Introduction

Pediatric feeding disorders (PFDs) refer to the impaired consumption of food that is inappropriate for a child’s age group. These disorders can manifest as food aversion, overselectivity, sensory-motor deficits in chewing or swallowing, atypical eating patterns, and grazing [1, 2].

The prevalence of feeding disorders in children residing in the United States is estimated to be between 32.91 and 34.73 per 1000 child-years for those covered by public insurance, while for those with private insurance, the incidence is reported to be 21.07 per 1000 child-years [3], and its prevalence increases to 80% in children with some form of developmental delay [4].

PFDs are complex and influenced by various factors, including medical conditions (such as upper gastrointestinal abnormalities, cardiorespiratory diseases, and neurodevelopmental issues), nutritional imbalances (such as malnutrition, overnutrition, and micronutrient deficiencies), feeding skills (where neurodevelopmental and neurological problems can lead to limited feeding experiences and dysfunctional skills), and psychosocial factors (encompassing developmental, mental and behavioral, social, and environmental aspects) [1].

PFDs are of significant importance due to their potential to induce stunted growth, vulnerability to chronic ailments, and even fatality [4]. As previously mentioned, the etiology of PFDs can be both organic and non-organic, necessitating a comprehensive approach to the evaluation and management of PFDs in order to comprehend the underlying cause and subsequently address it accordingly. This comprehensive approach mandates collaborative efforts among gastroenterologists, nutritionists, and psychologists [5].

Several investigations have identified certain variables that contribute to the emergence of PFDs [6, 7]. Nevertheless, conducting a thorough examination of the factors linked to PFDs through path analysis can assist healthcare professionals in evaluating these disorders with increased confidence and addressing the most crucial risk factors associated with this condition.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 500 children aged 6 months to 18 years who referred to gastroenterology and liver and child nutrition clinics. After obtaining consent, the patients were included in the study. The study was conducted in two stages: the first stage was conducted through interviewing the children’s mother and collecting information through a checklist, and the second stage was conducted qualitatively through interviews with physicians. Statistical analysis and modeling were conducted using IBM SPSS and AMOS software version 24. The socioeconomic status (SES) was determined, using 5 items – father’s education, mother’s education, father’s occupation, mother’s occupation, place of residence (city and village) – by the principal component analysis (PCA) method.

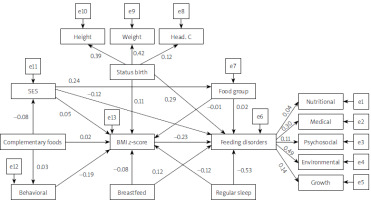

Structural equation modeling (SEM) shows the simultaneous effects of variables. This method can test the acceptance of theoretical models with data collected from different communities. The conceptual model of the study is shown in Figure 1. In the conceptual model, there are two latent variables: feeding disorders (the main dependent variable) with five indicators and birth status with three indicators. Other variables in the model are observed variables, including socio-economic status, food group, complementary feeding, exclusive breastfeeding, destructive behaviors, regular sleep and BMI z-score.

Figure 1

Conceptual model of the study

SES – socioeconomic status, Food group – average food group intake, Breastfeed – exclusive breastfeeding, Regular sleep, Behavioral – destructive behaviors, Complementary foods – start of complementary feeding, Psychosocial – psychological factors, Nutritional – nutritional factors, Environmental – environmental factors, Medical – medical condition, Growth – development, Status birth – birth status, Head. C – head circumference, Weight – birth weight, Height – birth height.

First, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted between latent variables. Then, SEM was used to evaluate the direct and indirect effects of latent and observed variables in the model on feeding disorders. To confirm the model fit, the comparative fit index (CFI) equal to or greater than 0.90, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) equal to or less than 0.08 and CMIN/DF equal to or less than 3 were applied. Model estimates were obtained using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). In all analyses, p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

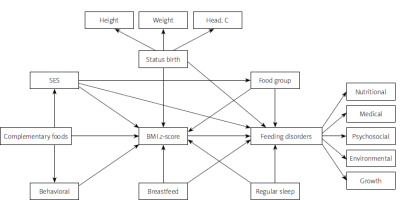

Figure 2 shows that the SES directly and indirectly plays a role in feeding disorders in children. The direct effect of SES was β = 0.042, its indirect effect was β = 0.033, and its total effect on feeding disorders was β = 0.075. According to this model, the SES increases the intake of food group and increases the BMI z-score of children with feeding disorders. Children with a higher BMI z-score had fewer feeding disorders (total effect = –0.015) (Table I).

Table I

Direct, indirect, and total effect between predictors and responses in Figure 2

Figure 2

Structural equation model of the factors affecting the feeding disorders with standard coefficients in total population (n = 496). Model fit: RMSEA = 0.060, CMIN/DF = 2.72, CFI = 0.378

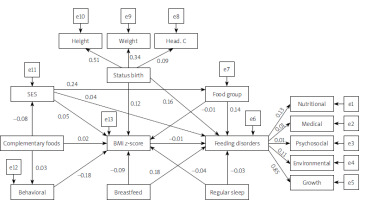

According to Figure 3, the direct effect of SES on the intake of food groups was positive (β = 0.190), on BMI z-score was positive (β = 0.100), and it was generally associated with a negative effect on feeding disorders (β = –0.05). The total effect of destructive behaviors on body mass was negative (β = 0.262) and on feeding disorders was positive (β = –0.041). Children who had regular sleep had significantly fewer feeding disorders (direct effect: –0.380, indirect effect: 0.011, total effect: –0.369). The direct effect of the BMI z-score on feeding disorders was negative; in other words, with the increase of the BMI z-score, fewer feeding disorders were observed (β = –0.157) (Table II).

Table II

Direct, indirect, and total effect between predictors and responses in Figure 3

Figure 3

Structural equation model of the factors affecting the feeding disorders with standard coefficients in girls (n = 257). Model fit: RMSEA = 0.058, CMIN/DF = 1.51, CFI = 0.960

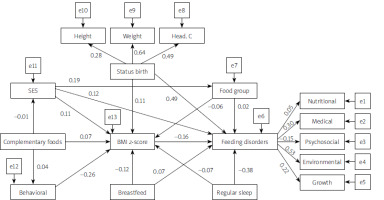

Figure 4 presents the direct, indirect and total effects of factors affecting feeding disorders in the studied boys. Similar to girls, the direct effect of the BMI z-score on eating disorders was negative in boys. In other words, with an increasing BMI z-score, fewer feeding disorders were observed (–0.386). Children who had regular sleep had significantly fewer feeding disorders (direct effect: –0.526, indirect effect: 0.027, total effect: –0.462) (Table III).

Table III

Direct, indirect, and total effect between predictors and responses in Figure 3

Discussion

Socioeconomic status (SES) plays a direct and indirect role in the development of PFD. SES encompasses factors such as parental education, parental occupation, and place of residence, including both urban and rural areas. Disparities in feeding disorder types have been observed across different socioeconomic statuses. Previous research has shown an association between lower SES, lower birth weight, and lack of breastfeeding with the occurrence of PFD [8]. Moreover, it has been proposed that a parental history of PFD may be indicative of these disorders in children. Such children without a parental history of PFD tended to have higher rates of low birth weight, more delivery complications, increased hospitalizations, greater use of prescription medications, and a higher percentage of gastrostomy tube usage [9]. However, it should be noted that some studies have not identified SES as a risk factor. For instance, Esparó et al. found that neither SES nor family characteristics contributed to PFD, but rather psychological pathologies and somatic abnormalities were associated with these disorders [10].

In this investigation, SES was associated with higher consumption of food groups and the body mass index z-score (BMI z-score) among children afflicted with feeding disorders. Children with a higher BMI z-score exhibited a reduced occurrence of nutritional disorders. These findings align with a number of analogous studies. For instance, Galai et al. found that a lower birth weight served as a contributing factor to pediatric feeding disorders (PFD), and furthermore, SES exhibited an association with both variables [8]. A different study posited that a lower SES engenders parental behaviors such as parental restriction or parental pressure, and these behaviors exert an influence on the adiposity of the child. Specifically, parental pressure increases adiposity, while parental restriction diminishes it [11, 12]. Additionally, it is postulated that the relationship between PFD in toddlers and BMI extends beyond the age range of PFD, as those diagnosed with PFD during early childhood exhibited elevated BMI levels during adolescence [13]. Nevertheless, other studies have presented contradictory results in contemporary times. The Gateshead Millennium Baby Study, a prospective cohort study, reached the conclusion that social and maternal characteristics have minimal correlations with infant weight gain [14].

The overall impact of destructive behaviors on BMI was found to be negative, while the effect on feeding disorders was found to be positive. Within the scope of this study, disruptive behaviors encompassed actions such as refusing to eat, displaying stubbornness, retaining food in the mouth, and hiding it, as well as attempting to escape from eating, exhibiting food selectivity, and expelling food from the mouth. The refusal of food as an isolated behavior represents a common experience encountered by most parents during their child’s developmental journey. The behaviors associated with food refusal in toddlers encompass whining or crying, tantrums, and spitting out food. In older children, food refusal often occurs in conjunction with other defiant behaviors, such as prolonging mealtime through conversation, attempting to negotiate food choices, leaving the table during meals, and refusing to consume an adequate amount of food in one sitting, only to immediately request food afterwards. The nutritional intake of these children primarily stems from snacks between meals [15]. According to a systematic review conducted by Saini et al., escape behavior was reported as a reinforcement mechanism for inappropriate behavior during mealtime in 92% of cases involving children with feeding disorders. This finding remained robust across various participant characteristics, including age, medical and developmental history, and referral concerns [16]. Furthermore, research has indicated that attachment styles can serve as an influencing factor in pediatric feeding disorders (PFD), with an insecure child-parent attachment potentially exacerbating PFD and contributing to malnutrition [17].

Our study revealed a significant association between regular sleep patterns and a reduced incidence of feeding disorders, with a total effect size of –0.462. Inadequate sleep appears to be a prominent clinical feature of PFDs. Altered sensory processing has been observed in both behavioral insomnia and PFD, suggesting that it may serve as an underlying explanation for the coexistence of these two conditions [18, 19]. Additionally, maternal understanding of sleep and feeding, maternal depression [20], and maternal sleep quality [21] have all been identified as potential factors that contribute to both disorders and may underlie their association with sleep.

Disordered feeding in a child is rarely limited to the child alone. An interdisciplinary team of specialists should carry out assessment and treatment. The intervention should be comprehensive and include treatment of the medical condition, behavior modification to change the child’s learned inappropriate feeding patterns, and parent education and training in appropriate parenting and feeding skills.

As a limitation of the present study, its cross-sectional nature precludes any causal inferences. Nevertheless, the findings may help build theoretical models that can be used to guide the design of longitudinal studies. The strengths of the study are the large sample size and path analysis, which shows the direct and indirect effects of the factors.

Conclusions

Socio-economic status directly and indirectly plays a role in feeding disorders in children. The direct effect of SES on the intake of food groups was positive; the overall effect of disruptive behaviors on body mass was negative and on feeding disorders was positive. Children who had regular sleep had significantly fewer feeding disorders. In girls and boys, with increasing BMI z-score values, fewer nutritional disorders were observed. This shows that examining feeding disorders in children requires a multifaceted approach. Future studies are needed to examine the strength of evidence regarding the causal nature of these factors.