INTRODUCTION

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) antagonists, introduced in the 1990s for the treatment of immune-mediated diseases, are characterized by high efficacy and safety. Anti-tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNF-α) agents are used in the treatment of chronic inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, inflammatory bowel diseases, and psoriasis.

Adalimumab is a recombinant human IgG monoclonal antibody directed against TNF-α. It is a fully humanized antibody, which reduces the risk of immunization during therapy. It is available in the form of subcutaneous injections, facilitating self-administration of the medication at home [1]. As adalimumab is increasingly used in treating inflammatory diseases, potential side effects remain of concern to both patients and physicians.

The most common adverse reactions of biologic drugs, including TNF-α inhibitors, are transient injection site reactions (ISRs), occurring with a frequency ranging from 0.5% to 40% [2]. In the case of adalimumab, these reactions may affect up to 20% of patients [3].

Injection site reactions are usually mild, manifesting as swelling, erythema, itching, and occasionally pain. These symptoms typically resolve spontaneously within 5 days. These reactions typically decrease in frequency and severity with subsequent administrations of the drug [4, 5].

Based on clinical presentation and allergological test results, two types of ISRs can be distinguished: irritative reactions and immune-mediated ISRs [6, 7]. The first type typically occurs within 24 h and quickly resolves [7, 8]. The second type of ISRs appears individually after prolonged drug administration [9, 10], typically emerging several days after the injection and persisting for 3–5 days [6, 9, 10]. In the case of immune-mediated ISRs, an early positive intradermal test result combined with a negative delayed test suggests an immediate IgE-mediated reaction, whereas a positive delayed intradermal test result indicates cell-mediated pathway involvement in the reaction [6].

It is estimated that 8% of patients treated with anti-TNF preparations experience a “recall reaction”, which resembles an ISR. This reaction occurs at sites of previous drug injections and typically manifests as erythematous and edematous plaques, with the presence of superficial perivascular T cell lymphocytic infiltrates [10, 11]. The pathomechanism of these reactions is not well-established; however, certain theories have emerged that might explain the root of the so-called “recall phenomenon”. These include: (1) damage of the vasculature, (2) epithelial stem cell inadequacy and sensitivity, (3) drug hypersensitivity reaction, and (4) increased local vascular permeability or proliferative changes due to a previous injection site. Due to the limited amount of literature and the predominance of individual case reports, the risk of experiencing a ‘recall reaction’ has not been clearly determined. The likelihood of the reaction depends on the patient, the provoking agent and the nature of prior tissue damage [12–14]. During therapy, no additional environmental or pharmacological triggers were identified in our patients.

AIM

In this case study, we present the case of a patient treated for plaque psoriasis who, during therapy with adalimumab, developed ISRs followed by the development of recall reactions, which resolved only after switching to a different biologic medication.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old woman with plaque psoriasis diagnosed at the age of 17, after having exhausted available therapeutic options including UVB 311 phototherapy and systemic treatment with cyclosporine, methotrexate, and acitretin, was qualified for biological treatment with the original formulation of adalimumab (brand name: Humira, AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL, USA, obtained from the Hospital Pharmacy of the Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland), with an initial dose of 80 mg, second dose after 1 week: 40 mg, maintenance dose: 40 mg every 2 weeks).

Initially, after 4 doses of the medication, a rapid improvement in the local condition was observed, achieving a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75).

After administration of the 8th dose, an erythematous-edematous reaction was observed at the injection site, resolving within 24 h (Figure 1). After the subsequent two doses, skin lesions of similar morphology recurred, spreading over a larger area of the skin. The skin lesions presented as well-demarcated, pruritic erythematous-edematous plaques (Figure 2). Antihistamine treatment was initiated, leading only to resolution of itching. Due to progressively worsening symptoms upon subsequent administrations, anti-TNF therapy was discontinued.

The patient underwent a dermatological and allergological diagnostic evaluation [12]. A skin biopsy was collected from the erythematous-edematous lesions. Histopathological examination of the affected skin revealed focal vacuolization of basal-layer keratinocytes and an infiltration consisting of neutrophils and T-cells with a CD4/CD8 phenotype. This finding aligns with observations by other authors [6, 10], confirming the drug-induced origin of the skin lesions and indicating the involvement of a delayed-type, T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction in the development of the lesions.

Epidermal patch testing was performed using the basic “True test” set and specific IgE levels were measured to exclude latex allergy potentially arising from the needle cover. Only the area exposed to Kathon G showed erythema and vesicles at both 48 and 96 h.

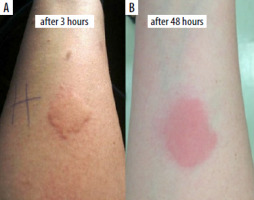

To investigate drug allergy, patch and intradermal tests were conducted with adalimumab (0.5 mg/ml at a 100-fold dilution). No immediate reaction was observed 30 min post-testing. The positive control (histamine) resulted in a wheal of 11 × 40 mm, whereas the negative control (physiological saline) showed no reaction (0 × 0 mm) (Figure 3). However, 3 h after administration of adalimumab, a wheal measuring 38 mm in diameter appeared at the injection site, evolving after 2 days into an erythematous-infiltrative lesion (Figures 4 A, B). No reaction was noted at the site of the adalimumab patch test.

Figure 3

Intradermal tests with adalimumab (A) preparation (0.5 mg/ml after 100-fold dilution). Positive control – histamine 11/40 mm, negative control – saline 0/0 mm

Figure 4

At the adalimumab injection site: urticarial wheal (A), erythematous-infiltrative lesion (B)

Clinical manifestations of “recall reactions” vary; however, in progressive stages, they may lead to skin necrosis, spontaneous bleeding, and even death, often necessitating an early change in therapy [13]. The exact cause of the reaction remains uncertain but may be associated with the long-standing history of plaque psoriasis, for which immune-modulating agents were used, or with a drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction to adalimumab. Therefore, taking into account disease progression, the presence of recall reactions (Figure 5), and positive intradermal test results, the decision was made to switch the patient’s treatment to an IL-12/23 inhibitor, which has been continued with a good therapeutic effect to this day.

DISCUSSION

According to the literature [5, 9, 13, 14], only a minority of patients undergoing anti-TNF therapy need to discontinue or transition to an alternative biologic agent.

In most patients who initially report adverse reactions related to anti-TNF therapy, these reactions usually resolve upon continued treatment [10, 11]. In cases of recurring reactions, a reduction in severity and frequency of symptoms is often observed, typically not necessitating a change of medication [9]. However, in our patient, we observed prolonging ISR symptoms with continued therapy, followed by the appearance of recall-type reactions, recurring with subsequent doses.

Reports from other authors indicate that in patients experiencing recurrent recall-type reactions, repeated administration of the drug may lead to life-threatening reactions. Therefore, we decided to discontinue the medication and perform allergological diagnostics [13, 15].

For effective assessment of the observed skin reactions, patch tests, intradermal tests, serum-specific IgE and IgG testing against TNF-α inhibitors, and histopathological examination of skin lesion biopsies are necessary [6, 10]. One study revealed that, among patients receiving biologic therapy, the detection of IgG4 serves as a valuable tool for identifying immunogenicity, adverse reactions, or a poor response to the medication [16].

Based on allergological test results, including a positive intradermal test with the drug (persisting for several days, observed only during late readings), along with negative prick and patch tests, we confirmed a type IV beta delayed hypersensitivity reaction according to Pichler’s classification as the cause of skin lesions in our patient [6, 8, 17]. The lack of improvement following antihistamine treatment confirmed the non-histamine-dependent nature of the skin reactions, consistent with other authors’ observations [6, 8].

Additionally, during therapy, we observed progression of psoriatic lesions, indicative of a possible paradoxical reaction to the initiated treatment. According to reports by other authors [15, 18, 19], this reaction is most frequently observed in women aged 30–50 with a familial predisposition to psoriasis. It typically develops several months after initiating therapy, as was the case in our patient.

The World Allergy Organization’s Systemic Allergic Reaction Grading System identifies reactions limited to the skin, without affecting the mucosal, respiratory, cardiovascular, or gastrointestinal systems, as Grade I, indicating a minimal risk of anaphylaxis. In our patient, each therapy session resulted in skin-related reactions only without any extracutaneous symptoms, aligning with Grade I WAO criteria and confirming the low likelihood of a severe reaction [20].

The most effective strategy to prevent upscaling recall-type skin reactions in our patient was discontinuation of the drug causing recurrent and concerning symptoms. Interestingly, reintroducing the medication after a break does not always trigger this reaction again [13].

The decision to switch from adalimumab to an IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor proved effective in treating our patient. IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors demonstrate high efficacy and may represent a valuable alternative to anti-TNF-α drugs, as confirmed by other authors [13, 14].

CONCLUSIONS

In patients treated with anti-TNF drugs who experience ISR-type reactions and persistent recall reactions, performing intradermal tests with the administered drug is recommended. If delayed, lymphocyte-mediated hypersensitivity is confirmed, the decision to discontinue therapy or switch to another medication should be made based on clinical assessment.