Introduction

The regenerative capacity of the liver has been studied in recent years using 2/3 partial hepatectomy or liver resection (LR), as it is called, in which 2/3 of the liver mass is resected [1]. 2/3 partial hepatectomy in rats was first described by Higgins and Anderson in 1931 [2]. Since then, several researchers have performed 2/3 partial hepatectomy in mice, and many perioperative parameters have been defined to form this experimental model [3, 4]. Apart from the surgical technique, the effects of anesthetics, circadian rhythm, food control, and mouse sex and age on regenerative activity have been considered. Liver regeneration begins immediately after liver tissue loss, and the metabolic state of the remaining hepatocytes, as determined by the previously mentioned factors, affects the dynamics of regenerative capacity.

Liver regeneration has been associated with signaling cascades such as in growth factors, cytokines, remodeling of the intercellular substance, and several feedback mechanisms [5]. Arterial blood supply does not change after 2/3 partial hepatectomy, whereas portal circulatory supply triples, leading to increases in pancreatic and intestinal cytokines such as insulin, epidermal growth factor, endotoxins, and food nutrients that are available to hepatocytes [6, 7]. The portal vein is the main blood supply route in the liver. After 2/3 PH, the blood in the portal vein that should supply the whole liver mass irrigates to the remaining 1/3 of the liver tissue. Therefore, the friction exerted by blood flow on the endothelial surface increases significantly and there is an increase in shear stress [8]. After partial hepatectomy, the remaining 1/3 of hepatocytes start a DNA synthesis cycle, which peaks at 36 h in mouse models, resulting in a mass equal to 60% of the original liver. A second, smaller fraction of cells initiates a second round of DNA synthesis, resulting in the recovery of the original hepatocyte count [9]. The regenerative process is completed in 5–7 days after partial hepatectomy in rodents [10].

Partial hepatectomy affects the liver-intestinal barrier and causes liver inflammation by activating the innate immune system via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [11, 12]. At least 11 types of TLRs have been discovered in humans (TLR1–11), as well as 13 types in mice. Apart from TLR2, which forms heterodimers with TLR1 or TLR6, the other TLRs induce homodimeric signaling, where two identical TLRs function as homodimers [13]. TLR signaling involves nuclear light chain transcription factors for nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) and induction of activator protein-1 (AP-1). These factors regulate a variety of genes that encode important pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins (IL-1-β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [14]. All TLRs, except for TLR3, utilize cytoplasmic proximal signaling intermediate primary myeloid differentiation protein 88 (MYD88), either alone or together with the Toll/IL-1 receptor adapter protein (TIRAP) [15]. Most members of the TLR family also transduce signals through a canonical pathway involving the interleukin-1 receptor-associated-kinase (IRAK) complex (Supplementary Figure S1).

Although the particular roles of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 in liver regeneration have been identified, the way that these molecules interact with each other, as well as the other signaling molecules that take part in liver regeneration, has not yet been demonstrated.

Aim

Therefore, the aim of the present experimental study was to investigate the expression of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6, as well as their connecting molecules, and their role in liver regeneration.

Material and methods

Animal model

Eighty male C57BL/6J mice 12–14 weeks of age and weighing 20–25 g were obtained from Harlan Laboratories, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN, USA). The mice were housed in individual cages in rooms with stable environmental conditions (18–21°C, 40–50% humidity, 12 : 12 h artificial day/night cycle), and were provided with food and sterile water ad libitum. Body weight, food consumption, and general health were monitored daily. The mice were randomly assigned into eight groups with 10 animals in each group. In the first four groups (LR12, LR24, LR36, LR168) a 2/3 partial hepatectomy (liver resection – LR) and abdominal wall closure were performed. Laparotomy and closure of the abdominal wall without hepatectomy (sham –Sh) were performed in the other four control groups (Sh12, Sh24, Sh36, Sh168) (Supplementary Figure S2).

Experimental procedure

The animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and oxygen flow (2 l/min). Skin disinfection was performed with 70% ethanol. A midline abdominal incision (approximately 3 cm long) was made, and the following surgical procedures took place: cross section of the falciform ligament, ligation at the base of the left lateral lobe (near the liver portal), ligation of the left lateral lobe placing the knot as close to the liver base as possible, cross section of the ligated lobe just above the suture, insertion of thread for the second knot between the stump and the middle lobe above the gallbladder, which was removed but no closer than 2 mm from the vena cava, cross section of the ligated medial lobe above the suture leaving an ischemic stump above the knot and a small piece of the irrigated medial lobe below it, and abdominal wall closure using continuous suture.

Postoperative analgesia was maintained by repeated subcutaneous injections of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) every 6 h for at least 2 days, or until the time of euthanasia for the groups that were sacrificed before 48 h, in both the LR and Sh groups. All mice underwent resuscitation with 1 ml of subcutaneously administered, pre-warmed (37°C) isotonic sodium chloride solution. The mice were returned to their cages immediately after the surgical procedures at a stable room temperature of 22°C with access to food and water.

The mice underwent blood sampling via cardiac puncture, euthanasia, and liver resection after 12 h (groups LR12 and Sh12), 24 h (groups LR24 and Sh24), 36 h (groups LR36 and Sh36) and 168 h (groups LR168 and Sh168). Liver specimens were obtained from the same liver lobe in all mice.

Laboratory tests

White blood cell (WBC) and red blood cell (RBC) counts were determined with a blood analyzer machine (Nihon Kohden, Japan). The following biochemical markers were also determined by the enzyme method: serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT), serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and γ-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT). Biochemical blood analysis was performed with a biochemical analyzer (Chemical Awareness Analyzer, Awareness Technology, Inc., Palm City, FL, USA).

Histology and immunochemistry

Parts of the 80 tissue specimens were immersed in a 10% formaldehyde solution and then paraffin-embedded for histological and immunohistochemical study. Continuous sections (5 µm in depth) throughout the liver tissue specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for the observation of inflammatory cells, hyperplasia, endothelial cells, and elastin levels. Corresponding sections of histological specimens were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for the tissue expression of Toll-like receptor 1 (TLR1 sc130896, Santa Cruz, 2 µg/ml, 1 : 200 dilution), Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2, ab47840, Abcam, 2 µg/ml, 1 : 200 dilution), Toll-like receptor 6 (TLR6 ab71429, Abcam, 2 µg/ml, 1 : 200 dilution), myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88 sc11356, Santa Cruz, 2 µg/ml, 1 : 200 dilution), interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4, MA5-15883, Invitrogen, 2 µg/ml, 1 : 200 dilution), Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adapter protein (TIRAP, ab17218, Abcam, 2 µg/ml, 1 : 200 dilution), and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B (NF-kB, p65 subunit, C terminus, PA5-16545, Invitrogen, 2 µg/ml, 1 : 200 dilution).

Immunofluorescence was performed on the paraffin-embedded sections. Unmasking of the antigen retrieval was performed by the heat-mediated antigen retrieval method in 0.01 M citric acid (pH 6.0). The Zytochem Plus Detection kit (ZytoMed, Germany) was used for development as described by the manufacturer [16]. In brief, 5-µm paraffin sections were deparaffinized at 60°C, immersed in xylene, and hydrated in a graded series of ethanol aqueous solutions. Antigen retrieval was performed using a citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0) and heating the sample for 10 min with an 800-W microwave. Washes were performed with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) following each step of the protocol. The sections then were immersed in freshly prepared 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min in the dark to block endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were immersed in Avidin/Biotin complex solution for 15 min at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with a blocking serum supplied by ZytoMed (Plus HRP kit, Broad Spectrum kit; Berlin, Germany) for 5 min to block non-specific staining. Antibodies against TLR 2, 3, 4, and 7 were diluted at a ratio of 1 : 200 in 0.01 mol/l PBS (pH 7.4) and finally incubated at 4°C overnight. The aforementioned sections were then washed three times for 5 min with PBS. A diluted (1 : 200) specific secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (TRITC) was incubated for 60 min at room temperature. Sections were washed three times for 5 min with PBS. DAPI counterstaining was used to stain the nuclei. Aqueous medium was used for the coverslip. The staining and immunohistochemistry sections were examined microscopically with a Leica DMLS2 light microscope (Leica Microsystems Wetzlar GmbH, Germany) by two experienced pathologists who were blind to the groups.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Liver tissue specimens were rinsed with sterile (DEPC-treated) water, immediately placed in DNA/RNA-free vials with RNAprotect Tissue Reagent (Qiagen, USA), and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis of mRNA levels of TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, IRAK4, TIRAP, NF-kB, and MYD88 molecules. Total RNA was isolated using the Trizol system (Gibco-BRL). 1 µg of total RNA was then transformed into complementary DNA (cDNA) with Superscript II RNase H-reverse transcriptase (Gibco Life Technologies) and oligo (dT) primer. The primers of all TLR-1, -2, -6, MYD88, TIRAP, IRAK4, and NF-kB proteins used were designed for the animal model. DNA was amplified using the Primus 96plus PCR machine (MWC-Biotech, Munich, Germany). Briefly, each 20-µl reaction contained 2 µl of cDNA (20 ng of total RNA), with each primer at a concentration of 200 nM, and 10 µl of Kapa Sybr Fast qPCR master mix (KAPA BIO, Boston MA, USA). After an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, the PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C × 30 s, 60°C × 40 s, 72°C × 40 s, 40 cycles. All samples were repeated in duplicate, and the mean cycle threshold (Ct) value for each sample was used for data analysis. The 2-ΔΔCT method of analysis of relative gene expression using qRT-PCR was used to calculate the relative changes in gene expression. All data were normalized to GAPDH levels and expressed as percentages (%) relative to controls, as previously described [17].

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was the expression of TLRs in subjects undergoing partial hepatectomy or not. Alterations in liver function tests were considered secondary endpoints of the study.

Statistical analysis

Correlations between groups were analyzed by ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey tests for each clinical entity. Continuous variables in groups before and after the intervention were compared with the paired t-test. The regularity of the distribution was estimated with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Pearson correlation and multiple regression analysis were used to investigate possible associations between hemodynamic and pathologic parameters after the interventions. All calculations were performed using GraphPad version 5 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The significance level chosen was p < 0.05.

Results

Primary outcomes qRT-PCR analysis

TLRs and their connecting molecules were measured among the different experimental groups. The qRT-PCR tests indicated significant differences in the levels of all molecules measured (TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, IRAK4, TIRAP, NF-kB, MYD88) between all LR and Sh groups at specific time points following partial hepatectomy (LR12 vs. Sh12, LR24 vs. Sh24, LR36 vs. Sh36, LR168 vs. Sh16). In addition, a progressive increase in the expression of TLRs was observed in the first three pairs, whereas their expression was constant in the last group. MYD88 expression showed no significant difference between groups LR168 and Sh168. Moreover, the qRT-PCR tests indicated no significant differences in immune response protein expression between groups LR12 and LR24. In contrast, significant differences were observed in the expression of TLR2, MYD88, IRAK4, TIRAP, and NF-kB between groups LR24 and LR36. Finally, there was a significant difference in the expression of TLR2, MYD88, IRAK4, TIRAP, and NF-kB between groups LR36 and LR168 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) between the groups at the same time point is indicated as follows: (A) Sh vs. LR, (B) 12LR vs. 24LR, (C) 24LR vs. 36LR, (D) 36LR vs. 168LR, (E) 12LR vs. 36LR, (F) 12LR vs. 168LR, (G) 24LR vs. 168LR. At each time point (12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 168 h), the Sh (n = 10) and LR (n = 10) groups were compared in terms of PCR expression

TLR – Toll-like receptor, MYD88 – myeloid differentiation protein 88, IRAK – interleukin-1 receptor-associated-kinase, TIRAP – Toll/IL-1 receptor adapter protein, NFkB – nuclear factor kappa-lightchain-enhancer of activated B cells.

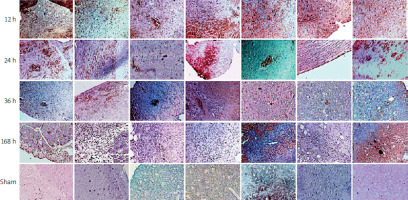

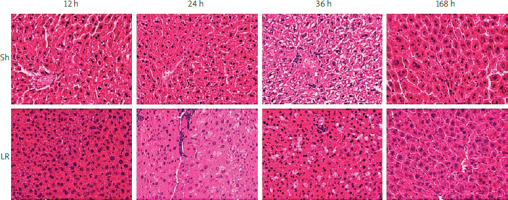

Histopathological analysis: immunochemistry

Histological examination of liver specimens using H&E staining revealed regeneration of liver tissue in the LR groups (Figure 2). Moreover, hepatic fat accumulation was evident 24 h after hepatectomy, which was 12 h before the hepatocytes entered the first cycle of proliferation. In addition, fat droplets were prominent 36 h after hepatectomy, throughout the first wave of hepatocyte proliferation. Obviously, hepatocyte proliferation and hepatic fat accumulation were coupled during liver regeneration. No inflammatory reaction or fat accumulation was observed in the control (Sh) groups.

Figure 2

Histopathological analysis of liver tissue specimens with hematoxylin and eosin staining

Sh – sample hepatectomy group, LR – liver resection group.

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed increased expression of immune response proteins (TLR1, TLR2, MYD88, IRAK4, TIRAP, NF-kB), indicating hepatocyte activation during liver regeneration in the LR groups as compared to the control groups (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining of the liver specimens, which were collected at specific time points after partial hepatectomy, indicated dynamic changes in the distribution of proteins in the liver and their localization within the hepatocytes. Twelve hours after partial hepatectomy, the expression of all measured proteins was found at specific parts of the hepatocytes. TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 were detected in the cell membrane, and the remaining proteins were found in the cytoplasm and nuclei of the hepatocytes. Twenty-four hours after partial hepatectomy, when the first peak of hepatocyte mitosis occurred, TLR1, TLR2, MYD88, IRAK4, TIRAP, and NF-kB were found to be expressed in the hepatocyte nuclei, indicating high transcriptional protein activity. Thirty-six hours after partial hepatectomy, when the second peak of hepatocyte proliferation occurred, TLR1, TLR2, MYD88, IRAK4, TIRAP, and NF-kB were only detected in the cytoplasm and the nuclei of the positive stained cells. At 168 h following partial hepatectomy, when the third wave of hepatocyte division peaked, elevated protein expression was observed in certain regions of the regenerative liver segments, which was localized at the cytoplasm and the nuclei of the hepatocytes.

Remarkably, in the great majority of mitotic hepatocytes, there was no protein expression at 36 h and 168 h, as compared to 12 h and 24 h after partial hepatectomy.

Secondary outcomes

Blood count tests (WBC and RBC), as well as liver function tests (SGOT, SGPT, T-BIL, D-BIL, ALP, and γ-GT) were significantly different between LR and Sh groups that were sacrificed at the same time point after surgery (LR12 vs. Sh12, LR24 vs. Sh24, LR36 vs. Sh36, LR168 vs. Sh168) (Figure 4, p < 0.05). A progressive deterioration of liver function was observed 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h after sacrifice for both groups (LR and Sh), whereas an improvement of liver function was noted 168 h after sacrifice for both groups. In addition, there were significant differences between groups LR24 and LR36 in WBC, RBC, SGPT, TBIL, DBIL, ALP, and γ-GT levels, whereas there was no significant difference in SGOT levels (p < 0.05). Finally, significant differences were observed between groups LR36 and LR168 in all blood count tests and liver function outcomes (p < 0.05).

Figure 4

Blood and biochemical analysis: (A) white blood cells (WBC); (B) red blood cells (RBC); (C) serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT); (D) serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT); (E) g-glutamyl transferase (GGT); (F) total bilirubin. Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Statistical significance is considered as p < 0.05; aSh vs. LR, bLR12 vs. LR24, cLR24 vs. LR36, and dLR36 vs. LR168 at each time point (12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 168 h), Sh (n = 10) and LR (n = 10). White bars – sham groups; black bars – LR groups (G) direct bilirubin; (H) alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Statistical significance is considered as p < 0.05; aSh vs. LR, bLR12 vs. LR24, cLR24 vs. LR36, and dLR36 vs. LR168 at each time point (12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 168 h), Sh (n = 10) and LR (n = 10). White bars – sham groups; black bars – LR groups

Discussion

Liver regeneration is a complex process that is based on an immune response reaction involving several molecules. The present study focused on the interaction between TLRs (TLR1, TLR2, TLR6) and their connecting molecules (IRAK4, TIRAP, and NF-kB) after 2/3 partial hepatectomy in a mouse model. The expression of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 showed significant differences between the LR and Sh groups at specific time points after the partial hepatectomy. The expression of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 in the LR groups was significantly higher throughout the liver regeneration process compared to the Sh groups. In addition, a greater difference in TLR levels was observed between LR and Sh groups at 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h compared to that at 168 h after partial hepatectomy. This finding is likely the result of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 expression often being reduced as the liver regeneration process reaches completion after 7 days (168 h). Similar outcomes were observed for MYD88 expression between the LR and Sh groups at specific time points after partial hepatectomy. Finally, laboratory tests (SGOT, SGPT, TBIL, DBIL, γ-GT) and full blood count (RBC and WBC) analyses indicated that there was a deterioration at the beginning of liver regeneration, which tended to stabilize after 168 h.

IRAK4, TIRAP, and NF-kB levels showed significant differences between LR and Sh groups at specific time points following partial hepatectomy. Although TLR levels tended to normalize near 168 h after hepatectomy, when liver regeneration was almost completed, the expression of IRAK4, TIRAP, and NF-kB continuously increased at this time point. The innate immune reaction, which characterizes liver regeneration, seemed to continue even after liver mass restoration at 7 days after hepatectomy. The changes of intra- and intercellular junctions that indicate late reorganization of liver architecture 168 h after hepatectomy seemed to be affected by the innate immune reaction of liver regeneration, as TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, MYD88, IRAK4, TIRAP, and NF-kB mRNA level analyses demonstrated an interaction between these molecules [18]. However, as the interaction between the expression of these molecules did not present a clear trend, further conclusions could not be drawn.

Many studies have been carried out on the role of TLRs in liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in experimental models, but the question remains debated. Seki et al., in their study on the contribution of Toll-like receptor/myeloid differentiation factor 88 signaling to murine liver regeneration, found that in MYD88-depleted mice after partial hepatectomy, the expression of immediate early genes involved in hepatocyte replication was subnormal, which was associated with impaired liver regeneration [16]. TLR2, 4, and 9 did not seem to be essential for NF-κB activation and IL-6 production after partial hepatectomy, which was thought to exclude a possible contribution of TLR2/TLR4 or TLR9 to MYD88-mediated pathways. However, they concluded that the TLR/MYD88 pathway is essential for incidental liver restoration, particularly its early phase. A study by Campbell et al. on proinflammatory cytokine production in liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice had a very similar conclusion [17]. In MYD88 knockout (KO) mice after partial hepatectomy, expression of genes related to the acute phase of liver regeneration (TNF, STAT-3, Socs3, Cd14) and circulating molecules (IL-6, serum amyloid A2) levels were significantly lower or blocked compared to heterozygous and wild-type mice. In contrast, TLR4, TLR2, and Cd14 KO mice did not show IL-6 deficits or any delay in hepatocyte replication. Therefore, they concluded that TLR4, TLR2, and CD14 do not contribute to regulating cytokine production or DNA replication after partial hepatectomy. MYD88-dependent pathways appear again to be responsible for TNF, IL-6, and their downstream signaling pathways. On the other hand, a recent study from Zhang et al. concluded that TLR5 plays an essential role in acute liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy [19]. They revealed that TLR5 activation contributes to the initial events of liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Their study findings demonstrate that TLR5 signaling regulates liver regeneration positively and suggest the potential role of TLR5 agonist to promote liver regeneration.

Lipid accumulation after PH is a consequence of enhanced fatty acid mobilization, increased hepatic lipogenesis and decreased secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein. It is suggested that hepatic lipid accumulation is required from the increased energy needs for cell proliferation during LR. However, the role of hepatic steatosis during liver regeneration is debatable. Some studies show that hepatic steatosis may be crucial for liver regeneration, while others show that altered hepatic lipid metabolism and accumulation did not interrupt the hepatic regenerative response. The biological significance of PH-induced lipid accumulation is still unclear [20].

The expression of TLRs in mice liver has been investigated in a variety of experimental studies, including septic models. However, a different pattern of TLR expression has been observed in these models. In Aravanis et al.’s study, the expression of TLRs at the beginning of sepsis was low but increased as sepsis became more severe, and animal mortality was secondary to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and septic shock, indicating the role of TLRs in liver function deterioration secondary to an extreme immune response due to sepsis [14]. In our study, TLR expression was high at the beginning of the regenerative process, and tended to decrease and normalize upon completion of liver regeneration.

Animal models provide a better understanding of the mechanisms that occur during liver regeneration, which are difficult to observe in clinical trials. There are several models for liver regeneration, such as surgical, pharmacological, and pre-existing trauma models. Partial hepatectomy could be better standardized and presents great importance from a surgical point of view. Animal choice is also important, and mice seem to be a great option [21]. Partial hepatectomy in mice is widely utilized because of its characteristics: simplicity, reproducibility, and strong similarity to human liver regeneration. The exact mechanisms of liver regeneration are complex and have not yet been completely clarified. The involvement of TLRs in this process might be secondary to both tissue damage and microbial presence. Partial hepatectomy, as a model of studying liver regeneration, introduces three insults that seem to involve TLRs in this process: trauma due to laparotomy and hepatectomy, necrosis secondary to ligation of liver tissue, and microbial contamination of liver due to disruption of the liver–intestinal barrier and portal vein infiltration by gut flora [22]. Acute liver failure, cirrhosis, steatosis, and cholestasis are common complications after hepatectomy, and TLRs are involved in all of these procedures, but their exact role remains unclear [23].

Although partial hepatectomy in mice is a well-established experimental model to study liver regeneration, the small size of the animals and their regenerative rhythm do not correspond closely to humans; therefore, the study results could not be directly extrapolated to humans. The time of liver harvesting after 2/3 partial hepatectomy is extremely crucial for the expression of TLRs, as the primary phase of liver regeneration occurs at the first 4 h when there is rapid expression of genes that stimulate cell proliferation [24]. The second phase of regeneration begins just after the primary phase, and hepatocyte proliferation peaks at 36 h after partial hepatectomy, after which the regeneration rhythm begins dropping [9, 25]. In our experimental protocol, 95% of liver regeneration was accomplished within 7 days (168 h). Therefore, the liver specimens were harvested at 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 168 h after hepatectomy. Euthanasia of animals and harvesting of liver 4 h after hepatectomy (i.e., during the primary phase of regeneration) may be crucial, and could help the investigation of TLR expression during the primary phase of liver regeneration.

Many studies have shown that TLR2 activation can evoke pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses that are highly dependent on the cell type and the cell compartment in which it is expressed, the ligand, and the co-receptors. While the well-known heterodimerization of TLR2 with TLR1 or TLR6 leads to the classical pro-inflammatory response in different cell types, the anti-inflammatory reaction serving as an immune regulator seems to be more heterogeneous. TLR agonists and/or inhibitors could be used in further research projects that could assist in assessment of pro- or anti-inflammatory action of TLRs in LR [26].

The present experimental study highlighted the role of TLRs in liver regeneration, as well as the function of their connecting molecules during this process. Several analyses were performed, including histopathologic assessment, blood tests, and qRT-PCR. In addition, the experimental protocol was predefined, which enhances the reproducibility of the present study. However, the experimental groups were small, no therapeutic intervention was applied, and no TLR agonists or inhibitors were used. Therefore, future studies should be designed focusing on the impact of different interventions on several pathophysiologic routes of liver regeneration.

The present study aimed to investigate the participation of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 in liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Liver regeneration is a complex process, which is accomplished by a cascade of mediating factors that play specific roles, which could not be easily estimated. However, it has been suggested that an uncomplicated liver regeneration could be achieved in some types of TLR- and MYD88-deficient mice. Therefore, the expression of TLRs and their possible role in avoiding complicated liver regenerative procedures should be further investigated [27, 28]. Understanding the role of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 might contribute to a potential target to regulate liver regeneration using inhibitors or accelerators after hepatectomy. Inhibition of TLRs as a treatment option for inflammatory diseases has already been widely investigated [29]. This approach could be useful in avoiding complications (e.g., steatosis, cirrhosis, and acute liver failure) following hepatectomy. In addition, the liver regenerative process could be enhanced to achieve better clinical outcomes after hepatectomy. Quantification of TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 expression during liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy appears to be essential to observe, identify, and understand the role of TLRs during this process.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated the role of TLRs in liver regeneration after 2/3 partial hepatectomy in a mouse model. At the beginning of the liver regeneration process, the expression levels of TLRs were significantly higher in the LR groups compared to the control groups at the same time points. At the end of liver regeneration, the expression of these receptors was higher in the LR group than in the Sh group but tended to be stabilized compared to the three first LR groups. This result is possibly explained by the progressive adaptation of liver function as liver regeneration tends to be accomplished. It seems highly possible that TLRs play a role in liver regeneration and could represent an effective therapeutic target in the management of acute or chronic liver failure after partial hepatectomy. In any case, further research should be conducted to understand their exact role and reveal further potential therapeutic targets.