Introduction

Colorectal cancers are among the most common malignant neoplasms in the world. It is estimated that in 2020, approximately 1.9 million new cases were diagnosed, while 0.9 million deaths were recorded in the same year [1]. In general statistics, colorectal cancer is third in terms of incidence and second in the category of causes of deaths from neoplastic diseases [1]. In Poland, during the year 2017, cancer of the colon and rectum in terms of incidence was fourth among men and fifth among women [2]. Despite the progress in diagnostics and therapy, a systematic increase in these statistics is observed.

Neoplastic transformation occurs as a result of numerous disturbances in the genome of the cell, including chromosomal instabilities which induce DNA damage. One of the main factors leading to DNA damage is metabolic stress, which also leads to protein oxidation and lipids peroxidation. The concept of this phenomenon was presented in 1985 by Helmut Sies [3]. Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the ability of the cell to neutralize and eliminate them. The increase in the level of ROS may be related to both the increase in their production by cell metabolism and their accumulation, or slowing down of the processes of their excretion [3–9]. In the process of carcinogenesis, the increase in ROS leads to DNA damage, which translates into the formation of genetic mutations, but also impairs apoptosis and stimulates proliferation. Therefore, an increase in ROS may be one of the reasons for the formation of cancer cells, contributing to the increase in invasiveness and intensification of metastatic processes [3–12]. The factors responsible for the overproduction of ROS include smoking, alcohol, stress, toxins, and inflammatory processes related to metabolic diseases, as well as diet and lifestyle [4–12]. These factors also take part in the etiopathogenesis of colorectal cancer [4, 13, 14].

While oxidative stress plays a key role in the course of cancer, there are no data on the relationship between redox homeostasis and nutritional status in patients with colorectal cancer. At the same time, there are no data on malnutrition, the course of surgical complications, and the redox balance in patients with cancer of the colon and rectum. The results of recent studies question the need for antioxidant supplementation in the course of cancer.

Aim

The aim of the study was to evaluate and compare the total antioxidant capacity (TAC), total oxidant status (TOS), and malondialdehyde (MDA) as a lipid peroxidation product between healthy controls and patients with colorectal cancer as well as in patients with colorectal cancer in terms of the metabolic and nutritional status. TAC and TOS characterize the resultant ability of the biological system to neutralize ROS and therefore provide much more information than the assessment of individual antioxidants and oxidants separately. Additionally, we calculated the oxidative stress index (OSI) and the TAC/MDA ratio to assess the redox balance.

Material and methods

The study included 50 patients with colorectal cancer treated surgically in the 2nd Clinical Department of General, Gastroenterological and Oncological Surgery at the Medical University of Bialystok Clinical Hospital in the years 2017–2019. There were 19 women and 31 men in the study group. The mean age of the examined patients was 67 years, with the youngest patient being 35 years old and the oldest being 90 years old. In all colorectal carcinoma (CRC) patients, the tumor differentiation grade was G2 (moderately differentiated). All 50 patients had adenocarcinoma (Table I). Nutritional history was collected in all subjects on admission: the loss of body weight during the last 3 months, body mass index (BMI), and assessment using the NRS 2002 scale. The levels of total protein and albumin in the blood serum, as well as complete blood count (CBC) for anemia, were also determined. All blood samples were collected from the patients in the morning on the day of admission to the clinic. Histopathological diagnosis was consistent with WHO standards. On the other hand, tumor stage, lymph node metastases, as well as distant metastases, and disease advancement were assessed based on the TNM UICC classification.

Table I

Characteristic of the study group

In the control group, which was selected by sex and age to match the study group, samples were obtained from 40 healthy subjects attending follow-up visits at the Specialist Dental Clinic (Department of Restorative Dentistry) at the Medical University of Bialystok from January 2018 to January 2019. Only patients with normal complete blood count results and biochemical blood tests (Na+, K+, creatinine, INR, ALT, AST) were included in the control group.

The numbers of patients in the study and the control groups were set based on our previous experiment involving 15 patients (online ClinCalc software). The variables used for the sample size calculations were concentrations of NO and AGE. The level of significance was set at 0.05 and the power of study was 0.9. The ClinCalc sample size calculator provided the sample size for one group. The minimum number of patients was 38.

Body mass index

BMI was determined according to the formula: body weight/height in meters2; the result < 18.49 indicates underweight, 18.5–24.99 normal body weight, 25–29.99 overweight, while over 30 indicates obesity (first, second and third degree).

Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 – NRS-2002

The values obtained by patients according to the NRS-2002 scale were also assessed. A score equal to or greater than 4 points on this scale may suggest malnutrition. The NRS-2002 is presented in Table II.

Table II

Nutritional Risk Screening 2002

Blood collection

Fasting venous blood (10 ml) was collected from all patients on an empty stomach and upon overnight rest. The S-Monovette K3 EDTA blood collection system (Sarstedt, Germany) was used for this. Blood was centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min at +4°C (MPW 351, MPW Med. Instruments, Warsaw, Poland) and the top layer (plasma) was taken. To prevent sample oxidation, 0.5 M butylated hydroxytoluene (20 µl/2 ml plasma or serum) was added [15]. Until redox determinations, all samples were stored at –80°C.

Determination of redox markers

All the assays were performed in duplicate samples. The absorbance/fluorescence was measured using an Infinite M200 PRO Multimode Microplate Reader (Tecan). The results were standardized to 100 mg of total protein. The content of total protein was estimated colorimetrically at a wavelength of 562 nm via the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method [16]. A commercial kit was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific PIERCE BCA Protein Assay; Rockford, IL, USA)

Redox status

To assess the redox status, total antioxidant capacity (TAC), total oxidant status (TOS), and oxidative stress index (OSI) were evaluated. TAC level was determined using the colorimetric method by measuring changes in ABTS•+ (2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate) absorbance at 660 nm [17]. TOS level was analyzed using the colorimetric method by measuring the oxidation of ferrous ion to ferric ion in the presence of oxidants in a sample [18]. OSI is a marker of oxidative stress reflecting the imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants and was calculated using the formula: OSI = [TOS]/[TAC] × 100% [19].

Malondialdehyde (MDA)

The concentration of MDA was determined colorimetrically at 535 nm using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) method [20]. 1,3,3,3 tetraethoxypropane was used as a standard.

TAC/MDA ratio

The plasma TAC/MDA ratio is a marker of antioxidant balance versus oxidative lipid peroxidation reflecting oxidative stress and was calculated by dividing TAC by MDA level.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance level was established at p < 0.05. The normality of the distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test, while homogeneity of variance used the Levene test. In order to compare the differences between two groups with a large number of variables, the multivariate permutational test was performed. Then, to compare differences between two independent groups not showing a normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. The results were presented as median (minimum-maximum). The relationship between the assessed redox biomarkers and clinicopathological parameters was assessed using the Spearman rank correlation. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to assess the diagnostic utility of the redox biomarkers. Area under the curve (AUC) and optimal cut-off values were determined for each parameter, ensuring high sensitivity and specificity. The minimum number of patients was 38. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, USA) and Past 4.13 (Øyvind Hammer).

Results

Clinical findings

Tumor staging

One patient had a T1 lesion, 39 patients had a T2 lesion, and T3 was found in the remaining 10 patients. In the case of lymph node metastases, in 30 patients no such metastases were found (N0), in another 10 metastases from 1 to 3 lymph nodes (N1a, N1b) or deposits from neoplastic cells (N1c) were found. However, in the remaining 10 subjects, the involvement of more than 3 lymph nodes (N2) was found. Distant metastases, i.e. the feature of M1, were found in 8 patients, and no distant metastases were found in the remaining 32 patients (Table I).

Postoperative complications

To assess the possible influence of oxidative stress on postoperative complications, a group of 13 patients with such complications was selected. The type of complications is presented in Table I.

BMI

In the study group, based on the BMI index, no underweight patients were found, 18 patients had normal body weight, and the remaining 32 patients were overweight or obese (Table I).

Weight loss

After analyzing unintentional weight loss, the study group included 11 patients who did not notice any weight loss in the 3 months preceding hospitalization. In the remaining 39 cases, weight loss ranged in extreme cases from 2 kg to 20 kg and amounted to an average of 7.93 kg (Table I).

Levels of total protein and albumin

The levels of total protein and albumin were assessed – normal values of total protein were found in 30 patients, while in 20 patients these values were reduced (the level of total protein over 5.5 g/dl was taken as the normal value). The correct level of albumin was found in 22 patients, while it was low in another 28 patients (the level of albumin above 3.5 g/dl was taken as the correct value) (Table I).

NRS 2002 scale (Table II)

In 12 patients, the sum of points was 3, which indicates a proper nutritional status. However, in the remaining 38 respondents, this result was 4 or more points, which may indicate malnutrition (Table I).

Anemia

Anemia was diagnosed in 30 patients (RBC < 4.2 × 106/µl, HGB < 13 g/dl in male patients and RBC < 3.5 × 106/µl, HGB < 12 g/dl in female patients), while the RBC and HGB values were normal in the remaining 20 patients (Table I).

Comparison of TAC, TOS, OSI, MDA, and TAC/MDA between patients with colorectal cancer and the control group

We found a statistically significantly higher TAC value (p < 0.0001) in the control group compared to patients with colorectal cancer (Figures 1 A, E). However, the values of TOS, OSI, and MDA were statistically significantly higher in the group of patients with colorectal cancer in comparison to the control group (p < 0.0001) (Figures 1 B–D). Also, the TAC/MDA value (p < 0.0001) was statistically significantly higher in the control group compared to patients with colorectal cancer (Figure 1 E).

Figure 1

Total antioxidant/oxidant status in patients with colorectal cancer and the control group. A – TAC control vs. colorectal cancer, B – TOS control vs. colorectal cancer, C – OSI control vs. colorectal cancer, D – MDA control vs. colorectal cancer, E – TAC/MDA control vs. colorectal cancer

TAC – total antioxidant capacity, TOS – total oxidant status, OSI – oxidative stress index, MDA – malondialdehyde.

Comparison of TAC, TOS, OSI, MDA, TAC/MDA depending on the chosen nutrition indicators

We detected a considerably higher TAC level (p = 0.0017) and a considerably lower TOS level in patients with CRC with normal BMI (≤ 24.9 kg/m2) compared to those with high BMI (> 24.9 kg/m2) (Figures 2 A, B). We did not observe any statistically significant differences in values of OSI, MDA, and TAC/MDA (Figure 2 C–E) in those groups. We also observed a higher TAC level in patients without weight loss in comparison to patients with weight loss (p = 0.0407) whereas MDA concentration was higher in patients with weight loss compared to those without weight loss (p = 0.0025); no differences between the TOS, OSI, and TAC/MDA values were observed (Figures 2 F–J). TOS and OSI were significantly higher in patients with anemia than in patients without anemia (p = 0.0228, p = 0.0395), while no statistically significant differences in TAC, MDA, and TAC/MDA were observed (Figures 2 K–O). TAC was significantly higher whereas TOS, OSI and TAC/MDA ratio were significantly lower in patients without symptoms of malnutrition than in patients with malnutrition (p = 0.0344, p = 0.0174, p = 0.0358, p = 0.0200, respectively); there was no differences in MDA value (Figures 2 P–T). Patients without postoperative complications had lower TOS and MDA and a higher TAC/MDA ratio in comparison with the group with complications (p = 0.0437, p = 0.0109, p = 0.0325 respectively); there were no statistically significant differences in values of TAC and OSI (Figures 2 U–Y).

Figure 2

Comparison of TAC, TOS, OSI, MDA, TAC/MDA depending on the chosen nutrition indicators. A – TAC and BMI, B – TOS and BMI, C – OSI and BMI, D – MDA and BMI E – TAC/MDI and BMI, F – TAC and weight loss, G – TOS and weight loss, H – OSI and weight loss, I – MDA and weight loss, J – TAC/MDA and weight loss, K – TAC and anemia, L – TOS and anemia M – OSI and anemia, N – MDA and anemia, O – TAC/MDA and anemia, P – TAC and nutrition status, Q – TOS and nutrition status, R – OSI and nutrition status, S – MDA and nutrition status, T – TAC/MDA and nutrition status U – TAC and complications, V – TOS and complications, W – OSI and complications, X – MDA and complications, Y – TAC/MDA and complications

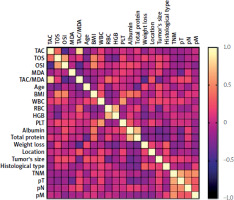

Correlations

We observed a negative correlation between TAC levels and the patient’s age (p = 0.0344, R = –0.3206). We also demonstrated positive correlations between BMI value and TOS (p = 0.0042, R = 0.4921), and OSI (p = 0.005, R = 0.4988). Moreover, statistically significant correlations were found between OSI and tumor size (p = 0.046, R = 0.3256) (Figure 3).

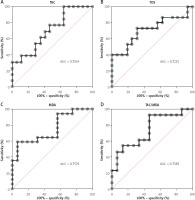

ROC analysis

The ROC analysis demonstrated that the evaluated parameters (TAC, TOS, MDA, TAC/MDA) are potentially useful biomarkers for differentiation of CRC patients with and without postoperative complications (Table III). The optimal cut-off values were calculated, and the ROC curves are presented in Figure 4. Particular attention should be paid to MDA and TAC/MDA, for which AUC values in the presence of postoperative complications were respectively 0.7574 (MDA) with a cut-off value > 171.2 µmol/l, 64.71% sensitivity and 68.75% specificity, and 0.7385 (TAC/MDA) with a cut-off value > 171.2 µmol/l, 64.71% sensitivity and 68.75% specificity. We also observed a very high diagnostic value of TAC (AUC = 0.7014) and TOS (AUC = 0.7125). The cut-off value for TAC was < 1.393 mmol/l with sensitivity of 61.54% and specificity of 64.71% and for TOS was > 9.956 µmol H2O2 Equiv/l with sensitivity of 73.33% and specificity of 68.75%.

Figure 4

A – ROC analysis of TAC in CRC patients and without postoperative complications. B – ROC analysis of TOS in CRC patients and without postoperative complications. C – ROC analysis of MDA in CRC patients and without postoperative complications. D – ROC analysis of TAC/MDA in CRC patients and without postoperative complications

AUC – area under curve, ROC – receiver operating characteristic, TAC – total antioxidant capacity, TOS – total oxidant status, OSI – oxidative stress index, MDA – malondialdehyde.

Table III

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis in CRC patients with and without postoperative complications

Discussion

An increasing number of studies emphasize the role of oxidative stress in the process of carcinogenesis. Oxidative stress is defined as a disturbance of the balance between oxidation and anti-oxidation processes, i.e. overproduction of free oxygen radicals, while impairing the cell’s neutralization and elimination [3–7, 10, 11, 19, 21, 22]. Excessive presence of free radicals can lead to damage to lipids and proteins, as well as bicarbonates or nucleic acids. This may lead to damage to the nucleotide sequence, and consequently to DNA strand breakage, oxidation of purine and pyrimidine bases, and changes in DNA methylation [3, 5, 23–25]. All these phenomena can result in chromosomal instability, which is one of the hallmarks of malignant transformation in the large intestine. The most common DNA damage caused by oxygen free radicals is the modification of GC base pairs with subsequent deletions, translocations or insertions of these bases [23, 26]. Another type of mutations associated with DNA damage by oxygen free radicals is microsatellite instabilities – they contribute to the disruption of DNA repair mechanisms during replication, and thus intensify the multiplication of already existing errors.

Oxidative stress deactivates DNA repair systems, resulting in the formation of pathological cell lines, while oxygen free radicals stimulate the proliferation of cancer cells through the selective activation of transcription factors. There are more and more papers describing the impact of oxidative stress on the development of cancers such as breast, lung, esophageal, thyroid, or cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, e.g. colon, pancreatic, or stomach cancer [4, 6–12, 14, 21, 23–28].

Malnutrition or cachexia is observed frequently in oncological patients, which may increase the risk of postoperative complications. This problem is also raised in the context of oxidative stress. Both the cachexia of patients, which is characteristic of e.g. cancer of the esophagus, pancreas or bile ducts and stomach, and overweight and obesity, which are considered to be among the factors predisposing to the occurrence of e.g. cancer of the endometrium or cancer of the large intestine and rectum, affect antioxidant barrier disorders, and even intensify oxidative stress [4, 5, 10, 29–37].

It is estimated that the risk of postoperative complications in patients operated on due to gastrointestinal cancers ranges from 14 to 34%, with the risk of death related to the procedure being about 25% [29, 38]. Factors that may affect postoperative complications, apart from the nutritional status, include the patient’s age, the presence of additional diseases, the patient’s efficiency, the stage of progression of the underlying disease, the extent of the surgical procedure, the surgical technique itself or the operator’s experience, and the body’s response to the procedure operational – which is treated as an injury. The most common complications after coloproctological procedures include postoperative wound infection, urinary tract infection associated with bladder catheterization, pleural effusions or congestive pneumonia, intra- and post-operative bleeding, anastomotic leaks and fistulas, and intra-abdominal abscesses [23, 29, 39]. Postoperative complications can be divided according to the degree of severity into five grades: Grade I is defined as any deviation from the normal postoperative course that does not require pharmacological treatment, endoscopic intervention, surgery or interventional radiology. Grade I also includes postoperative wound infection, which does not require treatment in the operating room. Grade II involves treatment complications in which blood substitutes, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, and parenteral nutrition are required. Grade III is the need for repeated surgical, endoscopic or interventional radiology intervention. Grade IV requires treatment in the ICU to treat complications. Grade V is the death of the patient [29, 39].

In our research, we found that patients with colorectal cancer develop oxidative stress, with significantly increased oxidation over antioxidant processes. This is evidenced by statistically significant differences in the levels of TAC, TOS, and OSI, as well as MDA and TAC/MDA in the group of cancer patients compared to the control group. In the control group, in which antioxidant processes prevailed, TAC and TAC/MDA values were statistically significantly higher than in the group of patients with cancer. TAC is an indicator describing the total antioxidant status, while TAC/MDA may indicate the effectiveness of the antioxidant barrier, because we compare here the total antioxidant status with malondialdehyde – a product of lipid peroxidation, resulting from oxidative damage. In turn, the values of TOS, i.e. total oxidative status, OSI (oxidative stress index), being the ratio of TOS/TAC and MDA, were statistically significantly higher in the group of patients with intestinal cancer compared to the control group, so in these patients, oxidation processes prevailed. This is due to the fact that in patients with colorectal cancer, the antioxidant barrier is disturbed, which may be evidenced by a decrease in TAC and a significant increase in the total oxidative status, and thus an increase in OSI – this parameter illustrates the relationship between oxidants and antioxidants, while its increase proves the advantage of oxidation processes over the processes of removing free radicals [14, 28]. The fact of increased oxidative stress in patients with colorectal cancer underscores even more the increase in MDA, which is the end product of lipid peroxidation. Its increase clearly reflects the pathological influence of free radicals on lipids (their damage). This aldehyde is highly cytotoxic and carcinogenic. MDA-DNA oxidation products have mutagenic properties and induce, among other things, mutations in tumor suppressor genes. The weakening of the antioxidant barrier is also reflected in the decrease in TAC/MDA.

In our study, we also assessed the impact of preoperative levels of TAC, TOS, OSI, MDA or the TAC/MDA ratio on the occurrence of possible postoperative complications. In the available literature, studies describe the impact of preoperative oxidative stress and its impact on postoperative complications, but no analysis was performed on redox parameters assessing the total antioxidant capacity or oxidative status. We were the first to perform a cumulative analysis of TAC, TOS, OSI, MDA and TAC/MDA. We found statistically significant differences in the level of TOS, MDA and TAC/MDA in the group of patients with complications compared to the group of patients without complications. Among patients with postoperative complications, both preoperative TOS and MDA levels were statistically significantly higher (p < 0.05), while TAC/MDA was statistically significantly lower compared to patients without complications. In order to better understand this phenomenon, it is necessary to treat surgery as an injury, which is to some extent a controlled injury, but an injury nonetheless. During each procedure, the integrity of the human body is violated, such as tissue damage or ischemia, which may cause intensification of pro-inflammatory processes or lead to overproduction of reactive oxygen species. The inflammatory response intensifies: TLRs and NLRs are activated, PAMP and DAMP are recognized, and the synthesis of cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β is increased [23, 25]. At the same time, throughout this situation, ROS begin to play an important role as mediators of injury [23, 25]. As mentioned above, reactive oxygen species are overproduced, which overwhelms the body’s antioxidant capacity to fight and neutralize these molecules. As a consequence, it leads to damage to proteins, lipids, bicarbonates or nucleic acids. All these phenomena lead to the formation of postoperative complications, which are often associated with organ failure, perfusion disorders, sepsis, or even fever [23, 25]. Based on the above observations, we can conclude that patients with high preoperative levels of TOS and MDA and a reduced TAC/MDA ratio are patients with the most disturbed antioxidant barrier, and the compensatory properties of the antioxidant barrier are practically exhausted; hence these patients are most at risk of postoperative complications.

Both our results and those of Leimkuhler et al. [25] confirm the relationship between the intensity of preoperative oxidative stress and the occurrence of possible postoperative complications. An additional fact in favor of the above statement is the analysis of ROC curves for TAC, TOS, MDA, TAC/MDA that we conducted. Our study clearly demonstrated that these values for TAC (AUC = 0.7014), TOS (AUC = 0.7125), MDA (AUC = 0.7574), and TAC/MDA (AUC = 0.7385) can be considered predictive factors, allowing us to select the group of patients with the highest risk of complications.

Among the relationships observed by us, the relationship between the severity of oxidative stress and the nutritional status of patients with CRC assessed on the basis of the NRS 2002 scale seems to be most important. In the group of malnourished patients with CRC, the values of TOS and OSI were statistically significantly higher (p < 0.05), compared to the group with a normal nutritional status. In turn, the values of TAC and the TAC/MDA ratio were significantly higher in CRC patients with normal nutritional status. The above observation seems to be an important premise to consider preoperative nutritional intervention, aimed at improving the nutritional status of patients, which could reduce oxidative stress, and most importantly, perhaps reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications.

We observed significant differences in the level of TOS and OSI depending on BMI (p < 0.05). It is not surprising that the levels of TOS and OSI were significantly higher in patients with elevated BMI. At the same time, there were no statistically significant differences in the levels of TAC, MDA, and the TAC/MDA ratio in patients with BMI > 24.9 kg/m2 compared to patients with a normal BMI. These results can be explained by the fact that oxidative stress plays an important role as a critical factor linking obesity with its complications [34, 40]. Oxidative stress in obese patients is associated with, inter alia, excessive production of peroxides from NADPH oxidase, autooxidation of glyceraldehyde, or results from activation of protein kinase C, and hexamine or polyol pathways. Other factors that contribute to the intensification of oxidative stress include hyperleptinemia, chronic inflammation, and postprandial production of free oxygen radicals. All this leads to an increase in the production of reactive oxygen species and disturbances in the antioxidant barrier. At the same time, in our study, we found a decrease in the TAC level in patients with a decrease in body weight compared to patients without such a decrease. In the group of patients with weight loss, there were no patients with BMI values that could indicate malnutrition. In addition, among the patients with recorded unintentional weight loss, there were no people with a reduced or even normal BMI, because all these patients, despite losing weight (up to 20 kg in extreme cases), were still overweight. Indirect confirmation of the correctness of this observation was found in the work of Choromańska et al. [40], in which the relationship between weight loss and the level of oxidative stress in obese patients was assessed. The study was conducted on a group of obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. TAC levels were monitored 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. The authors detected similar relationships to ours, i.e. an increase in the TAC level, which was observed with a decrease in body weight. At the same time, we found a statistically significant difference in the level of MDA in the blood serum, to the disadvantage of patients with weight loss (the level was significantly higher in them (p = 0.0025); however, it did not translate into the value of the TAC/MDA ratio, which was associated with significantly higher TAC values (p = 0.04) in this group.

Another clinically significant observation seems to be the relationship between the severity of oxidative stress and preoperative anemia. We observed a statistically significant increase in TOS and OSI values in patients with anemia compared to patients with normal morphology values. Anemia in patients with colorectal cancer may have various causes. Bleeding is common in patients with intestinal cancer, which is occult and more frequent in patients with cancers located in the cecum, ascending colon, and partly in the transverse colon. In patients with neoplastic lesions in the left part of the colon, i.e. in the descending colon, sigmoid colon or rectum, we are dealing with overt bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract. Another potential cause of anemia is disturbances in iron metabolism [30, 32–34]. Here, too, there may be several reasons, i.e. iron deficiency in the body, or disorders in its absorption. Another factor that may affect anemia in patients with colorectal cancer is the secretion of substances by the tumor that imitate or block normal endocrine signals responsible for the development of the hematological lineage.

Some limitations of our study should be mentioned. Although the sample size was quantified statistically, the study group was relatively small. Therefore, further studies on a larger group of colorectal cancer patients are needed. The concentration of redox parameters was assessed only in blood samples (serum/plasma), giving our results an approximate value. Their level should also be assessed in postoperative tumor tissues, and evaluation of blood-tissue correlations would then be advisable. Because we measured only selected redox biomarkers, we cannot fully explain the redox impairment in patients with colorectal cancer. However, our work also has evident strengths. These include the careful selection of a study and control group without comorbidities.

Summing up, based on our own observations, we can conclude that the preoperative assessment of TAC, TOS, OSI, MDA, TAC/MDA may carry clinically significant information about the possibility of postoperative complications. These observations may also be important in the context of the implementation of supplementation/nutrition, which may increase the level of antioxidant protection and thus affect the condition of the patient and minimize the development of postoperative complications.

Conclusions

Preoperative determination of selected oxidative stress parameters such as TAC, TOS, OSI, MDA, or TAC/MDA ratio may facilitate selection of patients who may experience postoperative complications. High levels of TAC, and thus the predominance of antioxidation over oxidation, found before surgery, have a significant impact on the postoperative course. With the intensification of oxidative stress (↑ TOS, ↑ OSI, ↑ MDA, ↓ TAC, ↓ TAC/MDA), the risk of postoperative complications increases. The increase in oxidative stress seems to be related to nutritional disorders that we observe in patients with colorectal cancer. The prevalence of oxidation processes is inextricably linked to the occurrence of malnutrition. Therefore, the implementation/use of appropriate supplementation/nutritional treatment can significantly affect the patient’s condition and minimize the development of postoperative complications