INTRODUCTION

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease (MOGAD) is a recently recognized, rare, autoimmune, inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS), distinct from neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) and multiple sclerosis (MS) [1, 2]. The recently estimated worldwide prevalence of MOGAD is approximately 1.-2.5 per 100,000, with around 30% of cases occurring in the pediatric population and a median age at onset of around 28-30 years [3]. MOGAD presents a heterogeneous clinical spectrum, encompassing optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM), cortical encephalitis, brainstem encephalitis, and meningitis [1, 2]. Previous studies have demonstrated that its clinical phenotype varies depending on age at disease onset, following a distinct age-dependent pattern [3, 4]; approximately 30% of cases occur in the pediatric population, where it accounts for 35-40% of acquired CNS demyelinating syndromes. ADEM manifests most frequently in children under the age of 10 years, whereas myelitis and brainstem encephalitis are more frequently observed in adults. Optic neuritis represents the most common initial manifestation across all age groups, occurring in approximately 40% of cases. Furthermore, 35-50% of early-onset patients demonstrate a relapsing disease course, with a marginally elevated relapse rate of approximately 60% observed in those with adult-onset disease [1, 2]. Based on the age at onset, MOGAD has been classified into pediatric-onset (PO-MOGAD), adult-onset (AO-MOGAD), and late-onset MOGAD (LO-MOGAD), the latter defined as disease onset at or after the age of 50 [5,6]. While most studies to date have focused on younger-onset forms, LO-MOGAD remains an underrecognized entity, with relatively few studies dedicated to the population of older patients [5, 6]. However, with the ageing of societies and the rising incidence of autoimmune diseases among the elderly, there is an increasing need to focus on and better understand LO-MOGAD.

In this paper, we present the case of a multimorbid elderly patient with an initial manifestation after the age of 50, presenting severe bilateral optic neuritis and a high risk of complete vision loss, followed by an extensive follow-up period. In the present literature review, we summarize reports and studies that, to date, have focused solely on the late-onset form of the disease, discussing the most significant differences between early-and late-onset MOGAD, their implications in clinical practice, and their possible underlying causes. We aim to underscore the distinctiveness of LO-MOGAD, as most studies have focused on younger-onset forms, which differ substantially from the late-onset presentation.

CASE DESCRIPTION

Patient’s history prior to admission

In 2019, a 55-year-old male patient was admitted to our neurology department due to progressive bilateral vision loss. Over the preceding two years, he had experienced declining visual acuity related to severe cataract and glaucoma. Following cataract surgery in 2018, transient visual improvement was noted but was later complicated by retinal detachment and permanent blindness in the right eye. In the 3-5 months prior to admission, the patient experienced a progressive loss of visual acuity in the left eye, unrelated to pre-existing ocular conditions, progressing to nearly complete blindness. Following an inconclusive ophthalmological evaluation, the patient was referred to our department for further diagnostic workup. A broad differential diagnosis was considered, including infectious, paraneoplastic, and autoimmune causes, as discussed below. Figure I provides a visual outline of the clinical timeline but is not intended to detail specific diagnostic or therapeutic procedures.

Clinical presentation upon admission

On admission, the patient was in a moderate condition, presenting with profound blindness in the left eye, and progressive deterioration of vision. Additionally, the patient complained of persistent, chronic holocephalic headache with retrobulbar pain in the right eye and dizziness for the past 3 months, unrelated to posture, diurnal variation, or medication. The neurological examination was largely unremarkable, except for a significantly reduced visual acuity score (VAS; 20/100) in the left eye with peripheral field restriction and central vision preservation, as well as blindness in the right eye (LP – light perception only). Fundoscopy showed no optic disc edema.

Figure I

Timeline of the disease course with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-immunoglobulin G (IgG) titers, visual acuity and treatment interventions from disease onset to follow-up

The patient exhibited several age-related comorbidities, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, degenerative disc disease, monoclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) kappa gammopathy (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance – MGUS), amyloidosis, glaucoma, cataract, and restless legs syndrome. He had previously undergone a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The patient denied using any stimulants, smoking, or regular alcohol consumption. He was on a regular medication regimen, which included metformin (1000 mg, once daily), torasemide (5 mg, once daily), lisinopril/amlodipine (10 mg/5 mg, once daily), a potassium supplement, and acetylsalicylic acid (75 mg, once daily). Additionally, the patient used eye drops and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, periodically.

Brain MRI and visual evoked potentials – findings

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed bilateral longitudinally extensive optic neuritis (LEON), with mild vasogenic edema, especially around the right optic nerve with bilateral perineural sheath enhancement (Figure II). Additionally, multiple diffuse bilateral T2 hyperintensities were observed, localized in the supratentorial deep white matter and periventricular matter, with extensive involvement of the periventricular white matter of the bilateral posterior and inferior horns of the lateral ventricles. These lesions were poorly demarcated, non-enhancing, and showed no restricted diffusion (Figure III.A1-4). Pattern-reversal visual evoke potentials (reversal-P-VEP) for the left eye (right eye deeply impaired) showed a significant delay of the P100 wave latency and a reduction in the amplitude of this wave compared to the normal values for the patient’s age (Figure IV).

Diagnostic workup and initiation of treatment

A comprehensive differential diagnostic workup was conducted, considering infectious, paraneoplastic, and autoimmune etiologies.

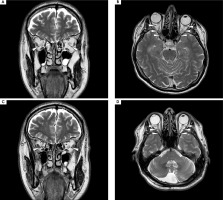

Figure II

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, T2 sequence. A, C) Coronal projection at different slices: bilateral optic nerve sheath enhancement is observed in the segment running through the optic nerve canal. B, D) Axial projection: bilateral longitudinal enhancement of the optic nerves in the retrobulbar segment, extending to optic chiasm and bilateral perineural sheath enhancement. No contrast enhancement was observed

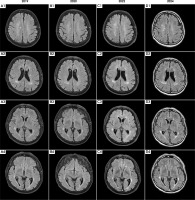

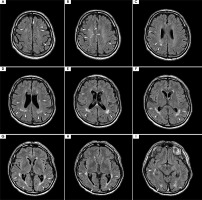

Figure III

Time evolution of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abnormalities. Axial projection; T2-weighted sequences (2019, 2020, 2022) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence (2024). The MRI scan performed in 2019 during the patient’s initial visit, along with follow-up MRIs in 2020, 2022, and the latest in 2024, are shown. In 2019 (A1-4), multiple, poorly demarcated supratentorial hyperintensities were observed bilaterally in the deep white matter and periventricular areas. The lesions did not become enhanced after contrast and showed no diffusion restriction. As shown in the follow-up MRI scans from 2020 (B1-4), 2022 (C1-4), and 2024 (D1-4), despite acute and maintenance treatment being initiated and a regression of ophthalmological symptoms, the lesions exhibited minimal temporal evolution throughout the follow-up period. No new lesions appeared between subsequent hospitalizations

Serological testing for autoimmune demyelinating diseases revealed the presence of MOG-IgG antibodies at a titer of 1 : 80 (fixed cell-based assay (FCBA), Euroimmun Germany), and the absence of antibodies against aquaporin-4 (AQP4) in the serum. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a mildly elevated albumin CSF/serum ratio, suggesting minor blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, though without pleocytosis or oligoclonal bands. CSF analysis showed no evidence of active intrathecal inflammation, with the glucose concentration, leukocyte count, and IgG index all within normal values. No pleocytosis or oligoclonal bands (OCBs) were present.

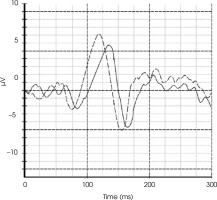

Figure IV

Reversal-pattern visual evoked potential (P-VEP) chart of our patient, compared with the representative chart of a healthy individual of the same age and gender for the left eye. The test revealed a significant delay in the P100 wave and a reduction in its amplitude. The illustrative graph shows the VEP test findings of our patient (solid line) and a healthy individual (dashed line). The prolongation of latency and the decrease in P100 amplitude indicate permanent damage to the visual pathway with a loss of visual fibers

Routine laboratory tests revealed no abnormalities. Inflammatory markers were within the normal range and serological screening for Lyme disease spirochete was negative. Extensive paraneoplastic screening included testing for onconeural antibodies using immunoblot techniques, all of which were negative. Additionally, serum tumor markers were within reference ranges. Whole-body computed tomography excluded malignancy. Conversely, autoimmune encephalitis testing also produced negative results.

Based on the exclusion of other more likely etiologies, a preliminary diagnosis of late-onset MOGAD was made. The findings in this case support a diagnosis of MOGAD rather than MS or NMOSD for several reasons. Initially, serological testing yielded negative results for AQP4-IgG antibodies, effectively excluding AQP4-positive NMOSD. Secondly, the analysis of CSF did not reveal any evidence of intrathecal inflammation. Notably, the absence of OCBs is consistent with a diagnosis of MS, in which OCBs are typically present in over 85% of cases. Furthermore, the absence of pleocytosis and the normal IgG index served to further reduce the likelihood of MS or AQP4-positive NMOSD. Despite the presence of a mildly elevated albumin CSF/serum ratio, indicative of a minor disruption of the BBB, this finding is non-specific and can be observed in MOGAD.

The patient received acute treatment via intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) at a dose of 1000 mg daily for 5 consecutive days (total cumulative dose: 5 g), with a gradual improvement in visual acuity, as evidenced by vision acuity tests. The patient was discharged home with minor residual vision loss and prescribed maintenance therapy of oral corticosteroid (oCS) (prednisone 40 mg per day).

Six-month follow-up: clinical and radiological findings

Six months later, in 2020, the patient was admitted for a follow-up visit. The maintenance treatment with oCS was satisfactory, with no progression of visual loss. In the neurological examination, VAS in the left eye was consistent with the previous assessment at discharge (≥ 20/40), with blindness in the right eye (LP). Tendon reflexes were diminished in both upper limbs and elevated in the lower limbs, without any paresis or hypoesthesia. Given the potential spinal abnormality, a follow-up MRI of the brain and spinal cord was performed. Follow-up MRI of the brain showed no new lesions, no contrast enhancement, and minimal changes from the previous scan (see Figure I.B1-4). The spinal MRI revealed a short-segment lesion at the level C3-C4, with the extensive involvement of gray matter on a transverse section and an “H sign”, consistent with short-segment transverse myelitis (see Figure V).

Despite the extensive cervical spine involvement, the patient exhibited very minimal neurological deficits, which were less significant than would be expected from the MRI findings. Serum MOG-IgG testing showed the low-positive values at a titer of 1 : 20. Given the absence of progressing visual disability, restoration of visual acuity with maintenance treatment, and minimal radiological progression of previous lesions, as well as considering the potential side effects of oCS, multimorbidity, and the patient’s advanced age, a gradual tapering of the treatment was initiated over the following months.

FOLLOW-UP IN 2021: DISEASE RELAPSE DURING CORTICOSTEROID TAPERING AND INITIATION OF IVIG THERAPY

During follow-up in early 2021, a recurrence of visual symptoms and increased MOG-IgG titers despite corticosteroid tapering prompted an escalation of therapy. During the process of corticosteroid tapering, the patient was readmitted on an emergency basis due to a gradual decline in left eye VAS (20/50). Despite a minimal evolution of the radiological picture, with no new contrast-enhancing lesions, serum MOG-IgG testing revealed an increase in titer to 1 : 40. A definitive diagnosis of late-onset MOGAD was established on the basis of the following: a prominent therapeutic response to and dependence on corticosteroids; a constellation of symptoms; the persistence of serum MOG-IgG; and the correlation of these with the recurrence of symptoms. Considering the safety profile and efficacy of other maintenance treatments, and given the patient’s age, comorbidities, and polypharmacy, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy was chosen. Rituximab and tocilizumab were not selected due to multiple factors, as discussed in detail in the discussion section. Since then, the patient has received IVIG infusions every 4-6 weeks. Each cycle consisted of 120-180 g (approximately 2 g/kg of body weight), administered over 3-5 consecutive days. Treatment was initiated with higher doses (approximately 180 g), which were gradually reduced to around 120 g based on body weight and clinical response. The initial course of treatment was satisfactory, with no progression of vision loss and good treatment tolerance. However, attempts to extend the intervals between IVIG infusions, at the patient’s request, to more than 7 weeks resulted in a recurrence of decline of visual acuity in the left eye and retrobulbar pain in the right eye.

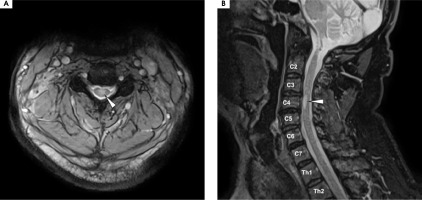

Figure V

Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine, T2 sequence. A) Axial projection: a centrally located hyperintensity is visible in the spine, affecting the gray matter and outlining the anterior and posterior horns, forming the “H sign.” B) A hyperintense lesion is seen occupying the C3-C4 space within the spinal cord. A diagnosis of short-segment transverse myelitis was made at that time

FOLLOW-UP AFTER PROLONGED IVIG THERAPY: CLINICAL AND RADIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT, 2024

At the most recent visit in late 2024, the patient was admitted for continued IVIG therapy. On admission, he was in good general condition, without abnormalities in the physical examination and no clinical signs of infection. No new symptoms or treatment complaints were reported by the patient. Neurological examination confirmed right eye blindness (LP) and impaired visual acuity with a limited field of vision in the left eye (VAS 20/25), with central vision preserved. Spastically increased muscle tone was observed in the right lower limb. Tendon reflexes were diminished in both upper limbs and slightly elevated, symmetrically, in the lower limbs, without signs of pathology. No signs of ataxia, sensory disturbances, or paresis were present. The latest follow-up brain MRI with gadolinium enhancement showed minimal progression of lesions, with no new lesions compared to previous follow-up studies (for axial projection, see Figure VI; for temporal sagittal projection, see Supplementary Figure I).

A routine laboratory check-up was performed, including MOG-IgG testing. Serum MOG-IgG was at borderline negative levels, with a titer of 1 : 10. No significant deviations were observed in the laboratory tests. Based on the core demyelinating event at onset, repeated positive serum MOG-IgG values in the FCBA test, and the fulfillment of additional supporting features according to the 2023 International MOGAD Panel proposed criteria, the diagnosis of late-onset MOGAD was upheld [5]. The patient received 120 g of IVIG during hospitalization, without adverse effects, and was discharged in stable condition. The next IVIG infusion was scheduled for 4 weeks later.

Figure VI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast from the follow-up visit in December 2024; axial projection, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence. Slices in a cranio-caudal sequence. Compared to the previous follow-up scans shown in Figure II, the scan revealed minimal evolution of supratentorial hyperintensities, which persisted despite minimal clinical symptoms and a satisfactory response to maintenance treatment. No new hyperintensities were observed compared to the previous follow-up MRI from the year prior. Similarly to previous studies, no contrast enhancement or diffusion restriction of the hyperintensities was noted

COMMENT AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Advances and limitations in understanding late-onset MOGAD: diagnostic criteria, research gaps and epidemiological challenges

In recent years, MOGAD has become a subject of extensive clinical interest and research focus. Advances in the field have led to the development of the first internationally recognized diagnostic criteria, with their high sensitivity and specificity confirmed in validation studies [2, 7-9]. Additionally, substantial progress has been made in understanding the disease’s pathomechanisms, as well as its distinct clinical and demographic characteristics. Despite recent advancements, MOGAD with onset in older individuals remains an underrecognized clinical entity with limited research focus and scarce literature. To date, only a small number of case reports and retrospective studies have examined MOGAD in patients over 50 years of age (Supplementary Table S1). One of the primary challenges in research on LO-MOGAD arises from the novelty of the subject, limited awareness of the issue, and the lack of large-scale epidemiological studies. An additional complicating factor is the historical absence of widely accepted and standardized diagnostic criteria. Prior to the introduction of the 2023 MOGAD panel’s diagnostic criteria [2], earlier studies often employed heterogeneous diagnostic approaches, heavily relying on differential diagnoses and serological testing. This frequently led to the misclassification of LO-MOGAD cases as NMOSD with MOG-IgG positivity, contributing to wide discrepancies in reported data and complicating the interpretation of research findings.

A 2023 study by Hor and Fujihara [3], which reviewed nationwide epidemiological data from several countries, established the mean age of MOGAD onset at approximately 28-30 years. Given the recent epidemiological shift toward a later age of onset and the increasing number of late-onset cases in MS studies, it is expected that both the age of onset and the overall prevalence of late-onset forms of other autoimmune demyelinating disorders, including NMOSD and MOGAD, will continue to rise [10-13]. This increase, like that observed in MS, will likely be driven by the aging of the population, longer life expectancy, and improved access to diagnostic tools [10, 14]. As a result, greater attention should be given to LO-MOGAD, as its relevance in aging societies should be expected to grow, presenting new challenges for clinicians and healthcare systems. Like MS and NMOSD, in which age at onset has been shown to influence demographic, pathophysiological, clinical, prognostic, and treatment characteristics, recent studies on LO-MOGAD suggest that age plays a crucial role in shaping disease phenotype, clinical progression, and treatment response [5, 6].

Initial clinical presentation and disease course in late-onset MOGAD

In our case, the patient exhibited a subacute disease onset, which is consistent with findings in the literature, suggesting that subacute presentation is more common among individuals with LO-MOGAD. A 2024 study by Huang et al. [5] analyzed clinical and imaging features of PO-, AO-, and LO-MOGAD, reporting that subacute onset occurred significantly more frequently in LO-MOGAD, whereas acute onset was more typical among younger patients. Regarding disease course, our patients exhibited a monophasic pattern during long-follow up. This is in line with findings by Cobo-Calvo et al. [4] and Fan et al. [6], who reported that older MOGAD patients are more likely to experience a monophasic course and have a lower relapse risk compared to younger individuals. The initial clinical manifestation in our patient was bilateral optic neuritis, which has been variably reported in the literature. While some sources indicate that both unilateral and bilateral optic neuritis occur more frequently in LO-MOGAD, others, such as Huang et al. [5] and Zhang et al. [15], found no significant age-related differences in the frequency of optic neuritis. Case reports also reflect this variability: bilateral optic involvement as the initial presentation was described by Du et al. [16], Deschamps et al. [17], and Teru et al. [18], while unilateral optic neuritis was reported in the cases of Jeyanathan et al. [19] and Razali et al. [20]. In our patient transverse myelitis developed secondarily, following bilateral LEON. Unlike optic neuritis, isolated transverse myelitis appears to be equally distributed across all age groups, with no reported predisposition among older individuals [5, 6, 21]. Interestingly, myelitis, in our case, lacked characteristic MRI features of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. This is consistent with findings by Huang et al. [???4, 5], who reported that older patients more frequently present with short-segment transverse myelitis, a pattern also noted in the case described by Kim et al. [22].

Radiological findings and lesion evolution in late-onset MOGAD

In our patient the MRI scans showed multiple supratentorial white matter and periventricular lesions with a predisposition toward the posterior horns of the lateral ventricles. This pattern aligns with observations reported Huang et al. [5], who found that LO-MOGAD patients are significantly more likely to present with deep white matter and periventricular lesions compared to younger individuals. In contrast, basal ganglia, cerebellar, and thalamic lesions – commonly associated with PO-MOGAD – were absent in our case, reinforcing the age-related radiological divergence noted in the literature [5]. However, interpretation remains challenging, as older patients more frequently present with cardiovascular risk factors and microangiopathic abnormalities, making it difficult to distinguish whether white matter and periventricular lesions are primarily related to the disease process itself or influenced by age-related factors. Similar diagnostic difficulties have been reported in MS and NMOSD, in which white matter and periventricular lesions also increase with age, further obscuring the attribution of pathologies [12, 22-24].

Furthermore, the findings of brain MRI in MOGAD differ significantly from those observed in MS [25]. Typically, MOGAD is characterized by poorly demarcated, bilateral, and frequently large lesions affecting both white and grey matter, with a tendency to appear in infratentorial regions such as the cerebellar peduncles. Periventricular lesions and Dawson finger-type appearances, which are hallmark features of MS, are generally absent. Cortical and juxtacortical lesions, if present in MOGAD, tend to follow a mixed pattern rather than the sharply defined profiles seen in MS. Silent (asymptomatic) brain lesions, in the absence of relapses, are also rare in MOGAD, in contrast to MS, where they are common and often used to monitor subclinical disease activity. The imaging distinctions outlined herein serve to substantiate the diagnostic separation of MOGAD from MS, a separation that is consistent with the radiological features observed in the patient.

Notably, the lesions observed in our patient demonstrated significant persistence with minimal evolution from the time of initial clinical manifestation to the most recent follow-up scan. This contrasts with prior studies showing that more than half of MOGAD lesions are seen to have resolved completely on follow-up imaging, even without treatment [26-28]. However, such studies predominantly focus on pediatric and early adult populations with a relapsing disease course. Our case contributes a novel insight by highlighting lesion stability in an older individual with LO-MOGAD, where age-related factors, comorbidities, and radiological lag may play a significant role. Moreover, differences in imaging timelines between studies further complicate direct comparison. A recent study has linked persistent MRI lesions in MOGAD to greater parenchymal destruction, reduced remyelination capacity, and increased axonal loss [29, 30]. In the context of our patient’s condition, the lack of lesion resolution over time may reflect an age-related decline in remyelination, compounded by vascular comorbidities. This supports the hypothesis that lesion dynamics in LO-MOGAD may differ in meaningful ways from those observed in younger patients, suggesting that age-specific factors should be considered when evaluating lesion behavior in LO-MOGAD.

Cerebrospinal fluid findings and the role of oligoclonal bands in late-onset MOGAD

CSF examination in our patient did not reveal any pathological abnormalities, a finding consistent with reports from previous research [4, 16, 21]. Notably, previous studies have suggested that age at onset may be a significant factor contributing to the relative absence of pathological CSF findings. Parameters such as leukocyte count, IgG index, pleocytosis rate, and concentration of CSF protein have been shown to vary with age, with younger individuals more frequently exhibiting typical signs of an elevated inflammatory response in the CSF [4, 5, 21]. In our case, the absence of such changes further supports these observations and may reflect the age-associated immunological profile at disease onset. Several factors may account for these findings. Age-related immune differences, including immunosenescence and an altered immune response, may account for a significant portion of the variations observed [31]. Immunosenescence is a multifaceted process involving both innate and adaptive immune dysregulation, including a decline in T-cell diversity, impaired B-cell function, and an elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine profile [31, 32]. These changes have contributed to the lack of overt inflammatory markers in the CSF of our patient, and more generally may influence both disease manifestation and treatment response in older individuals.

Another relevant factor may be disease phenotype and clinical course. Previous studies have shown that abnormal CSF parameters are more commonly associated with acute onset, initial myelitis phenotype and a relapsing disease course, whereas optic neuritis and a subacute onset with a monophasic course – features observed in our patient – are less frequently associated with such findings [33]. Elevated CSF/serum albumin, indicating BBB dysfunction and increased vascular permeability, was observed in our patient. While BBB dysfunction has been reported as a common feature in MOGAD patients [33], its presence in our case should be interpreted in the broader context of age-related microvascular pathology, comorbidities, and the general impact of aging on the integrity and function of the BBB [34, 35]. While some studies have reported the presence of CSF-specific OCBs in older patients, the findings remain inconsistent. No clear differences have been observed between different age-onset groups, with varying rates of the occurrence of OCBs reported [4-6]. Possible explanations for inconsistencies in the literature include small sample sizes and differences in disease phenotypes and courses. Notably, CSF-specific OCBs have been more commonly reported in MOGAD patients with an initial myelitis presentation, and in those with a relapsing course and higher recurrence rates [36, 37]. Additionally, the overall low frequency of OCBs in MOGAD, particularly in comparison to MS, may have influenced the variability of previous findings.

Applicability of the proposed 2023 MOGAD Panel criteria and serological testing in late-onset MOGAD

The proposed 2023 MOGAD Panel diagnostic criteria underscore serum MOG-IgG testing as a key element in establishing a MOGAD diagnosis [2]. In our case, testing with FCBA, conducted prior to the initiation of acute treatment following symptom onset, revealed low-positive values. Follow-up assessments demonstrated that fluctuations in MOG-IgG titers correlated with the clinical response to maintenance corticosteroid therapy and the recurrence of initial symptoms during tapering. While the 2023 diagnostic criteria state that low-positive MOG-IgG values require the presence of additional clinical or MRI features, previous studies have reported that older patients with MOGAD more frequently present with lower titer values than younger individuals, often persisting throughout the disease course despite treatment [2, 4, 5]. This pattern was also observed in our patients. A possible explanation may involve age-related immunological factors in older individuals. Immunosenescence may alter immune response by reducing the capacity of the B cell lineage for antibody production and by shifting the T-helper cell profile [31, 32]. These changes – resulting in an overall diminished ability to produce antibodies comparable to younger individuals, along with reduced systemic clearance of autoantibodies – may account for the persistence of MOG-IgG at low levels in older individuals without necessarily indicating an active disease process [38]. However, no significant correlation between MOG-IgG titer levels in LO-MOGAD and those in younger populations has been demonstrated to date. Several factors may account for this discrepancy, including small sample sizes, cohort heterogeneity, and variability in antibody testing methods and timing of the testing [39]. Other possible contributing factors include diagnostic delay (given that MOG-IgG levels decline over time), variation in disease phenotypes, differing treatment regimens, and inconsistent follow-up durations. Moreover, discrepancies in the application of the 2023 MOGAD panel diagnostic criteria between earlier and more recent studies may have influenced the comparability of results [9].

Assessment of progression of disability in late-onset MOGAD

In our case, disability severity was determined primarily on the basis of the VAS assessment. In some previous studies the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) has been used to measure disability progression in MOGAD [6, 21]. However, its applicability to NMOSD and MOGAD remains debated [40]. While the EDSS provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating overall neurological impairment and tracking changes over time, its emphasis on ambulatory and motor functions may limit its utility in capturing the full spectrum of disability in NMOSD and MOGAD [40]. The limitation is particularly relevant in MOGAD, where the EDSS may fail to objectively assess the functional consequences of visual impairment and cognitive dysfunction – both of which are critical in adult-onset cases. In our patient, this issue was clearly demonstrated: although other functional systems remained largely unaffected, the presence of profound visual impairment significantly contributed to overall disability yet could not be adequately measured using the EDSS. Additionally, most MOGAD patients experience substantial recovery from acute attacks, and an accumulation of inter-attack disability is not typically observed, unlike in MS. The EDSS also lacks sensitivity to factors such as pain and fatigue, which can have a considerable impact on quality of life in MOGAD patients [41]. To allow for a more accurate assessment of disability in these populations, alternative or complementary disability scales should be considered in future studies and clinical evaluation scales.

Treatment challenges in late-onset MOGAD

The treatment regimen in our case consisted of an acute first-presentation pulse of corticosteroid followed by maintenance therapy with an oCS, which was later replaced with IVIG therapy. While large-scale population studies comparing treatment response and adverse effects in older patients are currently limited, the first MOGAD-specific treatment protocols and healthcare medication programs for this population are still forthcoming. Our case illustrates the complexity of treating individuals with LO-MOGAD. Although a favorable response to initial corticosteroid therapy was observed, maintenance treatment could not be extended due to the presence of age-related comorbidities and the risk of potentially serious side effects. This outcome is in line with the findings of Huang et al. [5], where a lower proportion of LO-MOGAD patients received both acute and maintenance treatment, largely due to reduced corticosteroid use compared to younger individuals. Similarly, the study by Fan et al. [6] showed that LO-MOGAD patients tend to remain on maintenance therapy for a shorter duration than their younger counterparts primarily because of treatment-related side effects, with age-related comorbidities further limiting the feasibility of high-efficacy therapies. In our patient, this treatment course reflected those broader patterns, underscoring the practical limitations encountered in older populations. Despite the demonstrated efficacy of immunosuppressive agents in other autoimmune demyelinating disorders, particularly NMOSD, the evidence supporting their routine use in MOGAD remains limited and less definitive. In our case, IVIG was selected over more aggressive immunosuppressants, such as rituximab or tocilizumab, due to the patient’s age, multimorbidity, and overall safety profile. Tocilizumab is considered for cases that are refractory to other treatments. It is generally reserved for whom first-line therapies have failed due to their more aggressive immunosuppressive profile and potential safety concerns, particularly in older patients with comorbidities and polypharmacy, as is the case in this instance. From a pragmatic standpoint within Poland, access to rituximab and tocilizumab for off-label use in MOGAD can be constrained by regulatory and reimbursement restrictions, rendering them less viable options, particularly outside of clinical trial settings or in the absence of formal treatment guidelines specific to MOGAD. Comparable challenges have been described in other autoimmune demyelinating diseases [42, 43], emphasizing the need for future research focused on optimizing treatment strategies and individualizing care in LO-MOGAD.

Potential pathomechanisms underlying observed clinical differences in late-onset MOGAD

The underlying pathomechanisms contributing to the clinical differences between late-onset MOGAD and younger-onset cases remain an area of ongoing investigation. Potential contributing factors for the distinct clinical manifestations and comparatively less inflammatory disease course observed in older individuals may include age-related changes in the immune system. Immunosenescence, altered cytokine profiles, reduced antibody production capacity, and shifts in T and B cell lineages may collectively impair the body’s ability to trigger the active inflammation, resulting in a more smoldering disease process [30, 44, 45]. Additionally, the presence of age-related comorbidities, cardiovascular risk factors, BBB dysfunction, and reduced remyelination capacity may partly account for differences in imaging findings, functional outcomes, and treatment responses [15, 28]. Notably, several clinical and therapeutic patterns observed in older individuals with MOGAD have also been observed in late-onset NMOSD and MS [43, 46]. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that future research focusing specifically on older populations will provide deeper insights into LO-MOGAD, potentially elevating the understanding of this condition to the level currently achieved in late-onset NMOSD and MS.

LIMITATIONS

We have presented a single-case report, which inherently limits the generalizability of its findings. The patient’s complex medical history – including glaucoma and progressive visual impairment – may confound the interpretation of visual outcomes related to MOGAD, particularly in assessing the severity of optic neuritis and treatment response. Additionally, age-related comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes could have influenced both disease expression and therapeutic decisions. This case also illustrates the diagnostic complexity posed by overlapping ophthalmologic conditions, which may initially mask the inflammatory etiology of optic neuropathy and delay diagnosis. Moreover, limitations in the current literature including the scarcity of available studies on LO-MOGAD, small sample sizes, and heterogeneity in study designs further restrict comparison and generalization. The lack of internationally standardized laboratory testing methods, the recent introduction of the 2023 MOGAD diagnostic criteria, and the absence of widely accepted treatment protocols also complicate the interpretation of individual cases. The accompanying narrative literature review offers valuable context for understanding LO-MOGAD; however, as a non-systematic review it may be subject to selection bias. Finally, the relatively short follow-up period and the absence of standardized functional outcome measures further limit conclusions regarding long-term prognosis.

CONCLUSIONS

This case provides valuable insight into the clinical spectrum of LO-MOGAD, highlighting diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in older individuals with multimorbidity. The patient’s preexisting ophthalmologic conditions initially obscured the inflammatory nature of his visual deterioration, emphasizing the need to consider MOGAD even in patients with established structural eye disease. The disease course was characterized by subacute onset, bilateral optic neuritis, secondary short-segment transverse myelitis, and minimal radiological evolution, which is consistent with emerging observations in LO-MOGAD.

The positive response to corticosteroids and sustained stabilization under IVIG maintenance therapy support IVIG’s role as a viable long-term option in elderly patients where immunosuppression is limited by comorbidities. Radiological and serological findings, including persistent supratentorial lesions and low-titer MOG-IgG, may reflect underlying age-related immune alterations such as immunosenescence and impaired remyelination. Overall, this case reinforces the need for increased clinical awareness of LO-MOGAD and suggests that it represents a distinct phenotype requiring tailored diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.