INTRODUCTION

Since the first position paper of the hereditary angioedema (HAE) Section of the Polish Society of Allergology [1, 2] was published in 2018, more than 1,000 new scientific articles on hereditary angioedema have appeared [3]. The rapid expansion of knowledge in this field justifies updating the recommendations. The main updates include: (i) treatment, with a focus on long-term prophylaxis and the extension of approved indications for on-demand therapies to younger children; (ii) identification of new genetic mutations associated with HAE; and (iii) reclassification of HAE within the updated framework based on angioedema endotypes and subtypes. A new chapter has also been added on the perioperative management of patients with HAE-C1INH. This publication, developed with the active involvement of Section members, aims to support allergists and other healthcare professionals in managing patients with angioedema in everyday clinical practice.

Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency (HAE-C1INH) is a genetic disorder characterized by localized, self-limiting swellings of the skin and mucous membranes. These swellings result from a transient increase in vascular permeability due to excessive bradykinin production [4, 5]. The condition was first described by William Osler in 1888 [6]. Seventy-five years later, in 1963, Donaldson and Evans identified C1 inhibitor (C1INH) deficiency in the complement system as the etiological factor [7]. HAE-C1INH is caused by a mutation in one allele of the SERPING1 (serpin family G member 1) gene, which encodes C1INH. This results in decreased protein levels or reduced biological activity. The inheritance pattern is autosomal dominant, so a positive family history is usually present. However, in 20–25% of cases, the disease is caused by a de novo mutation, one arising spontaneously and not inherited from either parent [4, 5]. Hereditary angioedema is a rare disease with a prevalence estimated at 1 in 50,000 individuals in the general population [8].

CLASSIFICATION

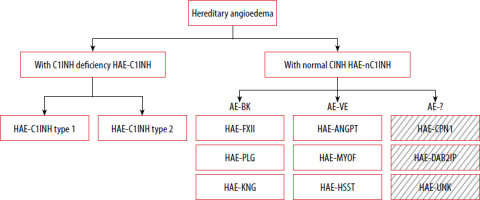

Classification of hereditary angioedema (HAE) (Figure 1)

Figure 1

Classification of HAE based on DANCE consensus. Boxes with diagonal patterns represent angioedema of unknown or uncertain/multiple mechanisms

AE-BK – bradykinin-mediated angioedema endotype, AE-VE – vascular endothelium-dependent angioedema endotype; other abbreviations – see text.

HAE with C1 inhibitor deficiency (HAE-C1INH)

Type 1 HAE-C1INH – accounts for approximately 85% of HAE-C1INH cases; associated with a quantitative (low antigenic levels) and functional deficiency of C1 inhibitor.

Type 2 HAE-C1INH – accounts for approximately 15% of cases; characterized by normal or elevated antigenic levels of C1 inhibitor with reduced functional activity.

HAE with normal C1 inhibitor levels and function (HAE-nC1INH) [9–16]:

HAE-FXII – F 12 (factor 12) gene variant,

HAE-PLG – PLG (plasminogen ) gene variant,

HAE-KNG1 – KNG1 (kininogen 1) gene variant,

HAE-ANGPT1 – ANGPT1 (angiopoietin 1) gene variant,

HAE-MYOF – MYOF (myoferlin ) gene variant,

HAE-HSST – HS3ST6 (heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfotransferase 6) gene variant,

HAE-CPN1 – CPN1 (carboxypeptidase N1 ) gene variant,

HAE-DAB2IP – DAB2IP (disabled homolog 2-interacting protein) gene variant,

HAE-UNK – unknown genetic cause.

As part of the DANCE (Definition, Acronyms, Nomenclature, and Classification of Angioedema) initiative, an international panel of experts in allergy and clinical immunology developed a classification system for angioedema that considers both clinical presentation and underlying pathophysiology [9]. The document standardizes terminology and abbreviations for the various types of angioedema. Angioedema is categorized into three endotypes based on known pathogenetic mechanisms and two subtypes, depending on whether the underlying cause has been identified.

CLASSIFICATION OF ANGIOEDEMA ACCORDING TO THE DANCE SYSTEM [9]

Endotypes of angioedema:

AE-MC (mast cell–mediated angioedema).

AE-BK (bradykinin–mediated angioedema), including both hereditary (HAE-C1INH) and acquired (AAE-C1INH) forms associated with C1 inhibitor deficiency, as well as other hereditary types such as HAE-FXII, HAE-PLG, and HAE-KNG.

AE-VE (angioedema due to intrinsic vascular endothelial dysfunction), including HAE-ANGPT1, HAE-MYOF, and HAE-HS3ST6, among others.

Subtypes of angioedema in the DANCE Classification:

Hereditary angioedema has therefore been classified within the AE-BK and AE-VE groups based on mechanistic data. However, this classification requires further validation and supporting evidence [17], particularly in light of recently identified HAE variants that do not clearly align with either endotype. HAE-CPN1 and HAE-DAB2IP, both identified after the publication of DANCE, appear to involve multiple or not yet fully understood mechanisms, making their placement within the current classification uncertain. These examples highlight the limitations of the existing endotype-based framework and support the need for its ongoing refinement. HAE-UNK refers to patients with a positive family history of angioedema in whom no causative mutation has been identified. The final common effector mechanism in all forms of angioedema is increased endothelial permeability.

PATHOGENESIS

BIOLOGICAL ROLE OF C1 INHIBITOR

C1 inhibitor (C1INH) is an acute-phase protein and a member of the serpin (serine protease inhibitor) family. It plays a key regulatory role in several proteolytic cascades, including coagulation, fibrinolysis, and the kallikrein-kinin system, particularly in the generation of bradykinin. C1INH inhibits the classical and lectin pathways of complement activation. Its mechanism of action involves direct binding to circulating proteases, including complement components C1r and C1s, mannose-binding lectin–associated serine proteases (MASP-1 and MASP-2), factor XII (Hageman factor), factor XI, and kallikrein [18, 19]. Excessive activation of factor XII and insufficient inhibition of kallikrein are the primary mechanisms responsible for clinical symptoms in HAE-C1INH. Kallikrein catalyzes the release of bradykinin from high-molecular-weight kininogen (HMWK). Bradykinin binds to the bradykinin B2 receptor (B2R), inducing increased vascular permeability and resulting in angioedema [20]. The direct molecular mechanisms that initiate angioedema attacks are not yet fully understood. A critical early event is the local activation of factor XII and prekallikrein, occurring both in plasma and on the surface of endothelial cells. Proposed triggers of FXII activation include the release of phospholipids from damaged cells [21], heat shock proteins produced in response to cellular stress [22], and heparin released from activated mast cells [23]. C1INH limits bradykinin production by inhibiting both kallikrein and FXIIa. Its deficiency leads to excessive, uncontrolled bradykinin generation, ultimately causing angioedema [23, 24].

GENETICS OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

HAE-C1INH follows an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. In most cases, patients have a positive family history, with relatives also affected. However, a positive family history is not a prerequisite for diagnosis as approximately 25% of symptomatic patients have a de novo mutation [25, 26]. Almost all patients with HAE-C1INH are heterozygotes, carrying a mutation in one allele of the SERPING1 gene located on chromosome 11. Rare homozygous cases have also been reported in the literature [27–30]. To date, more than 1,000 distinct mutations have been identified in unrelated individuals with type 1 or type 2 HAE-C1INH, and an online database of these mutations is available [31, 32]. The most common genetic alteration, found in nearly 80% of cases, is a single base-pair substitution. Less commonly, approximately 20% of patients have large structural alterations in the gene, such as partial deletions and duplications.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF HAE-C1INH

Hereditary angioedema is characterized by recurrent episodes of swelling that affect deep dermal and submucosal tissues – including subcutaneous tissue of the skin, as well as mucosal linings of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. These episodes are not accompanied by pruritus or urticarial wheals and do not respond to treatment with glucocorticosteroids (GCS), antihistamines, omalizumab, or adrenaline. Edematous lesions may also occur in the genitourinary tract [4–6]. Isolated cases of neurological symptoms, including cerebral edema, have been reported, although a causal relationship with HAE remains unconfirmed [33–35].

The disease can manifest at any age, but symptoms most commonly begin in childhood, typically between 5 and 11 years of age. Earlier onset is associated with a higher risk of a more severe disease course. Symptom severity often increases during adolescence, particularly in females [36–38]. Only a small proportion of patients – less than 5% after the age of 20 years – experience few or no symptoms [39]. The frequency and anatomical location of edematous attacks may vary substantially within the same patient over time [40].

HAE-C1INH attacks may occur spontaneously or be triggered by minor trauma, medical procedures (e.g., dental, endoscopic, or aesthetic), physical exertion, infections (e.g., urinary tract infections, Helicobacter pylori colonization), or stress. Symptom exacerbation may be associated with elevated estrogen levels, particularly during puberty and pregnancy. Exogenous estrogens (e.g., from oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy) similarly increase the frequency of angioedema episodes [41–43]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors increase local bradykinin levels and may provoke severe attacks [24]. Other medications – such as gliptins, neprilysin inhibitors, and tissue plasminogen activators – are also believed to induce bradykinin-mediated angioedema [24]. Renin inhibitors (e.g., aliskiren) and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (e.g., sirolimus, everolimus) have also been implicated in triggering bradykinin-mediated angioedema, although evidence remains limited and based primarily on case reports. The unpredictability of attacks, the chronic nature of the disease, and the potential for fatal outcomes all negatively impact quality of life [44].

PRODROMAL SYMPTOMS

Some patients experience prodromal symptoms before an attack, including irritability, headache, burning sensations in the skin, numbness, paresthesia, or erythema marginatum. Erythema marginatum – characterized by serpentine, erythematous discoloration – occurs in 42–58% of cases and may be mistaken for urticaria. These symptoms are often accompanied by fatigue and malaise [45, 46].

CUTANEOUS AND SUBCUTANEOUS SWELLING

Cutaneous and subcutaneous swelling is the most common clinical manifestation of HAE. It typically affects the face, limbs, and genitalia. These swellings are asymmetric and not accompanied by pruritus, erythema, increased skin temperature, or urticarial lesions. Angioedema develops gradually, usually over several hours, and typically lasts 48–72 h, occasionally persisting up to 5 days [4–6].

ABDOMINAL MANIFESTATIONS

Paroxysmal abdominal pain occurs in approximately 90% of patients with HAE-C1INH. In children, it is often the only manifestation, which can significantly delay diagnosis. Typical gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and varying degrees of abdominal pain, from mild discomfort to intense pain, which may mimic acute abdomen or other surgical emergencies. Imaging studies such as ultrasound or computed tomography often reveal bowel wall thickening and fluid accumulation in the retroperitoneal space. These findings, combined with vasodilation, may result in hypovolemia, hypotension, or dehydration. In severe cases, hypovolemic shock may occur [4, 5].

UPPER RESPIRATORY TRACT SYMPTOMS

Oropharyngeal and laryngeal angioedema are among the most critical manifestations of HAE as they can rapidly lead to life-threatening airway obstruction. Notably, laryngeal edema may occur without visible swelling of the face, neck, or lips as it can be confined exclusively to the mucosal surfaces of the upper airway. Because of this, clinicians and patients must remain especially vigilant: even subtle or nonspecific symptoms suggestive of upper airway involvement – such as voice changes, throat tightness, or difficulty swallowing – should prompt immediate evaluation. In some cases, isolated laryngeal edema may be present and detectable only through endoscopic examination [47]. Approximately 50% of patients with HAE experience at least one episode of laryngeal angioedema in their lifetime, and 60–70% of these individuals report recurrent episodes [48].

OTHER MANIFESTATIONS

Swelling may occasionally occur in atypical sites, including the urinary, musculoskeletal, and central nervous systems. In the urinary tract, swelling may affect the bladder or urethra, resulting in voiding disturbances and symptoms resembling renal colic. When the musculoskeletal system is involved, patients may report muscle tightness, including in the chest, and joint swelling. Central nervous system involvement may result in headaches and visual disturbances [33–35]. These atypical presentations underscore the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion in patients with recurrent, unexplained symptoms.

DIAGNOSIS

HAE-C1INH should be considered in patients presenting with characteristic symptoms, particularly after more common causes of angioedema have been excluded (see ‘Differential diagnosis’). In such cases, diagnostic testing for hereditary angioedema is warranted. The hallmark clinical features of HAE-C1INH include [24, 48]:

recurrent, asymmetric episodes of cutaneous angioedema that develop gradually over several hours, persist for 2 to 5 days, and do not respond to GCS, antihistamines, epinephrine, or to omalizumab,

recurrent episodes of abdominal pain resolving spontaneously within 1 to 3 days, particularly in patients with a history of cutaneous swelling,

any episode of laryngeal edema, even if only once.

The diagnosis of HAE is further suggested by:

a positive family history of angioedema (though not essential for diagnosis) [4, 5, 49],

early symptom onset, usually during childhood or adolescence,

prodromal symptoms preceding angioedema episodes,

absence of urticarial lesions (though their presence does not exclude the diagnosis as chronic urticaria may rarely coexist with HAE).

Clinical suspicion of HAE-C1INH should be confirmed through complement testing, including C4 levels as well as both the concentration and functional activity of C1 inhibitor. All three parameters should be evaluated, with particular emphasis on C1INH testing, which is critical for diagnosis; according to expert consensus, functional activity below 50% is considered suggestive of HAE-C1INH, with most untreated patients typically presenting with values well below 30% [49]. Serum C4 levels are most often decreased in patients with HAE-C1INH. However, the sensitivity and specificity of C4 as a marker for HAE are limited [50], it can be useful in specific clinical situations, for example when access to more specific tests is limited or in the diagnostic work-up of children with unexplained recurrent abdominal pain, particularly in the absence of typical peripheral edema, recognizing that abdominal symptoms may be the initial or only manifestation of the disease at this age. Nevertheless, complete biochemical tests are mandatory to confirm diagnosis.

Testing should be repeated after 1–3 months on a new blood sample [24, 49]. Given its diagnostic importance, careful handling of blood samples is essential. The functional activity assay of C1INH is highly sensitive to pre-analytical conditions as cooling the sample may yield falsely low results. If in doubt, laboratory results should be confirmed at a specialized HAE center. Freezing the sample is acceptable if testing cannot be performed the same day [51, 52].

Genetic testing is not routinely recommended for the diagnosis of HAE-C1INH. Identification of a pathogenic variant in the SERPING1 gene affecting C1INH level or function is not required to confirm the diagnosis, especially since no mutation is found in up to 8–10% of patients [30]. In such cases, extended analysis of intronic or untranslated regions may be informative [53]. Genetic analysis should be performed in laboratories with validated methods and expertise in variant interpretation. Genetic diagnosis may also aid in differentiating HAE-C1INH from acquired angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency (AAE-C1INH) (see below), and in selected clinical contexts, such as mosaicism [54]. In contrast, genetic testing is essential for the diagnosis of HAE with normal C1INH. The role of genetic testing in children and pregnant women is discussed in Part 2 of this Position Statement.

Interpretation of test results in patients with suspected HAE and a positive family history:

decreased C4 and C1INH concentration, along with reduced C1INH functional activity – consistent with HAE-C1INH type 1,

decreased C4 and reduced C1INH functional activity, with normal or elevated C1INH concentration – consistent with HAE-C1INH type 2,

normal C4, normal C1INH concentration and activity – HAE with normal C1INH should be suspected. In such cases, genetic testing for known mutations is recommended. As HAE-UNK is a diagnosis of exclusion, acquired forms of angioedema – which may coincidentally occur in more than one family member – should be considered in the differential diagnosis [24, 51]. In patients without a family history of angioedema, distinguishing HAE from AAE-C1INH is essential (see below).

Typical laboratory findings for HAE subtypes are summarized in Table 1 [51].

Table 1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

EXCLUSION OF MEDICAL CONDITIONS THAT ARE NOT ANGIOEDEMA

Angioedema is a paroxysmal, self-limiting, and localized swelling of the submucosal and/or subcutaneous tissues of the skin or mucous membranes, caused by a transient increase in vascular permeability [9].

Therefore, it must be distinguished from conditions in which cutaneous or mucosal lesions are persistent, progressive, or generalized. These may include [55]:

internal medical conditions (e.g., circulatory insufficiency, thyroid disease, venous stasis, infiltrative lesions such as tumors, amyloidosis, or IgG4-related disease),

dermatologic diseases (e.g., Morbihan disease) and multisystemic syndromes (e.g., Clarkson syndrome, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, Wells syndrome),

conditions presenting with abdominal symptoms (e.g., endometriosis, porphyria, acute abdomen).

EXCLUSION OF MAST CELL-MEDIATED ANGIOEDEMA

Diagnosis relies on typical triggers, characteristic clinical features, and treatment response. AE-MC is often triggered by well-defined immediate hypersensitivity causes, such as food, medications, or aeroallergens. AE- MC may occur at any age and is often associated with urticaria or anaphylaxis. Symptoms typically develop within 30 to 60 min or a few hours and resolve spontaneously within 24–48 h. A family history is usually negative [17, 56, 57]. Second-generation H1-antihistamines are typically effective and may be used at up to four times the standard dose if symptoms persist. Treatment should be continued long enough to assess its effectiveness in preventing further episodes. If symptoms persist, daily montelukast may be added [55, 58, 59]. If clinical improvement is still not observed, a 4–6-month course of omalizumab is considered appropriate [55, 60]. A favorable response to the above treatments supports a diagnosis of AE-MC.

EXCLUSION OF DRUG-INDUCED ANGIOEDEMA

As noted in the “Clinical presentation of HAE” section, several drug classes may cause angioedema through distinct IgE-independent mechanisms, including:

inhibition of kinases involved in bradykinin degradation (e.g., ACEIs, gliptins, neprilysin inhibitors) [61–64],

activation of HMWK cleavage (e.g., tissue plasminogen activators) [65, 66],

disruption of arachidonic acid metabolism (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) [67],

upregulation of bradykinin B2 receptors (e.g., estrogen-containing preparations) [68].

Angioedema has been reported in association with a wide range of medications — including commonly used agents such as paracetamol — though this does not confirm a causal relationship [69]. Drug-induced angioedema (AE-DI) is typically excluded based on symptom resolution after discontinuing the suspected agent for 1–2 months or longer, depending on attack frequency [55]. Drug-induced bradykinin-mediated angioedema typically does not respond to corticosteroids or antihistamines, supporting a non-mast cell-mediated mechanism. In patients with HAE, ACEIs are contraindicated as they may exacerbate angioedema symptoms. Among ACEIs, certain agents appear to carry a higher risk of inducing bradykinin-mediated angioedema. Specifically, ramipril and perindopril have been more frequently implicated in clinical and pharmacovigilance reports, whereas lisinopril, captopril, and cilazapril are associated with a lower incidence of such events. These differences may be related to their physicochemical properties, degree of lipophilicity, need for hepatic activation, and local tissue accumulation of active metabolites. However, further comparative studies are needed to confirm these observations [61, 62]. Estrogens, which upregulate bradykinin B2 receptor expression, may also worsen disease activity and are also contraindicated. The safety of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs, sartans) in patients with a history of ACEI-induced angioedema remains a matter of debate. Although large observational studies and meta-analyses suggest that ARBs carry a risk comparable to placebo [70, 71], pharmacovigilance data report a slightly higher incidence with agents such as losartan and irbesartan [72, 73]. Accordingly, ARBs are generally regarded as a safer alternative to ACEIs, though caution remains warranted. Patients should be informed of the potential risk of recurrence, monitored closely during the first year of therapy, and equipped with an individualized action plan should symptoms arise. For other drugs with a known theoretical mechanism of inducing bradykinin-dependent edema (neprilysin inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors – gliptins, tissue plasminogen activators, mTOR and renin), there is very limited clinical evidence of their use in patients with HAE. Therefore, an individual assessment of the risks and benefits in a given clinical situation should be made.

C1INH DEFICIENCY IN PATIENTS WITHOUT A FAMILY HISTORY (EXCLUSION OF AAE-C1INH)

Symptoms of AAE-C1INH often resemble those of HAE-C1INH, but they differ in key aspects:

In diagnostically uncertain cases, genetic testing for SERPING1 mutations may be helpful [74]. Patients with AAE-C1INH often present with – or subsequently develop – C1INH autoantibodies, hematologic disorders (particularly monoclonal gammopathy or lymphoproliferative malignancies), or autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus [55, 75, 76].

DIFFERENTIATION FROM HAE-NC1INH

Key clinical features of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor (HAE-nC1INH) [77–79]:

lower penetrance: not all individuals with predisposing mutations develop symptoms,

later onset: symptoms typically begin later in life than in patients with HAE-C1INH,

female predominance: females are more frequently affected,

hormonal influence: estrogens, including those in contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, may significantly affect disease expression, particularly in certain subtypes,

variable attack frequency: patients may experience infrequent attacks, sometimes with long symptom-free intervals,

absence of classic prodrome: erythema marginatum, often seen in HAE-C1INH, is typically absent in HAE-nC1INH,

skin changes: bruising or subcutaneous bleeding may precede swelling episodes – a finding less commonly observed in other HAE types.

C1INH concentration and functional activity are normal. Aside from genetic mutations identified through targeted gene panels or whole genome sequencing [55], no additional validated biomarkers are currently available to reliably diagnose specific HAE-nC1INH subtypes [80].

AE-UNK AND HAE-UNK

These forms of angioedema have unknown etiology and unclear pathophysiology and are diagnosed by exclusion of other causes [9, 81]. In the literature, these are also referred to as idiopathic histaminergic or non-histaminergic (non-mast cell-mediated) angioedema, depending on response to mast cell–targeted therapies [55]. If there is a positive family history, the condition is classified as HAE-UNK. The DANCE classification also includes eosinophilic angioedema (Gleich syndrome) under the AE-UNK subtype [9].