Introduction

The global epidemic of obesity has reached every corner of the world, with large proportions of the population being obese, including 60% of the adults in the United States (US) [1]. Obesity-associated diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), have also reached record prevalence in most developed countries [1]. In this context, liver diseases associated with obesity and T2DM, specifically metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD; formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD), pose a growing global burden. MASLD affects 25–30% of the global population based on published meta-analytic global assessment of its prevalence [2]. MASLD encompasses a spectrum of liver diseases that occur in the absence of other known causes, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is the severe form of MASLD (Figure 1) [3]. It is histologically defined by lobular inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning, and it is associated with a greater risk of fibrosis progression [4]. Liver fibrosis is categorized into 5 stages, ranging from no fibrosis (F0) to cirrhosis (F4). While cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality in patients with MASLD, those with severe liver fibrosis are at an increased risk of liver-related mortality, with the risk escalating exponentially with the fibrosis stage [3]. MASH has become one of the leading causes of adult liver transplantation among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) undergoing liver transplantation, primarily due to the lack of medical treatments that target and reverse fibrosis, and it is projected to continue increasing [5].

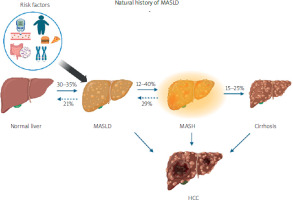

Figure 1

Progression of metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). The spectrum begins with a healthy liver. Under various clinical conditions it can develop into simple steatosis and subsequently metabolic-associated steatohepatitis associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Both simple steatosis and MASH are potentially reversible stages. However, if MASH progresses to cirrhosis, the histopathological changes become irreversible and may further lead to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Additionally, genetic predispositions, environmental factors, and coexisting diseases can influence the onset and progression of MASLD [3]

Before the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of resmetirom, MASH and MASLD were managed by lifestyle modifications, including weight loss interventions, diet and exercise. In March 2024, resmetirom became the first drug approved by the US FDA along with diet and exercise for the treatment of adults with non-cirrhotic MASH (consistent with stages F2 to F3 fibrosis) [5]. Both resmetirom and GLP-1RAs have shown promising results in treating various metabolic disorders. Resmetirom has demonstrated efficacy in treating MASH and dyslipidemia. While GLP-1RAs are widely used for T2D management, they have been reported to reduce liver fat content likely through weight loss; however, the exact mechanisms remain unclear [6]. Combining both resmetirom and GLP-1RA might address the overlapping mechanisms driving these conditions more effectively than either agent alone. It could enhance overall treatment outcomes, improve patient quality of life, and reduce the burden of these diseases on healthcare systems. This article will discuss the use of each agent alone, their benefits, and the potential advantages of combining both treatments.

Resmetirom

Over the years, researchers have concentrated on targeting typical pathways implicated in MASH progression, including lipogenesis, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Despite extensive efforts, these strategies have failed to yield approved therapies. The success of resmetirom brings to light why thyroid hormone receptor-β (THR-β) agonists have shown promise while other approaches have fallen short [7]. Resmetirom is an orally active agonist and has higher selectivity than triiodothyronine (T3) for THR-β. In MASH, impaired THR-β function in the liver reduces mitochondrial function and β-oxidation of fatty acids, consequently leading to increased fibrosis [8]. In the MAESTRO-NASH trial, the dual primary endpoints at week 52, for both doses – 80 mg once daily and 100 mg once daily – were superior to placebo and showed MASH resolution and fibrosis improvement. These histological endpoints are deemed likely to predict clinical benefit, given the strong correlation between MASH severity and liver-related mortality/transplant-free survival [9].

Thyroid hormones principally mediate their effects through two receptors, THR-α and THR-β. THR-β is the dominant receptor isoform in hepatocytes; it lowers cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and increases bile acid synthesis and fat oxidation. The association between overt primary hypothyroidism and increased hepatic lipids, as indicated by elevated serum thyrotropin (TSH) levels and markers of hepatocellular injury, has long been recognized [10], and individuals with low-normal thyroid function have shown an increased propensity for a MASLD diagnosis and higher liver fibrosis stage [11]. This prompted a phase 2b study of ultra-low-dose levothyroxine, which remarkably reduced liver lipid content in certain patient groups.

Resmetirom demonstrates promise in treating lipid metabolism disorders. It exhibits safety in rodents and efficacy in preclinical models without impacting the central thyroid axis [12]. Clinical trials in healthy volunteers have shown an excellent safety profile and lipid-lowering effects [9]. These findings pose several questions. Given the high mortality rate from CVD in this patient group, could resmetirom potentially reduce cardiovascular risk by lowering LDL cholesterol? Sub-analyses at the end of the trial could help identify which patient population benefits most from resmetirom treatment.

GLP-1RA

When we consume food, the enteroendocrine cells (EECs) release the peptide hormone GLP-1, which has several metabolic effects that are mediated by the seven transmembrane G protein-coupled GLP-1 receptors (GLP-1Rs) [13]. GLP-1 not only has strong effects on improving glucose-dependent insulin secretion, but it also reduces food intake and body weight by inducing satiety and suppressing gastrointestinal motility. The development of GLP-1 as an anti-diabetic and anti-obesity treatment was aided by these findings [14]. Given that T2DM and obesity are major risk factors for MASLD, there is increasing clinical interest in investigating the therapeutic effects of GLP-1RAs on MASLD. Clinical trials in patients with MASLD have consistently shown significant reductions in liver fat content, as detected by MRI analysis, following treatment with exenatide, liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide [15, 16]. In a multicenter, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled phase-2 LEAN study conducted in the UK, daily subcutaneous injections of 1.8 mg of liraglutide for 48 weeks led to MASH resolution in 39% of patients compared to 9% in the placebo group. Additionally, there were slight but significant improvements in the histopathological parameters, with a higher percentage of patients showing reductions in the histological scores of the stages of Kleiner fibrosis, steatosis, and hepatocyte ballooning. Semaglutide significantly increased the proportion of patients achieving MASH resolution without worsening fibrosis [16]. A 5% weight loss achieved through calorie restriction can reduce liver volume by approximately 10% and decrease hepatic triglyceride content by 40% [17]. The mechanism of action whereby GLP-1RAs ameliorate MASLD and MASH is still a subject of debate. GLP-1R expression was not detectable in hepatocytes or hepatic stellate cells, suggesting that the liver is unlikely to be the direct target of GLP-1Ras. Some evidence suggests that GLP-1RAs induce the production of FGF21 through an indirect mechanism involving the brain-liver axis in mice, which may contribute to the alleviation of MASH and fibrosis [17]. Similarly, compared to placebo controls, T2DM patients treated with GLP-1RAs show elevated levels of FGF21 in the blood, and it has been demonstrated that FGF21 functions as a necessary mediator for the therapeutic effects of GLP-1RAs on the inhibition of hepatic glucose production and steatosis [18]. However, it is still unclear whether FGF21 is required for the anti-fibrotic and anti-MASH activities of GLP-1RA [19].

Theoretical basis for combination therapy

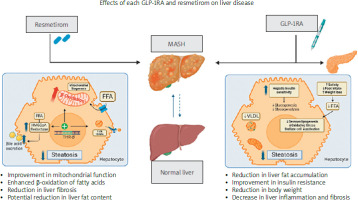

The combination therapy of an antisteatotic drug such as resmetirom with GLP-1RA, which addresses obesity and T2DM while minimizing action outside the liver, appears promising. This approach could represent a significant advancement toward an optimal therapeutic strategy for patients with MASLD and other metabolic disorders (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Effects of GLP-1RA and resmetirom on liver disease. The figure shows MASLD progression from a healthy liver to simple steatosis, MASH, and cirrhosis. It highlights GLP-1RA and resmetirom treatments at the MASH stage, depicting their effects on reducing liver fat, improving insulin resistance, enhancing mitochondrial function, and reducing fibrosis, leading to a healthier liver state

Enhanced lipid metabolism: Resmetirom targets hepatic lipid metabolism by selectively activating THR-β, leading to reduced hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation. As observed in the MAESTRO-NASH trial, significant improvements were noted in key atherogenic risk markers, including LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein C-III, and lipoprotein(a), compared to placebo at 24 weeks, with these benefits maintained at 52 weeks [11]. On the other hand, GLP-1RA influences lipid metabolism through various mechanisms such as promoting satiety and enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nevertheless, GLP-1RA does not seem to have a substantial effect on plasma lipid parameters; for instance, the estimated reduction in LDL levels is limited to about –3.7 mg/dl. However, it does decrease satiety and food intake, so combining these agents holds the potential for synergistic effects on lipid metabolism, reducing blood/liver lipids and liver steatosis [20].

Weight loss: Combining GLP-1RA and resmetirom treatments could result in greater weight loss compared to either treatment alone, due to their complementary mechanisms of improving metabolic profiles and enhancing liver function, as shown by a study on a diet-induced obese (DIO) and biopsy-confirmed mouse model of MASH with liver fibrosis. In addition, combination therapy amplified the hepatic transcriptomic profile [21].

Hepatic versus pancreatic targets: Resmetirom primarily focuses on hepatic lipid metabolism through THR-β activation, while GLP-1RA predominantly influences pancreatic function by stimulating insulin secretion and inhibiting glucagon release. Given the impact of glycemic control on ballooned hepatocytes and hepatic fibrosis in MASLD/MASH, optimizing glycemic control may mitigate the risk of MASH progression [22]. Moreover, it is essential to note that resmetirom appears to enhance the impaired health-related quality of life (HRQL) in MASH patients. Additionally, integrating GLP-1RA for weight management could significantly augment HRQL outcomes for these individuals [23].

Reduces liver inflammation/fibrosis: A study was conducted on mice evaluating combination therapy of resmetirom and tirzepatide effect on MASH through blood and liver samples biochemistry and histological analysis. The study showed a reduction in pro-inflammatory gene expression (IL-6 and IL-1b), MASLD activity, liver inflammation score, and liver fibrosis [24].

Cardiometabolic risk reduction: Resmetirom has shown favorable effects on lipid profiles, reducing levels of triglycerides and LDL cholesterol, which are key risk factors for CVD [11]. GLP-1RAs have also been associated with improvements in cardiovascular risk markers, including blood pressure and markers of inflammation [23]. Certain GLP-1RAs (liraglutide, semaglutide and dulaglutide) reduce the risk of major adverse CV events in patients with T2D at high risk of CVD. Subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg has shown beneficial effects on CV outcomes in the SELECT trial and in renal protection [25]. The cardioprotective effect may also be important for patients with MASLD/MASH, in whom CVD is a leading cause of death.

Anti-atherogenic effects: Both resmetirom and GLP-1RA have been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic properties. A study aimed to assess the impact of resmetirom on CVD progression (atherosclerosis) and found, in line with the strong reduction in circulating lipids, that it significantly reduced atherosclerosis lesions [26]. Resmetirom reduces hepatic inflammation and fibrosis, while GLP-1RAs attenuate systemic inflammation and inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation [23].

Endothelial function and vasodilation: GLP-1RAs have been reported to improve endothelial function and vasodilation, which are important determinants of cardiovascular health. Resmetirom may further enhance these effects through its modulation of thyroid hormone signaling pathways [23].

However, a major downside of both GLP-1RA and resmetirom is their adverse effects; GLP-1RA is known to cause gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Based on a clinical trial, resmetirom also was associated with significant gastrointestinal side effects, especially diarrhea [21]. Additionally, there are concerns regarding the risk of pancreatic, gallbladder, and bile duct events associated with GLP-1RAs, including pancreatitis and acute cholecystitis, necessitating close monitoring and potential discontinuation if suspected [16]. While resmetirom has generally been reported as safe, ongoing surveillance is essential to detect any potential endocrine disorders related to the thyroid gland, despite its high selectivity as a THR-β agonist. Furthermore, the pricing of resmetirom, estimated between $39,600 and $50,100 annually, and the cost of GLP-1RA, averaging $12,000 for uninsured patients, underscore the need for rigorous pharmacoeconomic analyses to ensure justifiable pricing aligned with clinical efficacy and safety standards, especially considering the requirement for long-term treatment [27].

Without a doubt, this is a historic time for the MASH field, not just for researchers and medical professionals, but also perhaps most for the patients who are dealing with this liver disease. Further research is required to address several unanswered questions in the field of combined resmetirom and GLP-1RA therapy. Long-term studies are needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of this combination, especially across diverse patient populations and different stages of metabolic disorders. Additionally, there is a need to gain mechanistic insights into the synergy between these agents, focusing on their impacts on lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, inflammation, and cardiovascular health. Determining optimal dosing regimens and treatment durations is crucial for maximizing therapeutic benefits while minimizing potential side effects. Furthermore, identifying patient subgroups most likely to benefit and developing predictive biomarkers for treatment response are essential for personalized treatment approaches.

Table I below shows a list of registered clinical trials focusing on individual management approaches for patients with liver disease [28–33].