INTRODUCTION

RAS is one of the most important oncogenes [1]. Its mutations occur in very dangerous cancers [2]. Developing an effective targeted small-molecule therapy against this oncogene is a major challenge. It seemed that such therapy had been developed at least in relation to RASG12C [3, 4]. Nevertheless, in patients who initially responded well to the treatment, tumor cells that were resistant to it eventually emerged [5, 6]. Therefore, it has been proposed that T cell-based immunotherapies may be more effective than small molecule therapy, despite previous beliefs that RAS neoantigens are not very immunogenic [7, 8]. However, it turns out that at least in the case of RASG12C, small molecule therapy can cooperate with immunotherapy [7].

THE ROLE OF THE RAS ONCOGENE IN ONCOLOGY

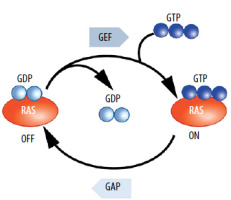

RAS (abbreviation comes from Rat sarcoma virus) mutants are among the most important oncogenes. Mutations in RAS oncogenes occur in many different types of cancer. These are oncogenes whose importance is beyond doubt. Their pro-tumor activity and mechanism of oncogenic action have been repeatedly confirmed [9]. Further research provides significant data and expands knowledge on this topic [10, 11]. RAS in its proper form, thanks to cooperation with GAPs (GTPase activating proteins), quickly hydrolyzes GTP to GDP. In the case of mutations, the hydrolysis time is extremely prolonged [12]. This causes the signals that stimulate cell proliferation or alter metabolism and come from receptors such as EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor), to be transduced for a very long time instead of being quickly interrupted [13]. These signals are transduced as long as RAS or its mutant is bound to GTP. Numerous scientific teams have provided detailed explanations for why mutations prolong hydrolysis time. Mainly, the GAP protein, arginine finger, interacts with the GTP inside the normal RAS, and thus hydrolysis is quite fast.

Mutations are observed in codons 12, 13, and 61. Mutations in codons 12 and 13 cause the channel within RAS, through which the arginine finger of GAP reaches GTP, to be covered (blocked) [14, 15]. Even changing nucleotides coding glycine to valine in the twelfth codon is sufficient to block this channel. As a result, GTP is trapped within the RAS mutants. Mutations in codon 61 also hinder the hydrolysis of GTP [16]. The pro-oncogenic activity (the function) of RAS mutants is evident. There are no doubts about their role, unlike in the case of the EGFRvIII protein [17]. This is important because in the case of immunotherapy, it is necessary for the protein that is to be targeted or is to be the basis of the attack, to play a vital role for the cancer cell, to prevent this cell from developing resistance to immunotherapy by easily eliminating the protein. RAS mutations are observed in many different types of cancer. Some of the most common cancers, where RAS mutations occur, include colon cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer, and melanoma [18]. Especially for lung and pancreatic cancer, therapies targeting these oncogenic proteins are valuable. Of course, other types of cancer can also cause very serious problems (Figure 1).

ONCOGENE RAS MUTATIONS AS A TARGET FOR SMALL-MOLECULE THERAPY

Considering the significant oncogenic role of the RAS protein and the frequent occurrence of its mutations, research on molecules that could block its oncogenic activity began quickly after the discovery of RAS. Unfortunately, RAS is a rather unconventional oncogene as was indirectly mentioned in the previous chapter. Mutations essentially cause the inactivation of its GTPase activity [19]. Therefore, it is crucial to specify exactly what is meant by RAS mutant blockers in this context. It is then a function of blockers not of its GTPase activity but more broadly of its pro-oncogenic activity, which is enhanced due to the loss of GTPase activity dependent on the GAP protein. In this situation, restoring the proper state in the cell could be related not to blocking activity that is similar to enzymatic, but to restoring the GTPase function which the RAS mutant has lost. This is not a classic situation in oncological pharmacology, where typical therapies involve blocking excessive activity, particularly the kinase activity of proteins such as EGFR or BCR-ABL (BCR comes from breakpoint cluster region protein, ABL comes from Abelson proto-oncogene) [20]. Restoring enzymatic activity would be much more difficult than blocking it.

In RAS mutant cases, blocking the oncogene’s catalysis-related function would not pass the exam. It would actually reinforce the pro-cancer effect, if at all possible, because mutations practically eliminate the GTPase activity of mutants. Due to this specificity of RAS action, for many years RAS oncogenes have been considered by some oncologists as inappropriate targets for therapy [21].

However, several other therapeutic options are currently being developed. The first one relates to restoring GTPase activity. This proves to be very challenging, and many teams are hesitant to attempt such trials. It appears, however, that these actions are not destined to fail completely. One of them is associated with a different action of the inhibitors further described below (tricomplex) [22].

Another option is blocking post-translational modifications of RAS, such as farnesylation. Without this modification, the RAS protein does not have the proper cellular localization. It should be a membrane-bound protein, but the lack of farnesylation etc., causes it to become mainly cytoplasmic and unable to transduce signals from receptors, such as EGFR. Unfortunately, farnesylation blockers have been found to be too toxic for normal cells [23]. However, currently, their use in combination with specific RASG12C blockers is being considered [24].

Further hopes rest with blockers, not of the RAS oncogene itself but of its signal transduction ability. After binding to GTP, RAS undergoes conformational changes, allowing it to interact with proteins such as BRAF (abbreviation comes from v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1) or PI3K (Phosphoinositide 3-kinases). Thus, work has begun, with some success, on small-molecule compounds that disrupt this interaction, and temporary, therapeutic successes have been achieved with this approach.

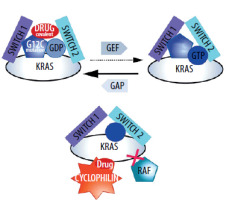

Two main projects can be described here. The first involves the creation of a so-called tricomplex. RAS proteins (with different mutants), cyclophilin, and a small-molecule inhibitor [25]. The formation of this complex means that transduction cannot occur [25]. Interestingly, the tricomplex includes a protein (cyclophilin) that has no affinity for RAS mutants or normal RAS in the absence of the tested compound [26]. In this situation, not only the molecule, but also the protein that is a part of the tricomplex (cyclophilin), is responsible for blocking transduction. The solution is interesting because, according to the developers, it is supposed to apply to different mutants of the RAS protein. The solution is not yet used in therapy [25]. As mentioned earlier, it has also been reported that the molecules forming the tricomplex not only block transduction but also restore some GTPase activity [22]. In this case, the acquisition of resistance by cancer cells is also expected for these particles [27].

The approach that has found the most application and is the most interesting from the point of view of immunotherapy (explained in the last chapter) involves creating covalent blockers of the RASG12C mutant [23].

It is commonly believed that such covalent blockers are characterized by the highest toxicity due to their potential interaction with various free cysteines.

The second approach can only be used for RASG12C. In the case of RASG12C, it was possible to design molecules that specifically and covalently bind to the RASG12C mutant [28, 29]. Their anti-cancer activity is also mainly based on disrupting the RAS–BRAF interaction.

The term “blocker” makes sense precisely in relation to such interactions. These molecules hinder the interaction with proteins downstream of RAS on signal transduction pathways, mainly because, after their binding, GEF cannot exchange GDP for GTP. The RAS conformer binding GDP cannot activate BRAF or PI3K [30].

Unfortunately, in the case of these RASG12C blockers, resistance acquisition has been observed. Various changes occur within cancer cells, from additional mutations to the activation of “bypass proteins” [31]. However, what is important from the perspective of immunotherapy, usually there are no mechanisms that involve the elimination (getting rid of by cancer cells) of the oncogenic RAS protein [32] (Figure 2).

ONCOGENE RAS MUTANTS AS A TARGET FOR IMMUNOTHERAPY

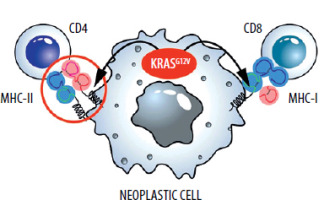

During the initial analyses, mutant RAS oncogenes did not appear to be a good target for immunotherapies. Firstly, these proteins are intracellular, so they cannot be targeted by antibodies. Currently developed technologies such as CAR-T therapy also cannot be applied in a classical form against extracellular proteins. Secondly, in the case of RAS oncogenes, single amino acid substitutions occur [33]. Usually, such changes are not very immunogenic. However, advances in immunological knowledge and the fact that we are dealing with mutations of only three RAS oncogene codons (12, 13, 61) are gradually breaking this deadlock. Namely, despite the relatively low immunogenicity, T lymphocyte clones recognizing mutated RAS epitopes presented by MHC (major histocompatibility complex) molecules are being developed and selected [34, 35].

Scientific teams are working on T-lymphocyte clones containing the corresponding TCR (T-cell receptor) molecules, even in mutants such as RASG12D [36] and RASG12V [37, 38]. In this case, the amino acid change that occurs during the mutation is minimal – an additional methyl group. Nevertheless, those T-cells arise through biotechnological manipulation, or are isolated, from naturally occurring T cells with a TCR that recognizes MHC with a peptide containing valine but not glycine (RASG12V).

Attempts to create vaccines, such as mRNA-containing RNA encoding mutants, have not been abandoned [39]. However, these efforts do not yield spectacular results. Given that these would be therapeutic and not prophylactic vaccines, and that mutations consist of changes in single amino acids, this is a very difficult challenge. Therefore, therapeutic vaccines are combined with other immunological therapies [40] (Figure 3).

COMBINATION OF IMMUNE AND SMALL-MOLECULE THERAPY

As described in the second chapter, the most effective, although only transiently in some patients, is the covalent small-molecule therapy directed against RASG12C.

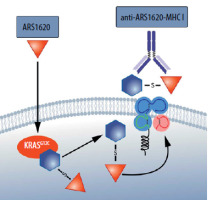

The molecules developed, bind covalently to oncogenic proteins and interrupt the signal transduction ability to and through proteins such as BRAF [41]. Meanwhile, however, the emergence of drug resistance occurs in most patients in whom this therapy has been transiently effective. Drug resistance, however, is not due to the fact that the RASG12C protein ceases to be produced in tumor cells or that it is rapidly degraded [32]. RASG12C continues to form covalent bonds with the applied molecule in resistance to therapy cancer cells. In this situation, a unique neoantigen tumor emerges [42]. RASG12C itself is also such a neoantigen, but when it binds to the covalent blocker, a new epitope, presented by the MHC, emerges that is significantly more immunogenic [43]. It turns out that it is possible to design and select not only T cells (TCRs) that can recognize such an epitope but even to obtain antibodies that will recognize the MHC together with such an epitope [42]. If so, it is conceivable in this case to create even CAR-T therapies (Figure 4).

Figure 4

The MHC molecule presents an epitope derived from RASG12C bound to a covalent inhibitor ARS 1620. Thus, there is an increase in the immunogenicity of the RASG12C mutant [42]

There are also attempts to combine known small-molecule inhibitors with PD-1/PDL1-related immunotherapies (Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1). For this study, however, the aim is to highlight the direct combination of both actions targeting the oncogenic protein itself and its epitopes [39].

CONCLUSIONS

As can be seen from the descriptions presented, immunotherapies involving the creation of T cells that recognize epitopes of mutant RAS proteins presented via the MHC molecule (mainly MHC-I), can be used in combination with small-molecule therapies. In the case of the RASG12C mutation, there is even a chance to combine immunoglobulin or CAR-T therapy with small-molecule therapy. RASG12C is a particularly interesting example.

In this case, a covalent blocker molecule binds to RASG12C, resulting in a highly immunogenic tumor neoantigen. This is an interesting approach because RASG12C signal transduction blockers are only transiently effective, and after some time, drug resistance occurs. However, due to this drug resistance, elimination of the RASG12C protein does not generally occur.

Thus, the combination of immunotherapy with small-molecule therapy offers a unique opportunity to break a deadlock. Many other RAS mutants have weaker immunogenicity than RASG12C covalently linked to a small-molecule compound, yet immunotherapies based on the selection/generation of specific TCRs are being developed. There are no small-molecule blockers, applied in clinic, for other mutants than RASG12C. However, it cannot be ruled out that they too will work in combination with immunotherapy, although, in these cases, the small-molecule compounds do not enable the generation of more potent neoantigens.