INTRODUCTION

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignancy worldwide, accounting for approximately 80% of nonmelanoma skin cancers [1]. BCC has the highest incidence in Australia (up to 1,000 cases per 100,000 annually), followed by the USA (212–407 per 100,000 annually for females and males, respectively) and Europe (76.21–157 per 100,000 annually, varying by country) [2]. BCC originates in the basal cells of the epidermis and is strongly linked to chronic ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure, which explains its predominance in sun-exposed areas like the head and neck, accounting for approximately 80% of cases [3–5]. Notably, not only cumulative sun exposure but also intense UV exposure during childhood has been implicated as a key risk factor contributing to the development of BCC in adulthood, underscoring the importance of early photoprotection [6]. The risk is further heightened by factors such as fair skin, immunosuppression, and genetic predispositions [7, 8]. Although BCC rarely metastasizes and is not typically life-threatening, its ability to invade local tissues, the high likelihood of recurrence, and its frequent occurrence in cosmetically and functionally sensitive areas necessitate careful management [10]. The impact on quality of life and the potential for significant morbidity underscore the importance of early detection and appropriate treatment. Diagnosis is primarily clinical, supported by dermoscopic examination, with biopsy performed to confirm the diagnosis in atypical cases or when histopathological evaluation is needed to identify the subtype [10, 11]. While smaller lesions with characteristic clinical and dermoscopic features may not require biopsy prior to treatment, it is essential for larger or ambiguous lesions to ensure accurate subtype determination.

Nodular BCC, which accounts for about 60% of cases, typically presents as pearly papules or nodules with telangiectasia and is often confined locally. Superficial BCC, making up 20% of cases, appears as flat, erythematous, scaly patches with well-defined edges and is more frequently seen on the trunk of younger patients. In contrast, morphoeic or infiltrative subtypes are characterized by scar-like plaques with indistinct borders, posing a higher risk of recurrence due to their aggressive and subclinical spread [12].

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines provide an essential framework for categorizing BCC into low-risk and high-risk groups based on recurrence potential, serving as a critical tool for guiding treatment strategies [8]. Low-risk BCCs are typically located in non-critical anatomical areas such as the trunk or extremities, display favourable histological subtypes like nodular or superficial patterns. High-risk BCCs, on the other hand, are larger, deeply invasive, recurrent, or associated with aggressive histological features such as infiltrative or basosquamous subtypes. These lesions are frequently located in high-risk areas, such as the central face (H-zone), periorbital region, ears, or other cosmetically and functionally sensitive regions, where achieving clear surgical margins is particularly challenging [8]. Additionally, tumours in immunosuppressed patients, lesions with aggressive features like perineural or perivascular involvement, and any BCCs treated with ablative procedures lacking histopathological control instead of surgical excision are also considered high risk [13]. A recurrence of invasive BCC in high-risk anatomical regions, such as the eyelids, nose, lips, or ears, poses a significant risk of functional and cosmetic complications, often requiring complex reconstructive interventions.

Thus, the management of BCC is tailored to the tumour’s type, size, location, histological features, and the patient’s overall health and preferences. Options range from surgical interventions to non-invasive therapies, with emerging systemic treatments available for advanced cases. Surgical excision remains the cornerstone of BCC management and offers the highest cure rates. While low-risk BCCs can often be treated with narrow excision margins, high-risk subtypes or lesions located in anatomically sensitive areas such as the central face or periorbital region may necessitate wider margins of up to 15 mm to minimize recurrence risk [6, 13, 14].

While radiotherapy achieves good control rates, potential long-term side effects – including chronic radiation dermatitis, hypopigmentation, and epidermal atrophy – may limit its use in younger patients. Furthermore, there is some concern regarding the potential for radiation-induced secondary tumours in the long term [2, 6].

Systemic therapies have become increasingly important for managing advanced or inoperable BCCs. The Hedgehog pathway is fundamental to the development of BCC, and inhibitors like vismodegib and sonidegib specifically target its molecular mechanisms, providing effective treatment options for locally advanced or metastatic cases.

Treatment strategies for BCC encompass a diverse range of options, including surgical, non-invasive, and systemic approaches. Surgical excision, particularly Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), continues to be the preferred choice for most cases due to its excellent cure rates and tissue-sparing benefits. Non-invasive therapies and radiation offer practical alternatives for selected patients, while systemic treatments are revolutionizing the management of advanced BCC.

In conclusion, BCC poses distinct challenges owing to its varied presentation, risk of recurrence, and frequent appearance in anatomically critical areas. Successful management depends on a thorough understanding of the tumour’s type, location, and associated risk factors, as outlined in evidence-based guidelines. While surgical excision remains a cornerstone of treatment, innovations in systemic therapies, diagnostic imaging, and reconstructive methods emphasize the importance of personalized approaches. Striking a balance between effective tumour control and preserving both functionality and aesthetics is vital for delivering optimal care to patients affected by this widespread form of skin cancer.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between the histological subtype of BCC and the radicality of surgical excision in the head and neck area among patients treated at the Department of Otolaryngology of a tertiary care hospital.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This was a retrospective, single-center, observational study analysing patients diagnosed with histopathologically confirmed BCC of the head and neck region.

The study included patients treated with surgical excision for skin tumors of the head and neck at the Department of Otolaryngology and Oncological Otolaryngology, in collaboration with the Clinical Department of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery, Military Institute of Medicine – National Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland, between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2022.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) surgical excision of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) located in the head and neck region, (2) histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis, and (3) availability of complete clinical and pathological documentation. Exclusion criteria comprised absence of histopathological confirmation, incomplete medical records, histological diagnoses other than BCC (e.g., melanoma), and cases managed without surgical intervention.

All lesions were evaluated clinically before excision. Dermoscopic examination was not routinely used in the preoperative assessment during the study period by doctors performing surgeries in our department, although some patients were referred from the Department of Dermatology where dermoscopic examinations were performed. The majority of tumours were excised using elliptical excision under local anaesthesia with standard safety margins based on clinical risk assessment: typically 3–5 mm for low risk lesions [6], and extended up to 10–15 mm for tumours in high-risk anatomical zones. The exact margin was determined intraoperatively based on clinical appearance and anatomical constraints. MMS was not available at our department and was not used. Histopathological analysis was performed to determine BCC subtype, assess excision margins, and evaluate for features such as ulceration, inflammation, elastosis, perineurial invasion, multifocality and presence of Demodex mites. Tumors were categorized as either primary or recurrent. Additionally, any history of previous dermatological or oncological surgery in the area of excision was recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistica 13.3 (StatSoft Poland, Dell Statistica Partner). Quantitative variables were summarized using descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation, median, and range). The normality of each variable was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Qualitative variables were summarized as percentages. To determine statistically significant differences among patients’ groups based on the radicality of surgical excision and type of BCC, occurrence of neuroinvasion and grading of elastosis, the χ2 test was applied. Additionally, to evaluate statistically significant difference in lateral and deep margins between groups, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used. The χ2 test was also used to assess correlations between ulceration and lesion visibility in macroscope image, the presence of other BCC lesions and subsequent procedures for the lesion, inflammation and grade of elastosis, presence of Demodex mites, radicality of surgical excision and specimen size. For differences related to the presence of Bowen’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in other locations, and depth of infiltration, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. A forward stepwise logistic regression analysis was conducted for the multivariate model. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Statistically significant differences were observed between the radicality of surgical excision and the occurrence of neuroinvasion. Neuroinvasion was more frequently found in patients who underwent partial excision (24.4% vs. 5.0%, table 1). Furthermore, a correlation between the type of BCC and the radicality of surgical excision was confirmed (p = 0.014); radical excision was most frequently performed in patients with superficial tumours (95.8%) and least frequently in those with micronodular tumours (62.5%, table 2). No statistically significant differences were noted between the radicality of surgical excision and the grade of elastosis.

Table 1

Correlation between tumour resection and neuroinvasion

| Tumour resection | Neuroinvasion | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| 0-R0 | 227 (95%) | 12 (5%) | < 0.001 |

| 1-R1 | 47 (74.6%) | 16 (25.4%) | |

Table 2

Correlation between tumour resection and type of BCC

No correlations were found between ulceration and BCC type (p = 0.089, table 3), inflammation and the presence of Demodex mites (p = 0.985, table 4), grade of elastosis (p = 0.063, table 5), previous lesion surgeries and the need for trimming (p = 0.398, table 6), or the presence of other BCC lesions (p = 0.598, table 7).

Table 3

Correlation between ulceration and BCC type

Table 4

Correlation between inflammation and the presence of Demodex mites

| Inflammation 0N, 1T non brisk, 2T brisk | Presence of Demodex mites | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| 0 | 135 (81.8%) | 30 (18.2%) | 0.985 |

| 1 | 67 (82.7%) | 14 (17.3%) | |

| 2 | 46 (82.1%) | 10 (17.9%) | |

Table 5

Correlation between inflammation and grade of elastosis

| Inflammation 0N, 1T non brisk, 2T brisk | Grade of elastosis | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 0 | 9 (5.4%) | 18 (10.9%) | 62 (37.6%) | 76 (46.1%) | 0.044 |

| 1 | 2 (2.5%) | 20 (24.7%) | 24 (29.6%) | 35 (43.2%) | 0.042 |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | 8 (14.3%) | 22 (39.3%) | 26 (46.4%) | 0.423 |

Table 6

Correlation between previous lesion surgeries and the need for trimming

| Previous BCC excision from this lesion site | Trimming | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| No | 259 (97%) | 8 (3%) | 0.398 |

| Yes | 33 (94.3%) | 2 (5.7%) | |

Table 7

Correlation between the presence of other BCC lesions and another surgery from this lesion

| Presence of other BCC lesions 0 – N, 1 – single, 2 – plural | Another surgery from this lesion | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| 0 | 130 (89%) | 16 (11%) | 0.439 |

| 1 | 52 (89.7%) | 6 (10.3%) | 0.830 |

| 2 | 91 (92.7%) | 7 (7.1%) | 0.315 |

Interestingly, in patients who underwent radical excision, the measured lateral and deep margins were statistically smaller than in non-radical cases. This finding likely reflects that non-radical resections were often performed on larger or more infiltrative tumors, where even wide surgical margins were insufficient to achieve clear histological boundaries, particularly at the deep margin.

The forward stepwise logistic regression analysis identified neuroinvasion as a significant variable associated with the radicality of surgical excision, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.15 (95% CI: 0.07–0.34) in the third step of the model.

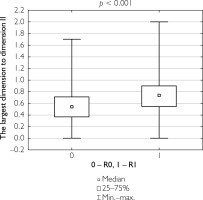

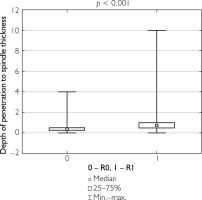

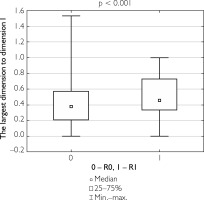

Additionally, correlations were evaluated between the ratio of the largest lesion dimension to the longitudinal and transverse dimensions of the specimen, as well as between tumor invasion depth and specimen thickness, in relation to the completeness of tumor resection. Patients who underwent complete tumor resection had a significantly lower ratio of lesion size to specimen dimensions and a lower tumor depth-to-specimen thickness ratio compared to those who underwent partial resection (table 8). Figures 1–3 illustrate these findings.

Table 8

Values of analyzed parameters presented as median and range

Figure 1

Box-and-whisker plot of the largest tumor dimension in patients undergoing total resection versus partial resection

DISCUSSION

Our findings correlate with those reported by Niculet et al., who observed perineural invasion (PNI) in 20.1% of cases and perineural chronic inflammation (PCI) in 30.2%, with the remainder showing neither PNI nor PCI. Their detection rate is markedly higher than the approximately 1% prevalence typically cited in the literature, underscoring that many factors – such as tumour size, location, and histological subtype – may influence PNI detection rates. Niculet et al. further noted that both PNI and PCI were seen more frequently in larger or more advanced tumours, which tend to invade deeper skin structures, including nerve fibres. Histological subtype also plays a critical role in the likelihood of PNI. While nodular BCC is one of the most common variants, it generally shows a lower incidence of perineural involvement. Conversely, superficial BCC usually demonstrates no PNI [15]. Massey et al. study provided evidence that PNI of unnamed nerves does not majorly affect BCC outcomes but is collinear with other high-risk features and therefore serves as an indicator of a more aggressive disease course [16].

Although we should not forget completely about neuroinvasion and the patient should be aware that even when primary tumour was excised with a proper surgical margin if neuroinvasion is present in pathology, it can even manifest clinically many years later, as illustrated by Ashraf et al., who reported cranial neuropathy due to perineural invasion 7.5 years post-Mohs surgery [17].

Our data highlight an ongoing challenge, as emphasized by Panizza and Warren, who noted that perineural invasion of head and neck skin cancers remains poorly understood and is often underdiagnosed [18]. Incidental or microscopic perineural invasion, identified by the pathologist, frequently raises uncertainty regarding subsequent patient management. In contrast, clinically apparent perineural spread, which presents with neurological deficits, may be misdiagnosed as other conditions, potentially delaying appropriate treatment.

We found that nodular BCCs were most frequently excised with clear margins (41.2%), whereas scleroderma-like tumours were the least likely to achieve complete excision (2.5%). This supports findings from previous studies, where aggressive subtypes like infiltrative and scleroderma-like BCCs demonstrated significantly lower excision rates compared to indolent subtypes like nodular and superficial BCCs. In a large cohort study by Poulsen et al., infiltrative tumours were shown to have a notably lower chance of complete excision, with odds ratios indicating the likelihood of radical excision for infiltrative tumours at only 48% of the rate for nodular subtypes [19].

The high recurrence rates associated with aggressive BCC subtypes are largely due to their deeper and more diffuse infiltration, which complicates clear margin achievement. Crowson’s classification of BCC as indolent (nodular, superficial) and aggressive (infiltrative, morpheaform, micronodular) supports this concept, emphasizing the need for wider surgical margins or alternative strategies like Mohs micrographic surgery. In our study, the infiltrative subtype strongly influenced the reduced success of radical excision, consistent with other research that links the presence of aggressive histological features to incomplete surgical removal [19–21].

The infiltrative subtype was also the most frequently associated with incomplete excision (30.1%) in studies by Sexton et al., reflecting the challenge of achieving complete resection without histological control [22]. This was further confirmed by the statistical analysis from Baltrušaitytė et al., which highlighted a high incidence of incomplete excision in patients with infiltrative BCC compared to nodular variants [23]. As previously noted by Aguayo-Leiva et al., ensuring complete excision for aggressive BCCs requires either larger surgical margins (5–10 mm) or the use of intraoperative frozen section analysis to guarantee negative margins.

Finally, while surgical margins of 5 mm have been deemed sufficient for smaller, non-aggressive BCCs, infiltrative BCCs and larger tumours demand careful planning with wider excision margins to reduce the risk of recurrence and ensure a successful long-term outcome [21, 24].

No statistically significant association was found between the grade of elastosis and the radicality of surgical excision in BCC cases. While elastosis is widely recognized as a histological marker of chronic UV radiation exposure, its direct impact on surgical outcomes remains unclear. Previous studies have reported conflicting results. Husein-ElAhmed et al. observed that moderate to severe elastosis (grades II–III) was significantly associated with incomplete excision, particularly in facial tumours. They proposed that dermal elastotic changes complicate the clinical delineation of tumour margins, thus increasing the likelihood of positive surgical margins [25]. In contrast, Drexler et al. found that while elastosis correlated more strongly with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), its relationship with BCC was weaker and varied by subtype. Although nodular and sclerodermiform BCCs tended to present with more elastosis than superficial types, this trend was not statistically significant, and the authors highlighted the need for larger sample sizes [26].

Historical data from Zaynoun et al. also emphasized the prevalence of elastosis in BCC (present in 93% of cases), particularly in sun-exposed areas. However, the observation that a considerable proportion of tumours located on the face had only mild elastotic changes suggests that factors beyond UV exposure may influence both elastosis and tumour behaviour [27]. These findings align with our own, indicating that while elastosis is a marker of cumulative sun exposure, it may not be a reliable predictor of surgical completeness in BCC treatment.

Overall, our data contribute to a growing body of literature suggesting that although elastosis reflects the chronic photodamage associated with BCC development, its influence on surgical outcomes such as radicality of excision may be limited. Further research is needed to determine whether elastosis should be considered a meaningful variable in surgical planning for BCC, particularly in high-risk anatomical zones.

Our study did not reveal statistically significant correlations between the radicality of excision and several commonly discussed clinical and histopathological features, including ulceration, inflammation, presence of Demodex mites, grade of elastosis, prior surgeries requiring re-excision, or the presence of other BCC lesions. These findings align with some elements of the existing literature while contrasting with others, highlighting ongoing debate in the field. Ulceration, while often viewed as a marker of tumour aggressiveness, has shown mixed associations with BCC subtype. Cocuz et al. and Yalcin et al. both demonstrated that ulceration is significantly more common in subtypes such as nodular and infiltrative BCC, and less frequent in superficial variants [28, 29]. However, Welsch et al. found no significant association between ulceration and tumour depth, suggesting that ulceration may not consistently reflect biologically aggressive behaviour [30]. Our results echo this ambiguity as no statistically significant correlation was observed between ulceration and BCC subtype (p = 0.089).

The relationship between Demodex folliculorum and BCC remains controversial. While Sánchez España et al. demonstrated an increased risk of periocular BCC in patients with Demodex infestation (OR = 2.99), and Erbagci et al. reported higher mite densities in eyelid BCCs, our study did not confirm any significant association between Demodex and inflammation, BCC subtype, or excision outcome (p = 0.985). This aligns with the conclusions of Talghini et al., who argued that inconsistent findings across studies may stem from methodological heterogeneity and confounding factors such as sampling location and detection techniques [31–33].

Additionally, although previous studies have shown that patients with one BCC are at a substantially higher risk of developing subsequent lesions – with cumulative 5-year risks exceeding 40% (Marzuka and Book) – we did not observe a significant correlation between the presence of other BCCs and radicality of excision [3]. This may reflect the localized nature of surgical planning, where multifocality or prior surgery history does not necessarily influence immediate excision strategy or completeness.

The present results demonstrate that although features such as ulceration, Demodex infestation, and multifocal disease may have theoretical or observational links to tumour biology or recurrence risk, they do not appear to be reliable predictors of surgical radicality in standard excision. This reinforces the primacy of histological subtype and anatomical complexity in determining surgical outcomes, as supported by studies like Kiely and Patel and Cameron et al. [9, 34]. Further large-scale, prospective studies are needed to clarify whether any of these variables might play a more meaningful role in select clinical subgroups.

Dermoscopy has emerged as a valuable tool in the preoperative assessment of basal cell carcinoma, particularly for delineating tumour borders and identifying subclinical extensions that may not be visible to the naked eye. Several studies have demonstrated that dermoscopic margin mapping prior to excision increases the likelihood of achieving clear surgical margins, especially in ill-defined or infiltrative tumours. Reiter et al. reported that the use of dermoscopy improves diagnostic accuracy and helps guide margin determination, reducing the risk of incomplete excision. Despite this, dermoscopy is not yet routinely integrated into surgical planning across all centres, including our own. Incorporating dermoscopic evaluation into standard preoperative workflows may represent a practical and low-cost strategy to improve margin clearance rates and minimize recurrence, particularly in high-risk anatomical zones [35].

CONCLUSIONS

Radical excision of basal cell carcinoma depends primarily on its histological subtype, with aggressive variants demonstrating higher risks of incomplete removal. Other factors such as ulceration, inflammation, and the presence of Demodex mites or elastosis appear to have less predictive value. Preoperative biopsy and thorough surgical planning are essential for achieving optimal outcomes, especially in high-risk anatomical zones of the head and neck.