INTRODUCTION

Beta-lactam (BL) antibiotics are the most widely used antimicrobial drugs. According to the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption Network data from 2022, the most used antibiotics in outpatient care (both across the Europe and in Poland) in 2021 were penicillins. In hospital care, the most used drugs in Europe were penicillins, but in Poland cephalosporins and other BL antibiotics [1]. It is estimated that actual hypersensitivity to penicillin is found in only 5% of patients reporting “penicillin allergy” [2–5]. Hypersensitivity to other BL antibiotics, such as cephalosporins and carbapenems averages less than 2% [6, 7]. Anaphylaxis after BL antibiotics admission is rare, although at the same time penicillins are the most common cause of drug-induced anaphylaxis [8].

Diagnosis of hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics includes:

in vivo tests: skin prick tests (SPT) with undiluted drug, intradermal tests (IDT) with a specific non-irritant concentration, and drug provocation tests (DPT),

in vitro tests: allergen-specific IgE (sIgE) of selected antibiotics.

According to the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) position paper on the diagnosis of hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics, when IgE-dependent hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics is suspected, it is recommended to perform skin tests 3 to 6 weeks after the hypersensitivity reaction. It is suggested to use major and minor benzylpenicillin determinants, benzylpenicillin, amoxicillin, and any other suspected BL. If determinants are unavailable, testing is recommended with a commercially available BL antibiotic [9]. According to a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis, the sensitivity and specificity of skin tests are estimated to be 30.7% and 96.8%, respectively [10]. DPT remain the gold standard for the diagnosis of hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics. In high-risk patients, it is recommended to perform DPT according to the scheme 1% → 10% → 40% → 49% (alternatively 1% → 5% → 15% → 30% → 49%) of the maximum single dose of the drug, while in low-risk patients according to the scheme 10% → 40% → 50% of the maximum single dose. Intervals between doses should be between 30 and 60 min. DPT are contraindicated in patients with severe non-immediate reactions and a history of severe anaphylaxis [9]. Among in vitro methods, the most common method of diagnosing immediate hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics is the determination of a selected allergen-specific IgE serum level. Due to its relatively low sensitivity and high rate of false positive results, the usefulness of this method is limited. It is mainly used in high-risk patients and patients with contraindications for SPT, IDT and DPT [11–13].

Risk stratification in the diagnosis of antibiotic hypersensitivity remains a focus of scientific interest [14–18]. The previous EAACI position paper recommended a full work-up including SPT, IDT and DPT in patients with suspected hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics [19, 20]. According to the current EAACI position paper, it is recommended to stratify the diagnostic risk, but skipping skin tests is only recommended in pediatric patients with mild maculopapular exanthema (MPE) and patients with palmar exfoliative exanthema [9].

Over the past decade, scientific interest in the over-recognition of BL antibiotic hypersensitivity has significantly increased. Diagnostic methods of BL hypersensitivity remain the same for years.

AIM

The aim of our study was to analyze the relevance of diagnostic methods, such as laboratory tests, skin tests and provocations in patients with reported BL allergy in different diagnostic risk groups.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

MATERIAL

In a single-center, retrospective study, we analyzed the medical records of patients hospitalized due to hypersensitivity to at least one BL antibiotic at the Department of Allergology and Clinical Immunology of the Prof. K. Gibinski University Clinical Center in Katowice from January 2018 to June 2022.

Inclusion criteria for analysis were as follows: 1. Patients with a history of suspected hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics. 2. Age over 18 years. 3. First-time diagnosis of antibiotic hypersensitivity. 4. No severe chronic/acute illnesses.

Exclusion criteria for analysis were as follows: 1. Patients with suspected hypersensitivity only to drugs other than BL antibiotics. 2. Patients previously diagnosed with antibiotic hypersensitivity. 3. Patients with severe chronic/acute diseases.

METHODS

The database included a detailed medical history, laboratory test results and allergy work-up.

The following data were analyzed:

Demographic and anthropometric data: age, gender, body mass index (BMI).

Comorbidities: diagnosed IgE-dependent allergic diseases, such as seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR) and perennial allergic rhinitis (PAR), asthma and smoking.

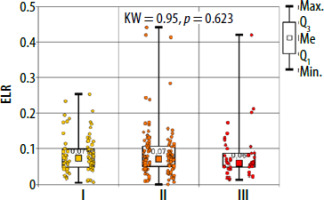

Laboratory test results: selected parameters of peripheral blood count (number of platelets, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils), tryptase concentration, total IgE concentration, concentration of sIgE to specific BL antibiotics. After the results were obtained, the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (ELR) were calculated by dividing the absolute number of platelets, neutrophils and eosinophils, respectively, by the absolute number of lymphocytes.

Results of the allergy work-up included skin prick tests, intradermal tests and provocation with selected BL antibiotics.

Based on the history data, patients qualified for analysis were divided into three groups following the criteria proposed by Shenoy et al. [21] (Table 1 [22]). The criteria were applied to patients reporting hypersensitivity to penicillins and cephalosporins.

Table 1

Diagnostic risk groups according to Shenoy et al. [21]

| Group I Low risk | Group II Moderate risk | Group III High risk |

|---|---|---|

| Isolated non-allergic symptoms: e.g., headache, uncharacteristic gastrointestinal symptoms Pruritic skin without skin lesions Remote (> 10 years) vague reactions without features suggesting an IgE-dependent mechanism Family history of the allergy to penicillins | Urticaria or other skin lesions accompanied by pruritus Reactions with isolated symptoms suggesting an IgE-dependent mechanism, but without symptoms of anaphylaxis | Anaphylaxis – diagnosis based on modified Sampson criteria [22] Recurrent hypersensitivity reactions Confirmed hypersensitivity to multiple BL antibiotics Positive skin test results |

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For quantitative characteristics, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis (KW) test was used to compare the study groups. Continuous parameters with not normal distribution were presented as median and interquartile range. For qualitative variables, statistical analysis was performed using the non-parametric test of independence χ2. Calculations were performed with a software package (The Statistica 13.3, StatSoft Polska, Kraków, Poland). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

From January 2018 to June 2022, 1957 patients referred for drug hypersensitivity diagnosis were hospitalized in the Department of Allergology and Clinical Immunology of the Prof. K. Gibinski University Clinical Center in Katowice. Among them, 391 patients were hospitalized due to reported antibiotic hypersensitivity. 128 patients hospitalized due to hypersensitivity other than to BL antibiotics were excluded from the study. In the final analysis, 263 patients were included and classified into three groups. The low-risk group consisted of 88 (33.46%) patients (group I), moderate risk of 129 (49.05%) patients (group II), while the remaining 46 (17.49%) patients were classified to the high diagnostic risk group (group III).

The results presented below are a continuation of another study on hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics, therefore detailed general characteristics and accurate interview data are presented in the previously published article [23].

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DIAGNOSTIC RISK GROUPS

Based on the result of the independence test, the same gender structure was found in the three groups. The prevalence of seasonal and perennial rhinitis, asthma and smoking did not differ significantly between the diagnostic risk groups. Detailed data are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

General characteristics of patients in the diagnostic risk groups

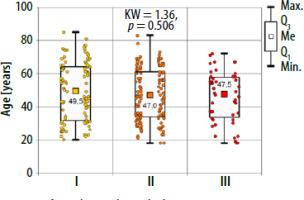

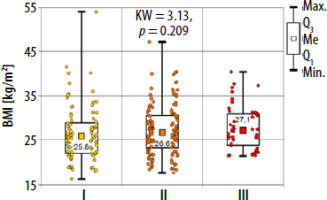

There were no significant differences in age and BMI between the studied groups (Kruskal-Wallis test) (Figures 1, 2).

RESULTS OF LABORATORY TESTS AND ALLERGY WORK-UP

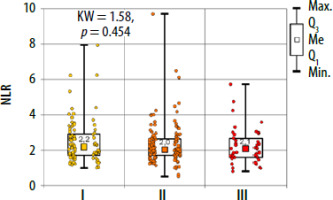

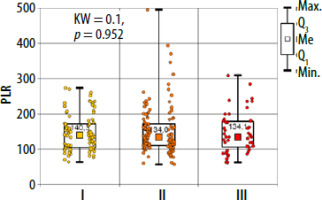

There were no significant differences between the study groups both for peripheral blood parameters and NLR, PLR and ELR ratios (Table 3, Figures 3–5). There were no differences in basal tryptase levels between the groups. Tryptase levels were determined in 25 (9.5%) patients. Increased tryptase concentration (> 11.4 µg/l) was observed in 1 patient in group II. The total IgE values were characterized by significant scatter and distribution asymmetry. Increased total IgE concentrations (> 87 µg/l) were found in 40 (15.2%) patients. Total IgE concentrations did not differ between the study groups.

Table 3

Laboratory tests results and calculated ratios in the diagnostic risk groups

Due to the insufficient number of specific IgE levels against BL, performing statistical analysis was possible only for cefaclor, with no confirmed statistically significant differences (Table 4).

Table 4

Positive results of allergen-specific IgE in the studied groups

Detailed characteristics of the performed allergological work-up is presented in Table 5. In 23 (8.7%) patients, hypersensitivity to a BL antibiotic was confirmed regardless of the risk group. Among the patients with positive skin tests (10/263, 3.8%) or provocation tests (13/263, 4.9%), 6 (2.3%) were diagnosed with hypersensitivity to the BL ring, 2 (0.76%) were diagnosed with cross-sensitivity between aminopenicillin, and amino-cephalosporin, 3 (1.14%) were diagnosed with hypersensitivity to two BL antibiotics from different groups, while 12 (4.5%) had confirmed hypersensitivity to the reported BL antibiotic, including 6 (2.3%) with IgE-independent hypersensitivity to the reported BL antibiotic.

Table 5

Results of allergological diagnosis in the diagnostic risk groups

DISCUSSION

In our study, we characterized patients with low, moderate and high-risk hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics, based on the laboratory test results and allergy work-up. There were no differences between laboratory results in different diagnostic risk groups. We ruled out reported hypersensitivity more often in the low-risk group compared to the other groups.

LABORATORY TEST RESULTS

The utility of laboratory tests in the diagnosis of BL antibiotic hypersensitivity remains limited. Sousa-Pinto et al. presented a systematic review and meta-analysis, in which authors analyzed eleven studies evaluating the summarized sensitivity of sIgE for penicillins, which was estimated at 19.3% (95% CI: 12.0–29.4%), and specificity at 97.4% (95% CI: 95.2–98.6%) [10]. Lowering the positive cut-off point from 0.35 kU/l to 0.1 kU/l increased sensitivity but decreased specificity, especially in those with total IgE levels > 200 kU/l [24]. The data were confirmed by a recent study published by Ariza et al. in which a cutoff value ≥ 0.10 kUA/l increased the sensitivity of sIgE detection for penicillin G and/or amoxicillin from 15.5% to 39.6% in Spanish patients and from 32.4% to 52.4% in Italian patients compared with a cutoff value of ≥ 0.35 kUA/l. However, the specificity of the test decreased from 93.8% to 68.8%. For penicillin G, a false-positive result was obtained in 16% of the tested individuals [11]. Fontaine et al. showed that the sensitivity and specificity of the sIgE for BL antibiotics depends on the severity of the hypersensitivity reaction [25]. In our analysis, due to insufficient numbers in the study groups, statistical significance calculation was only possible for cefaclor sIgE, for which no statistically significant differences were found. In addition, positive sIgE for BL antibiotics had no effect on further allergy diagnostic steps. Two patients with positive sIgE for amoxicillin from group II were delabeled.

In our analysis, basal tryptase determination was performed in a total of 26 patients, among whom 1 person from group II was found to have a concentration > 11.4 µg/l. According to the EAACI position paper on in vitro diagnosis in drug hypersensitivity, it is recommended to determine the tryptase concentration 30–120 min after the onset of the hypersensitivity reaction and to compare the obtained result with the basal concentration before the hypersensitivity reaction [24], which is not possible in the routine diagnosis of hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics.

In allergic diseases, the usefulness of NLR, ELR and PLR ratios was demonstrated for asthma, allergic rhinitis and nasal polyps [26–29]. The usefulness of the above indicators in drug hypersensitivity was described only for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) and in patients with cutaneous drug hypersensitivity syndromes [30, 31]. In a study by Dundar and Daye, the authors presented that NLR is a useful prognostic indicator of generalized inflammation in patients with drug-induced cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions. The median NLR in patients with erythema multiforme/Stevens Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis was significantly higher than the median NLR in patients with maculopapular exanthema and fixed drug eruption (p = 0.022 and p = 0.015, respectively) [31]. In our analysis there were no statistically significant differences between NLR, ELR and PLR ratios in the studied groups.

It seems that the results of laboratory tests are not useful in routine BL hypersensitivity diagnosis.

SKIN TESTS AND DRUG PROVOCATIONS

Skin prick tests, intradermal tests and provocation tests with selected drugs, despite many limitations, are still the method of choice in the diagnosis of hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics [9, 32]. In the previously mentioned systematic review and analysis by Sousa-Pinto et al. the sensitivity and specificity of skin testing were estimated at 30.7% (95% CI: 18.9–45.9%) and 96.8% (95% CI: 94.2–98.3%) respectively, with a partial area under the ROC curve of 0.686 [10]. In some European countries, including Poland, penicillin determinants are not available, therefore skin tests are performed with commercially available drugs [32]. During provocation tests, subjective symptoms reported by patients can cause difficulties in confirming or ruling out the hypersensitivity. Severe hypersensitivity reactions after drug provocations are rare. In a meta-analysis of 112 studies regarding penicillin provocation tests, among 26,595 participants, severe hypersensitivity reactions were found in only 0.06% of subjects [33]. Limitations of skin testing and provocation tests include the inability to perform planned diagnostics in the presence of cofactors, such as inflammation.

In a recently published study by Iuliano et al., hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics was diagnosed in 18.3% (86/471) of patients, of which 13.4% (63/471) were diagnosed with immediate hypersensitivity and 4.9% (23/471) with IgE-independent hypersensitivity [34]. In our ward, hypersensitivity to a BL antibiotic was confirmed in a total of 11.4% (23/263) of patients, including IgE-independent hypersensitivity in 2.3% of subjects (6/263). BL ring hypersensitivity was diagnosed in 6 (2.3%) subjects. However, this diagnosis should be approached critically as it is often made “over the top” in patients whose diagnosis confirms hypersensitivity to two different BL antibiotics. Additional testing with monobactam (which does not cross-react with other BL antibiotics) would allow unequivocal confirmation or exclusion of hypersensitivity to the entire BL ring and probably reduce the percentage of patients with this diagnosis. In contrast, cross-sensitivity between penicillins and amino cephalosporins was confirmed in 0.76% (2/263) of subjects. Analyzing the available data, it emphasizes the relationship between the similarity in the structure of the R1 side chain, less frequently R2, and the incidence of cross hypersensitivity reactions in the BL antibiotic group [35–38]. At the same time, Macy et al. showed that the incidence of new hypersensitivity reactions to ampicillin, cefalexin and cefaclor, having an identical side chain at the R1, differed slightly between patients reporting hypersensitivity to the above-mentioned antibiotics and the group of patients without a history of hypersensitivity (0.87% and 0.70%, respectively). These data argue against clinically relevant cross-sensitivity between BL antibiotics with identical side chains in patients with an unconfirmed history of hypersensitivity [39].

In our study, BL allergy was ruled out in 52 (59.8%) patients in the low diagnostic risk groups, and in the medium and high-risk groups, in 27 (20.9%) and 2 (4.3%) patients, respectively. A matter of concern remains the fact that in the low diagnostic risk group, allergy to BL antibiotics was ruled out only in about 40%. It is worth noticing that a significant percentage of the patients were tested with antibiotics other than BL, and the diagnosis of hypersensitivity to BL was scheduled for the next hospitalization in the future. Given the rare occurrence of multi-drug allergy syndrome (MDAS) [40], one would question whether typing alternative antibiotics, especially in low diagnostic risk, is necessary. On the other hand, in almost 1/5 of patients in the medium-risk group allergy to the reported BL antibiotic was ruled out. This could be explained by the fading of hypersensitivity and the fact that additional cofactors, such as inflammation, were not present at the time of diagnosis.

In our analysis, each patient, regardless of the diagnostic risk group, firstly had skin tests, and only after negative skin test results, DPT was performed. This strategy is the most reliable method, but at the same time has the highest medical risk, costs and may involve the induction of hypersensitivity after DPT [41–43].

According to the EAACI position paper on the diagnosis of hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics, it is recommended that skin tests precede provocation tests regardless of the risk group and severity of the hypersensitivity reaction. Only in children with mild maculopapular exanthema and patients with palmar erythematous and exfoliative lesions, skin tests are not necessary before conducting provocation testing [9]. In contrast, a major change has been proposed in the latest EAACI/ENDA position paper on drug provocation testing, in which delabeling based on history alone is recommended in patients with non-hypersensitivity side effects only (e.g. vomiting, diarrhea, headache, yeast infection), family history of drug allergy, or in the one who tolerated the same drug after an initial reaction. In patients with mild maculopapular exanthema and an unknown reaction (that clearly that did not require treatment or emergency medical attention) skin tests are optional. In the remaining patients with a higher diagnostic risk, skin tests are mandatory, before DPT [13].

In conclusion, the data obtained in our analysis will improve the knowledge on the allergological work-up in patients hospitalized for suspected BL hypersensitivity. Further research is needed to identify risk factors for hypersensitivity to BL antibiotics.