Introduction

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are a type of corticosteroids used for the past 50 years as potent anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating medications to treat various inflammatory, autoimmune, and life-threatening diseases affecting different body systems (such as dermatological, pulmonary, hematological, neurological, rheumatic, and vascular diseases). Various common and problematic (metabolic, physical, body image, mental, behavior, and mood) health problems have been described. All of them can significantly affect the health-related quality of life [1].

Steroids affect the brain’s functioning and structure by interacting with glucocorticoid receptors, potentially causing changes in the hippocampus and other brain regions. Psychiatric symptoms typically resolve when steroid therapy ceases, while some individuals may need additional therapeutic interventions. The dosage could be associated with the possibility of experiencing mental disturbances, but neither the dosage nor the duration of treatment appears to influence the severity, duration, type, and onset of mental disturbances. It is crucial to monitor patients undergoing oral corticosteroid therapy for indications of mental health issues and modify treatment accordingly [2].

Better coordination between the psychiatrist and physician can significantly enhance the quality of life for these patients. Major depressive disorder (MD) is a significant mental health issue projected to become the primary health burden globally by 2030 [3, 4]. It significantly rises during teenage years and early adulthood, with 25% of lifespan mood disorders emerging by the age of 18 and 50% by the age of 30 [5]. MD during adolescence and childhood substantially raises the likelihood of experiencing future episodes in adulthood by about fourfold [6], especially in adolescent boys and younger men aged 15–35 years [6, 7]. During childhood, the sex ratio for depression is approximately equal; however, by the final stage of adolescence, females outnumber males by about 2 to 1 [8, 9].

Material and methods

The present study adopted a cross-sectional design. The study was carried out over 6 months, from January 2023 to June 2023, at highly specialized centers in Saudi Arabia and Egypt (Al-Hussein University Hospital, National Liver Institute Hospital, Sayed Galal University Hospital, Al-Azhar University Hospital, Ain Shams University and Shaqra University). The study involved a sample of patients with various autoimmune diseases – including vasculitis, immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), sarcoidosis, autoimmune hepatitis, ulcerative colitis, iridocyclitis, Crohn’s disease, Down syndrome (DS), mixed connective tissue (CT) disease, dermatomyositis, hemolytic anemia, optic neuritis, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) – who received corticosteroids (CS) as treatment. The Faculty of Medicine’s ethical committee (Al-Azhar University-Cairo-Egypt) approved the study (IRB number 3624PR180/4/23). Subsequently, phone numbers of patients who had commenced receiving CS as treatment were obtained. We reached out to patients via their phone numbers and made arrangements for interviews at the hospital. There were 500 participants in total, consisting of 150 males and 350 females. The most common disease included in our study was primary vasculitis (20%), followed by ITP in 70 (14%), then SLE in 60(12%). The other included diseases are depicted in Table I. The majority (66%) of cases received corticosteroid doses of 20–40 mg/dl, while 34% of them received > 40 mg/dl (Table I).

Inclusion criteria included participants aged 18–60, both sexes, who provided written consent to participate in the study. Participants had to be diagnosed with an autoimmune disease within the past 6 months, have no prior history of psychiatric disorders before the autoimmune disease, and have no history of organic neurological disorders such as ICH caused by infections, brain surgery, vascular malformations, or brain tumors.

Exclusion criteria included participants aged under 18 or over 60, those who refused to participate, individuals diagnosed with autoimmune disease over 6 months ago, patients with a history of psychiatric disorder before autoimmune disease, and patients with a history of organic neurological disorders such as ICH caused by brain tumors, vascular malformations, brain surgery, or infections. Alcoholic patients were excluded from the current study based on their detailed history, taking into consideration that alcohol intake is very rare in Egypt.

All subjects were evaluated using two types of tools:

Autoimmune disease diagnosis: All patients were diagnosed with an autoimmune disease based on complete history, examination, imaging, and laboratory tests.

Psychiatric conditions were diagnosed by conducting clinical interviews with patients, complete history taking from patients, and mental state examination (MSE). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID-I): The Arabic version of the SCID-I used in this study was translated and validated as per previous research conducted by the Institute of Psychiatry, Ain Shams University [7].

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI): a self-report rating inventory consisting of 21 items that assess depressive symptoms and characteristic attitudes. The Arabic version used in this research was translated and endorsed by Prof. Magda Al-Shahry.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 24. The Mann-Whitney U test (MW) was performed to compare two means (for abnormally distributed data). The χ2 test was used for comparing non-parametric data. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant, p < 0.001 was considered highly significant, and p > 0.05 was considered not significant.

Results

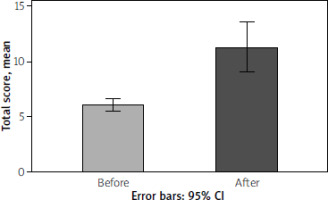

The BDI scores showed a significant increase across all questionnaire items after corticosteroid therapy. The mean total score was 6.02 ±2.05 before corticosteroid therapy and 11.28 ±7.94 after therapy, showing a significant increase in total score after corticosteroid therapy compared to before therapy (p < 0.001), as presented in Table I and Figure 1.

Table I

Clinico-demographic characteristics of the studied patients

Comparison of clinical and laboratory data before and after corticosteroid therapy intake among the studied cases revealed significant changes in body mass index (BMI), C-reactive protein (CRP), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), serum total calcium, and systolic blood pressur e (p < 0.001), as presented in Table II.

Table II

Clinical and laboratory data before and after corticosteroid therapy intake among the studied cases

According to the BDI scores, none of the participants exhibited depression prior to corticosteroid therapy (0%). After corticosteroid therapy, 13 (26%) participants had depression; 10% were mild, 6% were moderate, 8% were severe, and 2% were very severe. Depression levels were notably elevated following corticosteroid treatment compared to pre-treatment levels therapy, as shown in Tables III and IV and Figure 1.

Table III

Beck Depression Inventory before and after corticosteroid therapy among the studied cases

Table IV

Relation between degree of depression and corticosteroid therapy among the studied cases

The presence of depression and severity of depression were significantly higher with a CS dose > 40 mg/dl compared to a dose of 20–40 mg/dl, as shown in Table V.

Table V

Association between degree of depression and dose of corticosteroid therapy among the studied cases

Discussion

Previous studies found significant depressive symptoms and depression among individuals receiving CS as treatment. Brown and Supps reviewed the existing literature on mood symptoms while undergoing corticosteroid treatment. Only a small number of studies have applied widely accepted symptom measures or clearly outlined diagnostic criteria to describe these mood changes. Available data indicate that symptoms of psychosis, depression, mania, and hypomania are prevalent during therapy. Symptoms seem to be influenced by the dosage and typically manifest within the initial weeks of treatment. The risk factors for the onset of mood instability or psychosis remain unidentified [10, 11].

The main aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of depression among a sample of autoimmune patients receiving CS as treatment and assess whether the symptoms of depression are dose-dependent.

The present study aimed to determine the incidence of depression in a group of autoimmune patients undergoing CS treatment and investigate whether the severity of depressive symptoms correlates with the dosage of medication.

Consistent with our findings, Kershner and Wang-Cheng found that steroid-induced psychiatric symptoms are relatively common, affecting approximately 6% of all patients receiving steroid treatment. Typical symptoms include mood disorders such as depression and frank psychosis. Prior to starting steroid therapy, it is difficult to predict who is at the highest risk. However, it seems that women, individuals with SLE, and potentially those with a premorbid personality disorder may be at a slightly elevated risk. A prednisone dosage exceeding 40 mg/day elevates the risk, making it a crucial factor to consider. Symptoms typically appear early, usually within the first 2 weeks.

The type and severity of symptoms do not appear to be influenced by either the dosage or the duration of therapy. Side effects typically resolve quickly once the steroids are ceased [12].

In agreement with our study, in the meta-analysis and systematic review by Gerner and Wilkins, the authors examined cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cortisol in 22 healthy controls, 30 depressed patients, 21 women with anorexia nervosa, and 10 manic patients. All patients were assessed using a global severity scale for mania or depression. The results showed elevated levels of CSF cortisol in all 3 patient groups compared to controls. The group that was depressed showed a notable positive correlation between CSF cortisol and severity ratings [13].

Furthermore, the study of Reckart and Eisendrath [14] revealed a strong association between exogenous corticosteroid impacts on cognition and mood. Eight patients who underwent more than 5 years of intermittent CS treatments volunteered to participate in interviews about their experiences. Seven patients reported that their physicians did not inform them about the potential psychiatric side effects. Five patients did not notify their physicians when symptoms arose. The patients reported experiencing hypomania or euphoria, depression, confusion, insomnia, and memory problems. These reports demonstrate the frequency of affective and cognitive side effects caused by exogenous CS.

Consistent with the current study, Bolanos et al. found that mood disorders and symptoms are prevalent in corticosteroid-dependent patients. According to clinician-rated assessments, long-term prednisone therapy is more likely to be linked to depressive rather than manic symptoms, unlike short-term therapy. Prednisone may have a greater impact on mood symptoms in individuals on the ISS compared to clinician-rated scales [15].