INTRODUCTION

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by significant problems with attention, impulsiveness and excessive activity which is higher when compared with the sufferer’s peers. The term “attention deficit disorder” was introduced in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in the 1980s, and in DSM-IV (1994) the term was further renamed into “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” [1]. According to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11), ADHD is defined as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a persistent pattern (lasting at least 6 months) of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that directly and negatively impacts academic, occupational, or social functioning. The symptoms must be evident prior to age 12, typically by early to mid-childhood, although some individuals may not be identified until later [2]. Approximately 7-10% of school-age children suffer from ADHD, making it one of the most common behavioural problems in childhood [3]. Worldwide, approximately 2-5% of adults experience ADHD symptoms [4, 5]. In India, the pooled prevalence of ADHD among children and adolescents is 7.1% [6]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional surveys from 1980 to 2023 among the South Asian countries, Pakistan has the highest prevalence of the disorder, while Bangladesh exhibits the lowest [7]. In a meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents in Africa was 7.47% [8]. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 study estimated an age-standardized global prevalence of ADHD at 1.13% across the lifespan, with over 84 million people affected in 2019 [9]. The prevalence of ADHD in different populations is given in Table 1 [10-14]. Over the past 20-to-25 years, there has been a noticeable rise in the prevalence of ADHD. Some studies have suggested that negative symptoms of childhood ADHD persist into adulthood, destroying quality of life, increasing the risk for obesity, the earlier use of tobacco and drugs, an earlier initiation of sexual activity, and many other morbidity and mortality health indicators, including even premature death by external and accidental causes [15, 16]. Studies have shown that the male central dopamine system matures more slowly than the female. Hence, this delay increases the chance of alterations in central dopamine system, which could help partly explain the higher prevalence of boys with ADHD than girls [15, 17].

Table 1

Prevalence of ADHD in different populations

| Population group | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Children (global) | 7-10 |

| Adults (global) | 2-5 |

| All ages (GBD 2019) | 1.13 |

| In children | |

| North America | 11.3 |

| Latin America | 10.0-20.4 |

| Europe | 2.0-5.0 |

| Asia | 4.2-6.5 |

| Africa | 1.3-22.2 |

Three types of ADHD have been recognized: 1) the combined type, 2) the inattentive type, and 3) the predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type. The latter is the most prominent among school-age children, followed by the combined subtype and the predominately hyperactive type [18].

In the US alone, the annual cost of ADHD to society is $14,500 per child ($42.5 billion overall), including sums for schooling, crime, unemployment, and the use of healthcare and medications [19]. Also, a meta-analysis that examined the prevalence of ADHD in incarcerated populations provided evidence for high rates of undiagnosed ADHD among individuals with a history of criminal behavior and antisocial outcomes, which emphasizes the need for a comprehensive analysis of this disorder at all levels [20].

AETIOLOGY AND GENETICS OF ADHD

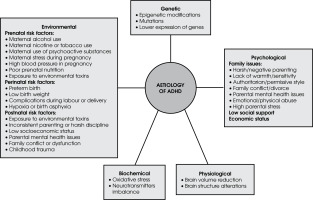

It is challenging to determine the exact cause and pathophysiology of ADHD due to the complex interplay and variability of contributing factors, which include genetic, neurobiological, and environmental influences that are often overlapping and interdependent. Contributory factors include those which are genetic, psychological, biochemical, physiological, and environmental (Figure I). A widely accepted theory about the aetiology of ADHD is the “dopamine hypothesis”, which links it to an impairment of the dopaminergic system. Patients have higher levels of dopamine transporter (DAT) binding and less access to dopamine receptor isoforms. ADHD is also linked with a generalised malfunction of the noradrenergic system [21].

The genetic makeup of ADHD is still unknown, despite its high heritability rate of 70-80%. A genetic linkage study was the first genome-wide approach used to identify the specific DNA sequence that is transmitted in ADHD within families. A meta-analysis identified strong genome-wide linkage at chromosome 16 between 64 and 83 Mb, and nine other areas (bins 5.3, 6.3, 6.4, 7.3, 8.1, 9.4, 15.1, 16.3, and 17.1) have a nominal linkage signal, indicating that they might include genes associated with ADHD [22]. The disorder has a polygenic aetiology because several candidate genes, including those involved in dopamine, noradrenaline, and serotonin transmission and metabolism, contribute to making complex traits. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as well as variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs), are the markers used to study the polymorphisms in candidate genes associated with childhood ADHD [21]. The most promising candidate genes significantly associated with ADHD include dopamine transporter gene 1 (DAT1), dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4), dopamine D5 receptor gene (DRD5), serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT), serotonin 1B receptor (HTR1B), and synaptosomal-associated protein 25 gene (SNAP25) [23].

Studies have shown that along with the dopaminergic neurotransmitter system, genes involved in the neuro-transmitter systems such as the adrenergic system, serotonergic system, cholinergic system and nervous system development pathway also act as a significant candidate genes (Table 2) [24].

Table 2

Major candidate genes studied in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Epigenetics and ADHD

Epigenetics is the study of the inheritance of chromatin modifications in the absence of DNA sequence alterations. In mammals, the most common epigenetic modification is methylation (addition of methyl groups ([CH3]) of cytosine, followed by adenine and guanine methylation [25, 26].

The most extensively researched and well-understood epigenetic marker for ADHD at present is DNA methylation (DNAm). The main candidate genes for DNAm epigenetic studies include those from the dopaminergic, serotonergic, and neurotrophic systems such as serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4), DRD4, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR). DNAm in peripheral blood and saliva has been the subject of several investigations regarding its correlation with ADHD diagnosis [27]. In a study that investigated the association between DNAm and ADHD symptoms from birth to school age, it was confirmed that the emergence of ADHD symptoms later in life was linked to DNAm at birth [28]. Similarly, the first methylome-wide clinical investigation revealed that methylation of the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 2 (VIPR2) gene is linked to ADHD symptoms [29]. The findings indicated that children with ADHD had less methylation of this gene compared to controls.

In a study examining DNAm profiles at birth, cord blood was used, which was collected immediately after delivery, before any effects from the environment might have taken hold [30]. In this study lower DNAm levels in the selected regions in DRD4 and 5-HTT genes were associated with higher ADHD symptom scores. Another study indicated that epigenetic regulation of the DRD4 gene in the form of increased methylation is associated with cognitive/attention deficits in ADHD [31].

Many pieces of research have shown that exposure to several environmental factors, including perinatal stress, the social environment, medications, toxins, and early trauma, can affect epigenetic processes. In one study it was discovered that lead exposure increases epigenetic modification (histone acetylation) in rats [32]. Several studies showed that VIRP2 methylation and ADHD risk factors such as pre-pregnancy weight gain, prenatal tobacco smoking and early malnutrition are highly correlated [33-35].

Age-related methylation patterns have enabled the development of “epigenetic clocks,” which estimate biological age (EpiAge) based on specific DNAm sites correlated with chronological age. By comparing EpiAge to chronological age, researchers can assess biological aging through the residuals – commonly referred to as epigenetic age acceleration, or the “EpiAge Gap.” Epigenetic aging has been increasingly linked to mental health outcomes in populations of developing children, adolescents and young adults, particularly in the context of internalizing and externalizing disorders. Recent research specifically examines the relationship between epigenetic aging and ADHD in children and adolescents [36]. Understanding the epigenetic mechanisms underlying ADHD and the impact of environmental factors on the disorder could lead to the development of novel medications and interventions.

ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS ON ADHD

The brain of an infant is relatively undeveloped at birth, and the first year of life is a time of substantial brain growth and development, including the establishment or loss of cellular connections and cell culling. ADHD, like most psychiatric disorders, is influenced by interactions between genotype and environmental factors. However, it is still unclear how environmental factors or genotype-by-environment interactions may affect ADHD. Both internal and external environmental factors can dynamically and occasionally reversibly alter the epigenome. Studies on DNAm profiles at birth and child ADHD symptoms revealed that exposure to adverse environmental factors during the prenatal or perinatal period increases the risk of ADHD [30].

Chemicals and ADHD

The World Health Organization’s “State of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals” report demonstrated that the increase in neurodevelopmental disorders can be due to exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) [37]. Phthalate mixture, bisphenol A, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and pesticides are other chemicals associated with ADHD symptoms [17, 38-42]. Several studies focused on the relationship between prenatal and postnatal exposure to persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and ADHD [43].

Diet and ADHD

The nutritional factors that contribute to the development of ADHD include a lack of certain minerals (such as iron, copper, magnesium and zinc) and malnutrition [44]. Hence, reducing the symptoms of ADHD may be accomplished by changes in diet and nutrition. The most promising dietary therapies appear to be elimination diets and fish oil supplements [45]. One study found that the increase in the use of yellow artificial food colour resulted in behavioural symptoms in ADHD children. In this study, an analysis of tartrazine (FD&C yellow #5, E102), a lemon-yellow synthetic food colorant, in commercial orange beverages was performed [46]. Tartrazine ingestion leads to decreased zinc levels in serum and saliva, increased zinc loss through urine, and worsened behavioural and emotional responses in hyper-active children, with no such effects observed in control subjects. Higher copper concentrations lead to reduced dopamine levels [47]. Also, nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids like docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), amino acids like methionine and vitamin D deficiencies have significant effects on ADHD symptoms [48].

Perinatal or prenatal conditions and ADHD

ADHD risk is associated with perinatal and prenatal challenges such as maternal excess weight, low birth weight, hormonal contraception, mother’s age at pregnancy, maternal disease history, premature delivery, maternal psychopathology, and maternal smoking and alcohol consumption. The maternal immune response may cause an inflammatory response in the foetal brain, altering foetal brain development leading to the pathogenesis of ADHD [49]. Another study revealed that elevated titters of maternal thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPOAbs) in early pregnancy increased the risk of ADHD in children [50]. Maternal use of medicines like acetaminophen, antiasthmatic drugs, antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and valproic acid during pregnancy impairs foetal and infant neurobehavioral development [51, 52]. All types of maternal contraception, including oral and non-oral, combined and non-combined hormonal contraceptives, showed the same pattern of increased risk of ADHD in children [53, 54]. Exposure to infections and antibiotics throughout pregnancy and infancy is linked to a higher chance of developing ADHD [55].

Several studies have found an inconsistent correlation between maternal birth age and ADHD in children [56]. According to a systematic meta-analysis, there is a correlation between the risk of ADHD and younger parental age, while the age group of 31-to-35 has the lowest risk of ADHD [57]. The majority of the earlier studies have reported younger maternal age at birth as a risk factor for offspring ADHD, and some studies have shown that advanced parental age elevates the risk for offspring with ADHD [61]. The prevalence of ADHD is increased in cases of maternal obesity, excessive gestational weight gain (GWG), metabolic abnormalities in mothers (diabetes, hypertension, and pre-eclampsia), and unhealthy diets [62, 63].

The studies related to the association between maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and ADHD showed inconsistent results [64-66]. Meanwhile, there is a high correlation between paternal and maternal smoking with ADHD symptoms [67-70]. Similarly, it was reported that ADHD children showed an increase in delta power but a decrease in maturational power-to-power frequency-coupling between low frequencies and beta rhythms when compared to control subjects [71].

Low birth weight (LBW) and premature birth occur simultaneously in most cases, and both are stronger risk factors of ADHD. LBW has modest heritability, and it acts as an independent risk factor [72-75]. One study stated that prenatal ischemia-hypoxia (PIH) is a major cause of lower birth weight and increases the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD [76, 77]. Many studies demonstrated the association between ADHD and preterm birth [78, 79], which disrupts the regular development and organisation of neurons causing impairments in brain processes involved in response preparation, executive response control, and response inhibition, leading to ADHD symptoms [80].

Socio-economic position and ADHD

Many researchers noted the associations between socioeconomic position and risk of ADHD. Stressful contexts and adversities, including low income, discrimination, severe early childhood deprivation, substandard housing, crowded households, poor education and family turmoil make a crucial impact on the occurrence and later outcomes of ADHD [55, 81]. A systematic review emphasized that an average of 2.21 times greater likelihood of ADHD in a child from a low-socioeconomic status (SES) household than in those who came from high-SES families (125). The researchers also noted that parents’ educational qualifications and being a single parent are two major risk factors for ADHD, or increased symptoms of the condition.

The development of ADHD is influenced by a variety of parenting behaviours, including aggressive and angry parenting, limited parental involvement, poor coping skills, and nonauthoritative parenting approaches [82]. Children who witness early violence tend to exhibit nervousness, distraction, high levels of arousal, and impulsive aggression when faced with conflict [83]. It was revealed in one study that bullying emerged as a contributing factor to children’s ADHD symptoms [84]. Bullying behaviours in others or oneself are more common in children diagnosed with ADHD. The onset or exacerbation of symptoms of ADHD in these cases may be associated with feelings of insecurity and fear stemming from having been bullied. Higher exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) has been found in children with ADHD [85, 86]. Also, ACE scores were very high among recidivist violent offenders in India [87]. These studies suggest that ADHD, especially when combined with other risk factors such as Conduct Disorder, environmental influences, social difficulties, and lack of appropriate intervention, may lead to serious, violent and chronic (SVC) delinquency [87, 88]. Hence, effective management and early intervention for ADHD are crucial in mitigating these risks and preventing the escalation to serious, violent, and chronic delinquency. The key finding from various studies on the development of ADHD among the children within South Asian families pointed out the predominance of authoritarian parenting styles which exacerbate ADHD symptoms by placing excessive pressure on children or dismissing their struggles as behavioural issues [89]. This review urges that more research be conducted among South Asians in order to explore culturally specific parenting practices and their impact on ADHD outcomes.

THE NEUROBIOLOGY OF ADHD

Neurobiological studies have revealed that children with ADHD exhibit structural abnormalities in their brains. Significant alterations are found in the frontostriatal circuitry, areas of the cerebellum and temporoparietal lobes, and basal ganglia and corpus callosum [90, 91]. A meta-analysis indicated that the following brain regions exhibited the greatest volumetric reductions in ADHD compared to controls including the posterior inferior cerebellar vermis, the splenium of the corpus callosum, the right caudate, and the total and right cerebral volume [92]. Similarly, another study suggested that ADHD may be characterized by a delay in subcortical maturation [93], discovering asymmetric subcortical structure development as well as delayed volumes of subcortical structures in ADHD.

OXIDATIVE STRESS IN ADHD

The elevated oxidant levels and altered antioxidant system lead to progressive neuronal damage and deterioration of normal cerebral functions, which may induce the onset of ADHD [21, 94]. Dopamine becomes extremely prone to auto-oxidation when the antioxidant defence is weak, which can result in dopamine cytotoxicity and damage to the brain, particularly in the attention- and activity-related areas such as the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia [21].

MANAGEMENT OF ADHD

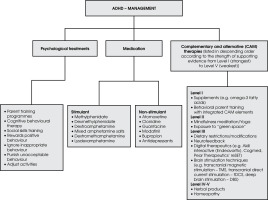

According to the studies, only 50% of individuals with ADHD exhibit clinical symptoms before the age of 7, in contrast to 95% who do so before the age of 12, and 99% before the age of 16 [95]. Parent training programmes (PTP) is the main intervention for ADHD in preschoolers; medication is not advised in these cases, according to NICE guidelines (2008). Psychological treatments, parent training programmes, group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), or social skills training are offered to school-age children with moderately severe symptoms of ADHD and moderate impairment. School-age children with severe impairment secondary to ADHD symptoms require medication. Rewarding positive behaviour, ignoring inappropriate behaviour, punishing unacceptable behaviour and adjusting activities to the child’s ability are the four simple, yet difficult-to-implement, principles used for the psychosocial management of ADHD [1]. Common stimulant drugs used in ADHD treatment include methyl phenidate, dexmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, mixed amphetamine salts, dextromethamphetamine and lysdexamphetamine. Non-stimulant medications are atomoxetine, α-2a adrenergic receptor agonists (clonidine and guanfacine), modafinil, bupropion and tricyclic anti-depressants.

Complementary and alternative (CAM) therapies are becoming increasingly widespread in the treatments for ADHD; these include homeopathy, dietary restriction and supplements, herbal products, biofeedback, and attention training. Several herbal therapies, including Pycnogenol (Pyc), St. John’s Wort and Gingko Biloba, are commonly used. Pyc is a French maritime pine bark extract, thought to function as a vasodilator, enhancing cerebral blood flow to brain areas and raising catecholamine levels in children with ADHD. Similarly, St. John’s Wort or Hypericum Perforatum is a natural supplement that blocks the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine [96]. It was found that the possible mode of action of St. John’s Wort may be comparable to that of two regularly prescribed drugs for ADHD, bupropion and ato moxetine [97]. Numerous pieces of research have revealed that the omega-3 fatty acid dietary supplement, which affects serotonergic and dopaminergic activity, is used to treat the symptoms of ADHD. The studies showed that the therapies include mineral supplements, sugar restriction, neurofeedback, cognitive training, mindfulness meditation, and exposure to “green space” which are also a part of CAM therapies for ADHD treatment (Figure II) [98]. More research investigations are needed in this area to establish the optimal benefits of CAM therapies. In India, the most populous nation, there is a need for more funding for ADHD research, an increase in the number of trained mental health professionals, the improvement of school-based support, and the creation of culturally adapted interventions [99].

CONCLUSIONS

ADHD remains a complex and multifaceted condition, and it has been suggested that there is more than one risk factor that contributes to ADHD in individuals, and that there are environmental and genetic components to ADHD, with moderate-to-high heritability. Unravelling the genetics of ADHD will be challenging and advances in genetic and neurobiological research have elucidated the intricate underpinnings of ADHD. Along with significantly more genetic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data, future research will likely provide more precise measurements of brain shape and function. The key component of managing ADHD is pharmacological therapy, especially stimulants which have shown significant success. However, a more comprehensive strategy that addresses individual requirements and minimises dependency on medicine is provided by the combination of behavioural therapies and revolutionary non-pharmacological interventions. A multidisciplinary framework, combining medical, psychological, and educational support, is essential for addressing the full spectrum of ADHD, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for those affected.