INTRODUCTION

There is an established overlap between disordered eating behaviors and alcohol misuse, with estimates suggesting that 20-39% of people reveal comorbid disordered eating and alcohol consumption [1-3]. Individuals diagnosed with eating disorders and eating difficulties are four times more likely to meet alcohol-related disorders criteria [4]. Specifically, alcohol consumption is a predictive factor for bulimia rather than anorexia [5]. In addition, excessive alcohol consumption may exacerbate eating disorders [6]. Given the important relationship between problematic alcohol use and inappropriate dietary patterns, alcohol intoxication may be associated with more frequent eating disorders and negative alcohol- related consequences.

One behavioral pattern that has been identified is referred to as drunkorexia [7] and is characterized by disordered eating behaviors and alcohol misuse occurring in tandem [8]. Specifically, people knowing that they will consume alcohol adopt behaviors aimed at limiting or compensating for calories consumed with alcohol. Compensatory behaviors include excessive physical exercise, purging, vomiting, or a reduction in the caloric content of meals during the day [9], both before and after alcohol consumption. Due to the introduction of dietary restrictions, alcohol intake does not necessarily cause an excessive fear of weight gain. This phenomenon has also been described as alcoholimia [10] and food and alcohol disturbance (FAD) [11]; however, in this article, we will refer to it as drunkorexia.

No clear diagnostic criteria for drunkorexia have been established, as the condition falls between eating disorders and alcohol misuse or dependence. Thompson- Memmer et al. [10] identified specific characteristics of drunkorexia, suggesting that it is more closely related to bulimia than anorexia. These authors considered the following to be behaviors associated with drunkorexia: consumption of 4-5 servings of alcohol within two hours, a strong link between self-esteem and body image, the presence of compensatory behaviors, such as use of diuretics, purging, vomiting, excessive physical exercise, meal skipping or caloric restrictions, the co-occurrence of these behaviors at least once a month for at least three consecutive months and the absence of dysfunction during bulimia. Caloric restriction and excessive physical activity may occur as compensatory behaviors either before or after alcohol consumption, further complicating diagnosis. The characteristics of this disorder point to the behavioral factors, while the lack of diagnostic criteria may present a problem in determining when a person requires professional help [8]. While identifying specific behaviors may aid the diagnosis of drunkorexia, it is still essential to identify behavioral, emotional, and cognitive patterns associated with the analyzed disordered eating behavior.

Several motives for engaging in drunkorexia behaviors have been indicated [12]. One primary reason is the desire to maintain weight despite providing the body with “empty calories” contained in alcoholic beverages. Interviews with young adults revealed that some of them engaged in drunkorexia behaviors to appear slimmer and, thereby, more attractive [13]. To achieve this, they may restrict meals, use laxatives, or engage in excessive physical exercise. Another motive is experiencing the effects of alcohol more rapidly and intensely as a result of compensatory behaviors [10]. At the same time, the risk of weight gain is reduced. Social motives are also important. The studies showed that social anxiety, especially fear of negative evaluation, and pressure from peers are predictive factors of drunkorexia behaviors among adolescents and young adults [14, 15].

Additionally, drunkorexia can also serve as coping strategy related to emotional dysregulation [16]. Indeed, research indicates that difficulties in emotion regulation and disordered eating patterns are associated with both drunkorexia behaviors and post-drinking compensation [17]. Moreover, emotional dysregulation has been found to moderate the relationship between anxiety and drunkorexia – higher levels of emotional difficulties were connected with higher psychological distress and stricter caloric restrictions during alcohol consumption among adolescents [18]. Overall, individuals may attempt to manage their emotions through irregular eating patterns, alcohol consumption, and compensatory behaviors. However, these actions maintain or increase emotional dysregulation over time.

As research in the area of drunkorexia is in its early stages, further clarification of this construct, including the motivations behind drunkorexia behaviors and predictors of their occurrence is required. This will, in turn, inform the direction of future therapeutic interventions. The relatively low prevalence of drunkorexia causes a lack of awareness regarding the link between alcohol intake and eating disorders. As a result, individuals often pursue therapeutic interventions for one of these goals without considering the other. This study examines whether drunkorexia may occur in the non-clinical population of young people.

The variety of behaviors associated with drunkorexia and the numerous motives behind such behaviors suggest the existence of different trajectories, particularly in relation to disordered eating or excessive alcohol consumption.

In this study, we investigated drunkorexia patterns in a nonclinical population. As part of our first objective, we examined eating behaviors and alcohol use among individuals with and without drunkorexia. We hypothesized that individuals with drunkorexia will report significantly higher levels of disordered eating symptoms and alcohol-related problems compared to individuals without drunkorexia. The second objective was to explore the motivational and behavioral predictors of drunkorexia. This exploratory aim sought to identify the specific motives and behaviors that contribute to the prediction the severity of drunkorexia. The third aim was to generate profiles of individuals with drunkorexia based on the intensity of various behaviors related to the condition.

METHODS

Measures

Demographics

Six items asking about gender, age, height, weight, subjective health assessment (5-point Likert scale where 1 means very unhealthy and 5 means very healthy), and subjective health care (5-point Likert scale where 1 means not taking care of health and 5 means taking care of health intensively).

Alcohol dependence

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT [19, 20]) is a screening tool that determines the level of alcohol use (harmful, hazardous, and likely dependent drinkers). It consists of two parts, i.e., a history of alcohol consumption (10 items; score between 0-4) and a clinical assessment performed by a specialist. In this study, only the first part of the test was used. The test result determines the severity of the disorder. A score ≤ 7 points indicates low-risk alcohol consumption, a score of 8-15 shows hazardous alcohol consumption, a score of 16-19 indicates harmful drinking, and a score ≥ 20 points indicates likely alcohol dependence. The internal consistency of the tool in this study was α = 0.77.

Eating disorders

EAT-26 Test (Eating Attitude Test-26 [21]) is a questionnaire that assesses the risk of eating disorders. The test consists of 26 items. The subjects respond to each item on a four-step Likert scale. A score > 20 suggests food-related problems. The test includes three subscales: Dieting, Bulimia and Food Preoccupation, and Oral Control. The internal consistency of the whole scale was α = 0.84 (Dieting α = 0.82, Bulimia and Food Preoccupation α = 0.80, and Oral Control α = 0.63).

Drunkorexia

Compensatory Eating and Behaviors in Response to Alcohol Consumption Scale (CEBRACS [22]) is used to measure behaviors in drunkorexia (restriction of meals before alcohol consumption, overexercising or purging) over three periods of time (before, during, and after alcohol consumption). The questionnaire consists of 21 items. The subjects respond to each item on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The Polish adaptation is developed by Celban, Różycka, and Stefanek (in preparation). The cut-off for clinical use is a score above 21 points – the higher the scores are, the greater the intensity of the symptoms. The factorial analysis revealed four sublevels, i.e., Alcohol Effect (eating-related behaviors to achieve higher alcohol consumption effect), Bulimia (impulsive compensatory behaviors using various forms of purging), Dietary Restraint and Exercise, and refusal to consume meals and other restrictions). The internal consistency of the whole scale was α = 0.91, and for each subscale, the α value was as follows: α = 0.94 for Alcohol Effect, α = 0.33 for Bulimia, α = 0.91 for Dietary Restraint and Exercise, and α = 0.40 for Restriction. The subscales were included for further analysis due to the satisfactory reliability of the whole scale. However, interpretations of the Bulimia and Restriction subscales should be treated with caution.

Drunkorexia Motives and Behaviors Scale (DMBS [12]) is a set of tests that allows the identification of behaviors that coexist with drunkorexia, and the identification of motives for undertaking such behaviors. In the absence of the Polish version of the scale, the translation and adaptation procedures were conducted by Celban, Różycka, and Stefanek (unpublished). The set consists of four subscales:

Drunkorexia Motives and Behaviors Scale consists of 23 items on a Likert-type scale ranging from never (1), almost never (2), sometimes (3), almost always (4) to always (5). It includes two factors: Drunkorexia Motives (11 items, α = 0.84), related to the reasons why individuals engage in drunkorexia and Drunkorexia Behaviors (12 items, α = 0.96) connected with different behaviors associated with drunkorexia. It includes the following subscales: Enhancement (drinking for fun and happiness, e.g., “I drink because it is fun”), Social Motives (drinking to feel comfortable in social situations or because it is welcomed, e.g., “I drink to be liked,”), Conformity Motives (drinking due to other people, e.g., “I drink to fit in with a group I like”). The internal consistency coefficients were satisfactory for Enhancement (α = 0.85), Social (α = 0.73), and Conformity motives (α = 0.72). In the initial stages of the factor analytic process, a four-factor with items associated with the coping strategies was proposed. However, the items had psychometric properties (α < 0.5) that excluded them from the final model. The Behavior Scale consists of Eating Restriction (entering the limits of calories due to earlier drinking, e.g., “In a day I plan to drink, I control the amount of calories by eating less fat”, α = 0.96) and Compensatory Behaviors (engaging in behaviors to counter weight gain, e.g., “In a day I plan to drink I control the amount of calories by exercise more than usual”, α = 0.94).

Drunkorexia Fails Scale (DFS) refers to behaviors adopted when a person fails to undertake actions compensating for calories consumed with alcohol before or after drinking. It consists of the Approach subscale (further alcohol consumption regardless of its effect on body weight) and the Avoidance subscale (avoiding further alcohol consumption due to the predominant motive of weight control). The internal consistency of the scale was α = 0.77 (Approach α = 0.74; Avoidance α = 0.67).

Drunkorexia During an Alcohol Consumption Event (DDACE) indicates typical behaviors and thoughts that accompany a person while drinking alcohol. It consists of two subscales, i.e., Drinking Behaviors (a change in terms of alcohol-related behaviors connected with the type, amount, and frequency of alcohol consumption) and Calories (a change in calorie intake). The internal consistency of the whole scale was α = 0.61 (α = 0.60 for Drinking Behaviors and α = 0.49 for Calories). Due to low values, the results of the analyses should be treated with caution.

Post Drinking Compensation Scale (PDS) refers to actions taken after drinking alcohol to reduce the effect of alcohol on body weight, e.g., engaging in physical exercise, inducing vomiting, and limiting meals. The internal consistency was α = 0.89.

Participants and procedure

The participants were recruited in the region of Upper Silesia, Poland, through the online research participation program via the snowball method. The inclusion criteria required an age above 18 and a declaration of alcohol consumption. The exclusion criteria were the formal diagnosis of alcohol dependence or eating disorders.

For the purposes of this questionnaire survey, each person was informed that it was a part of a voluntary and anonymous study. The participants provided informed consent and completed the questionnaires online. All procedures were approved by the authors’ university Ethics Committee (90R/02.2021).

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Statistica 13 and JASP (Jeffrey’s Amazing Statistics Program version 0.18.3.0). For all statistical tests, we considered an α level of 0.05 to be significant. The first aim was to test the hypothesis that individuals with drunkorexia, compared to those without, would report significantly higher disordered eating symptoms and alcohol-related problems. To test this hypothesis, we compared the groups with and without the features of drunkorexia using the Kolmogorov- Smirnov test. The second (exploratory) aim was to investigate the motivational/behavioral predictors of drunkorexia severity as measured by CEBRACS. A four-step hierarchical regression was performed. The third aim was to generate profiles of people with drunkorexia, based on the intensity of various related behaviors. K-means cluster analysis was used in the drunkorexia group to identify the profiles of people with a characteristic set of traits. In order to compare the clusters with drunkorexia symptoms from CEBRACS, alcohol intake, and eating disorders symptoms, the Mann-Whitney U test was conducted.

RESULTS

Prevalence of drunkorexia

A total of 286 respondents participated in the study (231 women; Mage = 24.238; SDage = 5.978, 55 men; Mage = 24.581, SDage = 7.629; age range: 18-67 years). 33 participants were excluded due to an incorrectly completed questionnaire, giving the total sample of 253 participants. To achieve the first aim, we used the cut-off point of the CEBRACS questionnaire (> 21 points), which defines the diagnosis of behaviors typical of drunkorexia [23]. The pattern was shown in 43% of the research group (108 people out of 253). The details about the drunkorexia group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics for the participants who exceeded the cut-off, indicating presence of drunkorexia (n = 108)

[i] AUDIT – Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, EAT-26 – Eating Attitudes Test, CEBRACS – Compensatory Eating and Behaviors in Response to Alcohol Consumption Scale, DMBS – Drunkorexia Motives and Behaviors Scale, DFS – Drunkorexia Fails Scale, DDACE – Drunkorexia During an Alcohol Consumption Event, PDCS – Post Drinking Compensation Scale

Differences between groups with and without drunkorexia

To achieve the first aim and test the hypothesis that individuals with drunkorexia have significantly more drinking- and eating-related problems, two groups were formed according to the cut-off: one with drunkorexia (43%, n = 108) and the other without drunkorexia (57%, n = 145). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to compare whether the groups significantly differed when it came to the variables of interest. The variables that differentiated the groups at statistically significant levels were as follows: weight, problems related to alcohol use on the AUDIT scale, Dieting from EAT-26, Alcohol Effect, Dietary Restraint and Restriction from the CEBRACS, Enhancement and Social Motives from DMBS (with Social Motive as significantly higher in drunkorexia group), as well as Eating avoidance and Compensatory behaviors from DMBS. In the group of people with drunkorexia, enhancement motives were significantly less frequent. However, social motives and behaviors coexisting with drunkorexia, such as eating avoidance and compensatory behaviors, were more prevalent. In addition, individuals with drunkorexia showed food avoidance significantly more frequently when the calorie limit was exceeded, and they also adopted more compensatory behaviors. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Differences in behaviors and attitudes between the risk group of drunkorexia and without the drunkorexia pattern

AUDIT – Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, EAT-26 – Eating Attitudes Test, CEBRACS – Compensatory Eating and Behaviors in Response to Alcohol Consumption Scale, DMBS – Drunkorexia Motives and Behaviors Scale, DFS – Drunkorexia Fails Scale, DDACE – Drunkorexia During an Alcohol Consumption Event, PDCS – Post Drinking Compensation Scale

Predictors of drunkorexia

A hierarchical linear regression was performed to test the relative contribution of variables of interest to the prediction of drunkorexia (as measured by the CEBRACS total score) as a third aim of the research. Step 1 included demographic variables, step 2 – the characteristics of alcohol consumption, as measured by the AUDIT total score, step 3 – the characteristics of the disturbed eating pattern as measured by the EAT-26 subscales, and step 4 – variables directly related to drunkorexia. In step 2, higher severity of alcohol consumption (β = 0.371, p < 0.001) increased the proportion of the variance explained in the model. In step 3, the characteristics of eating disorders, particularly dietary restrictions (β = 0.232, p < 0.001) and control of food intake (β = 0.164, p < 0.001) were significant predictors. In step 4, in addition to alcohol consumption and dietary restrictions, alcohol avoidance after breaking the rules (β = 0.142, p < 0.05), compensatory behaviors during (β = 0.279, p < 0.001) and after alcohol intake (β = 0.271, p < 0.001), the social motive of drunkorexia-related behaviors (β = 0.130, p < 0.05) and food avoidance (β = 0.344, p < 0.001) also increased the proportion of the variance explained. The inclusion of predictors in the last step significantly increased the amount of the variance explained by the model (R2 = 0.63, F(16,210) = 24.697, p < 0.001). The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Hierarchical regression analysis with demographic variables (gender and BMI), severity of alcohol use (AUDIT total score), disordered eating behaviors (EAT-26 subscales), and drunkorexia-related variables (DMBS subscales, DFS subscales, DDACE subscales and PDCS regressed on the total score on the CEBRACS

AUDIT – Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, EAT-26 – Eating Attitudes Test, CEBRACS – Compensatory Eating and Behaviors in Response to Alcohol Consumption Scale, DMBS – Drunkorexia Motives and Behaviors Scale, DFS – Drunkorexia Fails Scale, DDACE – Drunkorexia During an Alcohol Consumption Event, PDCS – Post Drinking Compensation Scale

Profile analysis of individuals with drunkorexia

The fourth aim was to check the possible profiles of drunkorexia behaviors in the subsample of individuals who exceeded the CEBRACS cut-off for drunkorexia. The cluster analysis using the K-means method was performed in the drunkorexia group, assuming the presence of two clusters. Additional analyses showed no presence of different constellations. The Silhouette coefficient showed a good fit (0.6), despite the unequal groups.

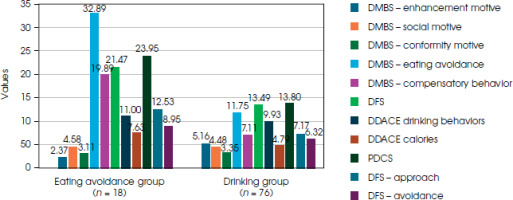

The cluster analysis revealed two distinct clusters: Eating Avoidance and Drinking Cluster (Figure I). The variance analysis is reported in Table 4. Individuals in the Eating Avoidance Group (n = 18) achieved lower scores only in terms of enhancement motive to drink alcohol. The group showed high scores on behaviors related to weight control, such as consumption of low- calorie meals and exercising. The level of compensatory behaviors during and after drinking was higher than in the second cluster. This group also scored higher on approaching alcohol despite the calories and weight control, the enhanced effect of alcohol consumption by changing eating behaviors and changing calories intake. Disturbed eating patterns were the central dysfunction axis in this group. Individuals presenting this pattern showed the tendency to consume alcohol while controlling calorie intake and conducting a range of compensatory behaviors for weight control. Apart from significantly lower enhancement motives, no motive for alcohol consumption emerged as statistically significant in this group. Individuals in the Drinking Cluster (n = 76) demonstrated statistically significant higher enhancement motives for drinking. All the other variables had, on average, lower scores than those in the Eating Avoidance Cluster. There was no clear pattern of eating disorders.

A group comparison was conducted between the Eating Avoidance and Drinking groups. The median of each group and the results of Mann-Whitney U tests are shown in Table 5. The eating disorder group was statistically significantly higher in drunkorexia scores than the drinking group. The AUDIT scores and the EAT-26 scores were insignificant. There were also significant differences in Enhancement Motive, Eating Avoidance, Compensatory Behaviors, Calories Approach, and Post-drinking compensation.

Table 4

Mean clusters and variance analysis

Table 5

Mann-Whitney U test between Eating Avoidance group and Drinking group on study measures

AUDIT – Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. EAT-26 – Eating Attitudes Test. CEBRACS – Compensatory Eating and Behaviors in Response to Alcohol Consumption Scale, DMBS – Drunkorexia Motives and Behaviors Scale, DFS – Drunkorexia Fails Scale, DDACE – Drunkorexia During an Alcohol Consumption Event, PDCS – Post Drinking Compensation Scale

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study was to examine the relationship between drunkorexia and associated behavioral patterns (maladaptive eating behaviors, dysfunctional alcohol consumption), and to compare these behaviors among individuals with and without drunkorexia. In addition, potential predictors of drunkorexia severity have been examined, and typical drunkorexia-related behavior profiles have been determined.

It has been observed that 43% of the research group have exhibited drunkorexia characteristics, which is notable given the nonclinical nature of the group. This is in line with the data from the studies by Choquette et al. [24] – 55% and Blackstone et al. [25] – 62.4% participants, and Simons et al. [26] – 56.9% participants from the drinking and non-drinking groups. A review by Berry et al. [27] found that between 37.6% and 49.3% of college students who drink alcohol engage in drunkorexia at least 25% of the time when they consume alcohol. The most frequent drunkorexia behaviors reported were skipping meals [28] and dieting [29], which is in line with our results.

Among individuals with drunkorexia patterns, the most significant behaviors observed were alcohol use, dietary restrictions, eating avoidance, compensatory behaviors, and motives related to alcohol enhancement or social approval. These behaviors were notably different from those found in respondents without drunkorexia. Given the mean age of participants, we speculate that drunkorexia behaviors are common among young people seeking social approval. The data revealed that individuals with drunkorexia tendencies often reported drinking more than average, paid close attention to calorie intake, and considered compensating for alcohol-related calories. Similarly, Laghi et al. [18] found a negative correlation between effective social functioning and drunkorexia patterns.

Several variables contributed to explaining the variance in drunkorexia, mainly restriction, over-exercising, and/or purging before, during, and/or after drinking alcohol. Specifically, the inclusion of general problems related to alcohol, general caloric restrictions, social motives for restricting caloric intake while drinking, restricting calories before/during/after drinking, as well as changing alcohol-related behavior during an alcohol consumption event was significantly related to the severity of drunkorexia, controlling for all the other variables in the model. The overall model explained over 60% of the variability in drunkorexia severity. As previously mentioned, Berry et al. [27] identified two key motives behind drunkorexia: caloric compensation and alcohol enhancement due to reduced caloric intake. On the one hand, people cut calories; on the other, reduced caloric intake intensifies the effect of alcohol. While we speculate that disordered eating behaviors might be secondary to alcohol consumption issues, the cross-sectional design of this study prevents us from drawing definitive causal relationships. Recent studies suggest that the association between drunkorexia for alcohol enhancement and drinking frequency varies based on the time of drunkorexia behaviors. When they occurred before drinking, there was a positive association, negative if they occurred while drinking, but if drunkorexia behaviors occurred after drinking, there was no association [30, 31].

The results of group comparisons and the regression analysis indicate a consistent pattern of abnormal eating behavior and potentially problematic drinking behavior among individuals with drunkorexia found in previous studies [5, 9, 10]. The problematic alcohol use in that group may be related to both the need for intoxication and the suppression of thoughts about extra calories. These findings can be interpreted in light of social approval and willingness to adjust to people of similar age, sharing similar problems [10, 11, 32] or inadequate emotion regulation strategies [30].

Alcohol use may act as a coping strategy [33], especially if the predominant need is to improve one’s functioning in social relationships, obtain approval, and arouse positive emotions in others. In other words, meal control and alcohol consumption are not an indicator of independence or autonomy in young people [7, 10]. People with drunkorexia seem to drink and limit calorie intake to be part of a group. Alcohol intoxication may enhance social skills and lower the tension or anxiety connected with meeting people. It seems that alcohol intake may act as a strategy for emotion regulation in drunkorexia [17, 34]. As Ward and Galante [12] said, reducing calorie intake is a cost of the proper self-image for the group. It is also possible that the effect of intoxication allows people to forget about their daily life problems (avoidance strategy) and, above all, about the total calories consumed throughout the day [35].

Berry and her team [27] suggested that people with drunkorexia have two primary motives: to enhance the effects of alcohol and/or to compensate for alcohol-related calories. As drunkorexia represents a functional relationship between disordered eating and alcohol abuse behaviors rather than just a co-occurrence of these behaviors, they concluded that it is necessary to assess the presence of both of these health risk behaviors to identify their antecedents, consequences, and trajectory accurately. Multifinality and varying correlates likely result from divergent needs that motivate a given behavior.

Furthermore, similar to other studies [33] clear characteristics of eating disorders were found in the drunkorexia group which scored higher on the eating disorder subscales, dietary restraint due to wish to enhance the effects of alcohol consumption and engaging in various compensatory strategies during and after drinking to control weight. Given many psychological issues, such as dissatisfaction with one’s body, low self-esteem, and perfectionism occurring in people with eating disorders [36], studies show that they are more likely to abuse various substances, including alcohol. However, these are the means to achieve social approval (not necessarily under group pressure but resulting from the internal motivation of individuals). The results obtained from the model may suggest drunkorexia is an independent psychological construct with elements of eating disorders as well as alcohol abuse.

A cluster analysis identified two distinct profiles among individuals exhibiting drunkorexia behaviors: one with a dominant eating disorder (ED) pattern and another with more pronounced drinking behaviors (DB). The ED group showed a clear focus on weight and calorie control, engaging in compensatory behaviors like restricting food, exercising, vomiting, and drinking without pleasure. In contrast, the DB group had stronger motives for drinking but less focus on food restriction and weight control despite still displaying drunkorexia behaviors. This suggests drunkorexia is not homogenous, with disordered eating as a common base but two potential developmental paths. The ED group was small, limiting interpretation, but it may reflect more severe cases, while the DB group could represent a milder or earlier stage of the disorder. Previous research supports links between drunkorexia and alcohol consumption patterns, including frequency and alcohol use disorder [23, 37, 38]. Considering that people with drunkorexia report greater alcohol-related consequences than those who deny it [26, 37], alcohol- related interventions may be useful for reducing alcohol- related harm among people with DB patterns. The cluster analysis seems to be in line with the conclusions of Berry et al. [27] that the enhancement motive is often present but underrated in the drunkorexia pattern.

LIMITATIONS

The present study is not without its limitations. First, due to its cross-sectional nature, it is impossible to draw cause-and-effect conclusions from the variables tested. The functional relationship between eating and alcohol issues is essential, so longitudinal research is necessary. Second, the small sample size and varied age of the respondents make it impossible to generalize conclusions for the entire population. Therefore, the results should be verified using a larger sample. Moreover, some questionnaires describing behaviors related to drunkorexia had low reliability, which limited the possibility of drawing definite conclusions. The group was in an average healthy weight range, which may restrict broader interpretations in non-normal weight groups with more pronounced eating difficulties. The research group mainly consisted of women, so it may be a characteristic pattern for women only, as they represent prevalence in eating pathology [39, 40]. Finally, even though the online version of the survey may not be suitable for drawing clinical diagnoses, but only for screening, the above observations set the direction for future, more extensive research.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study highlights the need to educate and support individuals who find it hard to cope with the challenges posed by their environment or the pressures of the slim body culture. The incidence of drunkorexia among adolescents and young adults is relatively high, indicating a need for more research in this area. Given its prevalence, more discussion of the mechanisms for developing abnormal eating patterns, education on eating disorders, and raising awareness of the negative consequences of alcohol abuse, combined with dietary restrictions may be warranted among adolescents and young adults.

This study broadens the understanding of the phenomenon of drunkorexia with the indication of characteristic behaviors. Further research may provide a starting point for the diagnosis of eating patterns in the context of drinking alcohol. The understanding of motivational factors related to drunkorexia can help identify therapeutic targets for patients and therapists. Identifying behavioral and motivational features of drunkorexia is a step toward the differentiation between drunkorexia and other eating disorders. The study highlighted the diversity of behaviors associated with drunkorexia. It is known that individuals who eat fewer meals before alcohol consumption to avoid weight gain are more likely to have eating disorders, while those who want to reach higher levels of intoxication are more likely to struggle with the problem of alcohol dependence in the future [7]. People who consume alcohol and engage in disordered eating behaviors may be screened for drunkorexia by mental health providers and physicians so that high-risk individuals may be identified early and treated with therapy. Depending on the addressed behaviors, it is possible to implement an appropriate approach focused on the treatment of nonspecific eating disorders or addiction therapy.