INTRODUCTION

Human skin pigmentation and vitamin D have stirred substantial biological and medical research interest owing to their importance in human evolution. Human skin pigmentation is among the most visually distinctive traits, primarily determined by melanin. Vitamin D, commonly referred to as the “sunshine vitamin”, represents a unique element essential to human health [1]. Despite more than 100 years of research and numerous published articles, the cumulative impact of vitamin D and its derivatives on human health is not entirely known. Nevertheless, it is widely known that skin pigmentation and vitamin D share a direct yet complex evolutionary association. The current article is a comprehensive exploratory review aiming at decoding the molecular tapestry of two archaic biomolecules, melanin and vitamin D, using a variety of online databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed (Medline), Embase, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, JSTOR, and other. To find the essential information, a thorough search was conducted using the following keywords: skin, pigmentation, melanin, melanogenesis, synthesis, vitamin D deficiency, hypothesis, and evolution in all conceivable combinations. Figure 1 illustrates complete methodology of the literature search.

HUMAN SKIN PIGMENTATION: THE CANVAS OF EVOLUTION

Skin pigmentation is a crucial aspect of human evolution. The skin, the largest organ of the body, exhibits a polygenic trait with a complex genetic architecture. Geographical variation, harsh climatic conditions, complex genetic and biochemical compositions, and geographic isolation have all contributed to the diversity observed between and within human populations from an evolutionary perspective [2]. Skin pigmentation is a complex polygenic process involving intricate interactions, and the combined effects of admixture, natural selection, bottleneck events, and genetic drift are expected to be climacteric. Key alleles typically exhibit population-specific and pleiotropic effects, providing insight into the direction of evolutionary changes [2].

THE MAJESTIC MELANIN

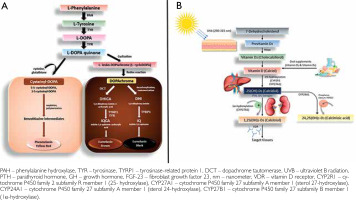

The primary biomolecule accountable for the pigmentation of human skin, melanin, has played an essential evolutionary function. Among all measurable environmental parameters, ultraviolet radiation (UVR) has the strongest evolutionary correlation with human skin pigmentation [3, 4]. Since the emergence of life on Earth approximately 3.9 billion years ago, numerous organisms have developed mechanisms to protect themselves from the harmful effects of excessive UVR exposure [5, 6]. In humans, melanin serves as the main UV-absorbing pigment (fig. 2 A), owing to its high refractive index and broad absorption spectrum [7]. Melanogenesis can also be stimulated by UV exposure, as occurs during skin tanning [8]. However, because pigmentation determines the degree to which UVR penetrates the skin, it also exerts a variety of downstream effects on human health [3, 4].

VITAMIN D: THE EVOLUTIONARY ELIXIR OF HEALTH

Vitamin D, the prototypical secosteroid hormone with an endocrine framework of activity, is synthesized sequentially in the skin, liver, and kidneys in humans. Vitamin D is known for its role in bone development, calcium absorption, and immune system functions. It also exerts non-classical activities in the immunological, muscular, reproductive, cardiovascular, and integumentary systems, as well as in cancer prevention [9–13]. Moreover, it is now widely acknowledged that vitamin D have imperative contribution in perpetuating the rectitude of the skin epithelium, digestive, respiratory, and urinary systems, as well as in improving the skin’s barrier function [14]. All stages of life can be affected by vitamin D deficiency, and many of these symptoms can increase the risk of mortality [15]. Vitamin D deficiency is linked to various diseases such as rickets, cancer, autoimmune and cardiovascular diseases, infections, and decreased fertility [16]. Vitamin D, synthesized in UVB-exposed skin, becomes less abundant during winter due to seasonal fluctuations and therefore must be obtained through diet or supplementation [17, 18]. Skin lightening may have evolved to prevent negative consequences of vitamin D insufficiency [3, 19].

CROSSLINK BETWEEN VITAMIN D AND MELANIN SYNTHESIS

Vitamin D is naturally synthesized by human skin when exposed to sunlight, starting when 7-dehydrocholesterol absorbs UVB (fig. 2 B). Factors like UVB dose, temperature, and lipid environment influence this process [20]. The melanin pigmentary system can affect vitamin D signalling due to the association between circulatory 25(OH)D and skin melanogenic mechanism, as seen in Caucasian populations [21, 22].

Human migration to northern latitudes may have led to lower UVR exposure, making it difficult for them to synthesize enough vitamin D. Hence, light-skinned individuals are in an advantageous position for this, as UVB permeates the skin more easily, increasing vitamin D production [23]. Dark-skinned early hominids’ ability to synthesize vitamin D was impaired due to scarce UVR, leading to rickets, pelvic deformities, and distorted leg bones, resulting in hindered hunting abilities [23]. Human dispersal across the globe affects vitamin D production [24], and skin pigmentation deteriorates as people migrate from lower latitudes to higher latitudes due to less sunlight. Thus, in competition with UV exposure, skin pigmentation is a major variable for directing the production of vitamin D [25].

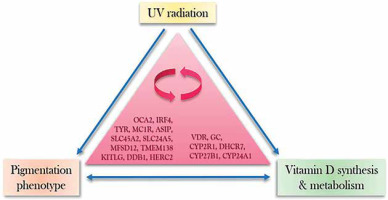

The preponderance of recent research has suggested an intricate interplay between vitamin D-related genes and genes responsible for skin colouration (fig. 3). Table 1 demonstrates the specific studies which discerned the significant association between skin pigmentation and vitamin D concentrations [26–35]. Although a study on 25(OH)D serum concentration in a Danish population found no correlation between variation in concentration and quantitative skin pigmentation, a significant association was observed with SNPs of skin pigmentation genes (ASIP, SLC24A4, SLC45A2, and MIR196A29) and other influential factors [36]. Another study on vitamin D-associated SNPs in European, East Asian, and Sub-Saharan African populations found population-specific patterns with genetic differences, suggesting potential patterns in vitamin D SNPs [37]. The study suggests these SNPs are linked to skin pigmentation evolution, similar to UVB radiation-regulated geographic selection. However, a Genome-Wide Association Studies among African Americans found no link between serum 25(OH)D concentration and melanin index, but a strong correlation was found between variants of three skin pigmentation genes (SLC24A5, SLC45A2 and OCA2) and severe vitamin D deficiency [38].

Figure 3

Hypothetical model of UVR-induced co-adaptation of pigmentation phenotypes and vitamin D synthesis, along with the associated gene interactions

Table 1

Articles on the significant association of quantitative skin pigmentation (melanin index) and vitamin D

| Conclusion of the study | Reference |

|---|---|

| Participants with high skin reflectance and high sun exposure had a small risk of vitamin D deficiency, meanwhile those with low skin reflectance and low sun exposure are likely to have a greater risk. | Hall et al. (2010) [26] |

| Prediction models with independent variables, such as age, sex, BMI, skin type, UV season, erythemal zone, total dietary vitamin D intake, and sun exposure factor explained 31% of the variance of s25(OH)D levels in white and 22% of the variance in black populations, respectively. | Chan et al. (2010) [27] |

| Sunlight-exposure recommendations are inappropriate for individuals of South Asian ethnicity living at UK latitudes, as skin pigmentation has a profound effect on the vitamin D response to sunlight exposure. | Farrar et al. (2011) [28] |

| Factors of vitamin D supplementation and sun exposure were significant in maintaining vitamin D levels in both populations. | Murphy et al. (2012) [29] |

| Ethnicity and constitutive skin pigmentation were associated with serum vitamin D levels. | Au et al. (2014) [30] |

| Infants who received the recommended ≥10 μg/day vitamin D supplements had significantly higher serum 25(OH)D levels and were largely protected against vitamin D deficiency and rickets, regardless of maternal vitamin D status, skin tone, season or ethicity. | Green et al. (2015) [31] |

| The vitamin D intake was needed to maintain serum 25(OH)D concentrations in 90% of the children, and pubertal status was a significant predictor of 25(OH)D concentrations after adjustment for total vitamin D intake. | Rajakumar et al. (2016) [32] |

| Children with white or black-pigmented skin both required vitamin D intake to maintain 25(OH)D concentrations. | Öhlund et al. (2017) [33] |

| Melanin inhibits the production of vitamin D. | Young et al. (2020) [34] |

| A higher melanin index was significantly associated with lower vitamin D levels only in boys measured in autumn, but not in spring. However, no significant differences in vitamin D concentrations or skin pigmentation were observed between boys and girls. | Iliescu et al. (2022) [35] |

THE EVOLUTIONARY COMPULSION

Murray’s original hypothesis stated that humans could only have survived in northern latitudes by developing depigmented skin, which allowed the limited UVB radiation available in those regions to penetrate the uppermost layers of skin and trigger the conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to vitamin D3 [39]. Loomis supported the hypothesis that selection favours dark skin near the equator to impede vitamin D overabundance, while light skin is preferred in distant territories to optimize vitamin D production [23]. Further explanations showed that spatial UV radiation affects vitamin D levels, leading to subsequent vitamin D deficiency in dark-skinned individuals [40]. However, Holick asserted that the rate-limiting nature of vitamin D production minimizes its potential adverse effects [41]. This led to the recognition that the regional distribution of skin pigmentation is influenced by factors beyond vitamin D levels alone.

THE BALANCING CONCOMITANT

Jablonski and Chaplin refined this conjecture by integrating it with another theory, forming what is now known as the vitamin D-folate hypothesis [3, 4, 25, 42, 43]. According to this hypothesis, the dual spectrum of human complexion evolved as a balancing mechanism to maintain stable levels of two essential vitamins: vitamin D and folate [3]. The differing sensitivities of these vitamins to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) suggest an evolutionary connection between them. On one hand, UVR stimulates cutaneous vitamin D synthesis; on the other, it can potentially degrade folate within the skin, either through direct absorption by folate molecules or through subsequent oxidation mediated by free radicals [44–49].

This hypothesis proposes that the evolutionary need to preserve folate levels from UVR-induced degradation initially drove the development of increased pigmentation in populations inhabiting high-UVR regions. In essence, the global distribution of human skin pigmentation represents an adaptive compromise: skin must be sufficiently dark in regions of intense UVR to prevent sunburn and folate photolysis, yet light enough in areas of low UVR to allow adequate vitamin D synthesis. More recently, Tiosano et al. provided genetic support for this hypothesis, demonstrating multilocus correlated adaptation between skin pigmentation genes and vitamin D receptor (VDR) genes, both exhibiting clear latitudinal clines [50]. Given the previously established epistatic interactions between VDR and pigmentation genes, this phenomenon is thought to result from parallel selective pressures and coadaptation driven by shared environmental factors [51].

ACCOUNT OF ADAPTABILITY

Since humans dispersed from Africa, their skin has evolved through genetic orchestration, resulting in variations in pigmentation. This is believed to be due to natural selection, which allows humans to adapt to different UVR situations. Humans did not immediately develop depigmented skin after migrating to higher latitudes. It took thousands of years for natural selection to act upon specific polymorphisms in pigmentation genes, driving the gradual transition from the ancestral dark-pigmented African condition, where humans had their evolutionary origin, to lighter pigmentation in higher latitudes. This change occurred under the selective pressures of diverse environmental factors, particularly varying UV radiation levels, as well as cultural influences. Although recent discoveries complicate any facile hypothesis, evidence suggests that a selective sweep of KITLG occurred approximately 30,000 years ago and was shared by both Europeans and East Asians. Another sweep involving three genes TYRP1, SLC24A5, and SLC45A2 took place between 11,000 and 19,000 years ago, leading to the fixation of European-specific alleles following multiple waves of human dispersal into Europe [52]. Further research on European skin pigmentation over the past 5,000 years, focusing on three additional pigmentary genes (TYR, SLC45A2, and HERC2), indicates that the process of depigmentation was spurred by a limited number of gene variants associated with modern phenotypic diversity [53].

TRANSITION, MIGRATION AND SUSTENANCE

After the Pleistocene climatic improvement, steppe grasslands in Eurasia expanded, leading to a rapid increase in human population. Agriculturists began migrating into southern and central Europe, displacing previous hunter-gatherer groups [54–56]. This transition from an animal-rich diet to carbohydrates led to immense selection pressure for the development of pale skin, potentially causing vitamin deficiency-related illnesses. Depigmentation of the skin, facilitating more cutaneous production of vitamin D, may have become a crucial fitness-increasing trait [57]. Recent archaeogenomic data on skin lightening in the European population reveals evidence of this change in dietary practices and the advent of agriculture [58–62]. Analyses of over thousand ancient West Eurasian genomes reveal that changes in the frequency of a few genes led to the development of light skin. Current research suggests that the most operative depigmentation variant of SLC24A5 (rs2675345) was brought into Western Europe by Anatolian agriculturalist admixture followed by positive selection [63]. Contemporary Arctic Native people, like Innuits, have a dark complexion, attributed to their marine diet high in vitamin D [2]. Meanwhile, nitrogen and carbon isotope research on hunter-gatherers in northern and western Scandinavia indicated that, despite eating a lot of seafood, they also had pale skin [64]. Early humans may have initially been able to preserve their ancestral pigmentation variant due to coastal dispersal, allowing the decreased level of vitamin D in the skin due to high melanin content [65–68]. Evidence from the genomes of Mesolithic inhabitants in Cheddar Gorge in Somerset, England and La Braña-Arintero site in Leόn, Spain supports this [61, 68].

THE HYPOTHESES CONUNDRUM

However, recent research challenges the long-standing consensus that dietary vitamin D deficiency facilitated the evolution of light skin color in the northern latitudes of Europe. Recent studies on archaeogenomic data and allele frequency for the genes that control vitamin D signalling, metabolism, and transportation from populations in Europe that date back to 10,000 years revealed that variations in the frequency of genes associated with vitamin D yielded an additional mechanism for adapting to the solar spectrum at northern latitudes [69]. As prevention from vitamin D deficiency ancestral Europeans grew to be more sensitive towards vitamin D3 and its metabolites rather than developing depigmented skin [69]. It is unlikely that depigmentation is caused only by the necessity of effective vitamin D production. The metabolic conservation hypothesis is a different conjecture conferred to justify subsequent depigmentation [70].

CONCLUSIONS

Vitamin D is crucial for the proper functioning of the immune, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems, and for calcium absorption and bone density. In contrast, melanin acts as a photoprotective barrier shielding the skin from harmful UVR. The roles of vitamin D synthesis and the human melanin pigmentary system have been intricately intertwined throughout human evolution, shaping the evolution of skin color. Studies indicate that the dispersal of modern humans across varying latitudes accelerated the emergence of diverse pigmentation phenotypes with distinct genetic architectures. Environmental and cultural factors, together with natural selection, have further influenced the evolution of skin complexion. Skin pigmentation plays a pivotal role in regulating vitamin D synthesis due to the biochemical interaction between melanin and 7-dehydrocholesterol. The recent advances in ancient DNA research offer the potential to bridge the gap between past and present, providing deeper insight into the complex and significant relationship between the ancient biomolecules melanin and vitamin D. This relationship can be explored through variations in historical UV exposure, shifts in dietary patterns, and other environmental factors that have shaped the evolutionary trajectory of human skin color.