life, he was started on a milk-free infant formula due to the onset of eczema on his face. At the age of 3 months, he started to suffer from recurrent respiratory tract infections. At 8 months of age, the patient was diagnosed with early childhood asthma and commenced treatment with inhaled steroids, bronchodilators, and antihistamines. Subsequently, the patient developed severe bilateral acute otitis media. Laboratory tests during this period revealed decreased levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM, as well as an increased level of IgE (Table 1).

Table 1

Results of immune laboratory tests performed in our patient

At the age of 1, the patient was admitted to the hospital for surgical treatment of an abscess located around the angle of the left mandible. Microbiological analyses revealed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus MLSB and MSSA. A few months later, he was hospitalized with seborrheic erythematous dermatitis characterized by vesicles and excoriations, particularly on the forehead and cheeks. Diagnostic tests revealed elevated levels of egg white- and milk protein-specific IgE. Intravenous substitution of human immunoglobulin preparations was initiated at 18 months of age. Treatment resulted in an improvement in the patient’s immunoglobulin profile, with a notable increase in the IgG level. However, multiple fungal lesions in the oral cavity and genital regions, recurrent purulent otitis media, and persistent atopic dermatitis were still observed. Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics of changes in IgE levels.

Figure 1

The dynamics of changes in IgE levels. The date of AD-HIES diagnosis is indicated by a dashed line

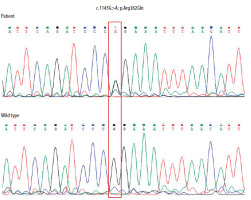

In the third year of life, the form of immunoglobulin therapy was changed from intravenous to subcutaneous. At the age of 4 years, the patient was diagnosed with autism and received ongoing psychological care. At that time, the diagnosis of AD-HIES was established. Sequencing of the STAT3 gene revealed the presence of a pathogenic substitution 1145G>A (cDNA, 1458G>A; g 58927G>A) in a heterozygous form in exon 13. This resulted in the conversion of an amino acid from arginine to glutamine (p. Arg382Gln) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Electropherogram of the fragment of the STAT3 gene’s thirteen exon in the patient showing heterozygous G to A substitution at position c.1145, resulting in an amino acid change from arginine to glutamine p. (Arg382Gln). The correct sequence of the analysed fragment of the gene in the healthy subject is shown at the bottom. The positions of these nucleotides are indicated in the red frame. The sequence fragments were displayed using Chromas Lite software

The boy started to receive prophylaxis with the antibiotic and antifungal agent, in addition to immunoglobulin substitution. At the age of seven, he developed extensive periodontal abscesses, and after surgery severe gingivitis and an abscess in the right submandibular region. During the subsequent period, the patient exhibited the presence of barley-like lesions on the eyelids, as well as small skin abscesses, extensive acne lesions, and a large peritonsillar abscess, which once again necessitated surgical intervention. Furthermore, the patient presented ligament-body flaccidity, joint overpronation, cutis laxa (skin flaccidity), a staggered foot position, hypotonia, and impaired motor coordination. Over time, the boy’s foot deformity progressed, reaching a point where surgical intervention was deemed necessary.

At present, the boy remains under the supervision of the Immunology Clinic, undergoing regular examinations to monitor his general health and immune system status.

He exhibits phenotypical characteristics of AD-HIES, including a prominent forehead, hypertelorism, prognathism, and thickened soft tissues of the ears, nose, and cheeks (Figures 3, 4).

DISCUSSION

To facilitate the diagnosis of AD-HIES, Grimbacher et al. [12] developed a scoring system that considers both clinical and laboratory features. A score of 15 or above indicates a strong suspicion of the disease. The diagnosis of AD-HIES is considered unlikely with a score of less than 10 points. The patient’s score was 36, which, according to established criteria, may indicate the presence of a mutation typical for AD-HIES. For further details, refer to Table 2.

Table 2

Scoring system with clinical and laboratory tests for individuals in kindreds with HIES from Grimbacher et al. including data of our patient (in grey windows) [12]

a The entry in the furthest-right column is assigned the maximum points allowed for each finding. bNormal < 130 IU/ml. c700/ml = 1SD, 800/ml = 2 SD above the mean value for normal individuals. dFor example, cleft palate, cleft tongue, hemivertebrae, other vertebral anomaly, etc. (see Grimbacher et al. [10]). eCompared with age- and sex-matched controls.

To the best of our knowledge, only 3 cases of AD-HIES with autism have been documented in the existing literature [13–16]. All these cases, including ours, were male and presented a number of clinical features in common with AD-HIES. However, it should be noted that only two of them had confirmed the STAT3 gene mutation. The characteristics of these 2 patients are presented in Table 3. It is relevant to note that our patient was the youngest among those described and diagnosed with the disease at an early stage.

Table 3

The comparison of clinical features of two AD-HIES patients with concomitant autism

| Parameter | Our patient | Moens et al. [14] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Male | |

| Age of diagnosis | Autism | 4 years old | 5 years old |

| AD-HIES | 4 years old | 8 years old | |

| Common symptoms | Recurrent respiratory tract infections | + | + |

| Recurrent acute otitis media | + | + | |

| Eczema | + | + | |

| Mucocutaneus candidiasis | + | + | |

| Retained teeth for extraction | + | + | |

| Facial dysmorphia | + | + | |

| Individual presentation | S. aureus abscesses Early childhood asthma Food allergy Barleys | Pleuropneumonia S. aureus sepsis Gingivitis Stomatitis Typical febrile Minor trauma fractures | |

| Laboratory abnormalities | Serum IgE level – maximum 2350 IU/ml | Serum IgE level – 180 IU/ml Low switched memory B cells High CD3(+) γδTCR(+) T cells (+/− 20% of CD3(+) cells) | |

| Mutation of the STAT3 gene | Type | Substitution: c. 1145G>A in exon 13 | Substitution: g.40485745T>G |

| Variant | Heterozygous | Heterozygous | |

| Consequence | Conversion of an amino acid from arginine to glutamine (p. Arg382Gln) | Conversion of an amino acid from histidine to proline (H332P) | |

| Description in databases | + | – | |

AD-HIES is associated with a considerable reduction in the quality of life and a high incidence of morbidity, primarily due to infections. The early diagnosis of AD-HIES, implementation of antimicrobial prophylaxis, provision of proper skin care, and administration of aggressive treatment of infections are of paramount importance in the prevention of pulmonary and skin complications [17].

Immunoglobulin replacement therapy in AD-HIES may be beneficial in certain patients with concomitant hypogammaglobulinemia, although this is not universally recommended [7]. Several trials have been conducted on immunomodulators, including cyclosporine A and interferon α, as well as on biological therapies, such as dupilumab or omalizumab. However, the efficacy of these therapies remains still unproven [18–20].

The role of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains uncertain as it has been performed in a number of patients with disparate outcomes. Nevertheless, the results of 7 cases with AD-HIES who underwent bone marrow transplantation between 1998 and 2018 are encouraging [17]. In our own experience, HSCT was performed in 1 patient with AD-HIES who presented with recurrent sinuses and periorbital abscesses. We observed very good clinical outcome. HSCT at an early age has been demonstrated to prevent the development of chronic respiratory disease, lymphoma, vascular anomalies, and osteoporosis while also promoting normal physical development in children [17, 21].

CONCLUSIONS

The presented case is distinctive because of the concurrence of autism and the favourable response to immunoglobulin substitution and antimicrobial prophylaxis. This scheme of therapy resulted in a reduction in the number of hospitalizations, improvement in the condition of the skin lesions, and a decrease in the severity of infections.