INTRODUCTION

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a rare lethal demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) caused by John Cunningham virus (JCV) [1]. JCV is a widespread virus with more than 80% of adults having IgG antibodies against it [2]. PML develops due to a reactivation of a latent JCV infection in individuals with cellular immunodeficiency [2, 3]. There is no proven curative therapy against PML. In the era before human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pandemic, the most common underlying condition that PML was associated with were haematological malignancies [2]. Since the beginning of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), the HIV infection remains a leading cause of PML in the general population [4-7]. However, this may vary between countries – in Finland, the most common illnesses associated with PML are still haematological malignancies as in pre-HIV era [8]. According to the European Centre for Diseases Control and Prevention (ECDC) PML is a rare AIDS-defining disease which in 2021 was responsible for 2.6% of opportunistic infections in the European Union (EU) [9]. Prior to antiretroviral therapy, HIV was the primary illness in 80% of the PML cases and 8% of people with AIDS were diagnosed with PML [10]. The introduction of antiretroviral medications led to a significant decrease in both morbidity and mortality due to the opportunistic infections in people with HIV, except that PML is still an incurable disease [11, 12].

We present the case report of a young male who developed PML as the first manifestation of newly diagnosed HIV infection.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 33-year-old male was presented to the neurological care with right homonymous hemianopsia, abnormal gait and slurred speech on April 12th, 2023. With a history of progressive vision impairment since mid-February, his primary complaint was of blurred vision. According to the patient, before the symptoms first occurred he had been healthy, had not taken any medication and had no history of using any psychoactive substances. His family history of neurological diseases or premature deaths was also negative.

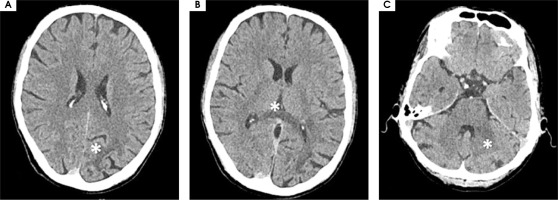

On February 27th, 2023 he was hospitalized in the neurological ward due to a sudden progression of sight loss to right homonymous hemianopsia. In the computed tomography (CT) scan hypodense lesions were found in the left parietal lobe, left middle cerebellar peduncle and the trunk of the corpus callosum. The lesion in the left parietal lobe was described as surrounded by vasogenic oedema (Figure I). The brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with 1.5 Tesla scanner was performed and a nonenhancing lesion in the white matter of the left cerebellar hemisphere was reported along with the signs of restricted diffusion. The images suggested an acute ischemia. Similar lesions were also found in subcortical and periventricular white matter of left parietal lobe (Figure II).

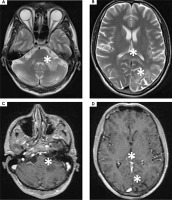

As the diagnosis was not finalized, an MRI-spectroscopy was performed with 3 Tesla scanner (March 2023). The non-enhancing lesions in the white matter of both parieto-occipital areas crossing the corpus callosum (a “barbell sign”) as well as in both hemispheres of the cerebellum were found [13]. The comparison of the MRI images with the spectra of the lesions (significantly increased choline and decreased N-acetylaspartate) suggested a pathology of white matter due to inflammation or demyelinisation rather than mitochondrial encephalopathy or toxic damage (Figure III).

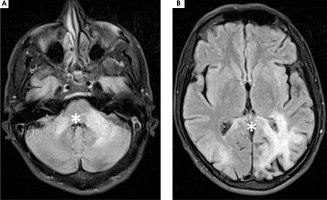

Figure I

Computed tomography axial scans showing hypodense lesions in (A) left parietal lobe, (B) trunk of corpus callosum (white star), (C) left middle cerebellar peduncle (white star)

The patient visited several neurologists and neurosurgeons, but no diagnosis was reached. Finally, he was advised the brain biopsy in order to find the underlying causes of his condition, which he denied. On admission to the neurological ward on April 12th the patient was alert, keenly responsive and well-oriented. An estimated assessment of the visual field suggested right homonymous hemianopsia. The neurological assessment revealed a cerebellar “staccato” speech, slight dysmetria (L > R), positive Romberg test and cerebellar ataxic gait. The patient was malnourished with his body mass of only 42.5 kg.

The results of a CT scan were comparable with those performed in February.

The laboratory tests, including those for common infectious diseases, enhanced MRI and perimetry were performed.

The results of laboratory tests are presented in Table 1.

The MRI showed a slight increase in the volume of the lesions in comparison to that performed in March (Figure IV). The patient then underwent a consultation with a neurosurgeon and no indications for surgery were found.

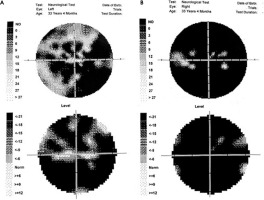

The perimetry results are presented in Figure V.

Due to the positive result of HIV screening test, the patient was referred to the Regional Hospital for Infectious Diseases in Warsaw on April 13th, 2023. The diagnosis of HIV infection was confirmed with molecular tests. On admission the patient’s immunological profile showed lymphocytes CD4 count of 18 cells/µl and CD8 of 343 cells/µl, CD4/CD8 ratio was 0.05; HIV-1 viral load was 36 000 copies/ml.

After excluding any contraindications, a lumbar puncture was performed. Results of an analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can be seen in Table 2. A broad panel of tests against various pathogens in CSF was ordered (BioFire FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis Panel). Other common CNS opportunistic infections such as cerebral toxoplasmosis, tuberculous meningitis, cryptococcal meningitis, and cytomegalovirus infection were excluded. JCV DNA in CSF was detected with polymerase chain reaction (PCR), other tests were negative as shown in Table 3.

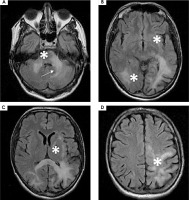

Figure II

1,5 T magnetic resonance axial scans showing T2 hyper intense lesions in (A) left middle cerebellar peduncle and cerebellar hemisphere (white star), (B) left parietal lobe and trunk of corpus callosum that are (C, D) T1 post contrast hypointense and non-enhancing (white stars)

Finally, the diagnosis of the AIDS-associated PML was reached.

Additional blood tests were performed in order to exclude any other potential opportunistic infections. The serological markers of Treponema pallidum, Toxo-plasma gondii, Cryptococcus neoformans, cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), tuberculosis, Mycobacterium other than tuberculosis (MOTT) infections were all negative.

The combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) was started on April 14th, 2023 with dolutegravir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine. The tests to define drug resistance to cART showed the presence of V106I mutation, with no resistance to the tested non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) antiretroviral drugs. The patient established undetectable viremia 2 months after the initiation of treatment; however, lymphocyte T CD4 count remained < 50 copies/µl. The patient’s immunological status was determined three times as shown in Table 4.

Rapid decrease of HIV-1 viremia raised concerns for evolution of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Corticosteroids were prescribed and a gradual decrease of dosage was recommended.

Additionally, intravenous pentamidine was administered monthly as a primary prophylaxis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP).

After obtaining results of HIV-1 tropism, which showed 74.9% false positive rate (FPR), oral maraviroc 300 mg twice a day was added to cART. The following weeks showed a deterioration of the patient’s neurological state and an increase in the volume of the lesions, as numerous new lesions were detected in the MRI performed in May 2023. The lesion in the left cerebellar hemisphere increased in volume abutting-but-sparing the left dentate nucleus – “shrimp sign” (Figure VI) [14]. This led to discontinuation of maraviroc therapy in June 2023.

Figure III

3T magnetic resonance spectroscopy showing spectra of (A) healthy tissue and (B) lesion. 3T magnetic resonance FLAIR axial scans showing lesions in (C) both cerebellar hemispheres and (D) both parieto-occipital areas crossing the corpus callosum (barbell sign) (white stars)

Table 1

Laboratory test results at the admission to the hospital

The follow-up hospitalisations took place monthly (May, June, July 2023). On May 9th, 2023 a futile therapy protocol was signed due to worsening of the patient’s clinical state with progression of neurological deficits. The patient was awake but without any verbal contact, bedridden and requiring a permanent supervision of a care provider. The patient’s body mass declined to 34.5 kg. Due to ineffective oral feeding, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was performed on June 14th, 2023. The patient was discharged on June 21st and transferred to a palliative care facility, where he died on August 11th, 2023.

DISCUSSION

We have decided to present this case in order to raise awareness of HIV infection and PML.

The patient presented identified as a ‘men who have sex with men’ (MSM), although he withheld this information till long after the onset of his symptoms. He was unaware of his HIV-status. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2021, two-thirds of all new HIV diagnoses were among MSM. In EU/European Economic EAA MSM population accounts for approximately 40% of new HIV diagnoses (UNAIDS). Among the most common barriers to HIV testing are low self-perceived risk of HIV and fear of stigmatization [15].

Table 2

Cerebrospinal fluid test results

| Result | Reference range | |

|---|---|---|

| Color | Clear, colorless | |

| Proteins | 0.45 g/l | 0.12-0.60 |

| Glucose | 3.03 mmol/l | 2.20-4.40 |

| Chloride | 119 mmol/l | 115-129 |

| Lactic acid | 1.2 mmol/l | 1.13-3.23 |

| Blood cell count | 2 | < 5 |

| Mononuclears cel count | 2 |

Table 3

Results of the infectious disease panels from the cerebrospinal fluid

Table 4

Patient’s immunological status during the combined antiretroviral therapy

| April 2023 | May 2023 | June 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytes CD4+ count | 18 | 16 | 4 |

| Lymphocytes CD8+ count | 343 | 420 | 954 |

| CD4+/CD8+ | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| HIV-1 viral load (copies/ml) | 36 000 | < 20 | Undetectable |

The first symptom reported by the patient was the loss of sight, although he also presented with a history of the preceding significant weight loss, which is a common sign of acute HIV infection. Other neurological symptoms followed. Studies suggest that clinical manifestations of PML may depend on the underlying condition. In the case of AIDS-associated PML the most common symptoms include motor weakness (42%), speech or language disorder (40%), cognitive and behavioral issues (36%) as well as gait abnormality and incoordination (35%) [16]. The loss of sight reported by the patient is more common in natalizumab-associated PML (19% vs. 41%) [16].

Figure VI

A-D) 1.5 T magnetic resonance FLAIR axial scans showing an increase in the volume of the lesions as well as numerous new lesions (white stars). A) Shrimp sign (white arrow)

Late HIV diagnosis is a significant problem across Europe with the highest numbers found in Eastern Europe. It is defined as the first HIV diagnosis when a patient has a lymphocyte T CD4 count < 350 cells/µl or has an AIDS-definitive event, regardless of the lymphocyte T CD4 count [17]. Both of these were met in the case of the patient presented. In Poland, it is estimated that 64% of persons diagnosed with HIV infection are so called late presenters which is the highest percentage among the European countries [18].

The most common risk factor of PML in people with HIV is the lymphocyte T CD4 count < 200 IU/ml [19], which was the case of the patient presented in this paper. In the Swiss HIV Cohort Studies (159 patients diagnosed with AIDS-associated PML), the median lymphocyte T CD4 count at the time of PML diagnosis was 60 cells/ml (23-140) and in the patient presented the count was 18 cells/µl [20].

With the progressive neurological symptoms, compatible neuroimaging findings (hyperintense lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and T2 weighted images) and a positive PCR for JCV in CSF the patient met the criteria of the definite PML diagnosis according to the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) [16].

As no causative treatment for PML is known, the standard therapy in AIDS-related PML consists of cART. The administration of the antiretroviral therapy tends to increase lymphocyte T CD4 count and lower HIV viral load [21]. Yet, in the presented case a significant decrease of HIV viral load was not followed by the increase of lymphocyte T CD4 count.

Despite rapid decrease of HIV viral load, the deterioration of the patient’s neurological condition was observed. Maraviroc was added to cART, following the standards of care in HIV-associated opportunistic infections. There are casuistic cases of complete resolution of lesions in MRI after maraviroc regimen [22]. Unfortunately, in the presented case the following weeks showed further worsening of the patient’s condition, which led to discontinuation of maraviroc therapy as futile treatment protocol was started.

A rapid decrease of HIV viremia along with the gradual worsening of the patient’s neurological state was interpreted as the evolution of IRIS. A significant worsening of neurological symptoms after starting cART is typical for PML-IRIS as evidence of rapid immune recovery. It is estimated that 4%-22% of people with HIV-related PML develop IRIS [10]. The chances of PML-IRIS occurrence increase in patients who start cART while having a low lymphocyte T CD4 count (especially < 50 cells/µl) and who experience a fast HIV RNA decrease [22].

Before the introduction of antiretroviral therapy, the median survival rate after the diagnosis of PML was 6 months. Nowadays it is more than 2 years [23, 24]. Lymphocyte T CD4 count < 50 cells/µl, visual loss and dysarthria, as well as evolution of PML-IRIS were seen in this patient’s case, which are all common risk factors of poor prognosis in HIV-related PML, usually leading to death or discharge to hospice [25]. Despite all our efforts, the patient died more than 5 months after the onset of his neurological symptoms and 4 months after the PML dia gnosis.

Raising the awareness among clinicians of different CNS presentations, in which early HIV screening is pivotal, is crucial [26]. The Polish AIDS Clinical Society re commends to screen for HIV all patients who suffer from neurological disorders such as PML, polyneuropathy, neurotoxoplasmosis, encephalopathy of unknown origin or progressive dementia [27]. Each of the AIDS-associated CNS opportunistic infections, i.e. cerebral toxoplasmosis, tuberculous meningitis, cryptococcal meningitis or cytomegalovirus infection has a typical clinical and radiological pattern.

CONCLUSIONS

The HIV screening test should be performed early in the diagnostic process, particularly in MSM patients, and in patients with unexplained neurological symptoms, and without prior history of neurological issues, as it may enhance patients’ chances for correct diagnosis and initiation of proper treatment.

Medical staff, as well as the general population, should receive continuous education regarding risk factors, modes of transmission, and the importance of early HIV diagnosis. Public awareness campaigns should aim to inform the general population about all aspects of HIV transmission and prevention. Slogans such as Undetectable equals Untransmittable [28] serve as effective, accessible tools for conveying essential information.

Within the so-called late HIV diagnosis, the occurrence of CNS opportunistic infections should be considered right after the HIV diagnosis.