The article reports a case of a patient with jaundice caused by multiple aneurysms of the visceral arteries (VAAs) complicated by aneurysm rupture located in the common hepatic artery network. Aneurysms of the visceral arteries are a rare pathology. They progress asymptomatically until their rupture and cause intraabdominal bleeding [1–3]. The most common location of visceral aneurysms is the splenic artery (about 60–80% of cases), while the visceral trunk and mesenteric arteries are less commonly involved [1]. Most visceral aneurysms (about 80%) are up to 20 mm in diameter. Visceral aneurysms of 50 mm in diameter and more meet the criteria for giant aneurysms [4]. It is estimated that only about 20% of giant aneurysms are symptomatic, and about 20% ultimately rupture, causing hemorrhage into the peritoneal cavity and/or gastrointestinal tract [4].

A 56-year-old man was admitted to the Department of Digestive Diseases with symptoms persisting for 2 weeks, such as jaundice, abdominal pain radiating to the lower back, temperature of 38°C, weight loss of approximately 7 kg, and loss of appetite. Moreover, the patient reported epigastric and right upper abdominal quadrant pain and nausea. Physical examination revealed hypotension with blood pressure 96/58 mmHg and tachycardia 105/min.

Blood laboratory testing performed at admission revealed signs of anemia and cholestasis: hemoglobin concentration of 7.7 g/dl, aspartate transaminase (AST) of 142 U/l (normal ≤ 40 U/l), alanine transaminase (ALT) of 188 U/l (normal ≤ 40 U/l); total bilirubin level was 6.94 mg/dl (normal range: 0.3–1.2 mg/dl) and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) was 595 U/l normal ≤ 55 U/l. Moreover, increased inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (96.3 mg/dl, normal ≤ 5 mg/dl) were reported. Viral hepatitis A, B, and C was excluded. Lipase and amylase levels at admission were within normal limits.

Abdominal ultrasound revealed enlargement of the widened biliary ducts of the left lobe of the liver and distended gallbladder (106 mm length in diameter) with thickened walls without gallstones. Furthermore, fluid collections adjacent to the pancreatic head were described. Suspicion of pancreatitis complicated with acute peripancreatic fluid collections was raised. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed the presence of multiple aneurysms of the splenic, common and right hepatic arteries (VAAs). The largest one was located in the common hepatic artery: 80 × 75 × 80 mm in size, which displaced the pancreatic head downwards, causing enlargement of the gallbladder and jaundice. Moreover, edema of the pancreatic head was described in CT imaging.

In the splenic artery, 3 aneurysms were detected (50 × 44 × 52 mm, 23 × 19 mm, and 18 × 12 mm). Moreover, the presence of layers of concentrated fluid, probably blood, around the liver, spleen and gastric fundus was visualized (Figures 1 A–C). Therefore, the patient was immediately transferred to the Department of Vascular Surgery and underwent implantation of a balloon-expandable stent graft into the common hepatic artery (8 × 57 mm, Bentley). The positive effect of the procedure was confirmed in a follow-up angio-CT scan performed on postoperative day 7 (Figures 2 A–C). Moreover, complete normalization of bilirubin, AST, and ALT levels was observed after 7 days. At the follow-up visit 30 days after the last hospitalization, follow-up tests, including complete blood count, CRP, AST, ALT, and total bilirubin, had normalized. The patient’s further clinical course is unknown, as he did not attend subsequent follow-up visits.

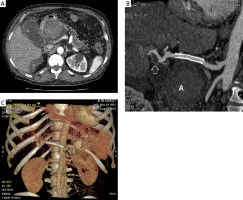

Figure 1

A – Computed tomography (CT) image of the abdominal arterial phase (acquisition about 20 s after intravenous administration of a contrast agent at the level of the epigastrium) – a small aneurysm with a parietal thrombus located in the distal part of the hepatic artery is visible (black arrow). Superficially located distended gallbladder (G). Lateral to the midline, a large aneurysm with an irregular parietal thrombus located along the course of the splenic artery (white arrow) is visible. B – CT image of the abdominal arterial phase (acquisition about 20 s after intravenous injection of a contrast agent at the level of the epigastrium 6 cm below) showing a large aneurysm, 80 mm in diameter, with irregular parietal thrombus and obliterated external contours, located along the course of the common hepatic artery (white arrow). Lateral visible gallbladder (G). Surrounding the liver, fluid is visible (B). C – CT image of the arterial phase – 3D reconstruction shows a prominent small aneurysm with parietal thrombus located in the distal part of the hepatic artery (white arrow). A large ruptured aneurysm along the course of the common hepatic artery (red arrow). Along the course of the tortuous splenic artery, 3 aneurysms are located (black arrows)

Figure 2

A – CT image after the applied treatment (angiographic phase, acquisition about 20 s after intravenous injection of contrast agent, intra-abdominal region) showing a large aneurysm, located along the course of the common hepatic artery, with no streaking of contrast into the sac (white arrow). The gallbladder is visible laterally (G). There is persistent fluid around the liver (B). B – CT image after treatment (angiographic phase, curved reconstruction along the common hepatic artery and hepatic artery) showing the implanted stent graft and the aneurysm located along the course of the common hepatic artery without contrast streaking into the pouch (A). Distally from the stent graft, an aneurysm with a small wall defect is visible along the course of the hepatic artery (white arrow). C – Arterial phase CT image – 3D reconstruction shows implanted stent graft (white arrow), aneurysm along the course of the common hepatic artery without contrast streaking into the sac (A). Along the course of the tortuous splenic artery, 2 aneurysms are visible (black arrows)

Aneurysms of the visceral arteries complicated by rupture are most often pseudoaneurysms that result from complications of the inflammatory process, neoplasms, type B aortic dissection extending into the coeliac axis, and iatrogenic trauma after surgery such as pancreaticoduodenectomy or partial hepatectomy [5–7]. Primary VAAs represent a rare finding with an incidence ranging between 0.1% and 0.2% [4]. Etiological factors include atherosclerosis and congenital disorders. While rupture of a pseudoaneurysm is usually associated with pancreatitis, trauma, or complications after surgery, rupture of a primary aneurysm can occur suddenly in a young, healthy subject [3, 5, 7].

VAAs may cause abdominal pain, hemorrhagic events, and mechanical jaundice resulting from external compression of the biliary ducts [1, 3, 4].

The patient presented here was burdened with five aneurysms in the visceral trunk vicinity, including two that met the criteria for giant aneurysms (dimension greater than 50 mm) [4]. Secondly, symptoms associated with aneurysm rupture were unobtrusive, suggested bile duct disease, and progressed very slowly, at least for 2 weeks.

Finally, it is noteworthy that multiple and large aneurysms significantly limited the possibility for surgical treatment. Splenic artery embolization, most commonly practiced especially in the splenic artery basin, often leads to vessel occlusion, which in the case of the common hepatic artery could result in liver ischemia [7–9]. Flow-directing stents, which are increasingly widely used in this type of lesion, may have been insufficient due to active bleeding from the aneurysm [8].

Stent graft implantation has proven to be a safe and effective solution. This solution is increasingly widely used outside the aorta, but in the visceral trunk vicinity it is often difficult to apply due to the tortuous nature of the vessels [5]. By maintaining vascular patency in the visceral trunk axis, the possibility of treating lesions along the course of the splenic artery in the next stage remained open.