INTRODUCTION

Progressive cognitive disorders with a pathological gait pattern, especially when fluctuating, are not always caused primarily by neurodegenerative diseases. Nevertheless, genetically inherited metabolic disorders, particularly in adults, are often overlooked in differential diagnoses.

Hyperammonemia is a state of increased level of ammonia in the blood serum, which is associated with its toxic effects on the central nervous system. The accumulation of toxic ammonia is most often secondary to other diseases, especially as a result of liver damage [1]. Rare causes are primary disorders of the urea cycle, with deficiency of the pathway of enzymatic reactions that convert ammonia into less toxic urea excreted in the urine [2]. The most common form of primary hyperammonemia is ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD, MIM# 311250). This hereditary disorder typically manifests in newborns or early childhood and is rarely detected in adults [3].

Patients with late-onset OTCD present nonspecific symptoms that can be triggered by various factors, including stress, infections, excessive protein intake, and certain medications such as corticosteroids [4].

Here we report a case of OTCD with a pathogenic variant c.663G>C (p.Lys221Asn) in a 60-year-old female who presented a progressive cognitive, behavioral, and gait disorders. Following the case description, we provide a literature review regarding late-onset hyperammonemia.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 60-year-old female was referred to the neurology department for further diagnosis of dementia. She had a history of Hashimoto’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Family history was unremarkable. According to the medical documentation, the first symptoms of the disease in the form of transient memory disturbances and disorientation occurred at the age of 54. She was hospitalized in the neurology department with a diagnosis of transient global amnesia (TGA). A similar episode of transient confusion occurred a year later and again the diagnosis of TGA was made, despite the fact that her cognitive and behavioral impairments had a progressive course. The patient’s family observed incidents of decreased verbal contact followed by drowsiness (lasting from a few hours to several days), difficulties in performing basic activities, and peculiar behaviors. Due to the aforementioned symptoms, at the age of 56 the patient was initially diagnosed with epilepsy (non-motor seizures), which was not confirmed. In the following years, unsuccessful attempts were made to treat her with valproic acid as the patient refused to take the medication due to “feeling unwell”. In the follow-up, psychiatrists suspected a dissociative disorder. During that time, the symptoms continued to worsen; she presented unstable, wide-base gait and cognitive decline. The patient was hospitalized four times in psychiatric wards (at the age of 58 and 59) due to psychotic disorder with hallucinations. No obvious conclusions had been drawn upon her release and only symptomatic treatment was administered.

Before her admission to our department the patient underwent several investigations: an electroencephalogram (at the age of 59) revealed an abnormal awake recording with dominant delta activity in all areas and generalized periodic slow wave theta activity; a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed several small white matter hyperintensities called “vascular lesions”, atrophy of the cerebellum and small calcifications in the basal ganglia; regional cerebral blood flow single photon emission tomography with the use of HMPAO (rCBF SPECT) showed hypoperfusion of the whole cerebellum. A panel of rheumatologic tests did not reveal any abnormalities for systemic diseases. The patient was also assessed twice using the ACE-III (Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III) scale. At the age of 56, she scored 84 points, and at the age of 60 the score was 59 points.

On the day of her admission, the patient was oriented to time, place, and herself, but mild confusion and bizarre behaviors were observed. In the neurological examination she presented with scanning speech, bilateral palmomental reflex, slightly pronounced negative myoclonus (asterixis) in the upper extremities, slight ataxia and cerebellar gait; however, she was fully mobile and independent. During her hospitalization she exhibited fluctuating levels of functioning. In the morning hours, she was usually in a good mental state; however, in the evenings she was confused and agitated.

Hematological and biochemical blood tests (including blood cell counts, electrolytes, liver and kidney parameters, glucose, C-reactive protein, vitamin B12, folic acid, copper, ceruloplasmin, antineuronal antibodies and oncological markers) did not show any abnormalities, except for an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone level (with normal thyroid hormone levels) and a level of anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibodies above the upper measurement range (> 600 IU/ml). Cerebrospinal fluid tests (cytosis, protein, glucose, Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies, venereal diseases research laboratory [VDRL], oligoclonal bands, tau and p-tau proteins, amyloid beta) were normal.

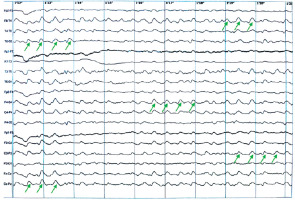

In the brain MRI, small subcortical vascular changes were visualized in both cerebral hemispheres, along with small cortical cerebellar atrophy. In the electroencephalogram (EEG), a pathological recording was again observed with numerous changes characterized by groups and series of synchronous, symmetric delta waves in both the temporal-parieto-occipital regions, superimposed on a poorly differentiated slow background activity (Figure I).

Figure I

Electroencephalogram on hospital day 2, showing a pathological recording of groups and series of synchronous, symmetric delta waves in both the temporal-parieto-occipital regions, superimposed on a poorly differentiated slow background activity. The example regions with theta waves are marked with green arrows

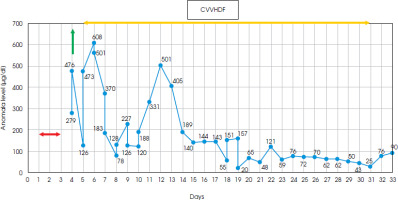

Due to a significantly elevated level of anti-TPO antibodies in the blood serum, suspicion of Hashimoto’s encephalopathy (currently known as STREAT syndrome: steroid-responsive encephalopathy in autoimmune thyroiditis) was considered as a rare cause of cognitive and motor disorders, meeting the published criteria [5]. Intravenous methylprednisolone therapy (1000 mg/day) was administered to the patient and a rapid deterioration was noticed. After 3 days of steroid treatment, there was a sudden decline in her behavior, with agitation followed by somnolence and finally coma, respiratory distress and seizures. The only notable abnormality found in laboratory tests was a significantly elevated ammonia level (279 µg/dl) in the blood serum, with no signs of liver or kidney damage (also in the abdominal ultrasound examination). Inflammatory parameters and brain computed tomography (CT) scans showed no significant changes. Generalized epileptiform activity was recorded in the EEG. Subsequent measurements showed a rapid increase in ammonia levels, reaching around 500 µg/dl, and she was referred for hemodialysis. The initial response was satisfactory, but follow-up tests revealed further fluctuations in ammonia levels. Due to the patient’s critical condition, she was transferred to the intensive care unit, where she received renal replacement therapy (CVVHDF) and respiratory support. Based on data in the literature on reported cases of corticosteroid-triggered hyperammonia, OTC mutation as a possible cause was suspected [2, 6-8]. Following the principles of hyperammonemia treatment [7, 9], the administration of sodium benzoate preparations (a 20% solution at a dose of 35 ml five times a day) and L-arginine were initiated for long-term therapy. The patient also received a low-protein, high-calorie diet. The ammonia levels fluctuated in the following days (range 20-608 µg/dl) and normalized after 18 days (Figure II). Treatment with CVVHDF was discontinued 10 days later, and the patient was transferred back to the neurology department (day 38).

Figure II

Diagram showing a timeline of the measured ammonia level, showing fluctuating range 20-608 μg/dl (normal range = 19-87 μg/dl); yellow line – a period of renal replacement therapy (CVVHDF); green line – hemodialysis; red line – administration of steroids

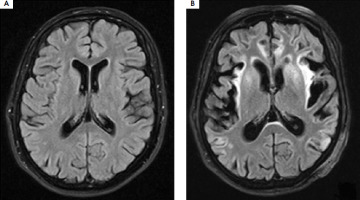

At that time, signs of metabolic damage were observed in the brain MRI (Figure III), including symmetric increased signal intensity in the cerebral cortex, subcortical white matter, and deep structures, as well as a marked loss of brain hemisphere volume. In the subsequent days of hospitalization, rehabilitation and speech therapy were conducted, and treatment with sodium benzoate and L-arginine was continued, along with adherence to dietary recommendations. The patient was alert but presented with severe apathy and fluctuations of cognitive state. Hyperammonemia requiring hemodialysis occurred twice more, likely due to a dietary error (days 86-90) and during bacterial pneumonia (days 104-117). The patient also experienced a mild case of COVID-19 infection (days 137-147), but surprisingly there was no increase in her ammonia levels.

Figure III

Brain MRI T2-weighted images performed before (A) and after (B) hospitalization in an intensive care unit with a 40-day interval shows significant loss of volume in both brain hemispheres, especially in the temporal, frontal, and parietal lobes. Scan (B) shows a widespread, fairly symmetrical increase in signal intensity in the cerebral cortex in both hemispheres, most strongly expressed in the insula, temporal lobes, and cingulate gyrus. In the areas of the insula and temporal lobes, there is an increased signal in the adjacent subcortical white matter

Diagnostic testing for congenital metabolic disorders was initiated immediately after suspicion of OTC gene mutation. Tandem mass spectrometry did not reveal any of the numerous metabolic disorders detected by this method. The urine GC-MS (urine gas chromatography-mass spectrometry) showed an elevated level of orotic acid, which is present in OTCD [10]. Blood samples were also sent for genetic testing with a negative result obtained after 2 months. However, after careful analysis repeated at our request it turned out that this examination did not cover the entire gene – 5 exons remained unexamined. Follow-up genetic testing revealed a hemizygous pathogenic variant of the OTC gene c.663G>C (p.Lys221Asn), and the patient was definitively diagnosed with OTCD. Both stages of the genetic testing were performed using Sanger DNA sequencing technology.

After 6 months of hospitalization, the patient was discharged with a recommendation for lifelong use of sodium benzoate, a low-protein diet, and arginine supplementation. At the time of her discharge, she had superficial verbal contact and could follow simple commands only. No signs of muscle weakness were observed, but she had significant postural disturbances with no ability to achieve upright positioning. Neuropsychological assessment revealed profound cognitive impairments and significant deficits in acquiring new information. Following discharge, she was referred to the rehabilitation department followed by home physiotherapy, but no improvement in motor function was gained. The patient was also referred to a genetic counseling clinic. The family history was thoroughly supplemented. According to the knowledge of the patient’s husband and adult daughter, no one in the family had previously shown symptoms of OTCD. The woman had no siblings, and her parents and grandparents suffered only from cardiovascular diseases. There were no unexplained neonatal deaths in the family. The patient had one pregnancy and gave birth to a healthy daughter, who now has two daughters with no symptoms of the disease. Following recommendations, genetic testing for OTCD was also conducted on her daughter and granddaughters, which did not reveal any mutations.

DISCUSSION

Ornithine transcarbamylase is one of the enzymes of the urea cycle, as a result of which the breakdown product of proteins – ammonia – is transformed into urea, which is excreted in the urine. This enzyme catalyzes the conversion of carbamoyl phosphate and ornithine into citrulline, a deficiency of which leads to the accumulation of toxic ammonia [11].

OTCD is the most common X-linked congenital urea cycle disorder, with an estimated prevalence of one in 62,000-77,000 [11]. Based on the clinical course, different variants of the disease are distinguished – an early-onset form and a late-onset form. The type of genetic mutation affects the progression of the disease. About 50% of hemizygous males show no residual enzyme activity, which leads to hyperammonemic encephalopathy and death in the neonatal period. In cases where the enzyme retains partial activity, symptoms appear under the influence of environmental factors that promote hyperammonemia, leading to late-onset OTCD [2]. Late-onset OTCD can manifest later in childhood or even in adulthood, and due to its nonspecific symptoms, it often goes undiagnosed in adult patients. The disease primarily affects males and is fully manifested in males only because of its mode of inheritance. However, approximately 20% of females who carry the gene mutation can also present symptoms [12]. In the somatic cells of women, one of the X chromosomes undergoes random inactivation (a process known as lyonization). In some cases, uneven inactivation may occur, where a larger number of cells actively express the mutated alleles, leading to a functional deficiency of the OTC enzyme. If the proportion of the active chromosome with the mutation is significantly higher, this may result in the manifestation of symptoms of disease [8]. A mutation in the OTC gene can also occur de novo, although the frequency of such mutations is difficult to determine [6]. Considering the unremarkable family history of our patient, we can assume that her mother was an asymptomatic carrier or that the OTC gene mutation occurred de novo in this case.

OTCD is a well-described condition – by 2015, 417 mutations had been identified as responsible for the disease [11]. The severity of the disease is often linked to the genotype of the OTC gene. However, predicting the phenotype solely based on the genotype can be challenging, especially in late-onset cases. Individuals with the same genotype may experience symptoms at different ages and follow distinct clinical courses [13]. The missense mutation identified in our patient, p.Lys221Asn, was first described as a new pathogenic variant in 2006 in a study characterizing molecular defects in Korean patients with OTCD (the codon change resulting in p.Lys221Asn was c.663C>T instead of c.663C>G). In this study, the p.Lys221Asn mutation was found in a girl diagnosed at the age of 6, but there is no information about the age of onset of the first symptoms [14]. Current evidence indicates there has been no reported case of an adult with the p.Lys221Asn mutation in the literature so far. Table 1 provides a review of the documented clinical cases in adults with OTCD who are 50 years of age or older.

Table 1

The review of the reported clinical cases of OTCD in adults at the age of ≥ 50

| study | Age | Gender | Family history of metabolic disorders | past medical history | probable triggering event | presentation | Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koya et al. [1] | 52 | Female | Negative | Temporary liver injury, abnormal behavior (abusive language, aggression) | Excess protein in food (raw fish) | Vomiting, fatigue, disturbance of consciousness | c.119G>A |

| Bijvoet et al. [2] | 67 | Male | Negative | Non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) | Infection (pneumonia), steroids | Rapid deterioration, seizures, coma | c.622G>A |

| Marquetand et al. [3] | 68 | Female | No data | No data | Protein-based nutrition supplements | Acute confusion | c.995G>A |

| Cavicchi et al. [4] | 66 | Male | Negative | Hypertension, colon cancer (colectomy and oxaliplatin and capecitabine drugs) | Chemotherapy (oxaliplatin, capecitabine) | Vertigo, seizures, slurred speech, confusion, hallucinations, drowsiness, coma | c.622G>A |

| Gascon-Bayarri et al. [6] | 56 | Male | Positive | Previously healthy | Steroids | Disorientation, agitation, decreased level of consciousness | c.622G>A |

| Summar et al. [7] | 58 | Female | Positive | Asthma, cholecystectomy, appendectomy, hysterectomy, a thyroid nodule treated with radiation | Steroids | Acute confusion, an expressive aphasia with focal deficits, coma | no data |

| Klein et al. [9] | 62 | Male | Positive | Previously healthy | Unknown (fertilizers, pesticides, and sealants which contact cracked hands) | Mental slowing, refractory seizures, and coma | c.674C>T |

| Upadhyay et al. [10] | 66 | Male | No data | Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and intermittent sinusitis, anxiety and panic attacks | Steroids, antibiotics | Headache, epigastric pain, confusion | c.118C>T |

| Matsuda et al. [13] | 56 | Male | Positive | No data | No data | No data | c.119G>A |

| Choi et al. [15] | 59 | Male | No data | No data | Excess protein intake with food | Fatigue, confusion, vomiting, disorientation | Genetic analyses were not performed |

| McCormick et al. [16] | 53 | Female | Negative | Rheumatoid arthritis | Steroids | Progressive confusion, lethargy, disorientation | c.119G>A |

| Lien et al. [21] | 52 | Male | Positive | Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia | Surgery (removal of a polyp of the throat) | Confusion, ataxia, disorientation, seizures, coma | No data |

| Daijo et al. [22] | 69 | Male | Positive | Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperuricemia | Infection | Vomiting, confusion, coma | c.622G>A |

| Bogdanovic et al. [23] | 57 | Female | Negative | Post-traumatic complex partial seizures | Sodium valproate | Fluctuating confusion, amnesia, complex partial status epilepticus, coma | c.92C>T |

| Legras et al. [24] | 52 | Female | Positive | Depression | Pregnancy, diet | Headache, vomiting, confusion, coma | No data |

| Wood et al. [25] | 54 | Female | No data | Coeliac disease | Supplemental nutrition | Altered consciousness, seizure, coma | No data |

| Tsykunova et al. [26] | 65 | Female | Two deaths of male newborn in the family history | Multiple myeloma | High-dose chemotherapy, stem cell transplantation | Fever, anorexia, hyperventilation | c.77+5G>A |

Late-onset OTCD is a disorder with high variability, influenced by environmental factors [2]. Typically, the disease follows a pattern of symptom-free intervals, with episodes of life-threatening hyperammonemic crises occurring during periods of increased catabolism. Triggers for hyperammonemic crises include infections, trauma, pregnancy, mistakes in dietary protein intake, and the use of specific medications like sodium valproate or corticosteroids [15]. Symptoms of chronic low-level hyperammonemia often precede the occurrence of a crisis and are nonspecific, including difficulties in concentration, headaches, dizziness, cognitive impairment, behavioral changes, and aggression, as well as ataxia, myoclonus, and an aversion to protein consumption [10]. In our patient, corticosteroids were the probable trigger factor. A thorough history-taking revealed such temporal crises after dietary mistakes, and she also did not tolerate the valproic acid prescribed for suspected epilepsy. Female gender and late onset may be confounding factors for taking OTCD into consideration, as well as clinical features and laboratory findings of elevated anti-TPO antibodies in a person with euthyreosis and history of Hashimoto thyroid disease.

Glucocorticoids induce a general catabolic effect, increasing protein turnover, which leads to the release of endogenous nitrogen [4]. Based on the available research, there are at least 9 reported cases indicating that the administration of glucocorticoids may precede acute hyperammonemia in individuals with OTCD [2, 4, 6-8, 16-19], where 4 cases involved patients over the age of 50 [2, 6, 7, 16]. Gascon-Bayarri et al. [6] reported a previously healthy 56-year-old man who presented with acute encephalopathy 4 days after a steroid injection to treat knee arthritis. Summar et al. [7] described the case of a 58-year-old female with a medical history of asthma who experienced acute confusion and aphasia 5 days after receiving intravenous steroid treatment, which rapidly progressed to a state of complete coma. Bijvoet et al. [2] presented the case of a 67-year-old man diagnosed with non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) who received corticosteroid therapy for the first time. One week later, he developed respiratory distress and generalized seizures, and acute hyperammonemia eventually led to his death. McCormick et al. [16] reported the case of a 53-year-old woman who developed hyperammonemic encephalopathy (progressive confusion, lethargy and disorientation) after 3 weeks of oral prednisone use for rheumatoid arthritis. Treatment included hemodialysis, ammonia-scavenging agents, and a low-protein, high-caloric diet, resulting in clinical improvement.

In addition to glucocorticoids, valproic acid and haloperidol are among the medications that can trigger a hyperammonemic crisis in individuals with OTCD, due to their toxic effects on hepatic mitochondria and inhibition of enzyme activity in the urea cycle [8]. Chemotherapeutic drugs also belong to substances that cause liver toxicity and affect protein catabolism. This may result in hindering the absorption of dietary proteins, which in turn accelerates the breakdown of endogenous proteins [4].

The aim of therapy in patients with OTCD is to maintain a normal concentration of blood ammonia. It is important not to delay treatment during the acute phase as the prognosis is strongly influenced by the duration of coma and peak ammonia levels [2]. Hemodialysis is the recommended approach for managing hyperammonemic crises and should be initiated promptly when there is a rapid rise in ammonia levels or when they exceed the range of 350-400 µmol/l [19]. It is crucial to stop protein consumption and provide an adequate number of calories to prevent catabolism. This can be achieved by administering a 10% glucose solution and intralipids. Nitrogen scavengers, such as sodium phenylacetate, sodium benzoate, or sodium phenylbutyrate are also used to reduce ammonia levels. Enhancing ammonia excretion can be achieved through the supplementation of L-arginine, L-citrulline, and L-carnitine. While liver transplantation is the only curative treatment option, it is infrequently performed in clinical practice [7, 20]. Chronic treatment involves avoiding triggers of hyperammonemia, lifelong adherence to a special low-protein diet, the use of ammonia scavengers, and arginine/citrulline supplementation [2].

CONCLUSIONS

Metabolic and inherited disorders, among others such as OTCD, should be taken into consideration in differential diagnosis even in late onset cases of cognitive impairment (especially with fluctuations) and gait disorder. It is reasonable to determine the level of ammonia in the serum in patients with non-specific symptoms, as hyperammonemia can cause permanent brain damage, lifelong disability and potentially fatal consequences.