INTRODUCTION

Interleukins (ILs) are secreted proteins which regulate intracellular communication and keep many cellular functions under control, especially in terms of the immune response. Human genome encodes over 50 ILs and proteins related to them. In 1979, during the Second International Lymphokine Workshop in Switzerland the name “interleukin” was chosen in order to systematize medical nomenclature concerning this expanding group of cytokines [1, 2]. IL-5 is a 115-amino acid long cytokine, which in its active form is a homodimer. Along with IL-3, IL-4, IL-9, IL-10, and IL-13, it is produced by T helper 2 (Th2) lymphocytes. Other sources are mastocytes, basophils and eosinophils. IL-5 production can be stimulated by superantigens such as ones secreted by Staphylococcus aureus [3].

IL-5 plays a crucial role in immunological response, first of all in parasitic infestations. This cytokine works synergistically with IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), is responsible for terminal differentiation, activation and survival of committed eosinophil precursors, coordinates diversifying and releasing of eosinophils into circulation and extends their lifespan, cooperates with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), intensifies proliferation and differentiation of basophils, and promotes class switching of immunoglobulins (Igs) to IgA. Furthermore, it stimulates wound healing along with soft tissue remodeling [4].

IL-5 acts on target cells by binding to its specific receptor – IL-5R. This receptor consists of the subunit α (IL-5Rα), also known as a cluster of differentiation 125 (CD125), and the subunit β (IL-5Rβ). The β chain is bigger, contains a large cytoplasmic domain and is crucial for signal transduction. Although playing immeasurably different roles, they are both required in order to activate a successful IL-5 signal. Triggering of a signal is followed by its transduction which runs as per few major transduction pathways (JAK-STAT pathway, mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway – MAPK/ERK pathway, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway – PI3K pathway). The JAK-STAT signaling pathway communicates information from the outside environment to the nucleus of the cell. It activates genes through transcription using three main components: Janus kinases, signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins and receptors binding chemical signals. When a ligand binds to the receptor and phosphates are added by JAKs, STAT proteins bind to these phosphates and form a dimer during a process called phosphorylation. Then the dimer goes to the nucleus, binds to DNA and transcription of specific genes begins. The disruption of JAK-STAT signaling may result in disorders concerning the immune system such as asthma [4]. The MAPK/ERK pathway communicates a signal from the outside of the cell, using a receptor on its surface, to the nucleus. The pathway consists of many mitogen-activated protein kinases which communicate using phosphate groups that are added to other proteins. The function of this pathway involves cell cycle regulation, cell migration, wound healing and tissue repair. It also stimulates angiogenesis. Although the dysregulation of this pathway is mostly known to cause cancer, it may result in inflammation or developmental disorders. The PI3K pathway is an intracellular pathway related to growth, differentiation, proliferation, motility, and the cell cycle in general. PI3Ks are intracellular enzymes capable of phosphorylating and signal transducing. Some isoforms of PI3K regulate immune response and disturbance of this process results in immune diseases [5].

IL-5 plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of many allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (AR), asthma, angioedema, urticaria, and atopic dermatitis (AD). There is a significant increase in the number of eosinophils in blood, respiratory tract tissue and sputum in the process of these afflictions/diseases/disorders. Inhibition of this IL, using anti-IL-5 therapy agents such as benralizumab, mepolizumab and reslizumab, can be used for the treatment of plenty of eosinophilic diseases [6–8]. Additionally, over the last few years there has been some research into whether IL-5 facilitates the recovery of cardiac dysfunctions post myocardial infarct since it mediates the development of eosinophils that are essential for tissue post-injury repair [9].

As shown above, IL-5 has enormous potential and understanding of its functioning may help in treating not only atopic diseases. In this research paper we would like to focus on describing and emphasize the meaning of IL-5 in regard to AR, angioedema, urticaria, AD, and asthma.

METHODS

A comprehensive review of the scientific literature was conducted using the PubMed database, focusing on studies involving IL-5 in allergic diseases. Findings regarding IL-5 levels, their correlation with symptom severity, and the impact of IL-5-targeted therapies were assessed. Sources included peer-reviewed articles, clinical trials, and case reports, published in English. The study adopted a time criterion, limiting the inclusion of scientific publications to those published in the last 10 years. We also included older studies due to the lack of newer studies in the scientific database. We used keywords such as: “interleukin 5”, “allergic diseases”, “allergic rhinitis”, “angioedema”, “urticaria”, “atopic dermatitis”, “asthma”, “benralizumab”, “reslizumab”, and “mepolizumab”.

RESULTS

Analyzed studies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Summary of the literature review on the role of IL-5 in the pathogenesis of allergic diseases

| Study | Allergic disease | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Luo et al. [13] | AR | CD4+ T cells from patients with AR showed lower expression of FasL compared to CD4+ T cells from patients in the control group IL-5 inhibits FasL expression, which increases Bcl2L12 levels in CD4+ T cells Bcl2L12 binds to the FasL promoter, preventing transcription of the FasL gene, which impairs the apoptotic mechanism Inhibition of Bcl2L12 restores normal apoptotic mechanism in CD4+ T cells from AR patients |

| Beeh et al. [14] | AR | No seasonal AR patient had IL-5 detected in sputum Plasma IL-5 concentration increased after allergen challenge A significant positive correlation was found between the relative increase in sputum ECP and changes in plasma IL-5 concentration in some responders/patients |

| Garrelds et al. [15] | AR | IL-5 was detectable in nasal lavage of patients with AR to house dust mites In these patients, house dust mite extract challenge resulted in immediate nasal symptoms and increased IL-5 levels (early phase response) After 3.5–8.5 h post-challenge, symptoms returned and IL-5 levels increased (late phase response) |

| McDermott et al. [16] | AR | Intranasal instillation of moderate doses of allergen in patients with seasonal AR caused the occurrence of symptoms and an increase in IL-5 concentration |

| Leaker et al. [17] | AR | Nasal late allergic reaction to grass pollen elevated the IL-5 level in some patients In individuals who experienced an increase in IL-5 and IL-13 levels in their nasal mucosal lining fluid following a challenge with an intranasal allergen, an increase in the expression of genes related to eosinophils, type 2, neutrophils, IL-1, and circadian rhythm was observed |

| Usami [20] | Angioedema | Case report of a 28-year-old woman with non-episodic angioedema associated with eosinophilia, who presented with peripheral edema of the extremities and elevated serum IL-5 levels in laboratory tests |

| Hirmatsu-Ito et al. [21] | Angioedema | Case report of a 31-year-old lactating woman with non-episodic angioedema associated with eosinophilia, who presented with peripheral edema of the extremities and elevated serum IL-5 levels in laboratory tests |

| Murakami et al. [22] | Angioedema | Case report of an 18-year-old male with episodic angioedema and eosinophilia syndrome who presented with monthly episodes of angioedema, pruritic nodules, weight gain, and fever lasting twelve years. Elevated levels of IL-5 were observed during the episodes Corticosteroid treatment resulted in clinical improvement and decreased serum IL-5 levels |

| Gomułka et al. [8] | Urticaria | In patients with CSU, significantly higher mean serum IL-5R concentrations were found compared to the control group Mean serum IL-5R concentrations did not correlate with pruritus intensity |

| Antosz et al. [28] | Urticaria | Mepolizumab treatment of a 27-year-old woman with asthma and CSU led to complete control of CSU |

| Antonicelli et al. [30] | Urticaria | Mepolizumab treatment of 3 women aged 35–39 years suffering from both CSU and SEA led to complete resolution of skin symptoms within a few days after the first dose of the drug The improvement in clinical condition was maintained throughout the observation period (6 months) |

| Altrichter et al. [31] | Urticaria | Blood eosinophil levels decreased in CSU patients after 24 weeks of benralizumab therapy No significant differences in CSU symptom control were observed between placebo-treated and benralizumab-treated patients |

| Gomułka et al. [8] | AD | A significant positive correlation was found between the level of IL-5R and the severity of AD measured by SCORAD |

| Oldhoff et al. [35] | AD | Treatment with mepolizumab did not prevent the occurrence of an eczematous reaction induced by the atopy patch test in patients with AD |

| Ichiyama et al. [37] | AD | Case report of a 57-year-old woman with AD and asthma whose treatment with mepolizumab and benralizumab improved asthma symptoms but did not reduce the symptoms of AD |

| Farne et al. [38] | Asthma | Anti-IL-5 therapy reduced asthma exacerbations and slightly improved FEV1 No serious adverse events were observed with this therapy |

| Kandikattu et al. [41] | Asthma | IL-5 plays a key role in eosinophil differentiation and development, participating in the pathogenesis of asthma IL-5 inhibits eosinophil apoptosis by inducing BCL-XL via NF-kB IL-5 signal transduction involves JAK-STAT-p38MAPK-NFkB activation, which results in extracellular matrix remodeling, EMT, and immune response |

| Pelaia et al. [43] | Asthma | IL-5 is involved in airway remodeling Treatment against IL-5 reduced the thickness of the reticular basement membrane by decreasing the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins |

[i] AD – atopic dermatitis, AR – allergic rhinitis, CSU – chronic spontaneous urticaria, ECP – eosinophilic cationic protein, EMT – epithelial–mesenchymal transition, FEV1 – forced expiratory volume in 1 s, IL-5 – interleukin 5, IL-5R – interleukin 5 receptor, SCORAD – Scoring Atopic Dermatitis Index, SEA – severe eosinophilic asthma.

DISCUSSION

THE ROLE OF INTERLEUKIN 5 IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF ALLERGIC RHINITIS

Researchers discovered that sensitizing the nasal mucosa in Brown Norway rats with ovalbumin significantly increased IL-5 mRNA expression compared to non-sensitized controls. This indicates that IL-5 plays a critical role in the immune response and local inflammation in the nasal tissue following sensitization, highlighting its significance in allergic responses [10]. The findings revealed that IL-5 production was significantly elevated in mice with AR following the activation of ILC2 cells within the nasal-associated lymphoid tissue. This increase was associated with intensified eosinophilic inflammation and exacerbated allergic symptoms. The observed reduction in IL-5 expression following treatment with anti-major histocompatibility complex (anti-MHC) II or anti-CD4 antibodies suggests that IL-5 secretion by ILC2 cells is regulated by interactions between MHC II and CD4. This underscores the crucial role of IL-5 in inflammation associated with AR [11]. The study by Kim et al. demonstrated that IL-5, when combined with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), diminished the viability of olfactory sphere cells (OSCs) and significantly increased apoptotic expression. In contrast, IL-5 alone did not impact OSCs. This implies that IL-5 exacerbates apoptosis induced by TNF-α, underscoring its potential role in the damage to olfactory neural cells linked to AR [12]. According to Luo et al., IL-5 suppressed the expression of FasL and promoted the expression of Bcl2L12 in CD4+ T cells from patients with AR. This suppression led to a decrease in the apoptosis of these cells. The IL-5-driven upregulation of Bcl2L12 indicates its role in inhibiting normal apoptotic processes, which contributes to Th2 polarization and the persistence of allergic inflammation [13]. Nasal allergen challenges significantly increased plasma IL-5 levels, which were correlated with higher sputum eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) in some responders/patients. This suggests that IL-5 may contribute to systemic inflammation and eosinophilic activation following allergen exposure [14]. There is evidence that nasal exposure to a house dust mite extract elevates IL-5 levels in patients with AR, especially during the late-phase reaction [15]. Ongoing daily exposure to allergens in individuals with seasonal AR led to a sustained increase in IL-5 levels [16]. Researchers found that IL-5 is crucial in the late allergic reaction to grass pollen, with increased levels found in nasal samples of AR patients after allergen exposure. This highlights IL-5’s role in type 2 inflammation and suggests it could be a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for managing allergic reactions [17].

THE ROLE OF INTERLEUKIN 5 IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF ANGIOEDEMA

Angioedema is a medical condition that results in swelling of the hypodermic or submucosal tissue as a result of vascular enlargement and increase of permeability. Most often it manifests itself within a few minutes to several hours. It appears as asymmetric swelling in the eyelids, red zone of the lips, upper airways, gastrointestinal tract, genital region, and distal extremities [18]. We can divide the origin of angioedema with urticaria to allergic or non-allergic causes, and angioedema without urticaria. Allergens include medications, foods, latex, and Hymenoptera venom. Non-allergic edema can be caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, radiographic contrast agents or idiopathic reasons. Angioedema without urticaria can be associated with the correct amount of plasma C1-INH or with a deficiency of plasma C1-INH. There is an even more detailed division of angioedema with eosinophilia: episodic – Gleich’s syndrome, and non-episodic [19]. Usami described a case report of a patient with angioedema on distal parts of lower limbs, high levels of white blood cells (WBCs): first measurement at 12,700/μl and second 11,900/μl (proper/normal level 5,000–8,000/μl), high eosinophil percentage of 34.1 and 40.2 (proper/normal level 0–4.5), and IL-5 level at 11.0 pg/ml (reference/normal range, 0–3.9 pg/ml). In this particular case, oral use of prednisone 10 mg was a sufficient treatment [20]. Another case report was presented by Hirmatsu-Ito et al. of a 31-year-old lactating woman, who 4 months after giving birth, had developed prominent edema on both of her lower limbs and feet. She did not have any chronic conditions that could explain her current physical state. Laboratory test results showed elevation of WBCs from 18,200/μl, to 19,100/μl with 68.6% of eosinophils. All of the rheumatic immunological compound’s levels did not show any increase. Various causes of water retention in tissues were dismissed. That patient did not need any medication to regain full recovery. This paper focused on the correlation between edema and elevation of cytokines and chemokines including IL-5 that caused an increase of swelling. To come to the conclusion authors were using comparison of extracellular water (ECW) to total body water (TBW). They found a positive correlation between the level of IL-5 and intensity of edema (ECW/TBW) [21]. Another work was prepared by Murakami et al. who described the case of an 18-year-old man. He presented with skin rash, edema on both lower limbs and arms and eosinophilia. These symptoms persisted for 12 years. Diagnostics of neurological, rheumatic, cardiological and genetic diseases were performed, as well as ultrasound examination, bone marrow aspiration biopsy, and computed tomography, without obtaining a clear diagnosis. Skin biopsy showed epidermal edema and eosinophils located perivascularly. Laboratory tests showed WBC count of 22,200/μl with 40% of eosinophils, IgM level of 2,540 mg/dl and an elevated level of IL-5. The patient was diagnosed with eosinophilia syndrome. The treatment based on prednisolone and furosemide was initiated, achieving improvement in the clinical condition [22]. All case reports analyzed above show a connection between eosinophil levels and IL-5.

THE ROLE OF INTERLEUKIN 5 IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF URTICARIA

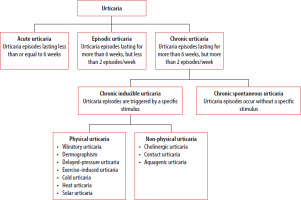

Urticaria is a condition characterized by the development of wheals (also known as hives: red, itchy skin eruptions of various shapes), angioedema, or both [23]. It is a common skin condition that affects up to 20% of the world’s population at some point in their life and must be distinguished from other medical conditions in which wheals, angioedema, or both may occur as features of a spectrum of clinical conditions, for example anaphylaxis, bradykinin-mediated angioedema, including hereditary angioedema [23–25]. The key step in urticaria is mast cell–basophil degranulation, which can occur immunologically or non-immunologically. Immunological activation can occur via type I/1 (associated with IgE), type IIa/2a autoimmunity (associated with IgM or IgG), or type IIb autoimmunity (associated with IgG) [23, 25, 26]. In type IIa/2a autoimmunity, IgG or IgM autoantibodies bind to the IgE or FcεRI receptor on mast cells, leading to degranulation [25]. The classification of urticaria is presented in Figure 1.

Patients with chronic urticaria (CU) may have more than one form of CU [23]. CU affects approximately 0.5–1% of the global population [25]. On the other hand, chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) affects about 0.5% of the population in Europe, and women are more commonly affected [27, 28]. Based on recent studies, the existence of two endotypes of CSU has been suggested – type 1 autoimmunity (associated with IgE) and type 2b autoimmunity (associated with IgG), in which different types of Th cells play a role in the pathogenesis [26]. Eosinophils also play an important role in the pathogenesis of CSU, acting synergistically with mast cells and mutually enhancing each other’s actions/activity [28, 29]. For these reasons, activities targeting IL-5 or IL-5R (IL-5R is present on eosinophils, basophils, and CD34+ precursor cells) may influence the course of CSU [28]. Benralizumab inhibits IL-5 receptor, and mepolizumab and reslizumab are IL-5 inhibitors [25].

BENRALIZUMAB AND CSU

A pilot study involving 45 participants (15 patients with AD, 15 patients with CSU, and 15 healthy controls) demonstrated that the mean serum IL-5R concentration was significantly higher in CSU patients compared to the control group (p = 0.038). At the same time, the mean serum IL-5R concentration did not correlate with the intensity of pruritus in the examined patients. On the other hand, the Urticaria Activity Score 7 (UAS7) and Chronic Urticaria Quality-of-Life Questionnaire Total Score (CU-QoL TS) values were significantly correlated after drug administration compared to baseline values and a notable improvement was observed in the CU-QoL TS components, particularly in scores related to pruritus/wheal and the impact of urticaria on physical activity, sleep, and leisure time [8]. In addition, the case of a patient suffering from CSU and severe eosinophilic asthma (SEA) with elevated blood eosinophil levels was described, in which benralizumab treatment led to an improvement in CSU symptoms (the case was reported by German researchers) [30]. In the study conducted by Altrichter et al., called “ARROYO”, which was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial lasting 24 weeks, 155 adult patients suffering from CSU were divided into three groups: two groups received benralizumab (30 mg or 60 mg), while the third group received a placebo. After 24 weeks of benralizumab therapy, a decrease in blood eosinophil levels was observed; however, no significant differences in CSU symptom control were noted between patients receiving placebo and those treated with benralizumab [28, 31]. A case report was also provided for a 59-year-old man with atopic asthma, AR, and CSU with a positive autologous serum skin test (ASST) and elevated blood eosinophil levels. CSU was well controlled with 180 mg fexofenadine (oral H1 antihistamine, UAS7 of 0–4), but despite high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), oral corticosteroids, montelukast, and long-acting β-agonist (LABA), asthma remained poorly controlled. Therefore, benralizumab (30 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks, then 30 mg every 8 weeks) was added, resulting in excellent asthma control and significant eosinophil reduction. However, after 3 months of therapy, episodes of severe urticaria and angioedema (UAS7 of 38) began occurring daily, leading to an increase in fexofenadine dosage without any significant benefit. Finally, benralizumab was discontinued, and upon discontinuation, the UAS7 score dropped from 32 to 6, allowing fexofenadine to be reduced to one tablet daily. Unfortunately, the mechanism underlying this case is not clear, but the induction of type II hypersensitivity by benralizumab is being considered [32]. It follows from the above that anti-IL-5R therapy (using benralizumab) may modify CSU symptoms (either alleviating or exacerbating them) or have no clinical effect.

MEPOLIZUMAB, RESLIZUMAB AND CSU

The case of a 27-year-old woman suffering from asthma and CSU with elevated blood eosinophil levels was described. Due to asthma, mepolizumab therapy was recommended for her (100 mg every 4 weeks). Before starting this therapy, CSU was poorly controlled, with disturbing exacerbations occurring without a clear cause or following infections. During treatment, the patient reported complete control of CSU, with no urticarial lesions, even during infections [28]. In the literature, 4 other cases of patients suffering from both CSU and severe eosinophilic asthma (SEA), treated with mepolizumab (3 patients) and reslizumab (1 patient) were described. One case was reported by German scientists, while the other 3 were described by Italian scientists and a British scientist. In the 3 patients (women aged 35–59 years) described by the Italian scientists and the British scientist, the skin symptoms completely resolved within a few days after the first dose of mepolizumab, and the improvement persisted throughout the entire observation period (the average observation period was 6 months). These cases suggest a significant phenotypic difference between CSU occurring as a separate disease and CSU coexisting with SEA [30]. On the other hand, a 60-year-old man with severe asthma, chronic sinusitis with nasal polyps, and episodes of generalized chronic urticaria was described. The patient was treated with a combination of oral glucocorticosteroids and ICS, LABA, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and omalizumab (a recombinant anti-IgE antibody), which suppressed urticaria symptoms and initially improved asthma control. After asthma control was lost, omalizumab was switched to mepolizumab, which resulted in recurrence of severe urticaria episodes despite regular treatment with fexofenadine. Therefore, combined immunological therapy (omalizumab + mepolizumab) was used, leading to improved asthma control and suppression of urticaria episodes. Next, the patient discontinued oral glucocorticosteroids and LAMA, reduced the dose of ICS, and continued treatment with omalizumab + mepolizumab, achieving asthma control, suppression of skin itching, and resolution of anaphylactic symptoms [29]. It follows from the above that anti-IL-5 therapy (with mepolizumab or reslizumab) may improve CSU symptoms in patients suffering from CSU and SEA, but not necessarily in other situations.

THE ROLE OF INTERLEUKIN 5 IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF ATOPIC DERMATITIS

AD is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory disease with an autoimmune basis. It is estimated to affect 1 in 5 children worldwide and approximately 3–10% of the adult population [8, 33]. It is characterized by skin dryness, pruritus, erythema, and the presence of papules and eczema. Depending on the patient’s age, lesions typically occur in specific areas, most often in the elbow and knee flexures, on the wrists, as well as on the face and neck in children [8, 34]. The pathogenesis of AD is complex, involving genetic, immunological, and environmental factors (e.g., allergens, stress, cold exposure). Key roles in AD are attributed to epidermal barrier dysfunction and disturbances in the skin microbiome. Damage to the epidermal barrier increases transepidermal water loss and skin permeability, making it more susceptible to allergens, bacteria, and environmental pollutants. Significant contributors to the development of AD include enhanced differentiation of CD4 lymphocytes and hyperactivation of the Th2 pathway, leading to elevated production of cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, and IL-13. Cytokines secreted by Th17, Th22, and Th1 lymphocytes, as well as mediators from damaged epidermal cells (e.g., IL-33 and IL-25), also play a role [8, 33].

Gomułka et al. conducted a study evaluating IL-5R levels in patients with AD. Among 15 AD patients, 3 had severe disease, while 12 exhibited moderate symptoms based on the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis Index (SCORAD). The results of the study revealed a significant positive correlation between IL-5R levels and clinical symptom severity. The authors suggested that blocking IL-5 or its receptor could be a potential therapeutic target for severe AD, especially in patients with elevated IL-5R levels. However, further studies are required to confirm the efficacy of such strategies [8]. Oldhoff et al. conducted a multicenter study in six European centers in 2002 to assess the efficacy of mepolizumab in treating AD. The study involved 43 AD patients, all experiencing disease exacerbations. Of these, 20 participants received mepolizumab, while 23 were given a placebo on days 0 and 7. Itching intensity was recorded using patient diaries, and eosinophil levels were measured at multiple time points. After 28 days, eosinophil levels were significantly reduced in the mepolizumab group compared to the placebo group. However, despite the reduction in eosinophil levels, there was no significant improvement in clinical symptoms in the treatment group [35, 36]. Ichiyama et al. reported the case of a 57-year-old woman with asthma and AD. The patient was treated with mepolizumab and benralizumab, which effectively alleviated asthma symptoms but did not improve the course of AD [37]. The potential use of IL-5 as a therapeutic target in AD remains under investigation. To date, no effective therapy directly targeting IL-5 has been developed. Further studies involving larger patient cohorts and higher drug dosages are necessary to determine whether IL-5 inhibition could be a viable therapeutic strategy for AD and whether its blockade could provide clinical benefits by reducing symptoms and disease exacerbations [8, 34–36].

THE ROLE OF INTERLEUKIN 5 IN THE PATHOGENESIS OF ASTHMA

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the respiratory system. The characteristic symptoms primarily include shortness of breath, a subjective sensation of chest tightness, wheezing, and coughing. The severity of these symptoms varies and results from variable airway hyperreactivity, leading to subsequent bronchial narrowing, which impairs the free flow of air to the alveoli. The natural course of the disease is marked by periods of exacerbation [38]. Asthma can be divided into several phenotypes, characterized by distinct clinical manifestations and varying responses to pharmacological treatment [39, 40]. In asthma, eosinophils are the cells involved in the body’s response to inflammatory signals [41]. Activation of eosinophils by IL-5 leads to the release of eosinophil peroxidase, major basic protein, leukotrienes, IL-13, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), among other substances. These mediators, released during degranulation, act within the airways, causing airway hyperreactivity and, at later stages, airway remodeling. These processes are responsible for the pathogenesis and clinical symptoms of asthma [42]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that IL-5 promotes airway eosinophilia and allergen-induced bronchial hyperreactivity. In patients with allergic asthma, elevated levels of IL-5 are observed in induced sputum and blood serum. A correlation has also been established between increased IL-5 levels in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and the severity of asthma [43].

CONCLUSIONS

This review presents the role of IL-5 and IL-5R in AR, angioedema, urticaria, AD, and asthma. Among these diseases, IL-5 and its receptor play the most significant role in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma, and benralizumab and mepolizumab help reduce disease symptoms. In contrast, in AD, IL-5 and IL-5R have little impact, and biologic drugs targeting IL-5 or IL-5R (mepolizumab and benralizumab) do not reduce its symptoms. However, IL-5 and IL-5R play a greater role in the pathogenesis of CSU than in AD; benralizumab, mepolizumab, and reslizumab can reduce symptoms in certain cases, though rarely. In angioedema with accompanying elevated eosinophil levels and in AR, elevated IL-5 levels have been observed. However, it remains unclear whether inhibiting IL-5 or IL-5R would reduce symptom severity in these diseases. The influence of IL-5 in one disease should not be dismissed simply because it has not been observed in another one. Likewise, its role in the pathogenesis of all allergic diseases should not be assumed solely based on its significance in a few ones. Therefore, IL-5 should be studied in the context of individual allergic diseases.