TREATMENT OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA WITH C1 INHIBITOR DEFICIENCY (HAE-C1INH) ATTACKS

Treatment of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency (HAE-C1INH) is based on the pathogenesis of the disease. Current therapies and investigational agents undergoing clinical trials restore the balance disrupted by C1-INH deficiency by:

replacing the deficient protein,

inhibiting enzymatic proteins such as kallikrein and activated factor XII,

blocking the bradykinin B2 receptor blocker (B2R).

On-demand treatment should be considered for all angioedema attacks, regardless of location. However, it is imperative to treat any attack that develops, or is likely to develop, in the airway to avoid serious complications. Treatment should be administered as soon as possible to accelerate symptom resolution and reduce severity. Treatment is not recommended for prodromal symptoms alone, as these do not always lead to the development of angioedema. Medications should be administered at full doses, as dose reduction may weaken the therapeutic effect. These recommendations apply to patients with C1-INH-HAE/HAE-C1INH; diagnostic and treatment guidance for HAE with normal C1-INH – including on-demand, short-term, and long-term prophylaxis – is addressed in separate international consensus guidelines [1].

FIRST-LINE MEDICATIONS [2]

Replacement of the deficient protein (C1-INH) or use of a bradykinin B2 receptor blocker (B2R) is used to treat HAE-C1INH attacks.

Plasma-derived C1-INH (pdC1-INH; Berinert®) is administered intravenously at a dose of 20 IU/kg body weight. It is fast-acting and has a high safety profile, including in pregnant and breastfeeding women [3]. Cinryze® is also available, but it is not currently reimbursed in Poland.

Recombinant C1-INH (rhC1-INH; Ruconest®) is administered intravenously at a dose of 50 IU/kg body weight up to a maximum of 4,200 U. For patients weighing up to 84 kg, the dose is calculated as 50 U/kg body weight (solution volume in ml = body weight in kg÷3). For patients over 84 kg, a fixed dose of 4,200 U is given (two vials of 2,100 U each). RhC1-INH is contraindicated in patients with a known allergy to rabbit proteins. If the clinical response is insufficient, an additional dose may be given, not exceeding 4,200 U in total. No more than two doses should be administered within a 24-hour period [4].

Icatibant (several generics currently available) is administered subcutaneously at a dose of 30 mg (3 ml). If the effect is insufficient, the same dose of the drug can be given again after at least 6 hours. A patient can receive up to 3 doses of icatibant in 24 hours. In lactating women, a break in breastfeeding is recommended for 12 hours after administration of the drug. In pregnancy, the drug should only be used if the benefits outweigh the potential risks to the fetus [5].

Ecallantide is a kallikrein inhibitor, used in the USA but not approved in Europe [2].

ALTERNATIVES IN THE ABSENCE OF FIRST-LINE DRUGS

In situations where the above-mentioned drugs are not available, the administration of two units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) may be considered. However, it should be remembered that FFP may paradoxically exacerbate attacks because it contains bradykinin precursors, so its use requires caution and individual clinical assessment.

EMERGING OPTIONS IN ON-DEMAND THERAPY

Sebetralstat is an oral plasma kallikrein inhibitor indicated for the on-demand treatment of HAE attacks. Available as an orodispersible tablet, it enables early self-administration at the onset of symptoms. In clinical trials, sebetralstat significantly reduced time to symptom relief and was well tolerated [6]. The drug is approved for use in patients aged 12 years and older in the United States [7]. In Europe, it is not yet authorized, but regulatory approval is anticipated. Ongoing studies are also evaluating its use in pediatric patients from 2 years of age (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05396105).

TREATMENT OF ABDOMINAL ATTACKS

Abdominal attacks can cause severe pain, nausea, vomiting, and symptoms suggestive of an acute abdomen. They are treated with symptomatic management, including:

Efforts should also be made to identify the causative agent and, if possible, eliminate it (e.g., by eradication of Helicobacter pylori).

PRINCIPLES FOR MANAGING LIFE-THREATENING ATTACKS

Airway swelling requires immediate drug administration; however, the edema may continue to progress, potentially leading to complete airway obstruction. Therefore, patients should be placed under immediate medical supervision in a specialized center, where intubation or tracheotomy may be necessary in critical cases [2].

PATIENT EDUCATION AND ACCESS TO TREATMENT

Individuals diagnosed with HAE-C1INH should be trained to self-administer their on-demand medication [5]. Each patient should have a supply of medication sufficient to fully treat at least two episodes of edema. For patients receiving plasma-derived products, vaccination against hepatitis A and B should be considered if not previously completed [2, 3]. Additionally, influenza and COVID-19 vaccination should be considered for all patients [2].

HOME TREATMENT

Self-administration of on-demand medication is crucial to effective treatment. It allows rapid initiation of therapy, reducing symptom severity, shortening attack duration, and lowering the risk of complications. Properly managed home treatment significantly reduces the individual and social burden of the disease [8–12]. Patients should receive regular training in the correct use of self-administered medication. Approval for self-administration is governed by the Summary of Product Characteristics for each medicine.

LONG-TERM PROPHYLAXIS OF HAE-C1INH

Long-term prophylaxis (LTP) relies on the regular use of medication to reduce the frequency and severity of attacks in patients with HAE-C1INH. This helps reduce the indirect consequences of the disease, such as impaired quality of life, missed work or school, and increased use of healthcare resources due to severe and frequent attacks requiring unplanned hospital or outpatient care. Modern therapies can provide complete disease control, enabling patients to normalize daily functioning – the primary goal of long-term prophylaxis [2].

The decision to initiate LTP should be made by a physician with experience in treating HAE-C1INH, taking into account the patient’s individual circumstances and current health status [13, 14]. Several factors should be considered when qualifying a patient for LTP, including the frequency, severity, and location of HAE attacks; the impact of the disease on work and social life; the effectiveness of previous on-demand treatment; the availability of emergency care (e.g., nearest hospital, 24-hour access); and patient preference. Patients should be reassessed at each follow-up visit, and at least annually.

Before starting LTP, it should be ensured that potential triggers or aggravating factors – such as the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or exogenous estrogens – have been identified and eliminated. It should also be confirmed that the patient (or their caregiver) is actively cooperating with the healthcare team, which is crucial to effective therapy. Due to the variable course of the disease, patients on LTP should be regularly monitored for disease control, its impact on daily functioning, and potential side effects of the therapy. For this purpose, validated disease assessment tools should be used, such as the Angioedema Activity Score (AAS), HAE Activity Score (HAE-AS), HAE Quality of Life questionnaire (HAE-QoL) or the Angioedema Control Test (AECT) [2]. Patients should also keep an attack diary, as this allows better assessment of disease course, optimization of dosage, and selection of appropriate therapies, which may improve treatment effectiveness. Additionally, since attacks may still occur despite LTP, patients should have access to medications that can terminate angioedema episode [13–19].

DRUGS RECOMMENDED FOR LONG-TERM PROPHYLAXIS

First-line LTP includes four drugs, listed alphabetically: berotralstat, garadacimab, lanadelumab, and plasma-derived C1INH (pdC1-INH). Their relative efficacy and safety profiles have recently been compared in a comprehensive network meta-analysis [20] which confirmed high efficacy of all four agents in reducing attack frequency.

Lanadelumab (Takhzyro®) is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks active plasma kallikrein, reducing bradykinin production and thereby decreasing the frequency of angioedema attacks. The drug is administered subcutaneously at a dose of 300 mg every 2 weeks. If disease control is achieved, the dosing interval may be extended to every 4 weeks. In children, the dose is adjusted according to body weight. The efficacy of lanadelumab has been confirmed in randomized clinical trials and real-world evidence studies, including in the Polish patient population. Lanadelumab is approved for use in adults and children aged 2 years and older [21–23]. It is reimbursed under Drug Program B.122. According to the program’s provisions, since January 2025, treatment has been available to patients aged 12 years and older with a diagnosis of HAE-C1INH, who have experienced at least 6 severe attacks requiring rescue medication within the past 6 months.

Plasma-derived C1-INH (Berinert®) is administered subcutaneously twice weekly at a dose of 60 IU/kg body weight. It provides stable levels of C1-INH functional activity, reducing the frequency of attacks and significantly improving quality of life [19, 24–26]. It is preferred in pregnant and lactating women, as it has not been shown to harm the fetus. It is not currently reimbursed in Poland. Cinryze®, the intravenous formulation of plasma-derived C1-INH, is authorized for use by the European Medicines Agency. It is currently not reimbursed in Poland.

Berotralstat (Orladeyo®) is the first oral plasma kallikrein inhibitor, taken once daily at a dose of 150 mg with food. It may cause gastrointestinal side effects (abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea), which usually resolve with continued use. Use of berotralstat is not recommended in patients with severe hepatic or renal impairment, or in those at risk of QT prolongation, as it may affect electrocardiographic parameters. Inhibitors of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) may reduce the metabolism of the drug and impact its safety profile [27–29]. It is currently not reimbursed in Poland.

Garadacimab (Andembry®) is a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits activated factor XII (FXIIa), a key initiator of the kallikrein–kinin cascade. It is administered subcutaneously once monthly at a dose of 200 mg, following an initial loading dose of 400 mg. Studies have demonstrated an 87% reduction in attack frequency, with 62% of patients remaining completely angioedema-free after 6 months of therapy. The drug has a favorable safety profile, as it does not increase the risk of bleeding or thromboembolic events, supporting FXIIa inhibition as a safe preventive strategy in HAE [30, 31]. It is currently not reimbursed in Poland.

ALTERNATIVE OPTIONS FOR LONG-TERM PROPHYLAXIS

In the absence of access to first-line therapy, androgens or antifibrinolytic agents (used off-label) may be considered; however, their use is associated with significant limitations.

Androgens (e.g., danazol) are effective in reducing attack frequency, but their use is associated with several important limitations. The drug may cause numerous interactions (e.g., with statins or antidepressants) and adverse effects, including weight gain, fatigue, lipid abnormalities, elevated liver enzymes, and acne. In women, virilization and menstrual irregularities may occur. In men, long-term use of attenuated androgens may lead to oligospermia, testicular atrophy, and reduced fertility [32, 33]. A rare but serious complication of androgen use is hepatocellular carcinoma [34–36]. Use of these drugs is not recommended in children, or in pregnant or breastfeeding women [37, 38]. During long-term therapy, regular monitoring is essential and should include: abdominal ultrasound, complete blood count, lipid profile, α-fetoprotein levels, urinalysis, and monitoring of body weight and blood pressure [2, 34]. The effective dose of danazol may vary considerably among individuals; therefore, the lowest dose that ensures symptom control should be used. Chronic use of danazol at doses exceeding 200 mg per day is not recommended [2].

Antifibrinolytics (e.g., tranexamic acid – Exacyl®) have limited efficacy in the long-term prophylaxis of HAE-C1INH and are not recommended as standard therapy. In clinical practice, they are rarely used – primarily in children – when other drugs are unavailable or contraindicated [39]. Tranexamic acid is administered orally at a dose of 30–50 mg/kg body weight, divided into two or three doses, with a maximum daily dose of 6 g [2, 40, 41]. Adverse effects, which are usually mild, include gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea and diarrhea), fatigue, and an increased risk of thromboembolic events. Due to this risk, the drug is not recommended for patients with a predisposition to thrombosis or a history of thromboembolic events.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND INVESTIGATIONAL THERAPIES

Several novel therapeutic agents for long-term prophylaxis are under evaluation in advanced clinical trials and may significantly expand future treatment strategies for HAE-C1INH. Regulatory approvals of some of these agents are anticipated, and once available, they are expected to become first-line options in their respective indications (on-demand treatment or LTP).

These include:

Navenibart (formerly STAR–0215) is a highly selective, long-acting monoclonal antibody inhibitor of plasma kallikrein developed for long-term prophylaxis. In phase II studies, navenibart significantly reduced attack frequency and showed a favorable safety profile [42]. Compared with lanadelumab, navenibart allows a substantially less frequent dosing interval (every 3 months vs. every 2–4 weeks), due to its extended half-life. A global phase III trial is ongoing to assess its efficacy and safety (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05726325).

Deucrictibant is an oral bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist evaluated in extended-release formulation for long-term prophylaxis and in immediate-release formulation for on-demand treatment of HAE attacks. In a phase II clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05047185), daily dosing reduced monthly attack rates by approximately 80% compared with placebo and improved health-related quality of life. The treatment was well tolerated [43]. A phase III trial investigating an extended-release tablet formulation administered once daily is in progress in patients aged 12 years and older (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06669754).

In parallel, deucrictibant is also being investigated as an immediate-release oral formulation for on-demand treatment of HAE attacks in the phase III RAPIDe trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04618211).

Donidalorsen is a ligand-conjugated antisense oligonucleotide that targets prekallikrein production. It is administered subcutaneously. For long-term prophylaxis of HAE attacks, it has shown durable efficacy and a favorable safety profile. In phase II studies (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04030598 and NCT04307381), subcutaneous dosing every 4 or 8 weeks resulted in a sustained reduction in monthly attack rates by up to ~90–96%, with no new safety concerns after two years of treatment [44]. A phase III randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing efficacy and safety is ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05139810).

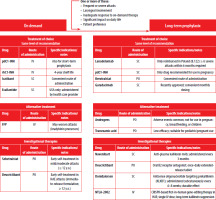

CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing therapy (NTLA-2002) is an investigational in vivo CRISPR-based approach designed for lifelong prevention of HAE attacks after a single intravenous dose. It targets the KLKB1 gene to suppress kallikrein production. In early-phase clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05120830), NTLA-2002 led to sustained reductions in monthly attack rates (75–97%) and durable suppression of plasma kallikrein levels. The therapy was well tolerated, with no serious adverse events. Long-term follow-up and larger trials are underway [45]. A visual summary of therapeutic options for HAE-C1INH, including routes of administration, clinical indications, and investigational agents, is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Overview of therapeutic options for hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency (HAE-C1INH), including approved and investigational agents. The figure summarizes indications, routes of administration, and clinical considerations to assist in treatment selection. Criteria for initiating long-term prophylaxis are listed at the top

SHORT-TERM PROPHYLAXIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF SHORT-TERM PROPHYLAXIS

The drug of first choice for short-term prophylaxis (STP) is pdC1-INH, which should be administered shortly before surgery – no later than 6 hours prior to its start. The recommended dose for adults is 1,000 IU (or 20 IU/kg body weight if individualized) [46–48], while 15–30 IU/kg is used in children and adolescents. Short-term prophylaxis prior to medical procedures effectively reduces the risk of angioedema attacks. Without prophylaxis, the incidence is approximately 30%, but drops to 9% with pdC1-INH [37]. When pdC1-INH is unavailable, FFP may be used. It is administered at a dose of two units in adults, and 10 ml/kg body weight in children, 1 to 2 hours before surgery.

The use of recombinant C1-INH (rhC1-INH) for preoperative prophylaxis has been described in the literature but is not approved for this indication [49]. Androgens and antifibrinolytics are not recommended due to their limited efficacy and the need for several days of pretreatment before surgery [47]. No specific guidelines exist for short-term prophylaxis in patients receiving long-term prophylaxis. Currently, the same preoperative prophylaxis principles are recommended as for other patients [2, 50].

MANAGEMENT DURING AND AFTER THE PROCEDURE

An angioedema attack may be triggered by any medical procedure involving mechanical trauma. This is particularly relevant for craniofacial and upper airway procedures – such as dental procedures, tonsillectomy, gastrointestinal or respiratory endoscopy, and intubation – as they increase the risk of pharyngeal or laryngeal edema. Angioedema may also impair wound management and postoperative healing [46, 47, 51, 52]. It may occur both at the surgical site and in distant locations unrelated to the procedure [53]. In most cases, symptoms develop late – typically after 8 to 12 hours – with 75% of patients affected within the first 24 hours [46]. Therefore, monitoring for at least 24 hours post-procedure is recommended.

OTHER INDICATIONS FOR SHORT-TERM PROPHYLAXIS

Short-term prophylaxis should also be considered in other high-risk situations, such as severe stress, intense physical exertion, or travel, which may trigger HAE attacks [2, 54]. Stress and other risk factors are well-documented triggers of attacks in many patients [55, 56]. Administering plasma-derived C1-INH at a dose of 1,000 IU prior to such situations may significantly reduce the risk of an attack [19, 57].

CHOICE OF THE ANESTHETIC TECHNIQUE

To minimize the risk of airway trauma, local anesthesia is preferred over general anesthesia, and a laryngeal mask is favored over endotracheal intubation [58]. If intubation is necessary, techniques that minimize mechanical trauma should be employed – such as nasal intubation, gentle induction of anesthesia, continuous monitoring, and appropriate adjustment of the endotracheal cuff pressure [59]. The use of short-acting sedation for extubation is also recommended [60]. However, none of these methods has been sufficiently validated to allow a firm recommendation. In cases of upper airway angioedema, oral manipulation should be avoided, and if intubation is required, video laryngoscopy via the nasal route is preferred [61].

POSTOPERATIVE OBSERVATION

After surgery, the patient should be monitored in the recovery room for at least 1 hour and hospitalized for a minimum of 24 hours [47]. Regardless of the short-term prophylaxis used, patients should carry rescue medication sufficient to treat at least two attacks, due to the risk of breakthrough angioedema [47, 52, 62]. Medical staff should be informed that standard treatments for angioedema, such as corticosteroids, antihistamines, and epinephrine, are ineffective in HAE-C1INH-related cases [2].

SPECIFIC RECOMMENDATIONS: DENTAL PROCEDURES

Both patients and dentists often avoid oral decontamination procedures due to safety concerns. However, chronic inflammation increases the risk of swelling, so elimination of sources of infection is recommended. Appropriate prophylaxis should be implemented before surgery to increase patient safety [54, 63]. Additional recommendations include:

SPECIFIC RECOMMENDATIONS: CARDIAC SURGERY

During extracorporeal circulation, the kinin system is activated, which may lead to significant C1-INH loss. Therefore, patients with HAE-C1INH should receive effective pdC1-INH supplementation before surgery. In addition, reducing intraoperative blood loss, ultrafiltration during surgery to minimize C1-INH loss, and standard thromboprophylaxis are recommended. Depending on the extent of surgery and patient-specific risk factors, additional dosing of pdC1-INH should be considered. If pdC1-INH is unavailable, FFP administration should be considered during surgery [65, 66]. In patients with HAE-C1INH, medications that affect the kinin system – commonly used in cardiology – should be avoided if contraindicated (see Part I for details) [67].

DISCREPANCIES BETWEEN CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS AND REIMBURSEMENT CONDITIONS

The recommendations for treatment and short-term prophylaxis presented in this document are based on current medical knowledge and clinical practice. They include the treatment of mild attacks and short-term prophylaxis in high-risk situations, such as severe stress, travel, or intense physical exertion. However, reimbursement for these therapies is limited to narrowly defined scenarios. Currently, in Poland, only the treatment of acute, life-threatening HAE-C1INH attacks – particularly those involving the pharynx, larynx, or abdominal cavity – is reimbursed. In addition, short-term prophylaxis is reimbursed only for pre-procedural prevention (e.g., before dental procedures, surgery, or certain diagnostic interventions).

SPECIFIC ASPECTS OF DIAGNOSIS AND THERAPY IN CHILDREN WITH HAE-C1INH

SPECIFICITY OF SYMPTOMS IN CHILDREN

The first symptoms typically appear between the ages of 5 and 11 and tend to increase in frequency during adolescence [57]. Isolated cases of angioedema have been reported in younger children, including a 4-week-old infant – the youngest symptomatic patient described in the literature [68]. Erythema marginatum is significantly more common in children than in adults. It may appear independently or precede the onset of angioedema. As a prodromal symptom, it is often misdiagnosed as urticaria, skin infection, or a rheumatic disease, which can delay an accurate diagnosis [68].

The most common and earliest manifestation of HAE-C1INH is peripheral limb swelling. These swellings may cause severe pain, limit mobility, and in extreme cases, lead to ischemia, impairing the child’s physical activity. Abdominal attacks are also frequent and may present with severe colicky pain, nausea, vomiting, and – if intense – dehydration. Submucosal intestinal swelling can lead to intussusception, requiring urgent diagnosis and intervention [69]. Evaluation of abdominal pain should be thorough and age-appropriate, as symptoms may mimic conditions such as acute appendicitis, testicular or ovarian torsion, mesenteric lymphadenitis, or Meckel’s diverticulitis. The most dangerous symptom of HAE is upper airway swelling, which poses a particular risk in children due to anatomical factors – narrower airways, reduced respiratory reserve, and weaker muscle tone [70]. Clinically, such an episode may resemble acute subglottic laryngitis, allergic angioedema, or foreign body aspiration. The swelling may affect not only the larynx but also the nose, pharynx, or trachea. Although more common in the second and third decades of life than in younger children, it can cause fatal asphyxiation at any age [71].

TRIGGERING FACTORS

In children, common triggers of swelling attacks include the eruption of deciduous and permanent teeth, as well as frequent mechanical trauma [72]. In girls, symptoms typically worsen during puberty due to rising estrogen levels. Smoking, which is common among adolescents, may also increase the risk of angioedema, particularly in the upper respiratory tract [57]. Early recognition of the condition is crucial, as delayed diagnosis or inadequate treatment may result in life-threatening complications – particularly in cases of laryngeal angioedema [71, 73, 74].

DIAGNOSIS

Children with a history of recurrent, isolated angioedema without co-occurring urticaria should follow the diagnostic procedures described for adults (see Part I) [57, 72]. Children of parents with HAE-C1INH should be diagnosed as early as possible. It is advisable to determine both C1-INH concentration and functional activity, even before the age of 1 year, and to repeat the test later. In healthy newborns, C1-INH levels may be slightly below the lower limit of normal. In contrast, C4 levels in infants are significantly lower than in older children and adults [57, 75].

Until HAE-C1INH is ruled out, any child of an affected parent should be considered potentially affected. Testing umbilical cord blood is not recommended due to a high risk of false-positive results. Genetic testing is not required to confirm a diagnosis of HAE-C1INH, but may be useful, particularly when a pathogenic SERPING1 mutation is known in the family, or when biochemical results are inconclusive. A positive genetic result confirms the diagnosis.

THERAPY

As in adults, pharmacological treatment is divided into three categories: (i) on-demand treatment to stop attacks; (ii) long-term prophylaxis; and (iii) short-term prophylaxis, most often used before medical procedures. The specificity of treatment in pediatric patients depends on the regulatory approvals and reimbursement status of drugs for specific age groups.

LONG-TERM PROPHYLAXIS

First-line drugs

pdC1-INH (SC): approved from 12 years of age; recommended dose: 60 IU/kg body weight,

Lanadelumab: approved for children from 2 years of age; weight-based dosing from 150 mg every 4 weeks to 300 mg every 2 weeks [76],

Berotralstat: approved from 12 years of age and ≥ 40 kg body weight; recommended dose 150 mg once daily [27],

Garadacimab: approved from 12 years of age; recommended dose: 200 mg every 4 weeks, with a loading dose of 400 mg [31].

In Poland, only lanadelumab – limited to patients aged 12 years and older – is reimbursed under Drug Program B.122.

Alternative options

The use of androgens in children is not recommended, particularly before Tanner stage V of sexual maturation [77].

SHORT-TERM PROPHYLAXIS

First-line treatment

pdC1-INH: administered intravenously at a dose of 15–30 IU/kg body weight, up to 6 hours before surgery; approved for all age groups [3].

Alternative options

As with adults, children should be encouraged to learn how to self-administer their medication, with caregiver support if necessary. This increases the patient’s sense of security and reduces the risk of complications resulting from delayed treatment. The healthcare team responsible for the patient should be provided with all relevant information about the condition and its management. Clear and accessible information should also be provided to teachers, preschool caregivers, and others caring for the child. Organizing inclusive camps and group activities can be highly beneficial. Such events enable children with HAE-C1INH to meet peers with similar conditions, learn preventive strategies, and practice self-injection techniques. As frequent infections – particularly of the upper respiratory tract – can trigger swelling attacks, full adherence to the vaccination schedule is essential. Daily physical activity does not need to be restricted. However, participation in extreme sports is not recommended [57, 77].

SPECIFIC ASPECTS OF THE MANAGEMENT OF WOMEN WITH HAE-C1INH

Although the condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, approximately 60% of all patients with HAE-C1INH are female [78, 79]. This is attributed to the greater severity and frequency of edema attacks in women, which facilitates diagnosis. This is related to the effect of estrogen on the clinical course of the disease [80]. Estrogen is one of the key triggers of HAE-C1INH; therefore, collaboration with a gynecologist is an essential part of patient care. Recurrent fluid in the pouch of Douglas and spontaneous ovarian cysts are considered characteristic findings in women with HAE. However, their direct association with the disease has not been clearly established.

Among the symptoms observed in female patients, three categories can be distinguished [80]:

Exogenous estrogen-dependent symptoms – occur only in response to synthetic hormone use (e.g., hormonal contraception or hormone replacement therapy),

Estrogen-modulated symptoms – their severity varies with endogenous hormone levels, such as during pregnancy, the menstrual cycle, or menopause,

Estrogen-independent symptoms – occur regardless of estrogen levels in the body.

The available medications and general treatment principles for women are similar to those described in earlier sections of the guidelines. Particular concern surrounds the use of attenuated androgens, which may cause significant side effects such as masculinization, hirsutism, hoarseness, deepened voice, weight gain, menstrual irregularities, pseudo-menopause, and breast atrophy [81]. Minimizing side effects is possible by using the lowest effective dose. Spironolactone (up to 200 mg/day) is sometimes recommended to alleviate symptoms of masculinization, although evidence of its effectiveness in this patient population remains limited [82, 83]. Importantly, effective contraception is essential during treatment with both androgens and spironolactone [84]. In cases of androgen intolerance, tranexamic acid may be used as a safer alternative, although its effectiveness is limited [85].

PUBERTY AND SEXUAL MATURATION

Over half of female patients (56.7%) report more frequent and severe HAE-C1INH attacks during puberty [84]. According to the PREHAEAT study, menstruation triggered attacks in 35.3% of women and ovulation in 14% [84]. Diagnosing abdominal attacks linked to the menstrual cycle can be challenging, as the symptoms often mimic those of other gynecological or gastrointestinal disorders.

PREGNANCY PLANNING

The fertility of women with HAE-C1INH is similar to that of the general population. Before conception, both the woman and her partner should be informed about the possible teratogenic effects of certain long-term prophylactic drugs and the need to discontinue them in advance. Antifibrinolytics should be discontinued a few days before conception, and attenuated androgens at least 2 months earlier. A pregnancy test is recommended prior to initiating attenuated androgen therapy to exclude an existing pregnancy. If conception occurs while taking these medications, parents should be informed of the potential risks to fetal development, particularly the effects of androgens on sexual differentiation [86].

USE OF MEDICATIONS AFFECTING REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM FUNCTION

The use of estrogens in women with HAE-C1INH may increase the frequency of attacks [81, 86], and should therefore be avoided. Synthetic progestogens with progesterone-like activity, including derivatives of normethyltestosterone, do not have this effect and may even contribute to reducing disease severity [86]. However, their combined use with attenuated androgens or tranexamic acid is not recommended, as it may increase the risk of androgenic side effects or thromboembolic complications. Barrier methods and intrauterine devices (IUDs) do not exacerbate HAE-C1INH symptoms [87]. During intrauterine insemination, gonadotropins – most commonly analogs of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) – are used to stimulate ovarian function [88]. This raises endogenous estrogen levels, thereby increasing the risk of HAE-C1INH symptom exacerbation. This creates the need for pdC1-INH prophylaxis. During in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedure, hormonal stimulation leads to an increase in estrogen levels and may raise the risk of HAE-C1INH attacks. In such cases, prophylaxis with pdC1-INH is used prior to oocyte retrieval. If ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome [88] is accompanied by angioedema, ascites, or significant hypovolemia, treatment with pdC1-INH is recommended [86].

PREGNANCY

The course of HAE-C1INH during pregnancy is unpredictable – symptoms may worsen, improve, or remain unchanged, and may vary from one pregnancy to another in the same patient [84, 86, 89]. An earlier onset of HAE-C1INH symptoms has been associated with a greater risk of more severe disease during pregnancy [90]. Worsening of symptoms is also more common in women carrying a fetus affected by HAE-C1INH [90].

The severity of attacks may fluctuate throughout pregnancy. Attacks are most likely to occur during the first trimester, when estrogen levels are increased, and during the third trimester, when elevated placental hormones with prolactogenic activity – along with mechanical factors such as fetal movements – may trigger symptoms [89–91]. Abdominal attacks also tend to be more common in the third trimester [76]. Current understanding of the course of HAE-C1INH in pregnancy is based on limited clinical data, and individual experiences may differ significantly from the patterns described above.

Diagnosing localized abdominal edema during pregnancy is particularly challenging and primarily relies on ultrasound (US) examination. Swelling of the intestinal wall or fluid accumulation in the peritoneal cavity may indicate an attack; however, in advanced pregnancy, ultrasound findings may be inconclusive. In such cases, the diagnosis is often supported by clinical improvement following administration of pdC1-INH [86].

CHILDBIRTH AND BREASTFEEDING

Childbirth in women with HAE-C1INH should take place in a hospital setting. In 80-90% of patients with HAE-C1INH, vaginal delivery occurs, and the cesarean section rate is comparable to that of the general population [84, 90]. Perinatal prophylaxis with pdC1-INH is recommended for patients with severe HAE-C1INH during pregnancy, a history of perineal attacks triggered by mechanical pressure, or planned assisted delivery (e.g., forceps) [2]. Short-term prophylaxis is also used before a scheduled cesarean section. In patients with HAE-C1INH, epidural anesthesia is preferred to avoid intubation, which may cause laryngeal edema. As in pregnancy, fresh frozen plasma can be used if pdC1-INH is unavailable [92]. Patients with HAE-C1INH require at least 72 hours’ postpartum observation [84]. An increased incidence of attacks, especially in the abdominal region, is observed during breastfeeding [90]. This increase is associated with elevated prolactin levels [93]. The drug of choice during this period is pdC1-INH. In some cases, discontinuing breastfeeding can help reduce symptom severity [86].

MENOPAUSE

Hormone replacement therapy containing estrogens or phytoestrogens should not be used [86]. Tibolone, a normethyltestosterone derivative, is well tolerated but should not be used in combination with danazol, as the cumulative androgenic effects increase the risk of adverse effects [94]. Medications that may alleviate hot flashes and insomnia include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) – especially paroxetine, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine, and centrally acting agents like clonidine [86].

NEOPLASTIC DISEASES

All approved medications for HAE-C1INH can be used in patients with breast cancer. However, caution is advised when using attenuated androgens, as available data on their safety in this patient group are conflicting. Tamoxifen may increase the frequency and severity of angioedema attacks [95]. In endometrial cancer, an estrogen-dependent malignancy, all HAE-C1INH treatments – including androgens – can be used. Similar recommendations apply to cervical cancer as well [96] (Table 1).

Table 1

A summary of treatment recommendations for patients with HAE-C1INH

MONITORING THE COURSE OF THE DISEASE. PATIENT EDUCATION. ORGANIZATION OF PATIENT CARE IN POLAND

In recent years, care and monitoring for patients with HAE-C1INH in Poland have improved significantly, leading to better treatment standards and quality of life. To provide specialized care, a network of Regional Centers for the diagnosing and treating HAE-C1INH has been established in Poland. The Main Center in Krakow coordinates these centers and supports collaboration among physicians specializing in HAE-C1INH. The Section of Hereditary Angioedema, operating within the Polish Society of Allergology, brings together physicians from reference centers and other specialists involved in caring for HAE-C1INH patients. Its primary goals are to develop clinical management standards, provide education, and foster collaboration among specialists treating HAE-C1INH. A Patients’ Association (Pięknie puchnę) also supports diagnosis and treatment, raises awareness, and educates patients and families about disease management. Regular visits – at least once a year – to a specialized HAE-C1INH center enable clinicians to monitor disease activity, assess quality of life, and check for adverse drug reactions. Patients with unstable disease, recent diagnoses, or long-term androgen treatment require more frequent follow-up visits [2]. Registering at a Regional Center ensures coordinated care, regular monitoring, and access to individualized treatment plans. Patients also receive therapeutic support and guidance for everyday living with HAE-C1INH. A detailed list of Regional and Central HAE Centers in Poland, including facility names, contact details, and locations, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Regional and Central HAE Centers in Poland

PROCEDURE FOR REGISTRATION AND INITIAL VISIT TO THE REGIONAL CENTER

Any patient diagnosed with HAE-C1INH should be registered at a Regional Center. During the first visit, the following steps will be completed:

Meet the attending physician and receive a direct contact number.

Receive an individualized treatment plan, including a diary for tracking HAE attacks and medication use.

Receive written information about reference centers and Regional Center contact details for HAE-C1INH care.

Receive a referral for intravenous drug administration.

Register with the Main Center in Kraków and receive a patient ID card [97].

Undergo initial training on HAE-C1INH, including education for the patient and caregivers about the disease, mechanisms of attacks, emergency management, proper medication use (including self-administration), and the importance of tracking attacks and treatment. This training should be documented in the medical records, along with an assessment of the patient’s understanding.

If qualified for treatment with lanadelumab (or future first-line long-term prophylaxis), receive information about the drug program requirements. This includes regular follow-up visits, instructions for storage, transport, and administration of the medication, potential side effects, and how to manage them.

If long-term treatment with danazol or tranexamic acid is needed, receive information that these medications are prescribed off-label.

REQUIRED SCOPE OF MEDICAL RECORDS FOR A PATIENT WITH HAE-C1INH

The attending physician should note the following in the documentation:

Patient identification data, including full name, address, telephone number, and contact details of a designated family member or emergency contact.

Clinical status: assessment of the patient’s current condition, including attack characteristics (frequency, severity, and anatomical location).

Family history, including information on HAE-C1INH in relatives. The physician should also inform the patient about the importance of diagnostic testing in first-degree family members.

Results of laboratory tests, including serum C1-INH concentration and functional activity, C4 complement level, and any additional tests deemed necessary by the physician.

Ongoing treatment data, including the impact of the disease on the patient’s daily functioning and quality of life. The documentation should also reflect the effectiveness of therapy during follow-up visits, with notes on attack frequency and severity, medication use, and results of patient-reported outcome measures (e.g., HAE-AS, HAE-QoL, AECT, VAS).

Patient and family education: includes discussion of the disease, treatment plan (especially for life-threatening episodes), and training in medication use and self-monitoring. The benefits of early treatment initiation during attacks, as well as the indications and principles of short-term prophylaxis before medical procedures, should also be explained.

Treatment information, including medications used and the expected frequency of attacks, which determines the number of medication packages prescribed. Informed consent must be obtained from the patient for any off-label treatment.

SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES OF FOLLOW-UP VISITS TO THE REGIONAL CENTER

Regular follow-up visits to the Regional Center are aimed to:

Continue to educate the patient – monitor their level of knowledge, remind them of the rules of life-threatening situations and self-administration of medications.

Monitor the effectiveness of therapy – assess the frequency of attacks, the effectiveness of treatment and the occurrence of side effects.

Identify side effects – assess drug tolerance and possible side effects of the therapy used.

Patient training – a reminder of the rules for the use of medications in life-threatening conditions and the rules for short-term prophylaxis before medical procedures or in other situations.

Maintain constant contact with the center – the patient should report significant changes in the course of the disease to the attending physician.

Additional training on self-administration of medications, record-keeping of medication use and handling life-threatening situations should be provided at Regional Centers as needed.

PATIENT GUIDANCE FOLLOWING THE INITIAL REGIONAL CENTER VISIT

Following the initial visit to the Regional Center, the patient should:

Know how to manage an angioedema episode, including life-threatening situations.

Always carry their medication. If the last dose is used, they should immediately contact the Regional Center or the attending physician.

Have written information about the disease and a copy of the treatment plan or prescription to facilitate rapid intervention in emergencies.

Know the location of the nearest hospital providing HAE-C1INH care and have contact information for the attending physician or Regional Center nurse.

Document each attack in a symptom diary, including its course, the dose administered, and the drug’s batch number.

If possible, learn to self-administer the medication, especially in situations where medical assistance is not immediately available.

The goal of implementing a comprehensive treatment plan for HAE-C1INH is to prevent deaths from angioedema attacks, minimize disability, and improve patients’ quality of life.

The appendices to the previous version of the Position Paper [34] include templates for the following documents: (i) Treatment Diary, (ii) Referral for intravenous drug administration, (iii) Hereditary Angioedema Patient ID Card, and (iv) Informed Consent for Off-Label Treatment.