INTRODUCTION

Each year in Europe about 1,200 children and adolescents aged from 10 to 19 take their own lives; more than twice as many boys (69%) do this as girls (31%) [1]. Ukraine is one of the European countries with the highest suicide rate among adolescents aged 15-19. In 2019, the rate in Ukraine for this age group was 9.4 per 100,000 of the population (3.6 for girls and 14.9 for boys). In Poland, the rates were much lower, with 5.3 for the entire youth group, 2.6 for girls, and 7.8 for boys [2].

Suicidal behaviours include not only suicides but also suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. In addition to suicidal behavior, non-suicidal self-injury is a serious related problem in adolescence. The primary differentiating factor is intention. Non-suicidal self-injury is defined as direct and deliberate self-harm enacted without a desire to die. A history of non-suicidal self-injury is a strong risk factor for adolescent suicidal behavior [3].

According to some models of suicidal behaviours, thoughts of taking one’s own life initiate the suicidal process, and through plans and attempts lead to suicide [4]. It is estimated that 15-year-olds with suicidal ideation are 12 times more likely to attempt suicide before the age of 30 [5]. In addition, one-third of young people with suicidal thoughts develop a suicide plan, and approximately 60% of adolescents with a plan go on to attempt suicide. Most plans and attempts are made within the first year of the onset of suicidal thoughts [6].

Analysis of the personal experiences of suicidal adolescents shows that they have not only thought about suicide but also manifested these thoughts and intentions quite vividly and publicly [7]. Often a teenager’s suicide attempt is intended to alert those around him/her that something bad is happening to them, that he/she needs help [8]. Therefore, it is important to catch thoughts at an early stage to prevent the actual suicide. Since the role of suicidal thoughts in triggering suicidal behaviour is vital, it is crucial to determine the prevalence of suicidal thoughts among young people as well as to identify the factors that increase or decrease the risk of their having thoughts about suicide.

Prevalence of suicidal thoughts

The percentage of adolescents who report having had suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months ranges from 14% to 18% [9, 10]. The most recent data provided by the Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (YRBS) [11] showed a significant increase in the prevalence of girls seriously considering attempting suicide, from 24.1% in 2019 to 30% in 2021. For boys, the rates were similar (2019: 13.3%, 2021: 14.3%).

Social, religious and cultural factors influence adolescent suicidal behavior. In some traditional cultures, external factors such as loss of prestige and position in society, and experiencing abuse or discrimination play a greater role. In other cultures, adolescent suicide attempts and suicides may be driven by an internal sense of hopelessness or worthlessness. Values and messages that vary across religious systems also play an important role in adolescent suicidal behavior [12].

A large-scale research study of a representative sample of Polish adolescents aged 12-17 indicates that 5.7% manifested suicidal tendencies, during their life the highest prevalence (8.5%) reported by 16-17-year-olds [13]. A study of Ukrainian adolescents aged 12-18 conducted in Odessa found that almost 6% reported suicide attempts, and nearly a third reported thoughts of death and planning suicide [14]. However, it is important to remember that prevalence rates of adolescent suicidal behavior generated from surveys that were not fully anonymous may produce underestimations due to the stigma and guilt associated with this issue.

The COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the mental health of many young people around the world [15]. The data of the Polish Police Headquarters covering the years of the pandemic indicated upward trends in both the number of suicide attempts and suicides among adolescents up to the age of 18 [16]. According to the State Statistics Service of Ukraine, there was no significant increase in the number of teenage suicides during the pandemic [17].

It must be remembered that the number of suicide attempts by children and teenagers recorded by official statistics represents only a small proportion of those actually undertaken by teenagers. Their actual number is difficult to estimate. It is safe to assume that many suicide attempts are not disclosed to the police or health care systems by young people or their families.

Risk and protective factors

A strong predictor of a young person having suicidal thoughts is depression [8, 18]. The odds of suicidal thoughts are almost 5 times higher in adolescents reporting symptoms of depression. Suicidal behaviours are significantly more frequently recorded in girls with depression (33.3% at ages 12-14 and 69.1% at ages 15-17) compared to boys (19.2% and 27.7%) [19]. Another group of individual risk factors is anger, aggressive behaviour, alcohol consumption and drug use [20].

Among relational risk factors, peer violence plays a large role. According to a study of adolescents from 10 European countries, those who were victims of verbal, relational, and physical bullying were more likely to engage in suicidal behaviour. Physical victimization was associated with a 39 percent increase in the risk of suicidal ideation and relational victimization with a 28 percent increase in the likelihood of a suicide attempt [20]. Risk factors related to the school environment include being bullied, being offered illegal drugs on school premises, and perceived safety concerns regarding the school environment [21].

One of the factors that protects adolescents from suicidal behaviour is religiosity [22]. Findings also suggest that family support and parental monitoring play an important role. Good communication between parents and children reduces the likelihood of suicidal thoughts in all age groups of children [23].

The study aimed to assess the prevalence of suicidal thoughts among 14-15-year-olds in Lviv and Warsaw and to identify in both populations the psychosocial factors that increase or decrease the frequency of them. The study was part of a larger Polish-Ukrainian survey conducted in the Lviv region and Warsaw to analyse adolescents’ substance use, mental health problems, problematic Internet use, and antisocial behaviour [24-27].

METHODS

Participants and procedure

A questionnaire survey was conducted parallel in two urban centres of Lviv (Ukraine) and Warsaw (Poland) among adolescents at the same time (November-December 2020) and in the same manner and methodology. The research tool was an anonymous online questionnaire filled out by students at secondary school classes randomly selected for the study. The methodology of the survey was based on the Mokotów Study that has been conducted in Warsaw since the early 1980s and in Lviv since 2016. The primary purpose of the Mokotów study is to observe trends in the use of psychoactive substances by school students, as well as to observe changes in mental health problems (e.g. symptoms of depression). Antisocial behavior, cyberbullying and problematic Internet use are also being monitored.

The Mokotów study uses a relatively short questionnaire, which is filled out by randomly chosen students in the first grade of secondary schools (Warsaw) and ninth grade in Ukraine. Consistent use of the same survey questions ensures to a large extent the comparability of the results of individual rounds of surveys and allows for systematic monitoring over the long term of changes in the use of psychoactive substances, other risky behaviors and mental health problems of school students [25, 28].

Sample

In both locations, the survey included students aged 14-15 who attended different types of secondary schools. The unit of randomization was the school classroom. In Lviv, 28 classes from 27 schools were randomly selected; in Warsaw, 36 classes from public schools and 12 classes from non-public schools were drawn from the three districts of Mokotów, Ursynów, and Wilanów. Finally, the analysis included 1085 students from Lviv (57% female) and 794 students from Warsaw (52% female). The mean age of respondents in Lviv was 14.3 years (SD = 0.48), while in Warsaw it was 14.7 years (SD = 0.66). The differences between the average age in the two locations proved to be statistically significant (t(1338.6) = –15.869; p < 0.001). In both locations, the majority of survey participants (72% in Lviv and 77% in Warsaw) had at least one parent with a university degree. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the two samples.

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics of the samples from Lviv (Ukraine) and Warsaw (Poland)

Procedure

In Warsaw, after obtaining permission from principals a letter of similar content was forwarded through the school to the parents of students, along with a form requesting parental consent. In Lviv, information about the survey was posted in parents’ groups (on Viber and Messenger) along with a parental consent form. The procedure of so-called passive consent was used, but in several schools, at the request of the school administration, the procedure of active parental consent was applied. To comply with the legislation in force in Ukraine, the questionnaire was checked by specialists from the Cabinet of Psychology and Social Work of the Lviv Regional Institute of Postgraduate Pedagogical Training. In Poland, the Bioethics Committee of the Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology in Warsaw approved the survey procedure. The survey was administered in classrooms by remote data collectors from outside the school, using an online questionnaire that students filled out on their smartphones or tablets. The response rate in Lviv was 86%, and in Warsaw it was just under 70%. The difference in response rate in the two locations was due to the greater number of refusals on the part of Warsaw school principals and parents.

Measures

Frequency of suicidal thoughts in the last 12 months was measured by a single question as the dependent variable. Though the frequency of suicidal thoughts was measured by a single question (with a 4-point Likert response scale), the theoretical validity of this question is satisfactory. This is evidenced by a moderately high positive correlation with the scale of symptoms of depression; rho-Spearman = 0.491 (in Lviv) and 0.497 (in Warsaw). The other correlations of this single question with risk and protective factors are in line with theoretical assumptions about their direction and strength (see Table 5).

Table 2

Descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables across locations

| Variables (number of items) | Lviv (Ukraine) | Warsaw (Poland) | Sample item (type of scale used) | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | α | M (SD) | α | |||

| Dependent variable | ||||||

| Suicidal thoughts (1) | 1.26 (0.68) | NA | 1.40 (0.78) | NA | Have you ever, in the last 12 months, had suicidal thoughts come to mind?; 4-pt Likert: 1 = ‘did not happen’, 4 = ‘yes, often’ | OSDUS[29] |

| Independent variables | ||||||

| Risk factors: Mental health issues | ||||||

| Symptoms of depression (4) | 1.88 (0.77) | 0.87 | 2.11 (0.88) | 0.91 | In the last 7 days how often have you felt sad? 4-pt Likert: 1 = ‘never or rarely’, 4 = ‘all the time’ | CES-D [30] |

| Lack of energy (1) | 2.39 (1.35) | NA | 2.93 (1.43) | NA | Have you felt a lack of energy in the past month? 5-pt Likert: 1 = ‘did not feel’, 5 = ‘yes, more than a dozen times’ | HBSC [31] |

| Consultation with a school or mental health specialist (1) | 1.3 (0.68) | NA | 1.27 (0.73) | NA | In the past 12 months, have you contacted a doctor, nurse, school pedagogue, or psychologist because of emotional or mental problems? 4-pt Likert: 1 = ‘I have not been in contact even once’, 4 = ‘I have regular contacts’ | Research team |

| Difficulties with coping during the COVID-19 pandemic (4) | 2.28 (0.70) | 0.63 | 2.62 (0.81) | 0.76 | To what extent was the pandemic period (Spring 2020) difficult for you personally? 5-pt Likert: 1 = ‘not at all’, 5 = ‘to a very large degree’ | Research team |

| Risk factors: Safety issues | ||||||

| Feeling unsafe at school (1) | 1.88 (0.84) | NA | 1.71 (0.62) | NA | Do you agree with the statement: I feel safe at my school? 4-pt Likert: 1 = ‘definitely yes’, 4 = ‘definitely no’ | Research team |

| Online victimization (1) | 1.13 (0.45) | NA | 1.30 (0.70) | NA | Have you ever been in this situation: one or more people from your school, class, or online community, for an extended period regularly bullied you using/via the Internet or a cell phone in such a way that you suffered and found it difficult to defend yourself? 4-pt Likert: 1 = ‘did not happen’, 4 = ‘it happened 4 times or more’ | [32] |

| Risk factor: Risk behaviours | ||||||

| Alcohol use and drunkenness (2) | 1.32 (0.66) | rho = 0.43 | 1.20 (0.55) | rho = 0.50 | How many times (if at all) in the last 30 days have you had any alcoholic beverage (e.g. beer, wine, vodka, cognac, whiskey)? 7-point Likert: 1 = ‘I did not drink’, 7 = ‘20 times or more’ | [33] |

| Company of peers who use drugs (1) | 1.06 (0.40) | NA | 1.49 (1.01) | NA | In the last year, did you happen to be in a youth company where narcotics were used? 5-pt Likert: 1 = ‘did not happen’, 5 = ‘more than a dozen times’ | [34] |

| Protective factors | ||||||

| Family Relationships (12) | 3.03 (65) | 0.90 | 2.87 (0.60) | 0.87 | In our family, we really help and support each other) 4-pt Likert: 1 = ‘definitely no’, 4 = ‘definitely yes’ | [35] |

| Religiosity (2) | 2.6 (0.89) | r = 0.60 | 2.14 (0.99) | r = 0.69 | How often do you go to church? 4-pt Likert: 1 = ‘never’, 4 = ‘once a week or more often’ | [36] |

Table 3

Prevalence of suicidal thoughts in the last year among adolescents in Lviv (Ukraine) and Warsaw (Poland) across gender

Table 4

Comparison of risk and protective factors in the two study locations (Lviv and Warsaw)

Table 5

rho-Spearman correlations among study variables for adolescents from Warsaw (Poland) (above the diagonal) and adolescents from Lviv (Ukraine) (below the diagonal)

The independent variables consisted of three groups of psychosocial risk factors: mental health issues (symptoms of depression, consultation with a school or mental health specialist, lack of energy, difficulties with coping during the COVID-19 pandemic), safety issues (feeling unsafe at school, online victimization), risky behaviours (alcohol use and drunkenness, company of peers who use drugs), and two protective factors (good family relationships, religiosity). Symptoms of depression were measured with the shortened Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [30]. This scale consists of four questions about the frequency of sadness, loneliness, moodiness, and crying in the last 7 days. Selection of these independent variables was based on a large body of previous research assessing factors related to adolescent suicidal behaviors [8, 20, 22]. Table 2 presents the dependent and independent variables along with the number of items in each measure, means and standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas if appropriate, a sample item from each measure, and the source of the measure.

Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic variables included gender, parental education, and family structure. Gender became dummy-coded to 1 = males and 2 = females. Family structure responses were: ‘with parents’, ‘only with father’, ‘only with mother’, ‘with one of the parents’, ‘with stepmother/stepfather’, and ‘with another person’. Based on these responses, a dichotomous variable was constructed where 1 = ‘those who lived with both parents’ and 2 = ‘those who did not’. Possible answers for maternal and paternal level of education ranged from 1 = ‘completed elementary school/primary’ to 4 = ‘completed college or university/higher’. The highest reported education level of either the mother or the father was used in the analyses. Parental education was not included in the regression analysis because of missing data that exceeded 20-30%.

Data analysis

The distributions of the dependent variable were right-handedly asymmetric and differed significantly from normal distributions. All measures which significantly correlated with the dependent variable were used in multiple regression analyses. In the next step, we applied generalised linear models (GENLIN) with gamma distribution. After controlling for two sociodemographic variables (gender and family composition) a selection procedure based on Wald’s statistics was used (similar to the stepwise selection procedure in multiple linear regression) to find the best model predicting suicidal thoughts among young people. The risk of collinearity was tested before the regression analyses. The results of correlation analyses between independent variables were used for this purpose (see Table 5). None of the correlations exceeded 0.6, which could expose the regression analyses to the negative consequences of collinearity. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics v. 29.0.2.0 statistics packages.

RESULTS

Descriptive analyses

The detailed frequency of suicidal thoughts by gender and study location is shown in Table 3. Significantly more adolescents in Warsaw (25.0%) had suicidal thoughts at least once or twice in the past year than those in Lviv (16.3%). In both locations, suicidal thoughts were significantly more prevalent among girls than boys: 22.4% vs. 8.3% in Lviv and 34.1% vs. 15.1% in Warsaw. Girls in Warsaw as well as in Lviv were more likely to have suicidal thoughts (at least once or twice, sometimes, or often) than boys. Most teenagers had suicidal thoughts once or twice in the last year; however, about 3.5% of the study participants in both locations were at high risk of suicidal behaviour due to frequent suicidal ideation. In both locations, adolescents living with both parents had a lower prevalence of suicidal thoughts (14.2% in Lviv and 23.9% in Warsaw) than adolescents living in single-parent or stepparent families (26.8% in Lviv and 29.9% in Warsaw). These data are not shown in Table 3.

Table 4 shows a comparison of risk and protective factors in the two study locations. Five (of eight) risk factors for suicidal thoughts had higher rates among study participants in Warsaw. These included the following: Company of peers who use drugs, Online victimization, Lack of energy, Symptoms of depression, and Difficulties with coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only for two risk factors (Feeling unsafe at school, Alcohol use and drunkenness), were higher rates observed among students in Lviv. For one risk factor there was no significant difference (Consultation with a school or mental health specialist). Our comparisons clearly indicate that the rates of two protective factors (Religiosity and Family Relationships) were significantly higher among the Lviv students. The correlation results for all study variables were all in the expected direction, though small or moderate (correlations are shown in Table 5).

Regression analyses

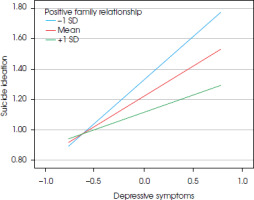

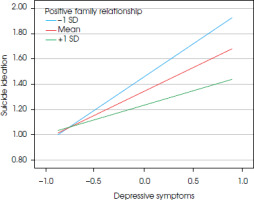

The results of regression analyses are presented in Table 6. Our results indicated that the risk factors representing mental health problems (lack of energy, symptoms of depression, and emotional or mental health problems that prompted consultation with a specialist), online victimisation, and company of youth who use drugs were associated with increased frequency of suicidal thoughts in both locations. Two other variables (alcohol use/abuse and feeling unsafe at school) appeared to be significant risk factors for suicidal thoughts in Lviv, but not in Warsaw. Difficulties with coping during the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to be insignificant in both locations. Positive family relationships reduced the frequency of suicidal thoughts in both cities, but religiosity was a significant protective factor in Lviv only. Our regression model also included a risk/protective interaction (Family relationship × Symptoms of depression). Our results indicated that positive family relationship buffers the negative impact of symptoms of depression on the frequency of suicidal thoughts in both locations. Figure I and II depicts the interaction effects for Lviv and Warsaw separately. The graphs illustrate the relationship between a risk factor (symptoms of depression) and frequency of suicidal thoughts for the low (one standard deviation below the mean), medium (the mean), and high levels of positive family relationship (one standard deviation above the mean). These results indicate that the relationship between symptoms of depression and frequency of suicidal thoughts is weakest among adolescents who reported the highest levels of positive family relationship.

Table 6

GENLIN regression predicting adolescent frequency of suicidal thoughts from sociodemographic, risk, and protective factors in two locations: Lviv (Ukraine) and Warsaw (Poland)

Figure I

Relationship between symptoms of depression and the participant’s suicidal thoughts among Lviv study participants for low, medium and high levels of positive family relationship – low: −1 SD (standard deviation), medium: mean, high: +1 SD

Figure II

Relationship between symptoms of depression and participant’s suicidal thoughts among Warsaw study participants for low, medium and high levels of positive family relationship – low: −1 SD (standard deviation), medium: mean, high: +1 SD

Our regression model explaining the frequency of suicidal thoughts in adolescents turned out to fit the data quite well both in the group of Lviv students (Omnibus test = 834.88; df 12; p < 0.001) and the Warsaw group (Omnibus test = 510.22; df 12; p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

In Lviv, about 16% of the study participants reported having suicidal thoughts at least once in the past year, which corresponds well with the other results around the world [9, 10]. In Warsaw, the rates were significantly higher. The slightly younger age of the Ukrainian adolescents and degree of exposure to risk factors can be considered here. The adolescents in Warsaw were more exposed to risk factors specifically related to suicidal thoughts including online victimization, lack of energy, symptoms of depression, and were less exposed to protective factors (good family relationships/religiosity) than adolescents in Lviv. This combination of risk and protective factors could have made the Warsaw adolescents more prone to suicidal thoughts.

Our study confirmed that suicidal thoughts are more prevalent in adolescent girls, which is consistent with previous studies [11, 20]. This is likely related to the greater susceptibility of female adolescents to exposure to stress, symptoms of depressed mood, and depression [37].

As expected, symptoms of depression were found to be the strongest risk factor among all of the adolescents in the survey. The greater the severity of the symptoms of depression, the more frequent were the suicidal thoughts among adolescents in both countries. These findings are in line with previous studies [6, 38] and theoretical assumptions regarding suicidal behaviors [3]. Depressive mood associated with a pessimistic view and hopelessness is strongly associated with suicidal ideation [39].

Lack of energy and mental health problems that require a visit to a specialist were also associated with a higher frequency of suicidal thoughts. Fatigue is often a symptom of a variety of emotional and mental health problems. If these problems are so disorganising of daily life that they require a visit to a specialist this may be another risk factor for suicidal thoughts.

Contrary to our expectations, we found no association between difficulties with coping during the COVID-19 pandemic and the frequency of suicidal thoughts among the study participants in both Lviv and Warsaw. However, this does not mean that the pandemic itself was not a significant risk factor, as it likely had delayed negative effects on adolescent mental health that had not yet occurred at the time our study was conducted. Reports from the literature suggest that the challenges of the pandemic may have contributed to increased mental health problems among adolescents, including higher levels of suicidal thoughts [15].

In both Lviv and Warsaw a higher frequency of being a victim of online bullying was found to be associated with a higher frequency of adolescent suicidal thoughts. Similar results came from a Canadian study, which indicated that involvement in cyberbullying as a victim contributed to the prediction of symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation [40]. Our results show that, in Lviv, students’ sense of insecurity at school was associated with the frequency of suicidal thoughts. The lower the feeling of safety at school, the higher the frequency of suicidal thoughts. In Warsaw, this factor was found to be insignificant. Students in Lviv had lessons in schools with short periods of online learning, while students in Warsaw had online lessons only and were locked in their homes for several months. Therefore, they were less affected by the feeling of being unsafe at school during this time.

Our analysis revealed that, both in Lviv and in Warsaw, a higher frequency of suicidal thoughts was associated with the frequency of being in the company of peers in situations in which drugs were used. This result is consistent with previous research on factors for suicidal behaviour [19]. However, the frequency of a combined measure of alcohol use and drunkenness was significantly associated with the frequency of suicidal thoughts among adolescents in Lviv only. The latter had a relatively higher level of alcohol consumption than their peers in Warsaw, which is likely related to much looser pandemic restrictions in Lviv and opportunities to gather with peers.

We found that good relations within the family were associated with a lower frequency of suicidal ideation in both samples. This result confirms the high importance of good family relationships for a child’s healthy development and resilience [41]. Furthermore, good relationships with family were found to moderate the association between symptoms of depression and suicidal thoughts. Adolescents who struggled with the former but maintained good relationships with their parents had a lower frequency of suicidal thoughts. This result supports once again the role of family-based intervention in preventing mental health problems during adolescence. Family support and good relationships are perhaps the best-known factors influencing young people’s resilience [42].

Previous studies indicate that religiosity has a significant negative association with suicidal thoughts in young people [22]. Our results showed that in Lviv religiosity among adolescents was a significant protective factor against the frequency of suicidal ideation. In Warsaw, as already noted, this factor was found to be insignificant. Although Poles generally have a high level of religiosity, Ukraine, especially the Western regions like Lviv, shows greater religious heterogeneity with higher religiosity levels. This interesting difference in results calls for further research on differences in religiosity among Polish and Ukrainian teenagers.

Religiosity in the context of suicidal behavior can be an ambiguous factor. In religious systems, suicide is often condemned and seen as a weakness of spirit, a grave sin or a violation of God’s laws, so it can be stigmatized, making it difficult to seek help for a mental health problem. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors can lead a religious individual to isolation, self-stigmatization and increased feelings of guilt. On the other hand, religiosity can act as a source of support, helping individuals find a deeper meaning to life and the strength to overcome a crisis. In this sense, it can be treated as a protective factor.

Most of the psychosocial factors found to be important among adolescents were the same in students in Lviv and Warsaw. Some differences in factors (religiosity, alcohol use, and abuse) do not change the picture of great similarity. This confirms the general impression of cultural closeness between the Polish and Ukrainian societies, which has been strengthened recently due to the crisis of the war and the wave of immigration of Ukrainian neighbours to Poland. Our findings indicate that the similarity extends to the determinants of mental health problems and suicidal behaviour among adolescents.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has several important limitations. First, the main limitation is the use of a single-item measure, as it may not fully capture the complexity of suicidal thoughts, coping mechanisms and the broader spectrum of suicidal behavior. Our measure does not distinguish between passive and active suicidal thoughts, or the severity or persistence of these thoughts. It does not ask about suicide plans or attempts to assess suicidal tendencies in adolescents. Examining the frequency of suicidal thoughts is useful for a general assessment of the problem, but insufficient for assessing the current risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents. Despite these limitations, single-item measurements remain a valuable tool in population-based studies of adolescents, providing significant insight into their mental health problems.

Another major limitation of the study is the failure to include several key factors such as traumatic events, domestic violence, non-suicidal self-injury and sexual abuse, although we used measures of several important psychosocial factors like symptoms of depression, cyberbullying, and risk behaviours. Our survey was conducted in two countries, which provides a more extensive picture of the psychological functioning of young people. However, due to the cultural closeness of Poland and Ukraine, it may be impossible to extrapolate the results to other sociocultural contexts.

An important limitation of our study is its cross- sectional design and the use of a questionnaire as the only source of information on suicidal thoughts, psychosocial risk and protective factors. A good solution to this problem would be to verify students’ responses on the basis of other sources, for example those of parents or teachers. Such methods are used in studies on children and young people with mental health problems [43]. However, this solution is expensive and raises other difficulties related to discrepancies in data taken from several sources.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our research conducted simultaneously among students in Warsaw (Poland) and Lviv (Ukraine) indicate that an effective reduction of the frequency of suicidal thoughts in adolescents can be based on three types of preventive measures. The first is early detection and treatment of adolescent depressive disorders and other mental health problems. In this context, helping the family maintain good relationships with their teenage children is an essential part of prevention efforts. Supportive family relationships are key factors in adolescent resilience. The second promising direction is to counter cyberbullying, combined with increasing the sense of security at school. The third direction is the prevention of risky behaviour in adolescents and, above all, the reduction of the use of psychoactive substances among them.