INTRODUCTION

Psychedelics represent a unique category of psychoactive substances, known for their ability to transform states of consciousness and perception [1]. Although the term “psychedelics” is often used in the context of a wide range of perception-altering substances, there is a particular distinction for “classic psychedelics” [2]. This group includes compounds such as lysergic acid diethyl amide (LSD), psilocybin, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and mescaline [3]. What distinguishes these substances and unites them as a group is their shared mechanism of action. They act as agonists on the brain’s 5-HT2A serotonin receptors, which is directly responsible for their primary effect of altering perception [4]. Because of this, these substances were once incorrectly labeled as hallucinogens. However, unlike hallucinations, they modify perception without distorting reality [5].

While psychedelics have been used for centuries in traditional and medicinal practices [6], the stigma surrounding them emerged in the 1960s, when they became linked to the countercultural movement. This, along with the failure to establish safe, controlled clinical trials, led to their criminalization through the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. As a result, misconceptions were fueled, and negative stereotypes were reinforced, causing long-lasting stigmatization and public fear that persists to this day [7]. And yet, the urgent need for breakthroughs in the psychiatric field has revived interest in psychedelic substances [8]. Currently, they are increasingly recognized as promising alternatives, which – contrary to antidepressants – can address the root causes of mental health conditions rather than merely alleviating their symptoms [9-11]. Throughout the years, research on psychedelics has proven them effective in conditions where the existing treatments fall short, namely treatment-resistant depression [12] and anxiety among terminally ill patients [13]. Moreover, according to preliminary clinical evidence, the synergistic combination of psychedelic substances and psychological support may bring benefits in the treatment of many mental disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder [14, 15], post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [16, 17], addictions [15, 18], eating disorders [16, 19], and many others [20]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that psychedelics, as opposed to antidepressants, can have long-lasting benefits with little administration, even after just one dose [18, 21]. All these promising results have marked a paradigm shift towards what is being termed “the psychedelic renaissance” [22]. This has led to an increase in popularity of psychedelic substances in the therapeutic context, sparking both curiosity and hope. Yet, it is important to remain cautious and avoid overly optimistic thinking, as well as extremes that suggest psychedelics are completely free of long-term risks [23]. For instance, a recent study suggests that psychedelics can affect the heart, potentially increasing the force of contraction and heart rate, which may lead to arrhythmias [24]. Moreover, psychedelics can lead to challenging psychological experiences, such as “bad trips”, which are often characterized by intense fear, confusion, or paranoia, potentially resulting in temporary mental distress or lasting psychological discomfort [25, 26].

In most countries, psychedelics cannot be prescribed or used outside officially approved scientific studies. Interestingly, there are few exceptions (Commonwealth of Australia, State of Oregon in United States of America) [27, 28]. However, many individuals interested in this mind-altering experience are not waiting for legal approval and are currently experimenting with personal use.

For example, research estimated that 5.5+ million people in the U.S. used hallucinogens in 2019, which represents an increase from 1.7 percent of the population aged 12 years and over in 2002 to 2.2 percent in 2019 [29]. Furthermore, the Global Psychedelic Survey (GPS) in 2023 analyzed 6,379 responses from 85 countries, with most respondents coming from Canada/US (n = 4,434), Europe/ UK (n = 771), and Australia/New Zealand (n = 864). The participants were primarily adults aged 21 and older, and the survey revealed that psilocybin, LSD, and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) were the most commonly used substances, and the motivations for their use centered around personal growth [30]. Similarly, a Norwegian study involving 841 participants, of whom 72% were male, and 88% were aged 45 or younger, reported using classic psychedelics primarily for recreational (46.1%) or therapeutic (42.3%) purposes [31].

When it comes to the Polish society, the PolDrugs 2021 survey, which collected responses from 2,373 Polish individuals, revealed that psychoactive substances were widely used across various age groups. A significant proportion of users were young adults, with 59.3% identifying as male and most falling within the 18-24 age range. Users most commonly reported consumption in social settings, typically with friends (59.4%) or at home (45.7%), primarily for recreational purposes [32].

Similarly, a study published in 2024 by Adamczyk et al. [33] investigated the motivations and contexts of psychedelic use among 862 Polish users of LSD and psilocybin. The study found that motivations such as self-exploration (70%), spiritual purposes (31%), and self-healing (27%) were linked to more intense ego-dissolution experiences, while curiosity (81%) was associated with less profound effects. Although psychedelics were most frequently used in natural outdoor settings (33%) or at home (25%), the study concluded that the physical environment and social context had limited influence on the intensity of experiences, with personal motivations playing a significantly more influential role.

The primary objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of psychedelic use in the Polish adult population, along with the patterns and practices associated with their consumption – such as the substances used, frequency, and context of intake. An additional aim was to explore the motivations behind psychedelic use, evaluate the nature of these experiences (including the occurrence of “bad trips”), and assess the attitudes of Polish men and women towards psychedelics and psychedelicassisted therapy (PAT). Concerning the last goal, we tested the hypothesis that lifetime meditation (mindfulness) practice would be associated with more positive attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT. This hypothesis was based on the observation that individuals who practice mindfulness often embrace holistic and integrative health approaches, which may lead to increased openness to exploring psychedelics and psychedelic interventions [34]. Mindfulness, defined as open and non-judgmental awareness of the present moment, is commonly linked with traits such as openness to new experiences, curiosity, and a flexible, accepting mindset [35]. We also sought to determine if previous experiences with psychedelics are related to a better general attitude toward psychedelics and PAT.

METHODS

Participants

The study was conducted in December 2022 on a national random-quota sample of adults aged 18 and older, N = 1051; 563 women and 488 men with an average age of approximately 45. The sample was a representative group of the adult population living in Poland, considering gender, age, and size of place of residence. The survey was administered online by a platform of a professional research company operating a Polish nationwide panel, and holding a current and valid Interviewer Quality Control Program (PKJPA) certificate, attesting to the high quality of the research services provided. Participation in the study was anonymous and voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who received remuneration in the form of tokens provided by the survey company. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Warsaw (approval number 10/01/2023).

Measures

The survey consisted of three parts. The first part gathered participants’ demographic information. The second part examined their use of psychedelic substances and their subjective views on psychedelics and PAT. The third assessed their perception and attitude towards psyche delics using the Concerns and Openness toward Psychedelic Scale (COPS) [36]. In the initial section of the survey, participants provided demographic details, such as age, gender, place of residence, marital status, and level of education. They also reported on their meditation habits, including lifetime prevalence of meditation (mindfulness) and frequency of practice. The second part began with participants rating their attitudes towards psychedelics and PAT on a 5-point Likert scale, followed by questions on their previous use of psychedelics, frequency of use, type of substances taken, the settings in which they were taken, and motives behind their use. The last two questions were assessed using multiple-choice options. For example, the motivation question was framed as: “What prompted you to take psychedelics? Check all relevant reasons below,” followed by a list of possible motivations (see Figure III). Similarly, the question about the context of psychedelic use – “In what kind of setting have you taken psychedelics?” – was followed by a list of possible locations (see Figure IV). Participants who had a prior experience of psychedelics were then asked to evaluate their experiences, and their influence on their life and to disclose if they had ever experienced a “bad trip.” Next, they were asked about their views on PAT and psychedelics on a 5-point Likert scale. To ensure clarity, the second part of the survey started with a specific definition of psychedelics, acknowledging their broad interpretation. Similarly, terms like “bad trips” and “psychedelics therapy” were clearly defined before delving into the related questions. The third part of the survey utilized the newly developed COPS to delve deeper into attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT [36]. The data on COPS are not the subject of the present study.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using several measures in IBM SPSS for Windows (release 28.0). Missing data was excluded from the analyses. Prevalence of lifetime psychedelic consumption, sociodemographic characteristics, assessment of psychedelic experiences, and evaluation of attitudes towards psychedelics and PAT were analyzed descriptively and reported as frequencies. Pearson’s χ2 for independence tests was used to evaluate the relationships between the prevalence of psychedelic use and sociodemographic characteristics among those who had prior experience with psychedelic use. The predictors of attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT were determined using hierarchical logistic regression analysis.

To assess whether previous personal experience with psychedelics was associated with more favorable attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to compare attitude scores between individuals with past psychedelic use and those without such experience. The p-value for all analyses was set to p < 0.05, and confidence intervals were set to 95%.

RESULTS

It was found that 6% of respondents in the sample had taken psychedelics at least once in their lives. According to Poland’s Central Statistical Office (GUS) data, in 2022 the population of individuals aged 20 and over in Poland comprised 30,122,873 people, thus the maximum estimation error for a sample size of 1051 individuals was 2%. It can therefore be assumed that between 4% and 8% of individuals (from 1,204,915 to 2,409,830 individuals) took psychedelics at least once in their life. The prevalence of the use of psychedelics was significantly higher in men than in women (8.8% vs. 3.6%), ϕ = 0.11, p < 0.001. According to GUS data, in 2022 the population of men aged 20 and over in Poland was 14,327,227 individuals, thus the maximum estimation error for a group size of 488 men was 3%. It can therefore be assumed that between 5.8% and 11.8% of men (from 830,979 to 1,690,613 men) took psychedelics at least once in their lives. According to GUS data, in 2022 the population of women aged 20 and over in Poland was 15,795,646 individuals, thus the maximum estimation error for a group size of 563 women was 2%. It can therefore be assumed that between 1.6% and 5.6% of women (from 252,730 to 884,556 women) took psychedelics at least once in their life.

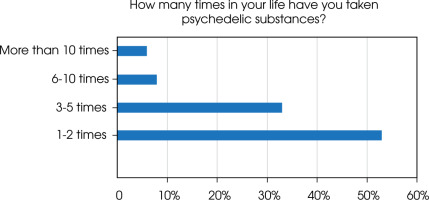

Figure I shows the percentage values of the number of psychedelic substances taken by individuals who had such prior experience. Most individuals among those who had such an experience (53%), took these substances 1-2 times, and the smallest percentage (6%) more than 10 times.

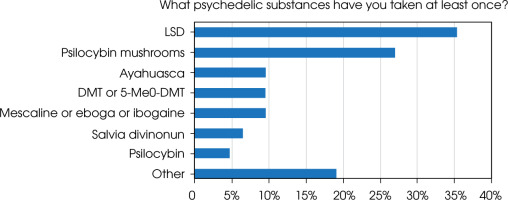

Figure II shows the percentage values of the specific psychedelic substances used in the sample. The most used psychedelic substance was LSD, which was taken by 35% of the respondents who had a prior psychedelic experience. Psilocybin mushrooms (“magic mushrooms”) came second, as taken by 27% of the individuals (Figure II).

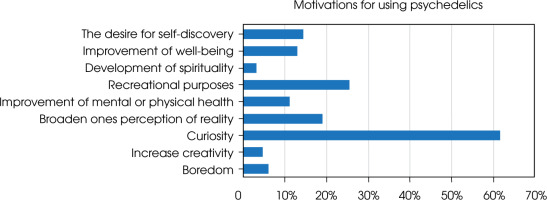

Figure III depicts the percentage values of specific motivations the participants had for taking psychedelics. Curiosity was the most common prompt to reach for psychedelics (62%), and recreational purposes, such as enhancing the experience at a party were the second but far less common (25%).

Figure IV shows the percentage values of the specific context of psychedelic use. Home was the most frequent setting for participants taking psychedelics, with 48% choosing this setting, followed by a setting associated with nature (29%).

Table 1 presents the prevalence of psychedelic use at least once in a lifetime according to sociodemographic variables such as age, size of the place of residence, level of education, and marital status. The compilation is supplemented with the values of the Yule’s ϕ coefficient of effect size, along with statistical significance and the results of post-hoc comparisons based on the Bonferroni correction.

The analysis revealed that the lifetime prevalence of psychedelic use was statistically significantly higher in the 25-34 age group compared to individuals aged 55 and older. Additionally, the prevalence was significantly higher among individuals living in the largest cities (with populations over 500,000) compared to those living in cities with populations between 100,000 and 500,000. The most common motivation for using psychedelics turned out to be curiosity (61.9%), particularly among individuals aged 35-44 where it was reported by 90.0% of users. Interestingly, none of the individuals aged 55 or over (0%) was driven by a recreational purposes, such as enhancing experiences at a party. In contrast, 12.5% of individuals aged 18-24 indicated recreational use as a motive, however even in this group curiosity remained a dominant reason (62.5%). It should be noted that the differences in motivations between the age groups were not statistically significant. The desire to improve their mental health was indicated as a motivation significantly more often by women (n = 5; 25.0% of women with psychedelic experience) than by men (n = 2; 4.7%), ϕ = –0.30, p < 0.05. The most common setting in which the participants took psychedelics was home (48%), although also in this area differences between genders were reported: women more often had psychedelic experiences at home (70% vs. 37%), while for men it was “in nature” (37% vs. 10%). Interestingly, none of the respondents in the Polish reported using psychedelic substances during ceremonial practices or in therapeutic setting. Most respondents described their psychedelic experiences as “somewhat unpleasant and somewhat pleasant (mixed),” though women rated them as pleasant significantly more often than men. Among individuals aged 45-55, the most common assessment was “very unpleasant.” The survey also included a question that directly addressed the occurrence of difficult experiences (“bad trips”) associated with taking psychedelics (defined as a terrifying or difficult experience after taking the substance). A majority of respondents (90%) reported never having experienced a “bad trip”. Only 3% confirmed having had such as experience, 5% found the question difficult to answer, and 2% did not remember. These challenging experiences were reported more often by young people (aged ≤ 34).

Table 1

Prevalence of psychedelic use at least once in a lifetime

Table 2

Predictors of attitudes toward psychedelics

| Predictors | Beta | t | p | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.17 | -5.32 | 0.001 | 0.034 |

| Lifetime meditation practice | -0.09 | -2.72 | 0.007 | 0.008 |

Table 3

Predictors of attitudes toward psychedelic-assisted therapy

| Predictors | Beta | t | p | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.11 | -3.29 | 0.001 | 0.014 |

| Lifetime meditation practice | -0.08 | -2.43 | 0.015 | 0.006 |

The study also examined how psychedelic experiences affected the lives of individuals who took such substances. It turned out that 57% of respondents indicated that their experience was neutral (“had no impact”), 10% found it difficult to assess (“hard to say”), while as many as 11% rated the impact as negative. In contrast, 8% described the impact as “positive,” and 6% as “definitely positive.”

The study further examined attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT among Polish women and men.

Attitudes were assessed using a single-item measure on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“definitely negative”) to 5 (“definitely positive”). In the studied group of 1051 participants, the most frequently selected response regarding attitudes towards PAT was “indifferent” (49%). However, gender differences were observed: women more frequently reported a “rather negative” attitude (22% vs. 16%), χ2(4) = 10.31, p = 0.036.

Individuals with prior psychedelic experiences (even those who described them as “bad trips”) displayed more positive attitude than those who had never used psychedelics. Another question using the same scale asked about general attitude towards psychedelics. Across the entire group, a “definitely negative” attitude was the most common (43%), followed by indifferent (29%), and “rather negative” (21%). Women significantly more often reported a “rather negative” attitude than men (24% vs. 18%, p < 0.05), while men more frequently indicated a “definitely positive” attitude (4% vs. 1%, p < 0.05). A negative attitude towards psychedelics was also more common among individuals aged 55 or older compared to those aged 34 and younger.

Next, we focused on the lifetime meditation practice as a possible predictor of attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT, using hierarchical logistic regression analysis. In the first block, participants’ sex, age, and place of residence were included as control variables. In the second block, age and lifetime meditation practice were entered. Predictors were included using a stepwise forward selection method. The results are presented in Table 2 (attitudes toward psychedelics) and Table 3 (attitudes toward PAT).

Lower age and lifetime meditation practice predicted more positive attitudes toward both psychedelics and PAT. Both predictors explained 4.2% of attitudes toward psychedelics, and 2% of PAT variances, respectively.

Finally, we examined whether previous personal experience with psychedelics was associated with more favorable attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests revealed significant differences in attitude scores between individuals with past psychedelic use (n = 53) and those without such experience (n = 860). Specifically, those with past use reported more positive attitudes toward psychedelics (M = 3.09; SD = 1.08) compared to those without such experience (M = 2.81; SD = 0.96), U = 14,012.50, p < 0.001. Similarly, attitudes toward PAT were more favorable among individuals with past psychedelic use (M = 2.87; SD = 1.36) compared to those without such experience (M = 1.95; SD = 1.01), U = 18,816.00, p < 0.022.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the use of psychedelics within the Polish population, shedding light on the prevalence, patterns of consumption, and motivations behind using psychedelic substances. By exploring the socio-demographic factors associated with psychedelic use, as well as the public’s attitudes toward these substances and PAT, we have revealed significant trends that may inform both public health initiatives and future research. However, given the limited number of participants with psychedelic experiences, the results regarding patterns, motivations, and practices associated with their consumption should be interpreted with caution.

The results of the study showed that between 4% and 8% of Polish population, approximately 2 million adults, have taken a psychedelic substance at least once in their lifetime. Most respondents used psychedelics only 1-2 times, which indicates a rare and exploratory nature of their use. LSD turned out to be the most frequently taken substance, closely followed by psilocybin mushrooms, which follows the patterns demonstrated by similar studies in other countries [30]. Men were more likely to use psychedelics than women, which aligned with other findings of research involving a sample of Polish participants [32]. One of the main reasons behind this difference may correspond to conventional thinking of gender differences in risk-taking [37]. The influence of age and place of residence on the prevalence of psychedelic use is also clear, with the largest number of users falling into the 25-34 age range most open to new experiences. In comparison, the results from the aforementioned study on the Polish sample show a younger demographic, with the majority of users being in the 18-24 age group, followed by the 25-30 age group. This difference suggests that while younger adults are generally more open to psychedelic use, there may be some variations depending on the specific population or the sample studied [32].

Residents of large cities were more likely to reach for psychedelics, possibly reflecting greater availability and social connections that support such behaviors. In the present study, curiosity was found to be the primary motivation for experimenting with psychedelics, especially among middle-aged individuals. Interestingly, other research involving Polish participants, indicated that curiosity was linked to less intense psychedelic experiences, while motivations centered on spirituality and personal growth were associated with more profound experiences [33].

In the present study 11% of participants rated the impact of psychedelic experience as very bad. Interestingly, only 3% reported having a “bad trip”, whereas 5% found it difficult to answer, and 2% did not remember. Other studies showed that the possibility of “bad trips” increases with dose, lack of physical comfort, and social support – all of which are controlled in clinical conditions [38]. Future studies may benefit from evaluating the rate and intensity of unpleasant experiences and the perception of psychedelic experiences’ impact on individuals in the context of psychiatric comorbidity, particularly anxiety and stress-related disorders. A recent study reported a very high rate of probable PTSD – 18.8% in Poland [39]. It would be interesting to assess if a relationship obtains between PTSD symptoms and the occurrence of “bad trips”, and the way individuals evaluate the impact of their psychedelic experiences.

In the research reported in this article individuals who experienced unpleasant psychedelic experiences (“bad trips”) displayed a more positive attitude towards psychedelics than those who never had such experiences. Similarly, Gashi et al. [40], found that although the majority of participants experienced “bad trips”, many emphasized positive outcomes, such as significant personal insights and growth. This finding is in line with other studies. For example, 39% of the respondents rated their “worst bad trip” as one of the five most challenging experiences of their lifetime – yet the degree of difficulty was positively associated with enduring increases in well-being [38, 41]. This may suggest that even difficult psychedelic experiences can be perceived as valuable, in line with observations that stressful experiences may lead to significant, positive transformations in the individual’s life [42]. It may also suggest that there is a need to move away from negative perceptions and highlight their potentially positive outcomes [23].

Among the respondents who had taken psychedelics, consumption in a home setting was dominant, especially among women. This may indicate a need for safety and control when exploring psychedelics, and that, contrary to popular belief, their use at rave parties is not the most common form of recreational use. Psychedelics are criminalized in Poland, so access to them in controlled therapeutic settings is still limited. Consequently, the present study did not record the use of psychedelics in a therapeutic or even ceremonial context, contrary to global trends, where the use in these contexts is gaining in popularity [43]. Most of the surveyed individuals who had a psychedelic experience described it as “somewhat unpleasant and somewhat pleasant (mixed),” although women were found to report it more often as pleasant than men. At the same time, 57% of all respondents stated that psychedelic experience had no impact on their lives, 11% rated the impact as very bad, 8% as good, and 6% as very good. These results differ from those obtained in clinical studies where psychedelics were given in doses and contexts appropriate for therapeutic purposes. For example, Roland Griffiths’ team from Johns Hopkins Hospital revealed that as many as 67% of volunteers who took a dose of psilocybin in a study with a double-blind trial that used methylphenidate as the comparator substance rated their psychedelic experience as the single most significant experience of their life or as one of the five most significant experiences of their life [41].

Regarding attitudes toward psychedelics in the sample, this representative group of Polish adults most often had negative attitudes, with women and individuals aged 55 or older having more negative attitudes compared to younger individuals. The attitude toward PAT was overall somewhat more favorable, as the most frequently indicated response was “indifferent.” However, similar to attitudes toward psychedelics, women were more likely to report a “rather negative” attitude. These gender differences in attitudes toward psychedelics are consisted with prior research indicating that women often hold more cautious or negative perspectives compared to men [44].

Additionally, a positive correlation between personal psychedelic experience and favorable attitudes toward these substances was observed, aligning with findings from another research [45]. To further explore this hypothesis, we conducted a between-group analysis, which confirmed that both attitudes toward psychedelics and attitudes toward PAT were significantly more favorable among individuals with past psychedelic use, compared to those without such experiences. These findings are consistent with a recent systematic review [46]. Personal experience with psychedelic substances may play a role in reducing anxiety and negative stereotypes associated with their use [45]. We also found that, along with the lower age, lifetime meditation practice was the predictor of more positive attitudes towards both psychedelics and PAT. As far as we know, this is the first study that directly assesses the relationship between lifetime meditation practice and attitudes toward psychedelics. Interestingly, these findings are broadly in line with research that found several synergistic effects and mechanisms of action between meditation and mindfulness-based interventions and psychedelic treatments [47]. Results of the attitude evaluation show a negative societal perspective on these substances. Based on this finding, it may be concluded that raising social awareness is needed, mostly in terms of scientific knowledge and potential therapeutic use of psychedelic substances.

However, before advocating for changes in social attitudes, it is essential to thoroughly evaluate the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, focusing not only on their effectiveness but also on their safety. Although more research is needed to make the claim fully convincing, current scientific findings suggest that using classic psychedelics is generally safe, and their side effects are minor and transient. Scientific research consistently evaluates psychedelics as significantly less harmful to users and society compared to alcohol and most other controlled substances. In landmark comparative studies on drug-related harms using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) LSD was ranked among the least harmful substances, both to individuals and society, with “magic mushrooms” receiving the lowest overall harm score [48]. These results have been replicated in studies conducted in the Netherlands, Europe, and Australia [49-51]. Additionally, surveys involving substance users and experts consistently placed LSD and psilocybin in the lowest-harm categories, a finding further supported by another survey of drug users [52, 53]. A recent review of the adverse effects of psychedelics indicated that medical risks associated with these compounds are minimal, and many of the ongoing negative perceptions about psychological risks are not substantiated by current scientific evidence [23]. Importantly, most reported adverse effects are not observed when psychedelics are used in regulated or medical settings [23]. While some side effects, such as the risks of psychotic episodes or overdose are rare and generally reported in isolated cases, they must be still mitigated through careful patient selection and thorough preparation. Over the past decade, research and clinical experience have increasingly demonstrated that psychedelics can be safely administered under medical supervision, with progressively well-defined safety guidelines. Despite the growing body of evidence supporting their effectiveness in treating a wide range of medical conditions and confirming their safety in regulated and medical contexts, psychedelics remain a contentious topic, overshadowed by past stigmatization and ongoing concerns about potential risks and dangers.

LIMITATIONS

This study has several strengths, including using a representative sample of Polish internet users. To our knowledge, this is the first study that describes the prevalence and factors associated with the recreational use of psychedelics in a representative sample of Polish participants. It is also one of the first which has evaluated the factors associated with attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT, particularly meditation practice. The research, however, has its limitations such as a small number of participants with psychedelic experience (only 63 reporting such experiences out of 1051) and also relying on self-reported measures. Despite these limitations, the results are informative for future research directions on psychedelics and their social perception in Poland. Moreover, understanding the motivations for taking psychedelics, the context of their use, and the societal attitudes toward psychedelic use in the therapeutic context may help develop educational programs and influence legislative changes that could foster scientific research into psychedelic therapy in Poland. Future studies should aim to include a broader sample with psychedelic experiences to provide a more reliable assessment of the context and structure of their use.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that the prevalence of psychedelic use in Poland was around 6% (ranging from 4% to 8%). The majority (52%) of those who had used psychedelics had one or two experiences, with LSD and psilocybin mushrooms being the most commonly used. Curiosity was the most common motivation for using psychedelic substances, and home was the preferred setting. Most users described their psychedelic experiences as “somewhat unpleasant and somewhat pleasant (mixed)”, with 3% reporting a “bad trip”. The majority of respondents (49%) indicated an indifferent attitude towards PAT, while a negative attitude was predominantly regarding general disposition towards psychedelics (43%), particularly in women. Finally, young age and lifetime prevalence of meditation (mindfulness) practice were found to be predictors of more positive attitudes toward psychedelics and PAT.