MASTOCYTOSIS

Mastocytosis (MS) is a disease characterized by excessive degranulation and accumulation of monoclonal mast cells (MC) in one or multiple organs [1]. MS presents a wide spectrum of clinical forms. According to the latest classification proposed by the WHO, MS is divided into cutaneous mastocytosis (CM), in which there is only skin involvement, systemic mastocytosis (SM), and mast cell sarcoma [2]. Cutaneous mastocytosis is the most common form of the disease occurring in children. In general, CM has benign course and good prognosis as 50–60% of children improve by adolescence [3]. SM, in contrast to CM, typically develops in adults. Depending on the extent of organ involvement, patients may have a benign course with a normal lifespan or an aggressive one [4]. Among patients with SM, mast cells can accumulate in extracutaneous organs such as the bone marrow, spleen, liver, lymph nodes, and the digestive tract [5]. Suspicion of systemic mastocytosis is typically based on clinical symptoms and/or the elevated level of mast cell tryptase > 15 ng/ml [6]. However, a normal level of mast cell tryptase does not exclude systemic mastocytosis [7]. To diagnose MS, a histopathological examination is necessary, aiming to detect excessive proliferation and accumulation of mast cells in the affected organ [2]. Bone marrow biopsy is routinely performed to detect diagnostic infiltrates and examinate hematopoietic marrow which provides important prognostic information [1]. In further diagnostics, the presence of mutations in the KIT gene is determined, with the D816V (Asp-816-Val) point mutation being the most common. These mutations lead to the autophosphorylation of the c-KIT receptor, resulting in the differentiation, migration, accumulation, and activation of mast cells in tissues [8]. The full diagnostic criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria for systemic mastocytosis (SM) [2]

Subsequently, patients are classified based on the presence of B symptoms (indicating intensive infiltration of multiple organs) and C symptoms (indicating the organs damage and advanced form of the disease), allowing for the assessment of the disease stage (Table 2) [9]. Special attention should be given to the occurrence of symptoms such as progressive cytopenia, rapid increasing of the basal serum tryptase level or alkaline phosphatase, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, which may suggest an advanced form of the disease presenting as aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM), systemic mastocytosis with an associated haematological neoplasm (SM-AHN) or mast cell leukemia (MCL) [10] .

Table 2

B and C finding (proposed update) [9]

The symptoms of MS result from the infiltration of tissues by mast cells and the release of mediators contained in these cells [11]. The binding of antigen-specific IgE to FcεRI sensitizes mast cells and other effector cells to release mediators in response to subsequent encounters with that specific antigen or with cross-reactive antigens [12]. Activation of MC can also occur regardless of allergy in response to various biological substances inluding complement activation products, neuropeptides, bacterial products, cytokines, components of animal venom, chemicals, and physical stimulations [1]. Mediators released by MC include histamine, tryptase, heparin, prostaglandins, cytokines (including IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-13), chemokines (including MCP-1, MCP-3, MCAF, RANTES), and growth factors (including VEGF, PDGF, SCF, bFGF). The release of mediators and involvement of organs can cause symptoms affecting multiple systems, such as flushing, pruritus, diarrhoea, gastric ulcer disease, headaches, osteoporosis, depression, hypotonia, syncope as well as anaphylactic reactions [10].

THE DISTINCTIVENESS OF ALLERGY DIAGNOSTICS IN PATIENTS WITH MASTOCYTOSIS

Mastocytosis predisposes to severe, life-threatening anaphylactic reactions. It is estimated that the lifetime prevalence of anaphylaxis triggered by all factors ranges from 0.05% to 2% in the general population [13]. The risk of anaphylaxis is significantly higher for patients with mastocytosis, affecting 10–20% of them [14, 15]. The diagnosis of allergies through in vivo provocations in mastocytosis may be limited due to the possibility of anaphylaxis [16, 17].

The differences in diagnosis of hypersensitivity reactions (HR) in mastocytosis are well studied in Hymenoptera HR. Clinically significant systemic reactions after stings by Hymenoptera range from 0.3% to 8.9% in the general population [15, 16]. However, for patients with mastocytosis, the frequency of these reactions is often much higher, ranging from 22% to 49% for adults and from 6% to 9% for children. The predominant symptoms in these patients are vascular symptoms, such as hypotension and fainting.

The basis for diagnosing allergy to Hymenoptera, which allows qualification for specific immunotherapy, includes skin tests using venom extracts and the determination of specific IgE for allergens [18]. In some cases of mastocytosis, false-negative results can be obtained based on both diagnostic methods. One explanation for obtaining negative results is the binding of the majority of IgE to the surface of pathological mast cells through the IgE receptor, thus making IgE low detectable both in the serum and skin [19]. In patients undergoing mast cell-reducing therapy, specific IgE may become positive. Additionally, MC may be capable of desensitization in patients with MS. It should also be noted that falsely negative results in skin tests with Apis mellifera extract may be due to the absence of certain allergens, such as Api m10, in the allergen extract [20]. This necessitates exploration of changes in existing diagnostic methods, such as lowering the threshold for a positive sIgE result in patients with mastocytosis below 0.35 kU/L [21]. The threshold may be lowered to 0.17 kU/L in wasp venom allergy [22]. For patients with severe systemic reactions and negative results in sIgE and skin tests, consideration of other diagnostic methods is recommended, such as the basophil activation test (BAT) [23]. BAT is also applicable in the case of detecting dual sensitization to bee and wasp venoms, aiming to identify the primary allergen. Lifelong venom immunotherapy is recommended for patients with mastocytosis [24]. For this reason, it is important to measure the basal tryptase level in patients being diagnosed for venom insect allergy to refer them for mastocytosis diagnosis.

It is also worth mentioning the use of omalizumab, anti-immunoglobulin E monoclonal antibody, as a medication to enhance the safety of venom immunotherapy in certain patients with SM, due to a high risk of anaphylaxis in this group [25]. In the literature, there are several cases describing the use of omalizumab as a premedication during the induction of VIT, which previously could not be carried out due to anaphylactic reactions [26, 27].

GASTROINTESTINAL SYMPTOMS IN PATIENTS WITH SYSTEMIC MASTOCYTOSIS

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are frequently present in patients with systemic mastocytosis. It is reported that they occur in approximately 50–60% of patients [28–30], but some sources indicate that the occurrence of these symptoms can even reach up to 80–85% [31, 32]. Suspicion of GI involvement is based on clinical symptoms and endoscopic examination, while the diagnosis requires histopathological analysis using immunohistochemical studies (i.e., CD117, tryptase, CD25), indicating infiltration of the GI mucosa by MC [32]. These symptoms are associated with a reduced quality of life for patients [29, 31] and their similarity to symptoms of other medical conditions requires special attention during diagnosis. Symptoms such as bloating, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting are associated with the release of mediators from mast cells, while infiltrations in the intestines lead to absorption disorders and weight loss [33, 34]. Due to nonspecific nature, the symptoms may mimic other gastrointestinal diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome [35] or inflammatory bowel diseases [36]. Additionally, because of the intensity of abdominal and skin symptoms, patients may mistakenly diagnose themselves with food allergy; however, due to the fact that MC also undergo spontaneous degranulation, current studies do not confirm a higher prevalence of food allergies than in the general population [37, 38].

Based on a study conducted by Sokol et al. on a group of 83 patients with SM, most reported symptoms include diarrhoea and bloating, followed by nausea and abdominal pain [31].

The study performed by Doyle et al. also indicates, in addition to the aforementioned, weight loss, vomiting, and reflux [39]. In the group of patients with SM, the occurrence of peptic ulcers disease is also observed [30]. It is considered to be associated with the release of MC mediators both locally and systemically and consequently with secretion of gastric acid, however, studies on this subject are inconsistent [30]. In the paediatric population with SM, gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain are also one of the most commonly reported complaints [40].

In the normal lamina propria of the GI tract, mast cells constitute 2-5% of mononuclear cells [41]. Mediators released by MC play a role in the functioning and regulation of the GI tract. Infiltration of MC and their excessive activation can lead to gastrointestinal disorders [42]. It is worth noting that studies have demonstrated an increased number of mast cells in mucosal samples of the gastrointestinal tract in some cases of patients with other gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome [41]. In patients with SM, studies concerning this topic are not consistent. In endoscopic examinations of the GI tract in SM patients, abnormalities are not observed in 40% of cases [33]. In a study conducted by Doyle et al., endoscopic abnormalities, such as erythema, granularity, and nodules, were observed in 62% of patients with SM, additionally, involvement of mastocytosis was observed in only 66% of the mucosal biopsies conducted [39]. Many patients do not undergo the above procedures, making it difficult to determine the actual involvement [31, 39]. The absence of infiltration by mast cells in the gastrointestinal tract does not exclude the association with symptoms presented by patients with SM as mediators released by MC located in distant organs can induce GI symptoms [43]. In the study conducted by Sokol et al. mentioned above, a subgroup of patients with SM that underwent endoscopic examinations of the gastrointestinal tract showed specific histopathological patterns, including the presence of clusters of mast cells, their specific topography, and deviations in CD25 expression [31]. However, these features were not consistent and did not occur in all cases. Nonspecific changes were also described, such as partial villous atrophy and mild inflammatory infiltration associated with mast cells predominating over inflammatory cells. There was no clear correlation observed between mast cell infiltrates and gastrointestinal symptoms, except for an association between diarrhoea and dispersed mast cell infiltrates in the stomach. Similarly, in a study conducted on a group of 70 patients with gastrointestinal mastocytosis, no statistically significant association was found between GI symptoms and any specific location of GI involvement [34]. In reference to the above studies, due to the inconsistent nature of mastocytosis involvement in the gastrointestinal tract and the frequent presence of eosinophils [34, 39], which may dominate mast cell infiltrates, it is needed to obtain multiple mucosal samples from several different places during biopsy and perform appropriate immunohistochemical staining for correct diagnosis [39].

The variety of gastrointestinal symptoms of SM has been illustrated by the case report of a 63-year-old woman complaining of chronic abdominal pain [44]. The patient did not report any complaints other than abdominal pain, and there were no deviations in the physical examination or significant abnormalities in laboratory tests except for mild leucocytosis. However, imaging discovered a pathological mass in the cecum. Based on microscopic and immunohistochemical examination of the mass, mastocytosis was diagnosed. Despite the rare occurrence of isolated gastrointestinal symptoms in SM, this underlines the need to consider SM in the differential diagnosis of pathological masses in the GI tract.

The treatment of patients with SM aims to stabilize mast cells and control the release of mediators [45, 46]. In addition to avoiding triggers for acute mediator release from MC, pharmacotherapy is also recommended. In the first-line treatment of gastrointestinal manifestations, H2 receptor antagonists (such as famotidine) are used to reduce excessive gastric acid secretion. In subsequent lines, proton pump inhibitors are applied, followed by sodium cromoglycate that stabilizes the cell membrane of MC. Steroid treatment is applicable in specific cases such as organ damage.

GUT MICROBIOTA IN PATIENTS WITH MASTOCYTOSIS

The gut microbiota has a significant impact on the functioning of multiple organs, influencing metabolic, nutritional, physiological, and immunological processes [47]. The diverse bacterial species show the differential modulation of mediator secretion from MC [48]. Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Streptococcus pneumoniae have been observed to induce degranulation in MC. In contrast, probiotics and Escherichia coli demonstrate an inhibitory effect on degranulation in both human and mouse MC. In a study by Harcęko-Zielińska, the role of the gut microbiome in the pathogenesis of mastocytosis was analysed [49]. This involved examining 50 stool samples from patients with mastocytosis and 18 controls. Abnormal stool results were observed in 37 patients with mastocytosis, with the most common cause being an E. coli level < 106. Furthermore, the presence of pathogenic microorganisms such as K. pneumoniae and C. perfringens was identified. There was a correlation observed between mast cell serum tryptase and abnormal stool results, thus abnormal gut microbiota was more likely to be present in patients with aggressive variants of mastocytosis. As presented in a systematic review on mast cell activation and microbiotic interaction conducted by Afrin and Khoruts, microbiotic manipulations can affect MC activation as a potential treatment target in the future [50]. Therefore, there are numerous interactions between gut microbiota and mast cells, but the current state of knowledge create space for further research.

FOOD ALLERGIES IN PATIENTS WITH MASTOCYTOSIS

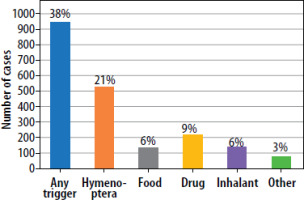

The most common factor triggering symptoms of mastocytosis include insect stings, food, and drugs [51, 52]. Figure 1 presents the classification of triggers inducing symptoms in SM, based on a study conducted on a group of over 2,000 patients. The frequency with which a given trigger induces a reaction may be dependent on the stage of disease [15]. Food HR is a broad term describing the presence of adverse symptoms to food in allergic, metabolic, toxic, pharmacologic, and unspecified mechanisms [53]. Food allergy (FA) is defined as an adverse health effect resulting from a specific immunologic response that occurs consistently upon exposure to a given food. Thus, food HR leads to the occurrence of IgE-mediated reactions or non-IgE-mediated disorders, such as eosinophilic esophagitis, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), or food protein-induced proctocolitis [54]. In recent decades, an increase in the frequency of food allergies has been observed in Europe. According to the review and meta-analysis regarding the prevalence of food allergy in Europe, based on the clinical history or positive food challenge, FA increased from 2.6% in 2000–2012 to 3.5% in 2012–2021 [55]. In relation to SM, special attention should be paid to the fact that commonly reported gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with SM may be incorrectly interpreted as FA. However, as mentioned before, based on the studies conducted so far, the frequency of food allergy in patients with mastocytosis is estimated to be comparable to the general population.

Jarkvist et al. conducted a study on a group of 204 patients with clonal mast cell disorders regarding HR to food [38]. Patients underwent comprehensive allergology diagnostics, including a medical interview, skin prick tests, and, if necessary, the determination of the levels of specific IgE antibodies. The prevalence of self-reported HR to food in this group was 20.6%. However, the frequency of immunologically mediated reactions was rare, only 3.4% were confirmed by a relevant history and IgE sensitization. The overall prevalence of food-induced anaphylaxis was 2.5%, while the lifetime prevalence of anaphylaxis in the general population, as mentioned, ranged from 0.05% to 2%. The majority of symptoms affected the skin (86%), followed by symptoms related to the gastrointestinal tract (45%), which were similar to the manifestations observed in patients with mastocytosis, even in the absence of allergy-suspected food consumption. In a large study conducted on 2,485 patients with MS, it was demonstrated that anaphylactic reactions to food were more prevalent in women [15]. The most reported triggers were nuts, alcohol, strawberries, peanuts, and fish. In another study, factors triggering anaphylaxis, including food, were investigated in a group of 152 patients with all types of mastocytosis [56]. Similarly, the medical history, skin prick tests and specific IgE were analysed. Symptoms of food intolerance was observed in 29% of patients. The majority of reported symptoms were not associated with IgE-mediated reactions; non-immunological hypersensitivity was diagnosed in 26% of patients. The authors suggested that symptoms may have been triggered by food rich in histamine. Food allergies were confirmed in 9% of patients. No difference was confirmed in the occurrence of IgE-mediated food-induced anaphylaxis between patients with SM and the general population. Also, in a study conducted by Pucino et al. on a group of 126 patients, there was no evidence of an increased prevalence of food allergies among patients with SM [37]. The majority of adverse reactions to food in patients in this study were not associated with positive skin prick test results or elevated levels of specific IgE, suggesting IgE-independent mechanisms as the cause of reported symptoms.

One of the studies focusing on food hypersensitivity and insect venom allergy in SM, demonstrated a significant difference in gene expression for TRAF4 when comparing SM patients with and without coexisting food hypersensitivity. TRAF-4 is involved in IL-25 signalling, which is implicated in Th-2-dependent responses, eosinophil recruitment, IgE production, and innate immune response. Thus, increased TRAF-4 expression could heighten the risk of food hypersensitivity [57].

Regarding aforementioned symptoms following consumption of food rich in histamine, it is suggested that biogenic amines and histamine-releasing foods may exacerbate symptoms occurring in SM. Vlieg-Boerstra et al. conducted a review of studies on mastocytosis and adverse reactions to biogenic amines and histamine-releasing foods [58]. No studies have been found in patients with mastocytosis using double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges. Correspondingly, in the recent study conducted by Bent et al. erythema and diarrhoea following histamine ingestion occurred with the similar frequency as after placebo ingestion [17]. Therefore, still the role of these diets remains uncertain [58] and they are not routinely recommended [11]. When discussing elimination diets due to suspected food allergies, it is also important to consider idiopathic anaphylaxis. In a group of patients with anaphylaxis, despite comprehensive allergy work-up, it is not possible to detect the triggering factor for symptoms, which is termed idiopathic anaphylaxis [54]. Clonal disorders of mast cells, including SM, can be misdiagnosed as idiopathic anaphylaxis due to overlapping symptomatology [59, 60]. A study by Craig investigated 30 cases of idiopathic anaphylaxis and found clonal mast cell disease in 47% of them [61].

When interpreting food allergies in patients with SM, general diagnostic difficulties of food allergies should be also acknowledged [54]. During diagnostics, particular emphasis should be placed on the patient’s medical history as a positive result in additional tests such as sIgE or SPT is not associated with a clinical response to a specific allergen. This can lead to the misguided implementation of elimination diets, resulting in nutritional deficiencies. While gathering medical history, questions about the presence of cofactors in reactions, such as physical effort, alcohol, infections, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, should be asked as these factors can lower the threshold for reaction occurrence. Additionally, cross-reactivity between pollen and food could result in positive diagnostic test results without clinical implications. Skin test results may be falsely negative due to the absence of appropriate allergens in the allergen extract used for testing or when the examined reactions are not mediated by IgE [54]. What is more, spontaneous degranulation of mast cells may be mistakenly associated with food intake. These challenges necessitate extended diagnostics, including molecular diagnostics [54] and basophil activation tests [61].

It should also be noted that, due to the high risk of anaphylaxis, in most centres oral provocation/challenge tests are not conducted. Recently, a large study about safety of food and drug oral challenge tests (OCT) in patients with SM, has been published [17]. In a group of 83 patients with SM suspected of drug or food hypersensitivity, 445 OCT were performed, with anaphylaxis occurring in only 10 patients representing 2.2% of the study population. OCT with food led to 6 episodes of anaphylaxis (2.1%), 25 objective symptoms (9.1%), and 101 subjective symptoms (36.7%). The authors noted the severe course of anaphylaxis, following particularly the ingestion of a-gal, which has previously been reported in patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis. Due to the similar frequency of reactions to cohorts of patients without SM, the authors suggest OCT as an appropriate diagnostic tool for patients with SM; however, due to the risk of severe anaphylaxis, it should be performed with proper precautionary measures followed [62].

KNOWLEDGE GAP AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES IN MANAGEMENT OF FOOD ALLERGY IN MASTOCYTOSIS

Most of the data regarding the prevalence of food allergies are based on data self-reported by patients, which may be overestimated three to four times [63]. The lack of high-quality data results from patients mistaking adverse reactions to food for food allergies, what is confirmed by the wide variability in the prevalence of food allergies in countries where statistics from OCT and self-reported data are available. The inconsistency in existing definitions and research methodologies also contributes to data bias. Due to that, there is a need for conducting objective studies determining the frequency of food allergy based on the gold standard – oral food challenges, which require more workload and are associated with concerns about a higher risk of anaphylaxis. The guidelines also recommend regular assessment of patients (including the use of oral food challenges) already diagnosed with food allergy to evaluate the development of tolerance [64].

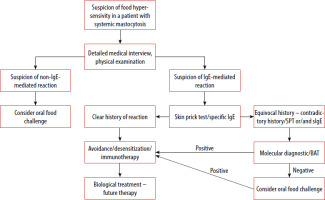

The standard treatment for food allergies is avoiding trigger foods, whereas allergen immunotherapy and biologic drugs are comparatively new methods of management [64]. There are already created guidelines regarding the use of allergen immunotherapy, including peanut, cow milk and egg allergy in the paediatric population, but these are intended only for centres with the appropriate experience [65]. Also data on the efficacy of omalizumab and etokimab, monoclonal antibodies targeting IgE and IL-33, showing a trend to a higher reaction threshold in adults with peanut allergy, have been published so far [66]. However, both allergen immunotherapy and biological treatment require further research, and the introduction of these therapeutic methods may bring benefits also to patients with SM. Figure 2 presents the suggested diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for managing food allergies in patients with SM, taking into account the aforementioned oral food challenges, as well as immunotherapy and biological treatment [67].

Figure 2

Proposal for a diagnostic-therapeutic algorithm in the case of suspicion of food hypersensitivity in patients with SM (modified based on the EAACI guidelines on the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy [67])

CONCLUSIONS

Mastocytosis is a disease with a heterogeneous clinical presentation, from mild to aggressive form, that can affect patients at all ages. Despite the rare occurrence of mastocytosis, it is important to spread knowledge about this medical condition among healthcare professionals of various specialties. Symptoms reported from the gastrointestinal tract are among the most common complaints and they contribute to a decrease in the quality of life for patients.

However, because of their nonspecific nature, they can mimic other gastrointestinal diseases. Also, due to the characteristic for this condition, i.e. proliferation of mast cells, which are mediators of allergic reactions, patients are at an increased risk of severe allergic reactions. An increased frequency of food allergies has not been demonstrated in patients with mastocytosis so far. Nevertheless, they require special caution and sometimes alternative diagnostic methods during the diagnostic process.