INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) predominantly affecting young adults, with a significant impact on their quality of life [1]. In most cases, MS onset manifests in individuals between 20 and 40 years old. This MS type with onset in individuals between 18 and 49 years old has traditionally been termed adult-onset multiple sclerosis (AOMS). However, in a minority of cases the onset of the disease can occur in the pediatric population; this MS type has been referred to as pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis (POMS) [2], while the manifestation of symptoms in individuals 50 years of age or older is called late-onset multiple sclerosis (LOMS) [3].

The incidence of MS has risen globally in recent decades [4], with a 2020 study estimating 2.8 million people affected worldwide – a 30% increase since 2013 [5]. In recent decades the age at MS onset has gradually shifted towards later age, with a growing number of late-onset cases. Although the exact causes of this trend remain unclear, several factors have been proposed in the literature. These include shifting exposure to environmental risk factors, sociodemographic changes, heightened clinical awareness of LOMS, broader access to advanced diagnostic tools, and the implementation of newer, more sensitive diagnostic criteria [6-8]. As of 2024, the prevalence of LOMS was estimated to be between 4% and 9.6% of all MS cases [9].

Despite the growing importance and looming challenges associated with LOMS the significance of POMS should not be overlooked. Over the past decade, a plethora of international studies, together with advancements in diagnostic tools, has brought about a significant increase in the number of diagnosed POMS cases, and this trend is expected to continue [10-12]. In various studies, the prevalence of POMS has been estimated at 3-to-10% of all MS cases [13].

Most studies weigh LOMS or POMS against AOMS, yet very few have examined all three forms simultaneously. To address this gap, our study aims to compare clinical and demographic characteristics, differences in disease-modifying therapy (DMT) and comorbidities across all three groups.

METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective study analyzing data from patients diagnosed with MS. The data were obtained from the medical records of patients treated at the University Clinical Center, Medical University of Silesia (Katowice, Poland), including both the polyclinic and the major tertiary referral center. Data were retrieved on January 24, 2024, from clinical records of MS patients admitted to the neurology department affiliated with the center between April 1, 2018, and July 31, 2023. All participants were diagnosed with MS, based on the version of the McDonald criteria that was current at the time of their diagnosis [14-17]. Neurologists trained in MS assessed the patient’s disability scores according to the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [18] at the time of the last follow-up visit within the study period.

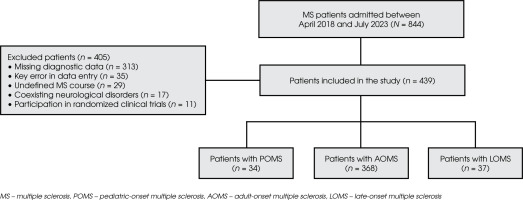

The study included only patients with a complete set of data. Exclusion criteria for the study were: missing diagnostic data in 1 or more of the analyzed domains, key errors in data entry, undefined disease course, neurological disorders coexisting with MS (cerebrovascular disease, other autoimmune CNS disorders, epilepsy, migraine, neurodegenerative diseases, CNS infections, traumatic brain injury, intracranial neoplasms, and major neurodevelopmental disorders), and participation in clinical trials. The study’s flow diagram and the process of patient selection are presented in Figure I.

The group was divided into three subgroups based on the age at MS onset, using cut-off points based on existing literature and international consensus. POMS was defined as disease onset in patients under 18 years old [2]; LOMS as disease onset in patients aged 50 years or older [3]; and AOMS included those whose disease onset occurred between the ages of 18 and 49. The patients’ current EDSS scores reflected their status at the latest follow-up within the analyzed period.

The following data were analyzed: gender, current age, age at MS onset, clinical manifestations at MS onset, age at diagnosis, diagnostic delay, most common comorbidities, course of the disease (categorized into: relapsing remitting MS – RRMS, secondary progressive MS – SPMS, and primary progressive MS – PPMS), number of patients with moderate disability (EDSS score ≥ 4 and < 6) and severe disability (EDSS ≥ 6), overall EDSS score at the last follow-up, EDSS functional systems score at the last follow-up, total number of prescribed DMT drugs, duration of treatment with first-line DMT drug (interferon beta, glatiramer acetate, dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide [19]), number of patients switching to a second-line DMT drug (natalizumab, alemtuzumab, ocrelizumab, cladribine and fingolimod [19]), and reasons for switching. Treatment intolerance was defined as a patient’s inability to continue DMT therapy due to reported severe or persistent side effects regardless of disease-modifying benefits. Adverse drug reaction (ADR) was defined as a harmful, unintended response to a DMT drug occurring at normal doses, which may be unpredictable and independent of the drug’s intended therapeutic effect. Loss of treatment efficacy was defined as a confirmed increase in disease activity despite adherence to a prescribed DMT, as evidenced by at least one of the following: the occurrence of a relapse; confirmed radiological progression during follow-up; or a sustained progression of disability, defined as a sustained increase in EDSS scores between adjacent follow-up visits. The classification of DMT drugs was based on the principles of the Polish National Health Fund (NFZ) drug program for MS treatment in Poland. Data regarding the number of relapses and clinical manifestations of MS relapses were also analyzed and are presented in the supplementary data.

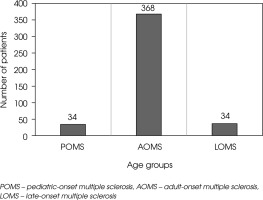

Figure II

Number of patients included in the study, categorized by age at MS onset into POMS, AOMS, and LOMS groups

For continuous variables, means and standard deviations (SD) were reported, while for categorical variables distributions and frequencies were presented. The Shapiro-Wilk test assessed the normality of continuous data within the groups studied. Based on the test results, ANOVA was applied for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed data. For categorical variables, chi-square (χ²) and Fisher’s Exact tests were applied where appropriate, with Bonferroni-Holm corrections for p-values to account for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica® software (version 13.3, StatSoft, USA, 2013), and the level of significance was set at α < 0.05.

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, based on existing medical records, ethical committee approval was not required. Confidentiality and data safety were ensured, and the study was conducted according to the ethical principles outlined in the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

From a sample of 844 patients, a total of 439 MS patients were included in the statistical analysis. The participants were grouped as follows: 34 (7.74%) with POMS, 37 (8.43%) with LOMS and 368 (83.83%) with AOMS, as presented in Figure II.

Basic demographic and clinical features of the POMS, AOMS and LOMS groups

Basic demographic and clinical features of POMS, AOMS and LOMS groups are presented in Table 1.

Females constituted the majority in all groups, though the LOMS group had a significantly higher proportion of male patients compared to the other groups (p = 0.044). The duration of the disease was longest in the LOMS group. Diagnostic delay increased significantly with age (p < 0.001).

Motor dysfunction was the most prevalent clinical manifestation at disease onset in the LOMS group, occurring significantly more frequently when compared to the AOMS and POMS groups (p = 0.017). Sensory and visual disturbances were more commonly observed in the AOMS and POMS groups compared to LOMS. Cerebellar and brainstem symptoms were rare across all groups, while multisystem involvement was uniformly distributed among the three groups (p = 0.017).

Hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity in the LOMS group and was significantly more common compared to the AOMS and POMS groups (p < 0.001). Hyperlipidemia was also more prevalent in LOMS compared to the other groups (p = 0.002). Osteoarthritis occurred more frequently in LOMS than in AOMS and was not observed in POMS (p = 0.001). Type 1 diabetes was significantly more prevalent in LOMS compared to AOMS and POMS (p = 0.011). Other comorbidities showed no significant differences between the groups.

Overview of the course of the disease in the POMS, AOMS, and LOMS groups

Table 2 provides an overview of course of the disease, EDSS and ambulation scores in POMS, AOMS, and LOMS groups.

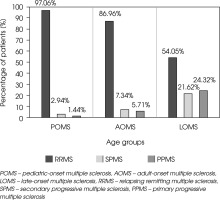

RRMS was the most common course of the disease across all groups (p < 0.001). The prevalence of PPMS and SPMS increased with age, being highest in the LOMS group compared to AOMS and POMS (p < 0.001). SPMS was observed least frequently in POMS, followed by AOMS, and was most prevalent in LOMS (p < 0.001). Similarly, PPMS was absent in POMS, less frequent in AOMS, and significantly more common in LOMS (p < 0.001). The distribution of MS types in each group is shown in Figure III.

Table 1

Demographic and basic clinical characteristics of POMS, AOMS and LOMS patients

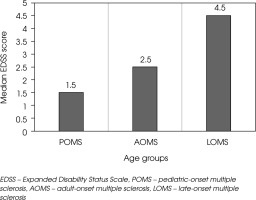

EDSS and ambulation scores in the POMS, AOMS, and LOMS groups

At the last follow-up, patients in the LOMS group were significantly more likely to have a moderate disability (EDSS score ≥ 4 and < 6) compared to those in the AOMS and POMS groups (p < 0.001). Severe disability, defined as an EDSS score ≥ 6, was also more prevalent in the LOMS group than in the AOMS and POMS groups (p = 0.017). The median EDSS score at the last follow-up increased progressively with age, being highest in the LOMS group, followed by AOMS, and lowest in POMS (p < 0.001) as presented in Figure IV.

Significant differences in EDSS functional system scores were observed across several systems. At the last follow-up, pyramidal scores were highest in the LOMS group, followed by AOMS and POMS (p < 0.001). Cerebellar scores were also significantly elevated in LOMS compared to AOMS and POMS (p = 0.040). For brainstem functions, scores were highest in LOMS, intermediate in AOMS, and lowest in POMS (p = 0.036). Sensory function scores showed a similar pattern, with the highest scores in LOMS, followed by AOMS and POMS (p = 0.010). No significant differences were observed in scores for bowel and bladder function, visual function, or cerebral functions (p > 0.05). The EDSS ambulation score increased progressively with age at MS onset, being highest in LOMS, intermediate in AOMS, and lowest in POMS (p < 0.001).

Characteristics of disease-modifying therapy and its changes in POMS, AOMS and LOMS

Characteristics of DMT and its changes in POMS, AOMS and LOMS patients are provided in Table 3.

Table 2

Course of the disease, overall EDSS score, EDSS functional systems score and ambulation score between POMS, AOMS and LOMS patients

Figure III

MS types in the POMS, AOMS, and LOMS groups at the last follow-up. The percentage of patients with RRMS, SPMS, and PPMS in each group is shown

The mean total number of DMT drugs taken per patient decreased with age at onset, being highest in POMS, followed by AOMS, and lowest in LOMS (p = 0.002). Treatment duration with first-line agents increased progressively from POMS to AOMS and was longest in the LOMS group (p = 0.004). Switching to a second-line DMT was significantly more frequent in the POMS group compared to AOMS and LOMS (p = 0.001).

The reasons for switching therapies varied significantly across groups (p = 0.005). Adverse effects as a reason for switching were similarly frequent in POMS and LOMS but less common in AOMS. Treatment intolerance was more frequently cited in AOMS, followed by POMS, and was least common in LOMS. Patient requests were rare and reported only in AOMS. Loss of treatment efficacy was the most common reason in all groups and was highest in LOMS, followed by POMS, and lowest in AOMS. Other reasons for switching were most frequent in AOMS and less common in POMS and LOMS.

Table 3

Characteristics of the disease-modifying therapy and its changes between POMS, AOMS and LOMS patients

Data regarding the number of relapses and clinical characteristics in RRMS patients is available in the Supplementary Table 1.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to compare clinical and demographic differences in MS patients with different ages of onset in the Central European population, an issue that has gained particular importance as the number of MS patients with both pediatric and late onset continues to rise globally.

In our research, the LOMS group showed a higher proportion of male patients compared to female patients, which is consistent with previous studies that have also documented a higher prevalence of males affected with LOMS [20-23]. The impact of gender on the clinical course and progression of disability in LOMS has been extensively studied in the literature. Previous studies have linked being male with a poorer prognosis and faster disability accumulation in the LOMS group [24-26]. In comparison, the two younger groups showed a lower proportion of male patients, with percentages aligning with those reported in other studies [10, 21, 27, 28]. This finding suggests that being male might play a more significant role in the course of the disease and prognosis as the onset of MS occurs later in life.

The shortest diagnostic delay was observed in the POMS group, which is consistent with some previous studies indicating that a younger age of onset, combined with a more active relapsing phenotype of MS, prompts quicker medical consultation and diagnosis [29-31]. However, other studies have reported a longer diagnostic delay in POMS compared to AOMS [32]. This discrepancy may be attributed to several factors, including variability in access to healthcare, physician awareness of POMS, the evolving diagnostic criteria for POMS, variations in the timeframe analyzed in different studies, and the increasing availability of better diagnostic tools over time [33]. The longest diagnostic delay in our study occurred in the LOMS group, which may be due to a combination of factors, including insufficient awareness of MS among older adults and the potential for MS symptoms to be mistaken for other age-related conditions, thus significantly contributing to diagnostic delays [34]. Additionally, older patients often tend to seek less medical advice, and their more complex clinical presentation can further complicate diagnosis [34]. Previous research has also shown that diagnostic delays are significantly longer for patients with PPMS compared to those with RRMS or SPMS. Since PPMS is particularly common in older individuals, this may be a contributing factor to the longer diagnostic delays observed in some of the LOMS patients [35].

Motor symptoms at onset were significantly correlated with older age, being highest in the LOMS group, while showing a similar distribution in the two younger groups. This observation is largely consistent with previous studies that identified motor dysfunction as the most common initial manifestation among LOMS patients [3, 36-38]. This result is particularly significant, as prior research has shown that motor dysfunction, along with older age at MS onset, correlates with longer diagnostic delays and more rapid disability accumulation [29, 38, 39]. In our study, visual impairment and sensory dysfunction were more prevalent in AOMS and POMS. These findings align with previous research, which has demonstrated that sensory and visual involvement are more likely to occur at a younger age [6, 21, 28, 35]. While multisystem symptoms showed a similar distribution across the three groups, broad variations in classification are noted in the literature. Some studies classify them as a distinct category [9, 21], while others do not [28, 36, 38]. Methodological differences and potential biases of neurologists may also influence the categorization of symptoms; therefore, the interpretation should be approached with caution.

In the present analysis, hypertension and hyperlipidemia were the most common comorbidities, with the LOMS group being particularly affected, which aligns with previous large cross-sectional research showing that hypertension is 25% more common in people with MS than in the non-MS population [40]. The higher prevalence of hypertension and hyperlipidemia in the LOMS group can likely be attributed to age-related factors [34]. The higher burden of these comorbidities in MS may be partly related to dysregulated inflammatory processes, along with factors such as physical inactivity, socioeconomic marginalization, and other health and social barriers, making their effective management critical to improving patient outcomes [41].

We have demonstrated that, despite the relapsing-remitting course being the most frequent disease trajectory regardless of age at MS onset, the proportion of patients with progressive courses (PPMS, SPMS) increased with advancing age. This finding is largely consistent with previous research [21-23, 36, 37, 42]. A higher proportion of progressive courses in LOMS patients could be attributed to several mechanisms, including immunosenescence, different cytokine expressions, diminished remyelination capacity, and reduced oligodendrocyte function [43]. The neurodegenerative component has been shown to be particularly significant in aging MS patients, who exhibit a lower level of neuroinflammation compared to AOMS and POMS patients, which may contribute to the progressive course of the disease [42]. In contrast, the highest percentage of RRMS was observed in POMS patients, which aligns with previous research, demonstrating that in patients with MS onset under 18 years old, RRMS tends to be the dominant course of the disease [12, 45, 46].

The EDSS score at the last follow-up in our study varied according to the age of MS onset. POMS patients demonstrated the lowest EDSS scores, while the LOMS group showed the highest, with AOMS patients displaying intermediate scores. This pattern of elevated EDSS scores in the LOMS group aligns with findings from previous studies, which similarly reported the highest levels of disability in the LOMS group. In contrast, individuals with POMS consistently exhibited the lowest EDSS scores, indicating a slower disability progression compared to adult- and late-onset cases [3, 21, 36, 42]. The higher EDSS values observed in the LOMS group at the last follow-up, compared to the POMS and AOMS groups, can be attributed to several factors, including longer diagnostic delays and a faster rate of disability progression in older individuals. For example, a study conducted on the Brazilian population demonstrated that 25.8% of LOMS patients reached an EDSS level of 6.0 at their last follow-up. The median time to reach an EDSS of 6.0 was 5.1 years for LOMS patients, compared to 6.8 years for those with younger-onset MS [3]. Other research indicated that LOMS patients experienced a more rapid and pronounced increase in EDSS scores from the first clinical visit, whereas AOMS patients with comparable disease duration showed significantly lower EDSS scores [47]. In contrast to the accelerated progression of disability observed in LOMS patients, a study comparing POMS and AOMS groups revealed that disability progression was notably slower in POMS patients, as evidenced by consistently lower EDSS scores over time. At the start of DMT therapy, AOMS patients had a higher baseline EDSS (2.45 vs. 1.56 in POMS), and after more than 10 years of disease duration, AOMS patients reached an average EDSS of 3.74 compared to 2.44 in POMS [48]. Similar findings were obtained another study comparing POMS and AOMS groups, where disability progression was slower in POMS patients. At the end of the observational period, the mean EDSS score was significantly lower in POMS (2.38 vs. 3.02 in AOMS) [49].

The reasons for the more severe progression of disability and higher EDSS scores in older MS patients, compared to younger groups, may be attributed to age-related factors such as intensified neurodegenerative processes, chronic low-grade neuroinflammation, and a higher prevalence of vascular comorbidities, all of which may accelerate the progression of disability in older individuals [49]. In contrast, younger patients may experience lower levels of disability due to an enhanced capacity for remyelination and more effective myelin repair mechanisms. Additionally, while younger individuals often exhibit a heightened pro-inflammatory response, their recovery mechanisms and efficient remyelination processes may promote better functional outcomes than those observed in older individuals, despite an inflammatory environment [50]. However, it has been noted that despite a slower progression of disability, due to the onset at a younger age, POMS patients often reach significant disability milestones at an earlier age than those with AOMS and LOMS, which may actually worsen their long-term prognosis [51].

In our study, the LOMS group had the lowest number of DMT drugs taken per patient and the longest duration of first-line treatment. These findings are consistent with prior research, which suggests that patients in this group are less frequently prescribed DMT than the POMS and AOMS groups and are less often exposed to high-efficacy DMT therapies [23, 34, 52]. We also managed to establish that switching to the second-line DMT drug is more common in the POMS and AOMS patients in comparison to the LOMS group. Research highlights that younger patients, particularly those with POMS, often experience more relapses and inflammatory activity, which prompts clinicians to switch to more potent second-line DMTs to better manage the disease. Conversely, LOMS patients tend to show a more gradual progression of the disease, accompanied by age-related comorbidities and polypharmacy, which often results in a lower frequency of switching to second-line treatment [3, 21, 47, 51]. It is also worth mentioning the effect of a patient’s age on the efficacy of treatment; as one meta-analysis suggests, there are no forecasted benefits from the use of immunomodulatory drugs after the age of 53 [54]. The reason for switching to second-line DMT drugs also varies between groups – adverse effects were most common in the POMS and LOMS groups. This tendency in both groups is often due to the unique challenges posed by these age-related forms of MS. For instance, younger patients with POMS may face distinct side effects impacting lifestyle, while older patients with LOMS may experience a higher risk of complications due to comorbidities and age-related factors [55]. Loss of treatment efficacy was the most common reason for switching to second-line DMT drugs in each group; this finding is consistent with existing research [56-59].

Several limitations of this study should be considered. Its retrospective design is prone to recall bias, particularly concerning the exact date of disease onset and the time lapse between onset and proper diagnosis by a neurologist. Additionally, the retrospective nature of the study limited the interpretation of some data, reducing the sample size due to gaps and errors in the analyzed data. Moreover, the data come from a single research center, limiting the study’s representativeness, as multi-center studies encompass more diverse patient populations and provide larger sample sizes, which enhances statistical power and reduces the risk of systematic errors related to local practices or protocols. The evolution of MS diagnostic criteria over time presents an additional methodological challenge. The McDonald criteria have undergone multiple revisions, altering the diagnostic threshold and potentially influencing the definition of patient cohorts across different study periods. However, to our knowledge previous studies have not accounted for the distinct versions of the McDonald criteria used at the time of diagnosis. Consequently, the impact of these differences on the groups studied remains unclear. This limitation is inherent to all prior studies in the field and requires further research. The cut-off ages for LOMS, AOMS and POMS, although chosen on the basis of the current literature, remain somewhat arbitrary due to the lack of internationally accepted guidelines and universally recognized cut-off points for POMS, AOMS, and LOMS. Although our study classified DMTs according to the Polish National Health Program, the variable accessibility of DMTs over different periods may have influenced the disease course. Similar studies in literature have not conducted comprehensive analyses of these potentially confounding factors, such as stratifying patients based on the phases of DMT availability or adjusting for differences in accessibility to treatment over time. This omission is a limitation not only in our study but also in previous research in this field. Differences between populations from different countries, each with varying therapeutic standards and strategies, further complicate the universal applicability of the findings. The development and increased accessibility of diagnostic tools, along with the introduction of newer diagnostic criteria, may also lead to discrepancies between this study’s results and those from older studies or patients diagnosed in earlier periods.

CONCLUSIONS

In our study, distinct clinical, demographic, and treatment patterns emerged among the POMS, AOMS, and LOMS groups. Compared to the other groups, LOMS patients were more frequently male, presented more often with progressive types of MS, had a higher prevalence of motor symptoms at onset, significantly longer diagnostic delays and showed the highest EDSS scores at last follow-up. In contrast to older groups, POMS patients had the highest percentage of relapsing-remitting MS, the shortest diagnostic delay, a higher proportion of visual symptoms at onset, and the lowest EDSS scores at last follow-up. Comorbidities, particularly hypertension and hyperlipidemia, were most common in the LOMS group. The usage of DMT drugs also differed between groups, with LOMS patients using fewer of them, remaining on first-line therapies for longer durations and switching less often to second-line therapies. In contrast, POMS patients had the shortest durations on first-line therapies and showed the highest tendency to switch to second-line DMT drugs.