INTRODUCTION

Secondary trauma exposure as an occupational risk

A considerable number of professionals whose roles involve interaction with individuals who have experienced traumatic events are susceptible to adverse consequences arising from their professional engagement with such individuals. These consequences may be reflected in symptoms of secondary traumatic stress (STS). Figley [1] defines STS as stress resulting from helping or wanting to help a person who has experienced trauma or is suffering. He describes it as “natural, consequent behaviors and emotions resulting from knowledge about a traumatic event experienced by another person” (p. 10).

Reactions constituting STS, similar to those in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – which may occur in individuals directly exposed to trauma – include symptoms related to intrusion, avoidance, negative changes in cognition or mood, and increased arousal and reactivity [2]. Severe and persistent symptoms of STS may lead to the development of secondary traumatic stress disorder (STSD).

It is worth noting that some symptoms of STS are similar to other effects of work-related stress, including burnout and compassion fatigue. These have been documented among professionals engaged in social care, particularly within the healthcare sector [3]. The term vicarious traumatization, proposed by McCann and Pearlman [4], is also used to describe reactions to negative information received from traumatized clients. Despite the fact that a considerable number of studies have been conducted over the past thirty years on the effects of secondary trauma exposure, relatively few of them have focused on police officers, among whom Polish studies have indicated a relatively low intensity of STS [5, 6].

The relationship between resilience and job satisfaction with secondary traumatic stress

A multitude of factors have the capacity to influence the occurrence of STS. These factors can be categorised into two distinct groups: firstly, those related to the nature of the work performed, and secondly, individual characteristics of the person. Of these two factors, the latter are considered to be of greater importance. Some of these factors seem to protect the individual from developing STS symptoms. The significant role of individual factors in the occurrence of negative consequences of secondary trauma is highlighted by the Ecological Framework of Trauma proposed by Dutton and Rubinstein [7]. Among these factors, the authors mention personal and professional resources (including education, professional experience), individual susceptibility (personal trauma history), job satisfaction, and work contentment. The importance of resources, both work-related and personal, for the good and effective functioning of employees is also highlighted by the Job-Demands Resources Theory (JD-R) [8].

One of the factors that seems to be linked to STS is psychological resilience. This term refers to a multidimensional construct related to the ability to cope with stress [9, 10]. Resilience can be understood as a process, which involves the individual’s ability to detach from highly stressful life events and regain balance after a temporary breakdown resulting from a crisis. It can also, as Block and Block [11] suggest, be viewed as a personality characteristic, or according to Fredrickson [12], as a personal resource. Resilience allows for more effective coping with stress and negative emotions, promotes persistence and flexible adaptation to life’s demands, facilitates mobilization to take corrective actions in difficult situations, and increases tolerance for negative emotions and failure [9, 10].

Studies conducted in this area – though relatively few in number – have confirmed a negative relationship between resilience and STS. These have been shown among nurses [13, 14], therapists [15], and medical rescue personnel [16]. In other studies, also conducted among nurses, resilience partially mediated the relationship between STS and burnout [17]. For police officers, studies indicate negative relationships between resilience and PTSD [18, 19]; however, there is a lack of data on the association between STS and resilience in this professional group.

Job satisfaction has been identified as a factor associated with STS. This phenomenon impacts various domains of an individual’s functioning, influencing attitudes towards work, employee engagement and effectiveness. Notably, job satisfaction has been shown to play a crucial role in mitigating the adverse consequences of exposure to trauma, as well as reducing the magnitude of these consequences. The ecological model of trauma developed by Dutton and Rubinstein highlights the key role of job satisfaction in preventing the negative effects of secondary trauma exposure [7].

The term job satisfaction is often equated with job contentment, but these concepts are not synonymous. Job contentment, as indicated by Zalewska [20], is treated as an attitude toward work, an evaluation of the extent to which the work performed is beneficial (or detrimental) to the individual, and is expressed in affective reactions and cognitive evaluations. The cognitive aspect of job contentment is referred to as job satisfaction, while the emotional aspect is described as the emotional evaluation of work, workplace well-being, or mood at work. It should be emphasized that satisfaction is a subjective category, dependent on an individual’s perception. Therefore, it can be assumed that job satisfaction is what an employee perceives and evaluates as valuable and stemming from their needs.

A limited number of studies have been conducted on the relationship between job satisfaction and STS among professionals exposed to indirect trauma. Furthermore, among the studies that have been conducted, some focus on satisfaction derived directly from helping others rather than on the overall sense of job satisfaction. The results of analyses, the majority of which pertain to nursing staff, indicate a negative relationship between satisfaction from helping [21], job satisfaction [22, 23] and STS. Other studies [24] have shown that job satisfaction was a significant factor in reducing the severity of STS symptoms among intensive care nurses.

However, there are also studies that did not confirm a relationship between job satisfaction and STS symptoms [15, 25]. In a study conducted among medical staff it was found that the relationship between job satisfaction and STS was mediated by cognitive trauma-coping strategies [23] and by social support [26].

The presence of ambiguous data underscores the necessity for additional research in this domain. Furthermore, such analyses are conspicuously absent among Polish police officers exposed to secondary trauma. This issue appears to be of significance, as research indicates that approximately two-thirds of police officers in Poland experience job satisfaction and are committed to their organisation [27]. Job satisfaction may, therefore, serve as a significant factor in preventing the negative effects of secondary traumatization.

It is also worth noting the potential positive correlations between resilience and job satisfaction. Research by Potocka and Waszkowska [28] indicates that as available work resources and personal resources increase, job satisfaction also grows. Strong positive relationships between work resiliency and job satisfaction have been demonstrated in studies of Egyptian engineers [29]. The link between resilience and job satisfaction has also been identified in studies of Czech workers employed in helping professions [30]. Therefore, it can be assumed that resilience helps professionals working with trauma survivors enhance their job satisfaction, thereby reducing the negative effects of secondary exposure to trauma.

The research presented here aimed to establish the relationships between psychological resilience, job satisfaction, and STS symptoms among police officers exposed to secondary trauma. The following research questions were explored:

What is the level of STS, resilience, and job satisfaction in the studied group of police officers?

Are variables such as gender, age, police division, overall work experience in the police force, experience working with trauma survivors, and workload with traumatized clients associated with the severity of STS?

Are resilience and job satisfaction related to the severity of STS?

Are resilience and job satisfaction related to each other?

Does job satisfaction mediate the relationship between resilience and STS?

METHODS

The research was conducted between December 2023 and October 2024. Special permission to carry out the study was obtained from the Chief Police Headquarters. A total of 237 Polish police officers participated, including trainees of the professional officer training program. Of the participants, 220 officers (92.82%) reported that as part of their duties, they had contact with individuals who had experienced traumatic events – the results from this group were included in the analyses. These officers represented two divisions of the police: prevention (n = 120; 54.5%) and criminal (n = 100; 45.5%). The age of the participants ranged from 22 to 59 years (M = 39.08; SD = 7.00). Men (n = 183; 83.18%) outnumbered women (n = 35; 15.91%), with two respondents (0.91%) not specifying their gender. The overall length of service in the police ranged from 2 to 32 years (M = 14.55; SD = 6.27), and the length of service working with trauma-exposed individuals ranged from 1 year to 32 years (M = 12.01; SD = 6.18). The workload, expressed as the estimated percentage of work time dedicated to directly helping traumatized clients, ranged from 2% to 100% (M = 34.07; SD = 26.18).

The individuals with whom the police officers had contact during their service experienced various types of traumatic events. The most common ones included: death, including the death of a close person (n = 88), suicides, suicide attempts (n = 51), and accidents (n = 47).

The study used a questionnaire developed for the purposes of this research, as well as three standard measurement tools, the characteristics of which are presented below. It is also worth noting that the questionnaire included questions regarding the length of service, experience of working with individuals affected by trauma, as well as the officer’s personal exposure to such situations.

To measure the symptoms of secondary traumatic stress, the Secondary Traumatic Stress Inventory (STSI) was used, developed by Ogińska-Bulik and Juczyński [15]. It consists of 20 statements (e.g., “To what extent did recurring, distressing, and unwanted memories of clients’ stressful events occur?”), each rated by the participant on a 5-point scale, where 0 indicates “not at all” and 4 indicates “very strongly.” A total score of 33 or higher on the inventory may indicate a high probability of secondary traumatic stress. These statements describe symptoms that fall under the four criteria of PTSD, including intrusions, persistent avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, negative changes in cognitive and emotional areas, and increased arousal and reactivity. In the current study, Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.83.

To assess psychological resilience, the Resilience Measurement Scale – SPP-25, developed by Ogińska-Bulik and Juczyński [9] – was used. It allows for the measurement of resilience understood as a personality trait. The scale consists of 25 statements (e.g., “I make efforts to cope regardless of how difficult the problem is”), to which the participant responds using a scale ranging from strongly disagree (0 points) to strongly agree (4 points). These statements fall under five factors: 1) persistence and determination in action, 2) openness to new experiences and a sense of humor, 3) personal competencies to cope and tolerance of negative emotions, 4) tolerance of failure and viewing life as a challenge, and 5) an optimistic attitude towards life and the ability to mobilize in difficult situations. Cronbach’s a coefficient is satisfactory (0.89).

The Job Satisfaction Scale is a tool used to assess job satisfaction. It is a modified version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale by Diener et al. [31] which was originally designed to assess overall life satisfaction. The Polish version of this scale was developed by Zalewska [20]. It consists of 5 statements related to the cognitive evaluation of work (e.g., “In many ways, my job is almost ideal”). Respondents use a seven-point scale (from 1 – “Strongly agree” to 7 – “Strongly disagree”). All statements form a unidimensional structure, Cronbach’s a coefficient is 0.86.

RESULTS

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. The distribution of results for the variables included in the study deviated from normal, therefore non-parametric tests were applied, namely the Mann-Whitney U test, to examine differences between means and Spearman’s rho in order to determine relationships between variables. To assess the mediating role of job satisfaction, a mediation analysis was conducted using the bootstrapping procedure.

The results indicate a relatively low level of STS in the studied group of police officers exposed to secondary trauma. Using the criteria established for STS, it was found that 83% (n = 181) of the surveyed officers experienced a lower level, while 17% (n = 37) reported a higher level of secondary traumatic stress.

Gender did not differentiate the level of STS (men: M = 17.59; SD = 14.92, women: M = 15.67; SD = 14.68). Similar results were obtained for the police officers’ service units, i.e., the police division (prevention: M = 18.16; SD = 15.96, criminal division: M = 17.00; SD = 14.34). Age (rho = 0.013; p > 0.05), overall length of service in the police (rho = 0.048; p > 0.05), experience working with trauma survivors (rho = 0.061; p > 0.05), and workload (rho = 0.04; p > 0.05) were not related to the overall level of STS.

The mean obtained on the SPP-25 scale (M = 79.33) corresponds to a value of 7 sten, which indicates a high result. The mean of satisfaction with work score obtained by the police officers (M = 22.25) can be classified as moderate. It is similar to the values obtained in validation studies conducted among four groups of employees [20], as well as among medical personnel working with trauma survivors (M = 21.28) [23] (Table 1).

The data presented in the table indicate that STS is negatively correlated with both psychological resilience (rho = –0.238) and job satisfaction (rho = –0.249; p < 0.05). Similar negative correlations were also found between resilience and STS symptoms such as avoidance (rho = –0.163; p < 0.05), changes in cognition and emotions (rho = –0.223; p < 0.05), and changes in arousal and reactivity (rho = –0.276; p < 0.05). Only the symptoms of intrusion do not correlate with resilience. Furthermore, resilience was positively correlated with job satisfaction (rho = 0.355; p < 0.01).

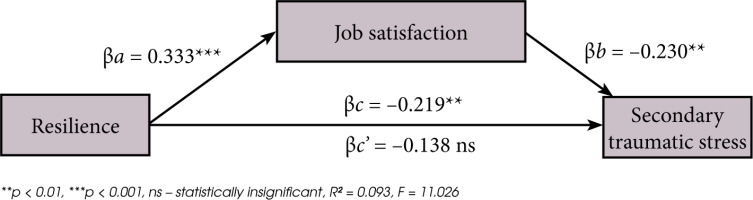

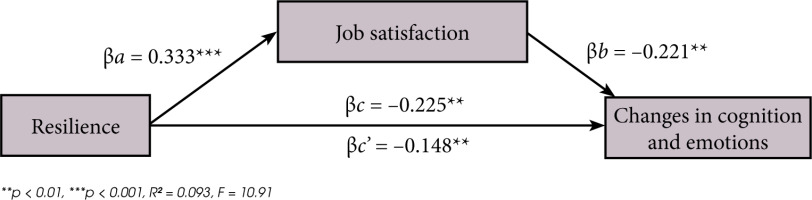

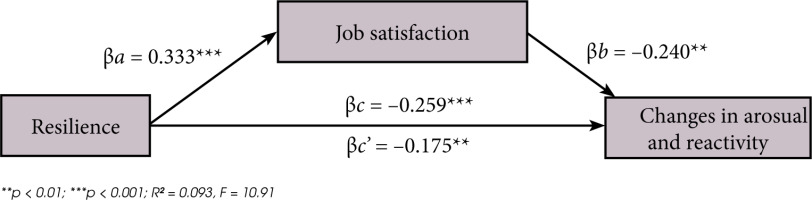

In the next step, it was examined whether job satisfaction mediates the relationship between resilience and STS and its symptoms. A mediation analysis was conducted using the bootstrapping procedure proposed by Preacher and Hayes [32]. This type of analysis allows for the establishment of a more complex model structure, in which the explanatory variable acting as a predictor (in this case, resilience) is related to the dependent variable (here: overall STS and its specific symptom categories) through a third variable, acting as a mediator (here: job satisfaction). Mediation occurs when the mediating variable reduces the predictive value of the independent variable (predictor) on the dependent variable. A 95% confidence interval was adopted for the analysis. For each path in the mediation models, standardized β coefficients were calculated. Five models were constructed, three of which were statistically significant (Figures I-III).

Resilience is positively correlated with job satisfaction and negatively with STS, meaning that the higher the resilience, the higher the job satisfaction and the lower the intensity of STS symptoms. Job satisfaction is negatively correlated with STS. Introducing job satisfaction as a mediator results in the relationship between resilience and STS becoming statistically insignificant. This indicates full mediation and suggests that job satisfaction has a stronger association with STS compared to resilience.

Moreover, it was found that job satisfaction partially mediates the relationships between resilience and two criteria of STS symptoms, namely negative changes in cognition and emotions, and increased arousal and reactivity. In this case, introducing job satisfaction as a mediator weakens the relationship between resilience and STS, but it remains statistically significant.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of the analyzed variables (n = 220)

DISCUSSION

The police officers participating in the study, who work with individuals experiencing trauma, demonstrate relatively low levels of STS. These levels are lower compared to other professional groups working with traumatized individuals, particularly medical personnel, as assessed by the same tool [15]. A significant majority of respondents, namely 83%, showed relatively low risk for the development of secondary traumatic stress disorders. On the other hand, 17% exhibited a high risk for such disorders. Similar results have been reported in other studies involving Polish police officers exposed to secondary trauma [5, 6].

Figure I

Job satisfaction as a mediator in the relationship between resilience and secondary traumatic stress (STS)

Figure II

Job satisfaction as a mediator in the relationship between resilience and changes in cognition and emotions

Figure III

Job satisfaction as a mediator in the relationship between resilience and changes in arousal and reactivity

In the present study, sociodemographic and work-related variables were controlled. None of these variables – gender, age, police division, years of service in the police, years of working with trauma-affected individuals, or workload – were statistically significantly associated with the severity of STS. Psychological resilience, like job satisfaction, was negatively correlated with STS, which aligns with expectations. This indicates that as resilience and job satisfaction increase, the severity of STS decreases. However, it should be noted that these correlations are relatively weak.

The data obtained regarding the relationship between resilience and STS in the group of police officers align with the Job Demands-Resources (JDR) model [8], which emphasizes the significant role of resources in human functioning in the workplace. The findings are consistent with those of studies conducted on other groups of professionals working with individuals who have experienced traumatic events [13, 14, 16].

The results indicating negative relationships between job satisfaction and secondary traumatic stress are consistent with the aforementioned model by Dutton and Rubinstein [7] as well as data presented in the literature [21, 22, 24]. Job satisfaction was found to be a full mediator of the relationship between psychological resilience and STS (total score) and a partial mediator in the relationship between resilience and two symptom criteria of STS, namely, negative changes in cognition and emotions, and heightened arousal and reactivity. This suggests that both variables, i.e., resilience and job satisfaction, which are positively correlated, can protect police officers exposed to secondary trauma from developing STS symptoms, with slightly greater importance attributed to job satisfaction.

It is important to acknowledge the relatively weak correlation between resilience and job satisfaction, and the negative consequences of trauma exposure in the study’s police officer sample. This suggests that other factors (not included in the study) may have a greater impact on the severity of STS. Additionally, it cannot be ruled out that the role of individual traits as a protective factor against the negative effects of work-related stress may be somewhat overestimated.

The study has certain limitations. It was cross-sectional in nature, which does not allow for conclusions about the causality of the relationships observed. The sample of police officers studied was not very large, which excludes the possibility of generalizing the results to the entire population of police officers working with individuals who have experienced trauma. The majority of respondents were men. Furthermore, the analyses did not take into account the nature or timing of the traumatic events experienced by clients, nor the traumatic events experienced by the officers themselves. It is worth noting that police officers dedicate only a portion of their work to assisting individuals who have experienced trauma. Additionally, the Job Satisfaction Scale used in the study allowed for a general assessment of job satisfaction in the police force, rather than satisfaction specifically related to working with individuals who have experienced trauma.

Despite its limitations, the findings of this study provide valuable insights into the factors influencing the negative effects of indirect trauma exposure among Polish police officers. The study confirmed the role of resilience and job satisfaction in preventing symptoms of STS and reducing the risk of STSD. It is distinguished by its focus on a rarely studied occupational group – police officers – and the use of a new tool for measuring STS, namely the Secondary Traumatic Stress Inventory, based on DSM-5 criteria.

The results obtained may serve as an inspiration for further research into the role of other individual characteristics, such as empathy or work engagement, in mitigating the negative consequences of indirect trauma exposure. Longitudinal studies would also be valuable, to analyze changes in the intensity of STS over time.

The results obtained can be used to develop preventive programs for police officers working with individuals who have experienced trauma, through which officers could, among other things, develop traits that contribute to psychological resilience. Resilience not only reduces the occurrence of STS symptoms but also helps in better coping with future challenges. Paton et al. [33] proposed a model for developing and shaping resilience among police officers, referencing Antonovsky’s [34] concept of resilience, which suggests that officers’ ability to give meaning, coherence, and manageability to difficult events reflects the interaction of factors related to the individual, the team, and the organization. Increasing job satisfaction also seems crucial, as it may not only alleviate STS symptoms but also improve the efficiency of task performance.

CONCLUSIONS

The results obtained allowed for the formulation of the following conclusions:

Police officers exposed to indirect trauma exhibit relatively low levels of STS.

Sociodemographic and work-related variables (gender, age, police department, total length of service in the police, length of service working with individuals who have experienced trauma, workload related to traumatized clients) are not associated with the severity of STS.

Resilience and job satisfaction are negatively correlated with STS.

Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between resilience and STS.

Resilience and job satisfaction may serve as protective factors against the negative consequences of indirect trauma exposure; however, job satisfaction appears to play a slightly greater role.