INTRODUCTION

Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) syndrome is a rare autoimmune disorder affecting brainstem structures and the cerebellum, originally described by Pittock et al. in 2010. Although its etiology remains uncertain, the underlying pathomechanism appears to involve the overactivity of autoreactive T cells, whose target is yet to be identified. Histopathologically, there is lymphocytic infiltration distinctly in the perivascular white matter, but no demyelination is observed. The infiltrate is predominantly composed of CD3+ T cells with a predominance of CD4+ over CD8+, but CD20+ B cells and CD68+ microglia; histiocytes are also present in immunohistochemical staining [1]. Furthermore, studies evaluating the potential association between CLIPPERS and malignancy are still lacking, but it may be reasonable to consider this disease as a paraneoplastic syndrome [2]. Clinical manifestations may vary, but the vast majority of patients present with diplopia, dysarthria and gait ataxia.On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, CLIPPERS is characterized by multiple changes in the midbrain, pons, and cerebellum, usually described as ‘pepper-flake-like’ lesions [3]. Definite diagnosis is based on histopathological examination of a brain biopsy, though a presumable diagnosis can be made based on clinical and radiological features. To date, there is no specific marker for the disease. Moreover, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis remains incoherent amongst CLIPPERS cases, as it can be normal or displaying abnormalities, including elevated protein levels and pleocytosis, as well as the presence of oligoclonal bands [4, 5]. Nonetheless what distinguishes it is a particularly good response to glucocorticoid treatment [4].

We present a case of CLIPPERS syndrome diagnosed on the basis of clinical and radiological features, followed by a comprehensive review of relevant differential diagnoses and their clinical manifestations.

CASE DESCRIPTION

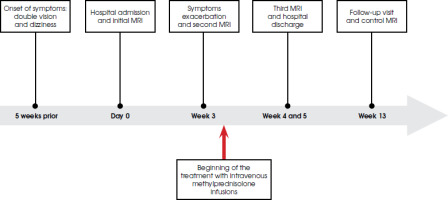

A 65-year-old man presented in July 2023 with double vision and dizziness of approximately five weeks duration prior to hospital admission (the timeline is summarized in Figure I). Additionally, the patient reported recurrent headaches and bilateral facial tingling. The patient was an active smoker (40 pack years) with a history of multiple comorbidities, including: hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, hyperthyroidism with subsequent hypothyroidism (currently euthyreosis without thyroxine replacement therapy), peptic ulcer disease, hypoacusis (following a complicated influenza infection in 2021), and benign prostatic hypertrophy. The patient reported no infections in the past year. He had chronically taken multiple medications, such as bisoprolol, valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide, rosuvastatin, enalapril, omeprazole, and tamsulosin. A review of the current literature indicates no causative evidence linking these medications to the development of CLIPPERS.

On neurological examination upon admission the patient was conscious and fully responsive. Left lateral rectus muscle paresis was noted, resulting in convergent strabismus of the left eye. Moreover, horizontal nystagmus was observed when looking to the right, whereas the patient reported diplopia when looking to the left. Also, scarring and facial asymmetry were observed, which the patient claims are related to a childhood burn on the left side of his face. There was no limb weakness or ataxia, but the Romberg test was positive. Brain MRI with gadolinium, enhancement performed on admission, revealed a T2-weighted hyperintense, ill-defined area in the brainstem, with no evidence of restricted diffusion (Figure II).

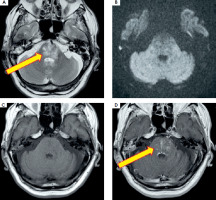

Figure II

The initial brain MRI: T2-weighted hyperintense, diffuse lesion (A), with no features of restricted diffusion in DWI images (B), T1-weighted (C) with gadolinium enhancement revealing heterogeneous disseminated striate areas (D) localized in the lower part of the midbrain and pons in the area of the superior cerebellar peduncles. Images reproduced with kind courtesy of the 2nd Department of Clinical Radiology, Medical University of Warsaw

Further diagnostics included magnetic resonance spectroscopy, which excluded a neoplastic nature and suggested an inflammatory etiology of the lesion. A general examination of the CSF showed an elevated cell count of up to 27 cells/μl and borderline total protein concentration of 39.5 mg/dl. The ESCCA/ISCCA protocol [6] was employed for immunophenotyping analysis of CSF. Specifically, the panel of antibodies used included markers for kappa, lambda, CD45, CD19, CD4, CD10, CD8, CD5, CD14, and CD56. It revealed a predominance of CD4+ T cells, which accounted for 77% of all lymphocytes, followed by CD8+ T cells and CD19+ B cells, each accounting for 10%. Reiber diagrams demonstrated normal blood-brain barrier function. Additionally, type 2 oligoclonal bands were detected in the CSF, using isoelectrofocusing on agarose gel followed by immunofixation with anti-IgG serum on. Two IgG bands were revealed in CSF without any bands in the serum. Testing for onconeural antibodies showed borderline titers of anti- amphiphysin antibodies in blood serum and anti-titin and anti-Zic4 antibodies in the CSF. No circulating serum antibodies to aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) or to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) were found. Tests for serum anti-gangliosides antibodies and a panel of neuronal autoantibodies (NMDA, AMPA, DPPX, GABAR, LG1, CASPR) in both the serum and CSF were negative. Due to borderline titers of anti-amphiphysin, anti-titin and anti-Zic4 antibodies in association with clinical manifestations suggesting a paraneoplastic syndrome, the patient underwent a computed tomography scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis, which showed no significant findings. Moreover, a prostate-specific antigen test was performed, indicating 4,090 ng/ml, which was within normal range. During hospitalization, the patient’s condition deteriorated, with an exacerbation of ocular symptoms and the onset of ataxia in the left lower limb. A follow-up MRI was comparable to the initial scan done upon admission. The patient’s clinical presentation and the MRI features suggested CLIPPERS syndrome. Treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone infusions in a total dose of 7 g over a period of 7 days resulted in significant neurological improvement, with almost complete resolution of the ocular movement symptoms. A further MRI showed regression of the brainstem changes. Continued oral prednisone was started. The initial daily dose was 64 mg for the first consecutive 5 days, with a further reduction to 32 mg for the following weeks. The patient was discharged in good general condition. At the scheduled neurological follow-up at 3 months, the patient reported only dizziness and no other persistent symptoms. On neurological examination, the patient was conscious and fully responsive. Mild bilateral upward restriction of eye movements (right > left) was observed, but the patient did not report diplopia. The check-up MRI showed further regression of the brainstem lesion (Figure III). Upon discharge, the patient was prescribed methylprednisolone at a daily dose of 16 mg, with a plan for gradual reduction of the dosage over time.

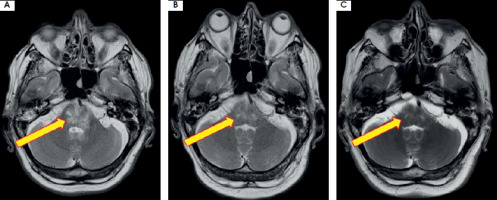

Figure III

Regression of the brainstem lesion presented on T2-weighted images: initial (A), at discharge – week 5 (B), and during follow-up at 3-months (C). Images reproduced with kind courtesy of the 2nd Department of Clinical Radiology, Medical University of Warsaw

The final diagnosis of CLIPPERS syndrome was based on clinical manifestation, laboratory test results, characteristic MRI findings, and a positive response to glucocorticoid therapy.

DISCUSSION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Brainstem encephalitis, as a specific subset of encephalitis, remains an uncommon condition. However, it has a wide range of possible causes. According to a retrospective analysis by Tan et al. [7], CLIPPERS syndrome accounts for approximately 1% of all the causes of brainstem encephalitides. Nonetheless, the exact prevalence and incidence of the syndrome is yet to be determined. To date, over 140 cases have been described, and in 15.7% it was associated with malignancies [8]. Amongst malignancy-associated CLIPPERS syndrome, the majority was related to lymphomas [8]. Therefore, hematological malignancies should be excluded. For instance, in the CLIPPERS case described by Kotlęga et al. [9] the patient had enlargement of the lymph nodes in the left axillary region, hence the authors performed a bone marrow biopsy. Nevertheless, the exact etiology of CLIPPERS syndrome remains uncertain [10]. Most brainstem encephalitis cases are related to autoimmune disorders, but infectious etiology should always be considered in the differential diagnosis [7, 11, 12]. Hence, conditions with similar clinical or radiological manifestations are described below. Although some disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, may involve the brainstem in their course, we have excluded them from the review due to their different clinical course and characteristic lesions on MRI involving other central nervous system (CNS) structures.

Infectious rhombencephalitis

Rhombencephalitis is an inflammatory disease that affects the hindbrain structures – the pons, medulla oblongata and cerebellum. It can be caused by both non- infectious and infectious factors, particularly bacteria and viruses, but also fungi and parasites. The most common infectious factor is Listeria monocytogenes. The other common etiologies include enterovirus 71 and Herpesviridae. Listerial rhombencephalitis has a two-phase course with prodromal flu-like symptoms followed by asymmetric cranial nerve palsy [12]. According to a retrospective analysis by Moragas et al. [13], patients with listerial rhombencephalitis typically present with altered consciousness, fever and meningeal signs, whereas patients with viral rhombencephalitis show no symptoms of meningeal involvement. Radiologically, imaging of listerial rhombencephalitis may vary from hyperintensities on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences to ring-enhancing lesions in the brainstem and cerebellum [14]. Nevertheless, hyperintensities are commonly located at the floor of fourth ventricle [15]. Also, Tyler et al. [16] described a case report of recurrent rhombencephalitis caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection. Their patient complained of double vision and presented with limited upward eyes movement as well as horizontal nystagmus [16]. HSV-related encephalitis may cause a broad spectrum of radiological changes, including brainstem involvement, typically presenting as T2-weighted hyperintensities without diffusion changes or gadolinium enhancement [17]. Additionally, early in the disease course abnormalities may be visible only as DWI hyperintensities, reflecting cytotoxic edema [15]. However, the most characteristic findings involve the temporal and frontal lobes [18]. Therefore, the final diagnosis and treatment of brainstem encephalitis depends on CSF analysis and detection of the etiological factor [12].

Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis

Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis (BBE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by a subacute onset of an altered state of consciousness, bilateral ophthalmoplegia and ataxia, often following an infectious disease. In most cases it is associated with the presence of serum anti-GQ1b antibodies (necessary to confirm a definite diagnosis); however, seronegative BBE is observed in over 30% of patients. Therefore, having excluded other possible conditions, the diagnosis of probable BBE might be established [19]. Furthermore, BBE can manifest in MRI as hyperintense abnormalities on T2-weighted images of the thalamus, brainstem and cerebellum. At first, lesions might resemble those observed in CLIPPERS, but they do not exhibit the characteristic punctate gadolinium enhancement [15]. According to a study by Koga et al. [20], such lesions are present only in 23% of patients with BBE. BBE usually has a favorable outcome and responds well to treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or the combination of IVIG and glucocorticoids [21].

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a rapidly progressing multifocal immune-mediated demyelinating disease of the CNS. This rare disease mainly affects children and is associated with infection or recent vaccination. Typical ADEM presentation – especially in children – is an abruptly evolving, febrile disease with positive meningeal signs. Characteristically, an encephalopathy with behavioral changes and consciousness disturbance might occur, distinguishing ADEM from, for example, an attack of multiple sclerosis [22]. Interestingly, up to 50% of cases may be associated with anti-MOG antibodies [23]. ADEM is characterized by multiple, widespread, asymmetric bilateral lesions throughout the brain in MRI. Nonetheless, isolated brainstem involvement has been described in both pediatric and adult populations [24, 25]. Interestingly, Garkowski et al. [26] reported a case of a 51-year-old woman diagnosed with ADEM following tick-borne encephalitis diagnosed a month earlier. MRI findings included hyperintense contrast-enhancing lesions in both cerebral hemispheres and the pons. Treatment of ADEM is based on glucocorticoid therapy or, alternatively, IVIG and plasmapheresis (PE). The prognosis of ADEM is favorable compared to acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (AHLE), which is a severe form of the disease with a poor prognosis [11].

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein associated disease

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein associated disease (MOGAD) is the most recently described autoimmune demyelinating disease of the CNS. It has long been classified as a nosological entity in the neuromyelitis optica disorders spectrum (NMOSD). The primary pathomechanism in MOGAD is related to autoreactive CD4+ T cells, but given the presence of autoantibodies, the humoral mechanism must also be involved in the disease process. Symptomatically, it is a heterogeneous group of inflammatory disorders affecting the optic nerve with a relapsing course (typically in adults), but it also can manifest as an ADEM-like phenotype (more commonly in children). The disease typically presents with acute, severe flare-ups, radiologically observed as longitudinal extensive T2-lesions of the brain, spinal cord or optic nerves. The lesions can be described as ‘fluffy’ because of their indistinct margins [23]. However, according to Mishael et al. [27], most of the MRI findings are localized in the brainstem, followed by supratentorial and optic nerve lesions. Furthermore, a report by Obeidat et al. [3] seems to be particularly important, highlighting that MOGAD may be a CLIPPERS-mimicking disease, as it may present as isolated brainstem encephalitis with characteristic radiological manifestations. Consequently, all patients suspected of having CLIPPERS should be tested for serum anti-MOG antibodies. Although the acute phase treatment typically involves glucocorticoids, patients with MOGAD may require additional maintenance therapy [23].

Ma2-associated encephalitis and other paraneoplastic syndromes

Brainstem encephalitis may be associated with malignancies and occur as a paraneoplastic syndrome, representing an autoimmune process as a result of the actual anti-tumor immunological response [28]. As a consequence, circulating onconeural antibodies (i.e., anti-Hu, anti-Ma2, anti-Ri) may lead to neuroinflammation and the occurrence of neurological symptoms before the diagnosis of a neoplasm. In most cases with CNS involvement, paraneoplastic syndromes are associated with encephalomyelitis, affecting the entire CNS. Therefore, to date it is challenging to distinguish the particular autoantibodies associated with specific symptoms, as each paraneoplastic syndrome may begin with focal symptoms and secondarily generalize. Anti-Ma2 antibodies seem particularly interesting as they are typically associated with inflammation of the limbic system, hypothalamus, and brainstem [29]. Nevertheless, isolated brainstem encephalitis associated with anti-Ma2 antibodies has been reported, manifesting as a hyperintense T2-weighted lesion in the pons on MRI. The patient presented with slurred speech, dysphagia, and gait instability of subacute onset [30]. Although most cases are associated with germ-cell testicular cancer, anti-Ma2 encephalitis was also described in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and breast cancer [29, 30]. Not only anti-Ma2 antibodies, but also antibodies against amphiphysin may be associated with paraneoplastic isolated brainstem encephalitis. Wang et al. [31] presented the case of a patient with dysphagia and pruritus who was diagnosed with anti- amphiphysin brainstem encephalitis following small-cell lung cancer. The therapy of choice in paraneoplastic syndromes is treatment of the underlying malignancy. Patients with idiopathic autoimmune encephalitides should be treated with glucocorticoids or IVIG [29].

Vasculitis and systemic autoimmune diseases

Vasculitis is a heterogenous group of inflammatory diseases affecting blood vessels of all sizes – arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules and veins. Some of them have a specific tissue distribution, while others are non-organ- specific and affect systemic vessels. According to the International Chapel Hill Consensus, primary CNS vasculitis (PCNSV) is a type of single-organ vasculitis. However, its diagnosis requires the exclusion of systemic vasculitis associated with infectious diseases or autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis or relapsing polychondritis [32]. Recent research by Agarwal et al. [33] has found isolated infratentorial lesions on MRI in only 3.6% of PCNSV patients. In addition, dot-linear enhancement pattern predominated (87%), while only 25.9% of patients had perivascular lesions. Another CNS-affecting vasculitis is Behçet’s disease, which involves both arteries and veins of all sizes. It typically presents as recurrent oral and/or genital ulcers, followed by inflammatory organ changes such as uveitis, gastroenteritis, arthritis or CNS lesions [32, 34]. However, there are reports of patients with primarily neurological symptoms. For example, Mirsattari et al. [34] described the case of a 19-year-old woman presenting with headaches and photophobia, with dominant brainstem lesions in MRI, who was later diagnosed with Behçet’s disease. The most common connective tissue disease associated with CNS vasculitis is systemic lupus erythematosus, which causes vascular hyalinization resulting in microinfarcts [35]. However, according to Fady et al. [36] the lesions are generally located non-specifically in the white matter. Also, CNS involvement might be present in the course of rheumatoid arthritis. For instance, Acewicz et al. [37] presented a case study involving a 68-year-old woman who developed encephalomyelitis, impacting the cerebral peduncles, pons, medulla oblongata, and cervical spinal cord, associated with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Moreover, CNS vasculitis should be differentiated from reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS). The treatment of vasculitis depends on its etiology. If CNS involvement is only part of a systemic disorder, treatment should be based on guidelines for the specific underlying condition, whereas PCNSV is treated with glucocorticoids alone or in combination with cyclophosphamide [38].

CONCLUSIONS

The diagnostic criteria for CLIPPERS syndrome require the exclusion of other potential causes of the patient’s condition [4]. Therefore, it is crucial to consider differential diagnoses, such as infectious rhombencephalitis, BBE, ADEM, MOGAD, vasculitis, and numerous paraneoplastic syndromes. Finally, brainstem encephalitis should be differentiated from primary and metastatic CNS malignancies. Considering the fact that CLIPPERS syndrome is a rare and under-researched condition, it is important to include it in the differential diagnosis of numerous brainstem disorders, especially when the patient exhibits characteristic symptoms and punctate lesions smaller than 3 mm in diameter. As CLIPPERS syndrome is a treatable disease, it cannot be neglected. Further research should be focused on exploration of specific biomarkers to facilitate the diagnostic process.