INTRODUCTION

Prurigo pigmentosa (PP) is a rare inflammatory skin condition of unknown etiology that results in confluent erythematous papules which form a reticular pattern, most commonly observed on the skin of the back, chest and neck. These erythematous papules subside with residual reticulate hyperpigmentation [1]. Despite its unconfirmed etiology, multiple inducing factors have been linked to its incidence, including hormonal, infectious and even metabolic conditions like ketosis, the state in which ketone bodies present in the serum in an elevated concentration are the organism’s energy source [2].

OBJECTIVE

We present the case of a 29-year-old male with prurigo pigmentosa confirmed with a histopathological examination. The condition, induced by a ketogenic diet, was subsequently successfully treated with lymecycline and ketogenic diet discontinuation.

CASE REPORT

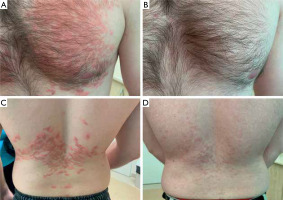

A 29-year-old male with no pre-existing conditions was referred to the dermatology department due to erythematous papular skin lesions that appeared 2 weeks after the introduction of the ketogenic diet by the patient. Prior to the onset, the patient had not suffered from any skin conditions. Upon admission the patient (figs. 1 A, C). presented with coalescing papules and macules that formed a reticulate pattern on his chest and lower back. Topical steroids and emollients were used prior to admission with no improvement. Family history of skin diseases was negative. During the patient’s stay at the hospital a skin biopsy was performed, and blood samples were collected for laboratory and serological tests, with negative Borrelia IgG, IgM, total protein and protein electrophoresis within laboratory norms.

Figure 1

The patient’s lesions on admission (A, C) and a month after the treatment and dietary intervention (B, D)

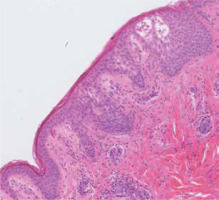

Suspecting prurigo pigmentosa (PP), a 300 mg daily dose of oral lymecycline was introduced and the patient was advised to discontinue the ketogenic diet. Histopathological findings in the epidermis included spongiosis and eosinophils located in small vesicles as well as perivascular neutrophilic infiltrates in the dermis (fig. 2).

Figure 2

The patient’s histology specimen exhibiting spongiosis as well as eosinophilic and neutrophilic infiltrates characteristic for early-stage lesions for prurigo pigmentosa

The patient has returned after a month of treatment and return to a standard diet with no reduced carbohydrate intake. Upon examination his lesions have faded considerably with residual patches of hyperpigmentation (figs. 1 B, D). During follow-up visits over the next 6 months, no relapse was observed.

DISCUSSION

Prurigo pigmentosa has been reported for the first time in 1971 by Masaji Nagashima and co-workers from the Kyoto University in Japan [3]. It is most commonly observed in young female adults, with the median age of 24 years of age, with typical locations of the lesions involving the torso (approximately 60% of cases) and neck (approximately 30% of cases), with other areas of the body being less frequently reported [4].

The association between PP and ketogenic diet, specifically the state of ketosis that is the goal of this diet, is widely discussed in the literature [2]. New case reports that highlight this cause-and-effect sequence emerge, stressing the importance of the prompt dietary intervention and the significance of being familiar with the condition’s clinical presentation taking the increasing popularity of ketogenic diets into account [4–7].

A link between H. pylori gastritis and PP has also been reported [8–10]. One case study has reported the presence of H. pylori in hair follicles in the patient’s skin lesion biopsy. This patient suffered from H. pylori gastritis and both his gastrological and skin problems were treated successfully with an antibiotic regimen [9].

It is important to note that ketogenic diets have experienced a surge in popularity. Purposeful introduction of ketosis by drastically reducing carbohydrate intake and substantially increasing fat and protein consumption with the aim of achieving weight loss and improving glucose tolerance is more and more common. The market of ketogenic diets was reported to be valued at almost 10 billion dollars in 2019, and its value is expected to rise even further [11].

According to numerous sources, this results in an increased incidence of PP worldwide, in the past observed mainly in the Japanese population [12]. In clinical settings, possessing applicable knowledge is paramount to tackle this condition especially since ketogenic diet is often used without professional supervision, and easily accessible Internet sources patients may use to self-diagnose and self-treat are oftentimes not credible, even dangerous [5].

The diagnosis of PP requires a clinico-pathological correlation, and obtaining a skin biopsy for histopathological examination has additional diagnostic value. Different conditions are suspected on the different stages of lesion evolution. Early stages may resemble dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, Grover’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, or even psoriasis. When the lesions are fully developed, they should be clinically differentiated from erythema multiforme and PLEVA. After subsiding, the literature points to diseases in the course of which residual hyperpigmentation occurs such as Gougerot-Carteaud’s disease, macular amyloidosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, or lichen planus pigmentosa [4, 8].

Histopathological findings in PP differ with the stage of the disease – early lesions exhibit superficial, perivascular neutrophilic infiltrates and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis with mild spongiosis, and later-stage lesions are described as parakeratotic, with infiltrates mainly comprised of lymphocytes and melanophages [8].

The treatment of prurigo pigmentosa has not yet been standardized, and no clinical studies have been conducted to assess the effectiveness of drugs used in this condition, with treatment regimens extrapolated mainly from published clinical cases and literature reviews. Pharmacological interventions should be introduced before obtaining the histopathological confirmation as the findings may not be conclusive. Tetracycline group antibiotics, effective in PP by inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis, are most commonly used in PP, especially minocycline, which is the firstline therapy in the United States, but also doxycycline and tetracycline [1, 4]. Another suitable therapeutic option is dapsone [8]. Topical steroids do not impact the course of the condition positively [1]. If there are pre-existing factors that may cause the onset of PP, their identification and elimination are key in managing this condition.

CONCLUSIONS

Due to the increasing popularity of the ketogenic diet, it is more than likely that ketosis-induced prurigo pigmentosa will be more widely observed in dermatologists’ offices. Increasing awareness of this disease and its relationship with the ketogenic diet as well as other etiological factors may result in better chances of proper diagnosis and improved treatment outcomes.