Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the formation of erosions and ulcerations of the colonic mucosa. The diagnosis of UC is based on the clinical presentation, endoscopic evaluation, and histological examination. However, there are no pathognomonic features that determine the diagnosis. Therefore, a broad differential diagnosis is particularly important, while especially infection should be considered and excluded [1]. Sexually transmitted disorders (STDs) can be a mimic of UC, especially in patients who practice anal intercourse, and should always be considered in the course of diagnosis. Special diagnostic emphasis for STDs should be placed on patients who have receptive anal intercourse regardless of sexual orientation, but transmission of pathogens is also possible through fingering or oral–anal sexual contact or (in women) via genital infection due to the proximity of the vagina [2, 3].

Aim

The aim of the study was to show the situation of Polish patients in the context of differential diagnosis of UC with STDs.

Material and methods

The evaluation tool was a questionnaire on sexual habits, administered to patients with ulcerative colitis from two Polish centers for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), and to Internet users with the diagnosis of UC affiliated with patient portals. The survey was completely anonymous so that patient restraint could not affect the results.

Questions included sexual orientation, practicing passive anal sexual intercourse, unsafe sexual behavior, and differential diagnosis with STDs at the time of diagnosis or in exacerbation of UC (Table I). MS Excel was used for statistical analysis.

Table I

Questions included in the survey

Results

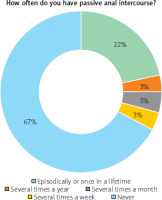

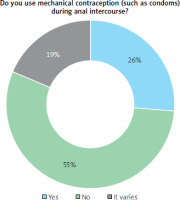

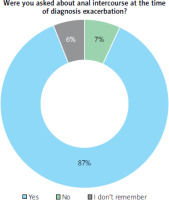

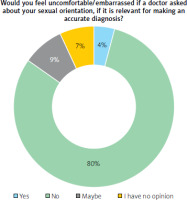

The survey included 532 participants (characteristics of the patients are shown in Table II). Among the patients, 22.6% had extensive UC (Montreal E3), 35.3% had left-sided UC (E2), 14.3% had proctitis (E1), and 27.8% did not know the extent of the disease. Most of them (38.3%) were diagnosed with UC more than 5 years ago. The distribution of sexual orientations among respondents was as follows: 53.4% heterosexual women, 34.2% heterosexual men, 4.1% men who have sex with men (MSM), 3.4% bisexual women, 1.9% women who have sex with women (WSW), 1.5% bisexual men, and 1.5% chose a different answer. 31.6% of all respondents reported engaging in passive anal sex: 70.2% episodically or once in a lifetime, 10.7% several times a year, 14.3% several times a month, and 4.8% several times a week (Figure 1). When asked about unsafe sexual behavior, 7.6% of patients answered affirmatively; among MSM the percentage rises to 73%. Furthermore, 55.4% of anal intercourse takes place without mechanical contraception (Figure 2). During medical visits related to the diagnosis or exacerbation of UC, the vast majority (87.2%) of patients were not asked about either anal sexual intercourse or sexual orientation (Figure 3), and 76.7% were definitely not tested for STDs. However, the results indicate that MSM are more frequently tested for STDs than the general population (27% vs. 13.5%). At the same time, 80.5% of respondents say they would not feel uncomfortable with questions like these (Figure 4), and 12.8% of them had a history of diagnosis of one or more STDs in the past. The association of anal sexual intercourse with the extent of the disease on the Montreal scale was also analyzed, showing no such relationship.

Table II

Characteristics of patients

Discussion

STDs affect the colon or the rectum, causing symptoms such as rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and urgency of stool [4]. Similar symptoms are associated with IBD. Because of that, the diagnosis of STDs may be delayed due to their resemblance to IBD, especially if the physician will not consider such a diagnosis without having information that the patient is in a risk group. Levy et al. described a cohort of 16 patients who were misdiagnosed with IBD. Diagnosis of STDs was delayed by up to 36 months, and the most common misdiagnosis was actually chlamydiosis [5]. How many similar cases do we not know about?

The most common STDs in the colon include Chlamydia trachomatis (mainly lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV)), gonorrhea, syphilis, human papilloma virus (HPV), herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [6]. Among our patients, chlamydia was the most commonly diagnosed infection (20 patients), followed by syphilis (4 patients), gonorrhea (10 patients), and HIV (2 patients). Additionally, 32 patients reported other unspecified STDs. Although the endoscopic and histopathological pattern of IBD and STDs is very similar, Arnold et al. described several features suggestive of STDs on histopathological examination, such as minimal active chronic crypt centric damage, a lack of mucosal eosinophilia, submucosal plasma cells, endothelial swelling, and perivascular plasma cells [7]. This may be helpful, but a definitive diagnosis can only be made after targeted investigations; for example, rectal swabs for Gram stain, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests and culture should be collected. In 2021 the European Guideline on the management of proctitis, proctocolitis and enteritis caused by sexually transmissible pathogens was published [4]. It provides insights into diagnosing and treating STDs. In the literature, the most commonly reported diagnostic mistakes of STDs and IBD involve the MSM population (with a prevalence between 11 and 84% [5, 8–11]. Soni et al. reported that none of their patients with IBD were tested by a gastroenterologist for STDs. This was only done in a clinic dedicated to the diagnosis of venereal diseases [9]. Andrews was a physician working simultaneously in inflammatory bowel disease and genitourinary clinics [10]. This allowed him to demonstrate the scale of the issue even more effectively. The aforementioned case reports show that gastroenterologists often do not consider STDs in the differential diagnosis of IBD. According to current guidelines, first-line treatment for ulcerative colitis involves the use of mesalazine. However, it is often necessary to promptly initiate corticosteroid therapy or immunosuppressive treatment soon after diagnosis [12, 13]. Consequently, patients suffering from STDs are improperly treated with steroids and mesalazine when they actually require antibiotic therapy. In 2004, the Health Protection Agency (HPA) in the UK introduced a national surveillance program to help control the spread of STDs. Every patient with symptoms of proctitis was tested for chlamydiosis. Consequently, 849 cases of LGV were diagnosed between 2003 and 2008, the majority of whom had symptoms of proctitis. They were primarily MSM and patients co-infected with HIV [14]. Our study indicates that MSM more frequently engage in unprotected intercourse and are more often tested for STDs. It does not mean that MSM constitute the only group that should be tested. Anal sexual behaviors are widely practiced in the heterosexual population. It is more common than having a Twitter account in the United States [15]. In reference to Habel's et al. study, approximately one third of heterosexual women and men had ever engaged in anal sex. Importantly, less than one third of them use condoms [16, 17]. However, cases of STDs in the colon within the heterosexual population are less frequently described in the literature. In 1988, Rigoriadis and Rennie described 2 cases of heterosexual women presenting with Chlamydia trachomatis infection in the left side of the colon and rectum [18]. It has also not been demonstrated in our study that sexual orientation or anal intercourse influences the extent of the confirmed UC (particularly its occurrence in the rectum). This is more significant in the context of STDs and may vary depending on the disease entity. In the study by Soni et al., STDs most commonly caused proctitis. However, involvement of the sigmoid colon was also observed [9]. Cologne and Hsieh suggested that ulcerations and inflammation are limited only to the distal 10 cm in LGV proctitis [19]. In contrast, Ijiri et al. described a case of syphilis involving both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract, with lesions affecting the stomach, ileum, and descending colon [20]. Therefore, STDs should not be overlooked by gastroenterologists, even when lesions do not involve the rectum.

Conclusions

We believe that diagnostic mistakes between UC and STDs may be more common than appears, and this results from neglecting questions about sexual health during the medical history taking. Consequently, patients with symptoms of colitis are not frequently tested for STDs, while histopathological examination of colon biopsies may not provide a definitive answer. In our study, 87.2% of patients were not asked about either anal sexual intercourse or sexual orientation. At the same time, 80.5% of respondents say they would not feel uncomfortable with questions like these. Therefore, it must be concluded that the issue does not lie with the patients, who may not always be aware of what can impact the diagnosis, but rather with the physicians, who, despite their knowledge, are embarrassed to ask questions. We are confident that bringing this issue to the attention of our fellow clinicians will contribute to more thorough diagnostics and a reduced number of misdiagnoses.