INFLAMMATION

The word “inflammation” comes from the Latin word inflammare, which means “to set on fire”. Inflammatory diseases rank among the most common disease phenomena in everyone’s life. It is a part of the body’s innate defence mechanism against infectious or non-infectious disease. Inflammation is termed as all the physiological reactions responding to the violation of the organism, which lead to the protection of the violated area from infection. Its main role is to remove damaged tissue and cells and create a suitable microenvironment for subsequent healing. At the same time, it induces changes in the organism which are helpful in these processes. An unregulated inflammatory process can become an autoaggressive process and damage to distant organs can occur, which can even cause death. Such a process is referred to as SIRS – systemic inflammatory response syndrome. The difference between inflammation as a defensive process and an autoaggressive process is in its location and regulation. The defensive process is localized and regulated whereas the autoaggressive process is unregulated and non-localized [1, 2].

Records of the formation of pus date back to the 2nd millennium BC. The first comprehensive description of inflammation was given by Aulus Cornelius Celsus, a Roman physician, encyclopedist and scientist of the 1st century AD. He described the classic symptoms of local inflammation. Dolour (pain) is caused by the presence of substances that arise in the inflammatory focus and in their action on the endings of sensitive nerves. Rubor (redness) as a manifestation of active hyperaemia, is caused by an increased amount of blood and an increased amount of hair cells. Tumour (swelling) is defined as an enlarged volume of tissue resulting from both increased blood volume and increased vascular permeability. Colour (heat) represents the temperature of the tissue affected by inflammation, which is higher compared to other tissues. Later, the German pathologist Rudolf Virch added a fifth symptom to these four basic signs of inflammation, namely lesional function (impaired function), which is associated with regressive changes in parenchymal cells. The above inflammation characteristics define inflammation from a macroscopic point of view and may not be observed to the same extent in different types of inflammation. They encompass the local manifestation of inflammatory events in tissue but do not describe the mechanism. They are the result of ongoing phenomena following the intervention of a noxious agent [3, 4].

CLASSIFICATION OF INFLAMMATION

The action of exogenous factors leads to biochemical and structural changes in cells, which are referred to as degenerative or dystrophic to necrotic changes. Exogenous inducers can be divided into microbial and non-microbial exogenous inducers (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1

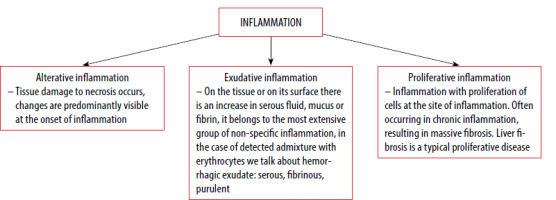

Classification of inflammation

| Time factor | Acute Chronic |

| By the cause | Infectious (viruses, bacteria, parasites) Non-infectious (trauma, atherosclerosis, frostbite) Endogenous Exogenous |

| Extent of damage | Surface Deep Bordered Unbounded |

Table 2

Classification of exogenous inducers

Endogenous inducers are signals released by tissues that are either dead, damaged, malfunctioning or stressed [5, 6].

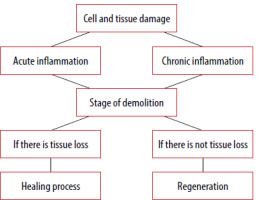

The main difference between acute and chronic inflammation is in the duration. Acute inflammation is a reaction triggered by a sudden injury to the body, such as a cut on a finger. At the site of the injury, inflammatory cells are activated by the host body, thus triggering the healing process. In chronic inflammation, inflammatory cells are continuously produced even though there is no danger [7, 8] (Figure 1). Serous inflammation presents with a relatively large amount of clear, slightly yellow, thin fluid and low protein and cellular content. A minimal increase in vascular permeability is seen, as manifested by skin blistering. Healing is by resorption. Examples of such inflammation are eczema, herpes, and catarrhal bronchitis [8, 9].

In contrast to serous inflammation, in fibrinous inflammation, large amounts of fibrin and increased vascular permeability are seen. Healing occurs through granulation tissue organization and fibrinolysis [8, 10, 11].

The pus of purulent inflammation consists of leukocytes, dead tissue and an oedematous fluid. The causative agents are S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. Healing occurs through resorption. Bounded inflammation may look like a tender mass usually surrounded by a colored area ranging from pink to deep red, which is usually referred to as an abscess [8, 12, 13].

CHRONIC INFLAMMATION

Chronic inflammatory diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide. The WHO (World Health Organization) considers any chronic disease to be the greatest threat to human health. The hallmarks of chronic inflammation are infiltrations of primary inflammatory cells such as macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells at the site of tissues that produce inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, enzymes. This contributes to the progression of tissue damage and secondary repair [7, 14–16]. Chronic inflammation can be caused by several symptoms such as failure to destroy agents causing acute inflammation. These organisms are resistant to host defence and remain in the tissue for longer periods of time. In some cases, the organism is irritated by foreign material that is impossible to destroy enzymatically. In autoimmune disorders, the body’s natural immune system recognizes the substance as a foreign antigen and attacks healthy tissue. The first phase of chronic inflammation is often inconspicuous and can be completely missed on clinical examination. Hence, chronic inflammation is divided into two groups – chronic inflammation as a consequence of acute inflammation and de novo chronic inflammation [7, 17, 18]. There are two known types of chronic inflammation. The first type is nonspecific proliferative inflammation, which is characterized by the presence of nonspecific granulation tissue formed by infiltration of mononuclear cells and proliferation of connective tissue fibroblasts. Typical diseases are, for example, a polyp in the nose, on the cervix and a lung abscess. The second type is granulomatous inflammation, a specific type of chronic inflammation characterized by the presence of various nodular damaged tissues or granulomas formed by the aggregation of macrophages [17, 18].

The etiological cause may be infectious (mycobacteria, spore-forming fungi) or non-infectious (foreign bodies). Granuloma arises when the macrophage loses its function of phagocytosis. As a consequence, macrophages lose their function; if they cannot absorb the foreign substance, there is a blockade of phagocytosis by various substances, an inborn defect of phagocytosis, long-term stimulation of T-lymphocytes. Typical diseases of granulomatous inflammation are tuberculosis – Mycobacterium tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, syphilis – Treponema pallidum, leprosy – Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium lepromatosis. Granuloma can be formed in two ways, as a result of a foreign body or an immune reaction. The second way is granuloma formed as a result of chronic infection [19, 20].

ACUTE INFLAMMATION

The main role of inflammation is to bring fluid, proteins, and cells from the blood into the infected or damaged tissue. Therefore, acute inflammation is associated with the protective entry of leukocytes, complement, antibodies, and other substances into the site of developing inflammation [5, 21]. This type of inflammation is characterised as an immediate adaptive response with limited specificity caused by multiple noxious stimuli such as infection and tissue damage. A controlled inflammatory response is generally beneficial. It provides a defence against infectious organisms. If not controlled, acute inflammation can become harmful, as in septic shock. The inflammatory pathway consists of a sequence of events involving inducers, sensors, mediators, and effectors [21–23].

The process of acute inflammation is triggered in the presence of inducers, which can be infectious organisms or non-infectious stimuli such as foreign bodies and signals from necrotic cells or damaged tissues [24, 25]. This subsequently activates sensors that are specialized molecules. In the next step, the sensors stimulate mediators, endogenous chemicals that can induce pain, activate or inhibit inflammation and tissue repair. Sensors are also involved in the activation of effectors, which are tissues and cells. The goal of the inflammatory process is to restore homeostasis regardless of the cause [24, 26, 27] (Figure 2).

PROCESSES OF INFLAMMATION

Inflammatory processes occurring at the local level consist of five steps:

Tissue damage – pathogenic factors destroy the tissue.

Recognition of damage – antigen presenting cells (APCs) (macrophages, histocytes, dendritic cells and others) recognize foreign antigens via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which are expressed on the membranes of all cells responsible for innate immunity.

Activation of immune cells in the tissue – once PRRs are activated, the cells begin to produce signalling cells that have three effects:

Destruction of damaged tissue – through cytotoxic substances, damaged tissue is removed, thus creating space for tissue regeneration or repair.

Reparation, regeneration of damaged tissue – during regeneration some tissues have preserved the ability to regenerate, provided that the extracellular components of the tissues have not been disrupted. Reparation heals the defect by scarring [28, 29].

If the inflammatory response is not required and necessary, it must be terminated to avoid the side effects of tissue damage. When this mechanism is disrupted, chronic inflammation, damage and dysfunction of multiple body systems occurs [28, 30].

SUBSTANCES RESPONSIBLE FOR INFLAMMATORY PROCESSES

The endothelium, leukocytes, platelets, coagulation system, complement are responsible for the course of the inflammatory reaction in the body. Leukocytes perform a very important signalling and regulatory function during inflammation [31].

Endothelium is a flat epithelium of mesenchymal origin lining the inner surface of the compartments of the cardiovascular system. Under physiological conditions, it is involved in the local regulation of vascular tone, providing selective permeability of the vascular wall and an antithrombotic surface. In the inflammatory process, vascular tone and permeability of the vascular wall to fluids are altered, and leukocyte attachment and migration to the interstitium are regulated. Cells have a number of receptors on their surface for mediators, tissue hormones and substances that are released by platelets [32–34].

Platelets (thrombocytes) form the primary homeostatic plug when blood vessels are damaged, and their surface provides communication with the hemocoagulation system. Platelets also contain a complex membrane system that allows them to release a variety of molecules, including adhesin molecules, growth factors, chemokines, and coagulation factors, inhibitors of blood clotting. Platelets change their shape and adhesiveness during inflammation [35–37]. After their activation, the release of granules is induced, which also contain anti-inflammatory substances. During inflammation, there is an interaction between circulating platelets and leukocytes attracted to the vessel wall by adhesion to the endothelium. As platelets adhere to the endothelium, they are able to release chemoreactants that create an adhesive surface allowing leukocyte adhesion. Platelets contain three different types of granules: alpha, delta and lambda [38–40].

Leukocytes are white blood cells, and their main function is to mediate immune responses. They are capable of movement and are involved in phagocytosis of harmful substances [41]. Leukocytes are divided into:

Neutrophils that represent the body’s first line of defence against an infectious or non-infectious agent. They can exist in a state of activation or inactivation. Neutrophil granules contain a number of enzymes capable of hydrolyzing a variety of substrates [6]. Eosinophils, which are similar in function to neutrophils, produce cytokines characterized by autocrine action [42]. Lymphocytes – their abundance is predominant in chronic or late acute inflammation [43]. Plasma cells – increased numbers are typical in persistent infections with an immune response in hypersensitivity reactions [43].

The coagulation system is used to ensure the formation of insoluble fibrin during the formation of the primary plug. In inflammation, it aids in the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. By the action of active fibrin, the individual monomers combine to form insoluble fibrin [44].

Complement is made up of 30 proteins that are part of the blood serum, but are also found on the surface of cells. Once activated, most of the proteins are cleaved into two subunits, with the smaller one providing chemotaxis of other proteins and the larger one attaching to the surface of the pathogen [45].

SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE SYNDROME (SIRS)

SIRS is an exaggerated defensive response of the body to a harmful stimulus, which can be infection, trauma, surgery or acute inflammation. It involves the release of acute phase reactants, which are direct mediators. SIRS with a suspected source of infection is called sepsis. In sepsis, if one or more end organs fail, severe sepsis is said to occur. SIRS is defined by the fulfilment of two or more of the following symptoms:

a rise/drop in body temperature above 38°C or below 36°C,

an increase in heart rate to more than the average for the age without the presence of any external stimulus, treatment, or painful stimulus,

an increase in respiratory rate to more than the average for the age,

abnormal leukocyte counts (more than 12,000/μl, or a decrease below 4,000/μl) [46].

Inflammation triggered by infectious or non-infectious stimuli elicits an immune response, but SIRS can still sometimes occur. Bone, Grodzin and Balk [47] introduced a five-stage cascade of sepsis that begins with SIRS and ends as MODS (multiple organ dysfunction syndrome):

Stage 1 is a local response at the site of injury that aims to contain the injury and limit spread.

Stage 2 is an early compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome (CARS) in an attempt to maintain immunological balance. Stimulation of growth factors and recruitment of macrophages and platelets occurs as levels of pro-inflammatory mediator decline to maintain homeostasis.

Stage 3 is when the scale tips toward pro-inflammatory SIRS, leading to progressive dysfunction. This results in end-organ microthrombosis and a progressive increase in capillary permeability, resulting in loss of circulatory integrity.

Stage 4 is characterized by CARS taking over SIRS, leading to a state of relative immunosuppression. The individual therefore becomes susceptible to secondary or nosocomial infections, thus perpetuating the sepsis cascade.

Stage 5 manifests in MODS with persistent dysregulation of both SIRS and CARS responses [47].

CHANGES IN BODY FUNCTIONS DURING THE SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE

Systematic inflammatory response consists of three phases, where the first phase involves counteracting the stimulus with released cytokines, through which an inflammatory response is initiated in order to remove the damaged tissue and subsequently repair it. In the second phase, circulating cytokines ensure the release of growth factors, the influx of macrophages and platelets, and the control of the intensity and extent of the inflammatory process – an attempt to maintain homeostasis. The final third phase is when homeostasis has failed to be restored, a significant systemic response occurs and cytokines are destructive [48–50].

TNF-α and IL-1 are involved in the development of fever, acting on the thermoregulatory centre in the hypothalamus. This leads to a higher setting and thermoregulation is maintained at the new level until the level of fever-causing substances in the body drops [51, 52]. Reduced blood pressure is due to a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance, partly due to inflammatory cytokines [53].

IMMUNOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE

Pain is an essential part of our body, because the body’s alerting to events that are taking place within it. It alerts that a certain part of the body needs extra care. Other factors such as temperature, redness and swelling are also very important because they allow the immune system to start fighting foreign substances. The dilation of capillaries and increased blood flow brings immune cells, such as neutrophils and monocytes, to the affected area. These cells fight the agents of inflammation and try to get them out of the body by using the wounds in the skin [54].

The sensation of heat is caused by increased blood movement in the dilated blood vessels to the environmentally cooled extremities. This reaction will also lead to redness due to an increase in the number of erythrocytes passing through the injured area [55, 56]. Swelling of the area occurs because of an increase in the permeability and dilation of the blood vessels. Pain is caused by an increase in pain mediators, either as a result of direct damage or as a result of the inflammatory reaction itself. Loss of function occurs either as a result of simple loss of mobility due to oedema or pain or replacement of cells by scar tissue [55, 57].

ADVANCES IN RESEARCH ON THE IMPACT OF INFLAMMATION

In recent decades, leading research has been conducted linking the mechanisms of the inflammatory system to various diseases or conditions. In the past, inflammation has been studied more from the perspective of immune cells and inflammatory mediators; however, in recent decades, more multidisciplinary and integrative approaches have been involved in the impact of the inflammatory response. This is the situation of studies that have discussed and investigated diseases and mechanisms from a different perspective.

Low-grade chronic inflammation during aging (without infection) has been shown to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality in the aging population. This is a cyclical relationship between chronic inflammation and the development of diseases (cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, cancer, frailty) associated with advancing age [58]. Within the new starting points, it is hypothesized that by linking immune dysfunction in inflammatory pathways and the aging process, the forces of chronic inflammation may be ideal targets to address aging with high translational potential. Studies targeting the immune system have tremendous potential to cause a major breakthrough in longevity research and treatment, by strengthening and targeting the immune system and eliminating senescent cells [58–61].

Inflammation is also frequently associated with depression, and inflammatory signalling pathways and their mediators play an important role in depression. Research suggests that anti-inflammatory medications can be used as the mainstay of treatment or as adjunctive therapy to reference antidepressants [62]. Inflammation has emerged as a key factor in depression. Patients with depression have markedly elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is likely that by modulating inflammatory pathways, brain structure remodelling and inflammatory plasticity through antidepressant treatment, symptoms of depression may be alleviated. Targeting inflammation may become an effective approach in the treatment of depression [62–65].

Research studies investigating the function of inflammation in stroke have shown positive relevance. Peripheral inflammation has been found to be a potent contributing factor to the development and progression of secondary cell death in stroke. Organs affected by inflammation in stroke include the spleen, cervical lymph nodes, thymus, bone marrow, gastrointestinal system and adrenal glands, which are likely to converge their inflammatory effects via B and T cells [66–69].

Weiss et al. [70] pointed out the involvement of histone deacetylases in the activation of proinflammatory signalling cascades and mediators in cultured macrophages. In addition, the methylation status of specific promoters was also investigated in terms of their involvement in inflammatory neuronal diseases. Teuber-Hanselmann et al. [71] reported hypermethylation of the original type of this gene in inflammatory conditions in the central nervous system. There have also been various discussions regarding the involvement of adipokines and obesity in the regulation of inflammation [72], or the influence of signalling on immunomodulatory responses of tumours [73].

CONCLUSIONS

A living organism is a system in which constant emergence and demise occur, creating equilibrium. If this balance in the organism is disturbed, either as a result of the organism’s internal environment or the external environment, a cascade of events occurs that leads to its restoration. The cascade of events is a stereotyped response that allows the organism to immediately deal with unwanted interference. Inflammation comes to the fore in the search for the causes of civilization diseases. It is a complex process consisting of several steps, the main function of which is to prevent the reproduction of pathogens in order to destroy them. It is caused by the secretion of substances that cause redness, swelling or pain. The most common sign of inflammation is the dilation of blood vessels, which serves as a marker of the site of infection for other leukocytes. In clinical practice, it is important to pay close attention to inflammation, and it is essential to perform appropriate investigations and to proceed to hospitalization in case of ambiguity.