Introduction

Worldwide, more than 1 million people are diagnosed with colon and rectal cancer annually. Colorectal cancer is worldwide the second most common malignancy in women and the third most common malignancy in men [1]. It is also the third leading cause of cancer death in both sexes [2]. In addition, regarding the frequency of tumors based on their location, about 42% of them occur in the right and proximal colon, and the other 55% involve the sigmoid and rectum [3].

Colorectal cancer is a multifactorial disease, as genetic factors, lifestyle factors such as obesity, non-balanced diet, and excessive alcohol consumption, and the presence of non-inflammatory conditions of the intestine play a role in its occurrence [4–10].

Patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer may present with iron deficiency anemia, weight loss, fatigue, atypical abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, and changes in bowel habits [11]. About 75% of colon and rectal cancers are sporadic, and only 15–20% occur in people with a positive family or personal history of malignancy or benignity [12].

Colorectal cancer is usually asymptomatic in its early stages. Thus, screening is a valuable tool for detecting treatable lesions. However, the presence of symptoms or the finding of a pathological result in any of the related tests, such as the detection of blood in the stool, may raise the suspicion of colorectal cancer. In such a case, a colonoscopy and biopsy of any suspicious lesion is necessary for its diagnosis, which is also an advantage over any other examination [13–20].

Screening is an important means of both reducing loss of life and the costs of health systems burdened by long-term hospitalizations and expensive treatment regimens, which in the end may not be sufficient to treat the patient. However, the success of cancer prevention systems is inextricably linked to the economic prosperity of the health system and the existence of organizations. Also, patient participation plays a role in the successful operation of such a system [21, 22].

Considering the above, this study aims to assess healthcare workers’ information about screening tests of colon cancer and additionally to investigate whether they are medically examined for this type of cancer in Greek hospitals.

Methods

A multicenter series study was carried out. The structure and information of the general section were based on the search in online databases (PubMed, Scopus, etc.), online information of the WHO and corresponding European organizations, and the guidelines regarding the diagnosis and treatment of colon cancer.

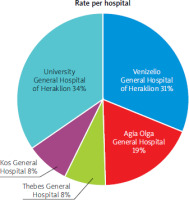

The starting point for this study was the creation of a questionnaire (Supplementary), whose completion was anonymous, and which consists of four parts: demographic information, questions about knowledge regarding screening, questions about the implementation of screening for women, and questions about the implementation of screening for men. The hospitals selected were three tertiary and two secondary units: the University General Hospital of Heraklion, Venizelio General Hospital of Heraklion, Agia Olga General Hospital, Kos General Hospital, and Thebes General Hospital. The specific questionnaire was distributed to the employees (medical, nursing, administrative, and other paramedical staff) of all the clinics and departments of the five hospitals over approximately 6 months, following the approval of the study by the scientific council of each institution. Usually, the collection of the questionnaires was conducted on the same day and rarely the day after the distribution, in consultation with the employees of the respective clinic/department and with the condition that each employee can fill in only one. A total of 1470 questionnaires were collected: 506 from the University General Hospital of Heraklion, 456 from Venizelio General Hospital of Heraklion, 273 from Agia Olga General Hospital, 123 from Kos General Hospital, and 112 from Thebes General Hospital.

Statistical analysis

The R language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org) was used to analyze the data. For descriptive statistics, we applied the mean value ± standard deviation (mean, SD) to continuous variables with a normal distribution and the median value and interquartile range (median, IQR) to non-normal variables, while for categorical variables we calculated the frequency and relative frequency for each element of the relevance tables. Normality of distribution was evaluated with the Shapiro-Wilk test.

We used bar graphs for frequencies and boxplots for continuous variables to visualize the data.

For hypothesis testing, regarding continuous variables, Student’s t-test (or Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric data) was used in the comparison between subgroups, while for the comparison of the sample with the correct answer, the one-sample t-test was used.

Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test (Fisher’s exact test for expected frequencies < 5) and ordinal variables using the Kruskal rank-sum test. The level of statistical significance was set at 5% (α = 0.05).

Results

A total of 1470 questionnaires were answered, of which 506 (34.4%) were from the University General Hospital of Heraklion, 456 (31%) from Venizelio General Hospital of Heraklion, 273 (18.6%) from Agia Olga General Hospital, 123 (8.4%) from Kos General Hospital, and 112 (7.6%) from Thebes General Hospital, i.e. 235 responses came from secondary and 1235 from tertiary hospitals. The percentages of participants from different hospitals are illustrated in Figure 1.

Of the 1470 responses, 985 (67.01%) were female and 485 (32.9%) were male. The average age of the participants was 43 and 52 years, respectively. Regarding the marital status of the participants, 893 (60.9%) were married, 447 (30.5%) were single, 114 (7.8%) were divorced, and 13 (0.9%) were widowed. Regarding their job position in each nursing institution, the respondents were 556 (37.8%) physicians, 493 (33.6%) belonged to the nursing staff, 232 (15.8%) belonged to the other paramedical staff, and the remaining 188 (12.8%) were administrative employees. Regarding the educational level of the participants, 228 (15.5%) had completed secondary education, 896 (61%) tertiary education, and 345 (23.5%) had a master’s or doctoral degree. Also, 675 (45.9) of the participants had a salary below 1000 euros and 794 (54.1%) above 1000 euros. Finally, regarding the period of their work at the respective nursing institution, 384 (26.1%) had worked at the hospital for 0–5 years, 236 (16.1%) for 5–10 years, and 849 (57.8%) for more than 10 years (Figure 2).

Regarding the respondents’ knowledge of colon cancer prevention, we had the following results. 94.3% (1377) answered that the examination of choice was colonoscopy. 47.3% (641), the majority, believe that the appropriate age is 50 years. In the case of a positive family history, 34.6% (506) answered 45 years, while 59.3% (867) answered 35 years (Tables I–III).

Table I

Absolute number and response rates of respondents to the screening test for colon cancer

| Screening test | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Fecal occult blood test | 69 (4.7) |

| Computed tomography (CT) | 5 (0.3) |

| General blood test | (0.7) |

| Colonoscopy | 1377 (94.3) |

Table II

Absolute numbers and percentages of respondents regarding the age at which colorectal cancer screening should be performed for the first time

| Age at which screening test should be performed for the first time | N (%) |

|---|---|

| 35 | 12.6 (184) |

| 45 | 37 (540) |

| 50 | 47.3 (691) |

| 60 | 3.1 (46) |

Table III

Absolute numbers and percentages of respondents’ responses regarding the age at which colorectal cancer screening should be performed for the first time in case of a positive family history

| Age at which screening test should take place for the first time in case of positive family history | N (%) |

|---|---|

| 35 | 867 (59.3) |

| 45 | 506 (34.6) |

| 50 | 84 (5.7) |

| 60 | 5 (0.3) |

The respondents were divided into two age groups: under and over 40 years. The percentage of respondents who answered that colonoscopy is the test of choice for colorectal cancer screening was significantly higher in the age group > 40 years than in the age group > 40 years (> 40 years: 95.3% (839), > 40 years: 92.5% (521), p = 0.035), while no significant differences were found in the percentages of respondents who answered that the starting age for screening is 50 years (> 40 years: 49.3% (434), > 40 years: 44.4% (250), p = 0.077), and that the age of initiation of screening in the case of a positive family history is 45 years (> 40 years: 33.5% (295), > 40 years: 36.6% (206) p = 0.249).

The respondents were divided into 4 work groups: administrative, physicians, other paramedical staff, and nurses. No significant difference was found between the percentages of responses given by the different specialty groups regarding colonoscopy being the test of choice for colon cancer screening (physicians: 93.1% (515), administrative: 94.1% (177), other paramedical staff: 94.8% (218), nurses: 95.3% (466), p = 0.495), while significant differences were found in the percentages of respondents who answered that the age of starting screening is 50 years and the starting age of screening in the case of a positive family history is 45 years: physicians: 62.2% (344), administrative: 43.1% (81), other paramedical staff: 39% (90), nurses: 36.1% (176), p < 0.001, initiation of screening in the case of a positive family history: physician: 46.5% (257), administrative: 27.1% (51), other paramedical staff: 26.4%(61), nurses: 28% (137), p < 0.001).

Next, it was investigated whether further categorization of physicians into laboratory, pathological, and surgical specialties showed significant differences in response rates. No significant differences were found in the percentages of correct answers given by the different specialty groups that colonoscopy is the test of choice for colon cancer screening and that the starting age for screening in the case of a positive family history is 45 years (method of selection: laboratory specialty: 90.8% (69), pathological specialty: 93.7% (298), surgical specialty: 93.6% (147), p = 0.644, initiation of screening in the case of a positive family history: laboratory specialty: 48.7% (38), pathological specialty: 50% (159), surgical specialty: 38.9% (61), p = 0.067), while the percentage of physicians who practice a pathological specialty who answered that the start of symptomatic control is 50 years was significantly higher than the percentages of the other two groups (laboratory specialty: 47% (61.8), pathological specialty: 66.7% (212), surgical specialty: 54.1% (85), p = 0.03) (Tables IV–VI).

Table IV

Absolute number and response rates of respondents who answered colonoscopy as the examination of choice and categorization by age, workgroup, and specialty

Table V

Absolute numbers and percentages of respondents answering 50 years as the age at which a colonoscopy should be performed for the first time and categorization by age, workgroup, and specialty

Table VI

Absolute numbers and percentages of respondents who answered 45 years as the age at which a colonoscopy should be performed for the first time in case of positive family history and categorization by age, workgroup, and specialty

The results were further analyzed and disaggregated across the 5 hospital institutions, as well as secondary and tertiary. Regarding the knowledge about the prevention of colon cancer, significant differences were found in the percentages of correct answers given by the respondents between the 5 hospitals stating that: the examination of choice for the prevention of colon cancer is colonoscopy (Venizelio General Hospital of Heraklion: 96.9% (440), University General Hospital of Heraklion: 93.9% (474), Agia Olga General Hospital: 91.1% (247), Thebes General Hospital: 98.2% (107), Kos General Hospital: 89.3% (109), p < 0.001); and the age at which the above examination should be performed for the first time is 50 years (Venizelio General Hospital of Heraklion: 47.6% (216), University General Hospital of Heraklion: 51.5% (260), Agia Olga General Hospital: 49.8% (135), Thebes General Hospital: 39.8% (43), Kos General Hospital: 47.2% (58), p = 0.001); while no significant difference was found for correctly answering that the age that one should take the above examination for the first time in the case of a positive family history is 45 years (Venizelio General Hospital of Heraklion: 33.5% (152), University General Hospital of Heraklion: 38.0% (192), Agia Olga General Hospital: 35.8% (97), Thebes General Hospital: 33.9% (37), Kos General Hospital: 22.8% (28), p = 0.092). The respondents were then divided into two categories depending on whether they worked in a secondary or tertiary hospital. No significant difference was found in the percentages of correct answers of the respondents regarding examination (secondary: 93.5% (216), tertiary: (94.4% (1161), p = 0.056). A significant difference was found in the percentages of correct answers stating that the age at which the above examination should be performed for the first time is 50 years (secondary: 34.6% (80), tertiary: 49.7% (611), p < 0.001), while no significant difference was found for stating that the age at which screening should be performed for the first time in the case of a positive family history is 45 years (secondary: 28.0% (65) tertiary: 35.9% (441), p = 0.058) (Table VII).

Table VII

Absolute numbers and response rates of respondents in the five hospitals who answered colonoscopy as the test of choice for colon cancer screening, as the age of 50 at which it should first be performed, and as the age of 45 years at which it should be performed first in the case of a family history

To obtain a total score for the first part of the questionnaire, if 100% of the answers a group gave to a question were correct, then that question received a score of 1. Thus, for each group, the total score was calculated as the sum of the scores for the questions: method of selection of screening, start of screening, and start of screening in the case of a positive family history (value range: 0–3).

A significantly higher total score was found in workers in a tertiary than in workers in a secondary hospital (tertiary: 1.74, secondary: 1.58, p = 0.007) and in those who receive a net monthly income of more than 1000 euros, than those who receive less than 1000 euro (≥ 1000 euro: 1.79, < 1000 euro: 1.61, p < 0.001). Also, a significant difference was found in the total score between the work groups (physicians: 1.90, administrative: 1.54, other paramedical staff: 1.53, nurses: 1.65, p < 0.001) and the educational level (masters/doctorate holders: 1.76, secondary graduates: 1.52, tertiary graduates: 1.78, p < 0.001), while no significant differences were found depending on the specialty category (laboratory specialty: 1.84, pathological specialty: 1 .95, surgical specialty: 1.83, p = 0.237), marital status (married: 1.67, other (single, divorced, widowed: 1.74, p = 0.168) and years of work (0–5 years: 1.68, 5–10 years: 1.81, ≥ 10 years: 1.70, p = 0.118) (Table VIII).

Table VIII

Total scores regarding colon cancer related answers with classification of the employees

Then for each group, the total score was calculated as the sum of the scores for the questions: method of screening selection, initiation of screening, initiation of screening in the case of a positive family history combined for colorectal cancer and prostate cancer screening (value range: 0–6), and its percentage was extracted.

A significantly higher overall score was found in tertiary hospital workers than in secondary hospital workers and those receiving a net monthly income of more than 1000 euros than those receiving less than 1000 euros. Also, a significant difference was found in the total score between work groups, specialty categories, and educational levels. In contrast, no significant differences were found according to marital status and years of work (Table IX).

Table IX

Percentage of total scores regarding colon cancer-related answers with classification of the employees

Regarding the implementation of the screening, the following results were obtained: of the 485 men, 21.5% (104) underwent colonoscopy, and of the 985 women, 19.3% (190), with no significant difference between them (p = 0.367). No significant difference was found between men and women who tested due to symptoms (men: 56.7% (59), women: 57.5% (112), p = 0.965), and men and women with a positive family history (males: 8.1% (39), females: 10% (98), p = 0.274). A significant difference was found in the average age of examination implementation between them (men: 45.42 (±9.4), women: 41.49 (±9.1), p = 0.001). For the whole population, a significant difference was found between the average age of examination (with or without symptoms, with or without positive family history) and due to symptoms (general population: 42.88 (±9.4), symptomatic: 39.38 (±9.48), p < 0.001) and between average age in general and average age with a positive family history (general: 42.88 (±9.4), positive family history: 45.35 (±7.51), p = 0.009). Therefore, there is a significant difference between the average age at which the respondents had a colonoscopy compared to 50 years (p < 0.001), while if they had a positive family history, they did it around the age of 45, without a significant difference (p = 0.719). Regarding the correct or incorrect application of their knowledge, no significant difference was found in the average age of examination of those who correctly answered when they should have a colonoscopy for screening and those who answered incorrectly (correct: 43.65 (±10.52), error: 42.21 (±8.57), p = 0.216), similar to the case of a positive family history (correct: 44.53 (±9.04), error: 45.77 (±6.85), p = 0.598) (Table X).

Table X

Average age of colonoscopy of all respondents is based on the presence or absence of symptoms and positive family history

| Reason for examination | Average age of colonoscopy implementation |

|---|---|

| Absence of symptoms/ positive family history | 42.88 |

| Because of symptoms | 39.38 |

| P-value | < 0.001 |

| Due to a positive family history | 45.35 |

| P-value | 0.009 |

A significant difference was found in the average age of implementation between single, divorced, or widowed and married (other: 39.15 (±11.87), married: 43.38 (±8.71), p = 0.004), while it was not found in the case of a positive family history (other: 42.5 (±9.17) married: 46.39 (±6.62), p = 0.076).

Additionally, a significant difference was found in the average age of implementation between workers up to 5 years, from 5 to 10 years and over 10 years (< 5: 35.3 (±9.7), 5–10: 35.52 (±11.11), > 10: 44.18 (±8.72), p < 0.001), similar in the case of a positive family history (< 5: 37.25 (±14.43), 5–10: 37 (±6.06), > 10: 46.62 (±6.21), p = 0.003).

Discussion

Our sample included 1470 workers in 5 hospitals who answered questionnaires about colorectal cancer. The respondents tended to answer both based on their knowledge and on their application in prevention. Regarding colon cancer, 94.3% (1377) answered that the test of choice is colonoscopy. 47.3% (641), the majority, believe that the appropriate age is 50 years. A significant difference in the response rate was found between the over- and under-40 age groups, with a higher proportion in the over-40 age group. Significant differences were found in the percentages of respondents among medical, nursing, administrative, and other paramedical staff who answered that the starting age for screening is 50 years and the starting age in the case of a positive family history screening is 45 years, with physicians having a higher percentage. The percentage of physicians practicing a pathological specialty who answered that the start of screening is 50 years was significantly higher than the percentages of laboratory and surgical specialties. At the hospital level, regarding the knowledge about the prevention of colon cancer, significant differences were found in the percentages of correct answers given by the respondents among the 5 hospitals: the examination of choice for the prevention of colon cancer is the colonoscopy, which had the highest percentage for Thebes General Hospital, and the age at which the above examination must be performed for the first time is 50 years in Heraklion University General Hospital. Among secondary and tertiary workers, considering the percentages of correct answers to the fact that the age at which the above examination should be conducted for the first time is 50 years, tertiary workers answered more successfully. In processing the responses to create a total score, a significantly higher total score was found in tertiary than secondary hospital workers and in those receiving a net monthly income of more than 1000 euros than those receiving less than 1000 euros. Also, a significant difference was found in the total score between the occupational groups, with a better score of physicians, and the educational level, with a better score of tertiary graduates. Regarding screening, a significant difference was found in the average age of colonoscopy implementation between men and women, with men’s average age being closer to 50. For the entire population, a significant difference was found between the average age of testing (with or without symptoms, with or without a positive family history) and due to symptoms and between the average age in general and the average age with a positive family history. In the remaining sub-categories, a significant difference was found in the average age of implementation between the single, divorced, or widowed and married, with the latter being closer to 50 years, in the average age of implementation among workers up to 5 years, from 5 to 10 years and over 10 years, with the latter being closer to 50 years.

In a similar series study, carried out at the Alexandra General Hospital with the participation of 237 workers (aged 55 ±4 years), it was found that 30% had undergone a colonoscopy (37% of men and 26% of women), while for preventive reasons, the figure was 17% [23]. In our study, 21.5% (104) of men and 19.3% (190) of women had undergone colonoscopy; however, a direct comparison between the two is impossible, as we did not exclude people under 50 years of age in our study. In this study, as in ours, they concluded that educational level plays an important role in screening compliance [23].

In another series study, questionnaires were given to asymptomatic physicians working in the National Health System aged 45–67 years [24]. The sample of 782 subjects consisted of 456 men and 326 women with an average age of 58 ±9 [24]. The average age of our sample was 43.52 ±10.16 years, and the male to female ratio was 484 and 985, respectively [24]. Of these, 49% belonged to a pathological specialty, 24% to surgery, and 27% to a laboratory specialty, but unfortunately, we are not given more information, beyond the percentages, making comparison difficult [24]. Of the 782 individuals, 34.2% (267) had undergone a colonoscopy for prevention, more specifically from the 45–50 age group 20.9% (49), while from 50–67, 39.7% (217) had undergone the examination [24]. The rates in our study are lower; however, direct comparison is difficult due to not using age as an exclusion criterion in our study. The average age at colonoscopy was 42.88 ±9.4 years [24]. The only possible correlation here would be that people over 40 answered correctly with a difference in age of first colonoscopy, possibly suggesting a small connection between knowledge in our study and implementation in the study we cited [24].

Another comparison worth making is with a study carried out in the Netherlands [25]. It involved 354 physicians specializing in gastrointestinal diseases (82% gastroenterologists and 18% gastrointestinal surgeons) and 126 general practitioners (11% in an academic structure and 89% in small hospitals) [25]. The average age of the former was 48 years (28–71), while of the latter, 49 (28–71). 92% of gastrointestinal specialists and 51% of general practitioners were in favor of screening, and 95% and 30%, respectively, intended to undergo a colonoscopy [25]. 72% of gastrointestinal specialists prefer colonoscopy, as do 27% of general practitioners. About 42% of specialists consider the age of 55 to be appropriate to start, while 29% of general practitioners consider 50 [25]. The way of approaching these results would help if we considered that there is a bold parallel with the Greek tertiary and secondary hospitals. Thus, it appears that 44.2% of workers in a secondary institution consider the age of 45 suitable for starting a colonoscopy, while 49.7% of workers in a tertiary institution consider the age of 50 (although without a statistically significant difference). This could lead us to the conclusion that in larger structures workers tend to believe that screening should start at an older age. Also, in our study, there is a small upward deviation of the average age of colonoscopy in tertiary hospitals (without a statistically significant difference). In addition, in our study, workers in a tertiary hospital answered correctly about the age of their first colonoscopy with a significant difference from workers in a secondary hospital (tertiary: 49.7%, secondary: 34.6%, p = 0.00004). It therefore appears that workers in tertiary and/or specialist hospitals have slightly better knowledge and possibly compliance with colorectal cancer screening [25].

Another study with which interesting comparisons could be made is a series study with questionnaires about the prescribing and referral habits of 211 physicians, who were involved in the operation of primary care units throughout Greece [26]. Of these, there were 105 men, and 94 women, with an average age of 32 years (24–62) [26]. The specialties were 31 specialist general practitioners, 22 intern general practitioners, 25 specialist pathologists, 53 intern pathologists, and 78 non-specialists. In our study, the average age was older, 43.52 (±10.16) years [26]. Also, the proportion of men and women differed (485 and 985 respectively), while our sample contained workers in tertiary and secondary hospital institutions and did not consist only of physicians [26]. Of the workers in the above study, 50% recommended screening for colon cancer in the patient’s routine check-up. Of these, 48% consider that finding blood in the stool and 23% that sigmoidoscopy has a preventive value for the detection of malignancy. 53% believe that screening (endoscopic or checking for fecal blood) should be done after the age of 50, while only 4% would recommend the endoscopic method. In our study, 94.3% consider colonoscopy as the method of choice [26].

It seems, therefore, that physicians who work in primary health structures do not consider screening as a priority in the patient’s examination, in view of our study with workers in larger structures. Also, a very small percentage of them prefer the endoscopic method, contrary to the large percentage that emerged from our research [27].

Finally, it is necessary to note that the modernization and updating of the health system is considered of utmost importance. As mentioned in the Lopez et al. study, it would be useful to exchange knowledge between the physicians of different specialties and the nurses from different clinics, in the context of information about the guidelines in the prevention and treatment not only of malignancies, but also of common diseases and complications that are treated in daily clinical practice. Also, a database of the insured could be created by gradually filling in their background information (personal and family) and informing them by text or when they visit the hospital about when they should undergo screening tests. This would help both chronic and regular monitoring, as well as the treatment of patients on an urgent basis, as well as changing the mindset of the general population [28].

To our knowledge, the current study is the first one to investigate and compare data about the knowledge and practical persistence of workers in the public healthcare system of Greece, regarding the screening of colorectal cancer. This survey, despite its strengths, also has some limitations. First of all, the time dedicated to each department/clinic was at most 3 days. In this context, some of the workers who could have participated might not have been able to do so due to their absence (different shifts, days off, etc.). In addition, because the questionnaires were mainly not distributed in person, as the majority of the departments do not have a meeting point, the workers who participated may be those who really care and are concerned about colorectal cancer screening. Despite the aforementioned limitations, we believe that our results genuinely reflect the current situation regarding colorectal cancer screening in the Greek healthcare system. In addition, our study is easily reproducible.

Conclusions

In this study, it was investigated whether the workers in health structures know and apply the preventive tests that should be carried out based on the guidelines for the prevention of colon cancer. The size of the sample and the possibility of comparing the results of our study with similar studies helped us to form a relatively comprehensive picture based on the initial questions of the paper and led to the search for ways and practices of improvement. In conclusion, the population examined belongs to the staff of secondary and tertiary hospitals. It does not represent the general population of the country, but it is a segment of it that one would expect to have more knowledge and a more positive response to colorectal cancer screening. The majority of respondents, due to their position, are familiar with and aware of the risks of malignancy and the importance of prevention. However, the possibility of improving their knowledge, and by extension that of the general population, exists and must be realized. Pillars for improving knowledge and compliance around screening are knowledge, inter-specialty communication, and health system outreach.