Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) typically manifests in regions of the body characterized by squamous epithelial tissue. Given the absence of squamous epithelial cells within the liver, primary hepatic squamous cell carcinoma is infrequent in this anatomical site. The challenge of early diagnosis is compounded by the absence of distinct clinical and imaging features specific to this condition [1]. SCC arising in the liver is primarily documented in association with conditions such as hepatic cysts, hepatolithiasis, or hepatic teratomas [2, 3]. While the precise pathogenesis remains elusive, there have been suggestions indicating that the origin of primary SCC (PSCC) could arise from the transformation of biliary epithelium with chronic inflammation or metaplastic changes followed by neoplastic transformation of pre-existing hepatic cysts [4]. Squamous cell carcinoma of the liver represents an exceedingly rare pathological entity, documented in a mere 32 cases within the English literature from the 1970s to the present day. This scarcity underscores the limited prevalence and knowledge surrounding this particular malignancy [5]. Some investigators have demonstrated a correlation between SCC of the liver and the male gender [6]. The prognosis associated with this tumor is notably dismal, with only a minority of patients demonstrating survival exceeding 12 months even following treatment, as documented in reported cases [7].

We present a case report of SCC of the liver, together with a brief review of SCC of the liver that is available in the literature. The review documented and analyzed key data from each case report, including information on the first author, publication year, patient demographics (age and gender), comorbidities, tumor characteristics, treatments administered, and survival outcomes.

A 50-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency room due to intermittent fever episodes, mild discomfort in the right upper abdominal quadrant, and general weakness. The patient had no past medical history, was a farmer by profession, did not consume alcohol, and had stopped smoking for the past 2 years. Also, there was no past history of squamous cell malignancy and no family history for cancer. His vital signs upon admission were normal. His blood tests showed a raised white blood cell count of 14.2 K/µl (lab normal range 4–11 K/µl), C-reactive protein of 8.96 mg/dl (normal range of < 80 mg/dl), with liver function tests all being within the normal range. Blood, urine, and stool cultures were negative for bacterial infection, and chest X-ray showed no signs of respiratory infection. Considering the patient’s occupation as a farmer, there was a possibility of skin injury-related bacterial or zoonotic diseases, such as brucellosis. However, the tests for skin injury bacteria and cultures were negative. Cancer blood markers (a-FP, CEA, and CA 19-9) were also negative. A computed tomography (CT) scan was then performed, revealing a hypovascular mass with a maximum diameter of about 10 cm located mainly in the quadrate lobe of the liver and extending anteriorly to the capsule (Figure 1). Since the mass resembled a complex infected mass with indirect signs of abscess formation, and the patient continued to be septic after conservative management, CT-guided drainage with a pigtail tube was attempted. Some minor output of purulent fluid was analyzed and concomitant biopsies were taken at the time. The patient did not improve and was referred to the surgical department. The case was presented at a multidisciplinary meeting to further evaluate the patient’s condition and the CT scans, and a more aggressive approach was adopted. Inevitably, a diagnostic laparoscopy was performed, revealing a large inflammatory mass of solid consistency, located mostly in the central liver segments. A cystic cavity was difficult to identify and there was no sign of an abscess related to the mass. Surrounding purulent fluid was identified. Macroscopically the mass had spread to the falciform ligament, greater omentum, and the diaphragm; thus, it was declared unresectable. A no-touch technique was performed, and only biopsies were obtained. The rest of the abdominal cavity was verified to be free of masses. The histopathological report was positive for squamous cell carcinoma, which was verified as primary via PET-CT (Figure 2). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy did not show any other masses that could be considered primary. PD-L1 was found positive, as well as p63 and p40, which are markers of squamous differentiation, with no loss of nuclear expression of MMR proteins (low microsatellite instability probability). The patient after control of septic complications was referred to the oncological department for further treatment. The initial treatment included 5 cycles of chemotherapy using carboplatin and paclitaxel. A follow-up CT scan 47 days after the start of chemotherapy revealed that the mass had enlarged in size by 50%, while the secondary lesions had grown in size and number by 150%, and there were newly found scattered peritoneal metastases (Figure 3). He was then treated with immunotherapy using pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor. The patient did not complete the offered treatment, since he became unwell, with further progression of the disease during this period. He was admitted to the oncology department, were he received best supportive care, and he died 4 months after the diagnosis.

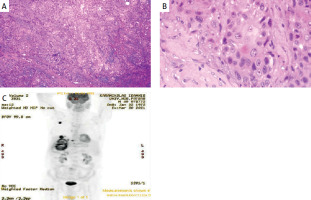

Figure 1

Baseline contrast-enhanced CT: hypodense lesions measuring 10.5 × 9.8 cm in segment IVa, IVb, V, VIII resulting in mass effect of the main portal branches, which are patent

Figure 2

A – Microphotograph depicting a squamous cell carcinoma composed of nests, masses and small groups of cells opposed to one another in a mosaic tile arrangement. Large islands of intratumoral necrosis are also present. B – There is histologic evidence of squamous differentiation in the form of extracellular keratin. The cells have eosinophilic cytoplasm and intercellular bridges. The presence of dyskeratotic cells is also obvious. Keratocysts or keratin pearls are not evident. C – PET-CT scan showing the liver mass

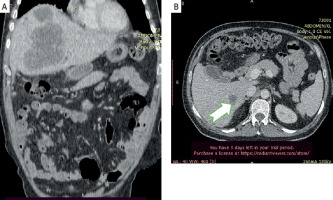

Figure 3

Follow-up CT scan 47 days after the first chemotherapy session (5 in total) showing growth of the mass and of the satellite lesions (arrow)

The clinical presentation of hepatic PSCC lacks specificity, with patients often being diagnosed at an advanced stage due to the absence of specific indicators in laboratory tests and imaging studies. Abdominal pain is the most frequently reported symptom, while only a minority of patients experience weight loss, with jaundice being a late presentation of the disease [6].

Specific laboratory findings indicative of hepatic dysfunction correlated with a history of hepatitis are not typically observed. However, abnormalities in liver function tests may be detected. Serum a-fetoprotein (AFP) levels are usually within normal limits, while elevated levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen 125 (CA125), and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) are relatively common. However, their specificity for diagnosis cannot be estimated [7].

Approximately 30% of patients demonstrate leukocytosis, often in the absence of fever, which may be attributed to tumor-related leukocytosis (TRL) [8, 9]. The occurrence of TRL, a paraneoplastic syndrome, has been documented in 10%–20% of individuals with cancer and is linked to an unfavorable prognosis. Notably, TRL has been found to exhibit limited responsiveness to traditional treatment modalities such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, resulting in suboptimal survival rates [10, 11].

The imaging characteristics of hepatic PSCC deviate from a typical enhancement pattern. Dynamic (CT) scans reveal heterogeneous masses with low density. Some of these masses may coincide with hepatic cysts or intrahepatic biliary duct stones. Following contrast administration, most cases display either a rim or delayed enhancement, similar to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) imaging patterns. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CEMRI) and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) yield atypical findings with peripheral and irregular enhancement [9, 10]. In contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS), heterogeneous enhancement observed during the arterial phase is succeeded by washout in the late phase, a characteristic indicative of malignancy [11].

The etiology of PSCC remains poorly understood. Known risk factors of primary liver tumors such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C infection, or cirrhosis do not appear to be consistently linked with the pathogenesis [10, 11]. However, a potential association between the presence of hepatic cysts or hepatolithiasis and the development of primary hepatic SCC cannot be excluded [9, 10]. Chronic inflammation as the primary mechanism, resulting from infection of hepatic cysts and irritation of bile ducts by stones, may induce squamous metaplasia, leading to the transformation into SCC in some cases [9].

The main trigger event hypothesis is difficult to verify, and further research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms of squamous transformation [12]. On the other hand, documented risk factors for PSCC such as ciliated hepatic foregut cyst (CHFC) need further elucidation. This entity consists of a rare cystic lesion that arises from the embryonic foregut. With approximately 100 cases reported, it is commonly identified in segment IV of the liver, is typically asymptomatic, and is incidentally found on abdominal imaging. It is important to consider this entity in the differential diagnosis of atypical liver lesions, since CHFC carries a risk of transformation into squamous cell carcinoma [10, 13]. Definitive diagnosis is dependent upon pathological analysis and immunohistochemistry and requires a thorough systemic evaluation to rule out the presence of metastatic lesions or any primary liver malignancy. Local or peritoneal tumor spread after biopsy could be a major concern. Therefore, determining the state of resectability is a crucial a step before undertaking any invasive diagnostic procedure. In our case, PSCC resembled a liver abscess, and an invasive approach was performed only after meticulous staging. Owing to the infrequency of PSCC, a standardized treatment approach has yet to be established. Surgical intervention, interventional therapies, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy might be considered [14]. Nevertheless, the rarity of this entity precludes a standardized treatment protocol, and there is no universally established treatment regimen for SCC of the liver. Data from the literature are limited to case reports, including patients who received aggressive surgical treatment or chemotherapy with limited overall survival. However, radical surgical intervention, with intention to treat, seems the only approach that may offer a survival benefit encompassing liver resection with free margins in the context of liver surgery principles [11]. Prognosis is poor, within a range of 5 months, with palliative measures to an extended duration of 17 months [9, 10]. Minimal or nonsurgical invasive treatment such as cyst drainage of a complex cystic mass or partial cystectomy needs to be carefully considered. A high degree of suspicion seems to be the first step towards a proper diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Locoregional treatment modalities including thermal ablation, cryoablation, radiotherapy, and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) have limited evidence regarding efficacy in terms of oncological control of the disease [11, 12]. In our case, the patient experienced pain in the upper right quadrant and intermittent fever. Imaging results indicated a liver abscess. Despite negative bacterial cultures, the presence of fever could indicate necrosis within the tumor. If a liver abscess is suspected but does not respond to appropriate treatment, including antibiotics and pus drainage, the possibility of malignancy should be considered [13]. On the surface, a skeptical attitude towards PSCC of the liver could be totally justified since, as already mentioned, it is an exceptionally rare malignancy with limited documented cases in the medical literature. The reported cases occur across diverse age groups and genders, with imaging evaluation including multiple low-density lesions and single lobulated masses, occasionally with single lesions of partially cystic appearance, predominantly located in the right lobe or segment 4 of the liver [14]. The prognosis of PSCC of the liver remains dismal, with many patients succumbing to the disease within a relatively short time from diagnosis. Despite the experience of therapeutic modalities used in other liver tumors, recurrence of the disease remains a significant concern. Further research and a comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving this malignancy are imperative for the development of effective therapeutic strategies and improvement of patient outcomes. In synopsis, the occurrence rate of primary liver SCC remains exceedingly rare. Further investigation is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of carcinogenesis and etiopathogenesis. The prognostic determinants remain ambiguous. Radical surgical intervention stands as the primary recommendation. Alternative therapeutic modalities such as chemotherapy, arterial embolization, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and immunotherapy present alternatives for the management of primary hepatic SCC.