INTRODUCTION

Substance use among adolescents is a pressing public health issue worldwide, often beginning during the teenage years in which the brain is still undergoing critical developmental processes [1]. Alcohol remains the most commonly consumed psychoactive substance among youth globally; over one-quarter of 15-19-year-olds – approximately 155 million adolescents – are classified as current drinkers [2]. Although less prevalent than alcohol, the use of illicit drugs among adolescents is still a significant concern. Cannabis is the most widely used illicit substance in this age group [2]. Recent estimates suggest that approximately 5.3% of adolescents aged 15-16 globally – roughly 13.5 million individuals – used cannabis in the past year [2]. Prevalence rates vary considerably by region: annual cannabis use among mid-adolescents is below 3% in parts of Asia but exceeds 17% in Oceania. In most regions, between 5% and 13% of adolescents report cannabis use – these figures often surpass those observed in the adult population [2]. In Europe, epidemiological surveys reveal that while the use of alcohol and tobacco among teenagers has declined in recent years, illicit drug use remains a persistent issue [3]. According to data from the 2019 European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD), approximately one in six European students aged 15-16 reported having used an illicit drug at least once in their lifetime [3]. National lifetime prevalence rates range from around 4% to 29%, reflecting considerable regional variation [3]. Cannabis remains the most commonly used illicit substance among European adolescents, with an average of 16% having tried it and approximately 7% reporting use in the past month [3]. Alarmingly, a notable minority begin to use cannabis at a very young age – roughly 2-3% of 15-16-year-olds in Europe reported first use at age 13 or younger [3]. Overall, trends in adolescent drug use across Europe have remained relatively stable over the past decade; ESPAD data indicate a slight decline in lifetime illicit drug use since 2011 and a plateau in cannabis use following previous increases [3].

Within Europe, countries in Southeastern Europe (the Balkans) have historically reported lower rates of adolescent drug use compared to the broader European average. However, recent data indicate an upward trend. In Albania, for instance, the ESPAD survey found that only 7% of 15-16-year-old students had ever used cannabis in 2015 – less than half the ESPAD average of 16% [4]. Nevertheless, this figure represents an increase on previous years: the proportion of Albanian adolescents reporting any illicit drug use rose from 8% in 2011 to 10% in 2015, with cannabis use increasing from 4% to 7% over the same period [4]. Similar trends are evident in neighboring countries. A school-based study conducted in Kosovo reported that by late adolescence (ages 17-19), approximately 17% of boys and 9% of girls had used an illicit substance at least once [5]. These findings suggest that while adolescent drug experimentation in the Balkans remains relatively lower than in Western Europe, it is an escalating trend. Moreover, there are indications that the age of first use is decreasing, likely due to the greater availability and accessibility of cannabis and other substances, reflecting regional apprehension that adolescents are increasingly beginning to experiment at younger ages [6].

Beginning substance use during adolescence is associated with a wide range of negative mental health outcomes. Adolescence is a critical period of neurodevelopment and psychosocial maturation, and exposure to drugs during this sensitive window can disrupt typical brain- and emotional development [1]. A growing body of research consistently links early substance use to an increased risk of psychiatric disorders and psychosocial difficulties. Adolescents who use drugs are more likely to experience symptoms of depression, apathy, and social withdrawal, and they exhibit a higher prevalence of behavioral disturbances. Those who engage in persistent drug or alcohol misuse are particularly vulnerable to developing mood disorders, conduct problems, personality disorders, and suicidal ideation or attempts [7].

Evidence from longitudinal studies indicates that early substance use – particularly of cannabis – can precede and potentially contribute to the development of psychiatric disorders. A 2019 meta-analysis of prospective studies found that adolescents who used cannabis had a significantly higher risk of developing major depression in young adulthood compared to non-users [8]. The same analysis also reported a 50% increased risk of suicidal ideation among individuals with a history of adolescent cannabis use [8]. In contrast, the association between adolescent cannabis use and anxiety disorders was weaker and not statistically significant in that meta-analysis; however, other studies still report high rates of comorbidity between substance use and symptoms of anxiety among the young [8]. Early initiation of the use of other substances, such as alcohol and stimulants, has likewise been linked to later-life depression and anxiety, likely due to their disruptive effects on the brain’s developing stress-response and reward systems [7]. Among the most well-documented mental health risks of adolescent drug use is an elevated likelihood of psychotic outcomes. Numerous studies have demonstrated that heavy or frequent cannabis use during adolescence can act as a trigger for psychosis in vulnerable individuals [9]. For example, a recent meta-review reported that adolescents who were frequent cannabis users had more than twice the odds of developing a psychotic disorder compared to peers who used cannabis infrequently or not at all [9]. This risk appears to be dose-dependent, with daily or heavy use – especially when initiated at a young age – conveying the highest likelihood of later psychosis [9].

Early substance use is also associated with the development of enduring personality and behavioural disorders. It frequently co-occurs with conduct disorder during adolescence, which may evolve into antisocial personality disorder in adulthood. Adolescents who misuse substances exhibit a higher prevalence of personality disorder traits compared to their non-using peers [7]. These findings underscore the substantial impact of adolescent substance abuse on mental health and overall development. The consequences extend beyond psychiatric disorders to include physical health complications, social difficulties, and legal issues; young individuals who use drugs are more likely to face academic failure, family disruption, medical problems, and involvement with the justice system [6]. Given the breadth and severity of these outcomes, there is a compelling need for early preventive strategies and timely intervention. International health authorities have emphasized the importance of comprehensive prevention programs targeting youth, as well as the availability of accessible, adolescent-friendly treatment services [6]. Early identification and intervention can reduce long-term harm and significantly improve life outcomes for young people [6].

This study, then, aims to identify and analyse the mental health and broader consequences of illicit substance use initiated during adolescence. The investigation focuses on psychiatric, physical, legal, and social outcomes associated with early-onset substance abuse.

Specific objectives:

to evaluate the impact of early substance use on the development of mental health disorders, including psychosis, mood disorders, and personality disorders;

to identify physical health complications and legal issues linked to adolescent substance abuse;

to examine the sociodemographic characteristics of individuals who began using illicit substances during adolescence.

Research question: What are the mental, physical, social, and legal consequences experienced by individuals who began their illicit substance use during adolescence?

Hypotheses:

Early substance abuse during adolescence is associated with a higher prevalence of mental health disorders in adulthood.

Male adolescents are more likely to engage in substance use than females.

Individuals who began using drugs before the age of 15 are more likely to develop severe psychiatric conditions or encounter legal problems.

METHODS

This retrospective descriptive study was based on statistical analysis and clinical records, covering a 10-year period from January 2014 to December 2024. The study included 312 patients who were hospitalized at the “Ali Mihali” Psychiatric Hospital in Vlora, Albania, and whose documented history of illicit substance use – beginning during adolescence – was verified through their clinical records from this hospital. Among these patients, 299 were male (96%) and 13 were female (4%). The age at first substance use was categorized into two groups: 12-14 (19.6%) and 15-18 years (80.4%). Medical data from other institutions, such as outpatient clinics or other hospitals, were not included in the study due to data access limitations and confidentiality protocols. Therefore, all clinical information was derived exclusively from the patient records of the “Ali Mihali” Psychiatric Hospital.

Eligibility criteria required that patients had complete and accessible psychiatric and medical records and that their substance use began during adolescence. All of the cases included met the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Patients were excluded if their substance use was limited to alcohol or if their initiation of substance use occurred after adolescence.

Instruments and assessment tools

Clinical data were extracted from hospital records and supplemented by structured psychiatric interviews. The evaluation of mood disorders and related functional impairments relied on well-established psychometric instruments that offer diagnostic precision and support individualized treatment planning.

The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), developed by Hamilton [10], is one of the most widely used clinician-administered tools. It evaluates the severity of depressive symptoms, including the emotional, cognitive, and somatic domains, and is frequently employed to monitor the progression of symptoms over time.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), developed by Beck et al. [11], is a self-report measure consisting of 21 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale. It captures a broad spectrum of symptoms of depression, such as hopelessness, fatigue, and appetite changes, and allows patients to express their subjective experiences of depression.

For broader screening purposes, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) – a self-administered tool derived from the PRIME-MD – was used to assess depressive, anxiety, and somatic symptoms. It aligns with DSM-IV criteria and is particularly effective for use in both clinical and epidemiological settings [12].

The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), developed by Young et al. [13], is considered the gold standard for evaluating symptoms of mania, particularly within bipolar spectrum disorders. This semi-structured clinician-administered scale assesses domains such as elevated mood, increased motor activity, and thought content.

Functional impairment was assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale from the DSM-IV-TR multiaxial system. Although diagnostic classification for inclusion in the study strictly followed DSM-5 criteria, some instruments historically associated with the DSM-IV-TR – such as the GAF scale – were still routinely used in clinical practice at the study site. Therefore, the GAF was applied for evaluating functional impairment, despite its removal from the DSM-5. The GAF provides a score from 0 to 100 to evaluate overall psychological, social, and occupational functioning and is frequently used to track changes over time or determine the need for support services [14].

Personality disorders were diagnosed on the basis of structured psychiatric evaluations conducted by attending psychiatrists during hospitalization, using the clinical criteria defined in the DSM-5. While no standalone psychometric instrument specific to personality disorders (e.g., SCID-5-PD or MMPI) was routinely employed, assessments included longitudinal clinical interviews, behavioural observation, and collateral information from family members or prior records when available. Distinctions were made between enduring personality traits and more pervasive structural personality pathology, though formal dimensional assessments were not part of the hospital’s standard diagnostic protocol.

Together, these tools formed a comprehensive assessment framework for diagnosing psychiatric conditions and planning evidence-based interventions in mental health care.

For the purposes of this study, each patient was treated as a single case based on their most clinically relevant or most recent hospitalization during the study period. While some patients had multiple admissions, these were not separately analysed. Diagnostic consistency was assessed across available admissions, and in most cases the primary diagnosis remained stable over time, with only minor changes in comorbidities or severity specifiers.

Data analysis

Descriptive data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel [15]. Results were presented using graphs and tables, categorized according to demographic and clinical variables.

RESULTS

In recent years, Albania has experienced a noticeable rise in adolescent drug use, accompanied by a decline in the average age of first-time users. According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) conducted in 2011 among high school students aged 14-18, 5.4% reported having experimented with cannabis, 4% with ecstasy, 1.6% with cocaine, and 1.4% with heroin [16]. These figures are presented in Table 1, which outlines the trends in illicit substance use among Albanian adolescents in 2011.

Table 1

Trends in the use of illicit substances among adolescents in Albania, Institute of Public Health data (16)

| Substance | Prevalence (ages 15-18) |

|---|---|

| Cannabis | 7.4% |

| Ecstasy | 4.2% |

| Cocaine | 3.2% |

| Heroin | 1.2% |

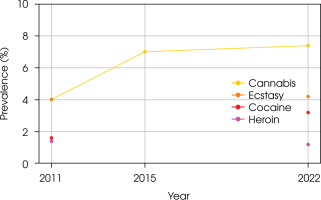

Additional data from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) conducted in 2011 and 2015 further support the observation of an upward trend in adolescent drug use [16]. ESPAD data show an increase in cannabis use from 4% in 2011 to 7% in 2015, while more recent data from the Institute of Public Health (2022) indicate a prevalence of 7.4% among adolescents aged 15-18 [3, 4, 16, 17]. These statistics collectively point to a gradual and sustained escalation in substance use among Albanian youth over the past decade. Figure I illustrates these trends among adolescents in Albania from 2011 to 2022.

Cannabis use, then, has increased steadily in Albania over the past decade, while the use of other substances such as cocaine and ecstasy had also risen noticeably by 2022 compared to 2011. As illustrated in Figure I, cannabis remains the most commonly used illicit substance, with its prevalence continuing to grow. The expanding use of cocaine and ecstasy among 15-18-year-olds signals a troubling trend toward the normalization of substance experimentation in this age group.

Globally, adolescent substance use follows similar upward patterns. According to data from the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics (NCDAS) [18]:

8.33% of Americans aged 12-17 reported using drugs in the past month;

among them, 83.88% had used marijuana;

46.6% of individuals aged 17-18 had tried illicit drugs at least once;

daily marijuana use was reported by 6.9% of 12th-grade students;

in a single year, 4,777 individuals aged 15-24 in the United States died from a drug overdose.

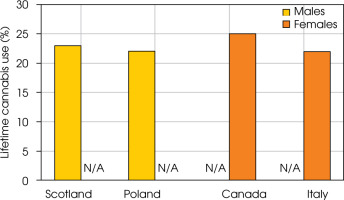

Gender differences in substance use are also evident. Generally, males tend to report higher rates of use than females. However, in some regions this gender gap is narrowing – or even reversing – over time. Figure II illustrates the rates of lifetime cannabis use at age 15 by gender in selected countries, including Scotland, Poland, Canada, and Italy.

These data highlight notable gender differences in adolescent cannabis use, with some countries reporting significantly higher prevalence among either males or females. Boys in Scotland and Poland exhibited the highest rates of lifetime cannabis use at age 15, with prevalence rates of 23% and 22%, respectively. In contrast, girls in Canada and Italy reported similarly elevated usage, at 25% and 22%, suggesting a narrowing or reversal of the traditional gender gap in these regions.

Global data reflect similar trends. According to the World Drug Report 2023, in 2021 [19]:

5.3% of adolescents aged 15-16 worldwide – approximately 13.5 million individuals – had used cannabis in the past year;

regional prevalence ranged from under 3% in Asia to over 17% in Oceania;

in most regions, cannabis use among adolescents exceeded that of the general population aged 15-64.

A retrospective analysis of psychiatric hospitalizations at the “Ali Mihali” Psychiatric Hospital in Vlora, Albania, identified 312 cases involving adolescent-onset substance abuse. This cohort revealed a pronounced gender imbalance: 96% of the patients were male (n = 299), while only 4% were female (n = 13). Analysis of the age of onset showed that:

19.6% of patients initiated substance use between the ages of 12 and 14;

80.4% began using drugs between the ages of 15 and 18.

Table 2 presents the detailed frequency distribution of age at onset among adolescents aged 12 to 18 years in the Vlora cohort.

Notably, a large proportion of hospitalized patients exhibited severe psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic episodes, suicidal ideation, and significant behavioural disorganization. These clinical manifestations reflect the profound mental health impact of early-onset substance abuse.

The textual and statistical analyses presented above highlight three key trends:

a rising prevalence of drug use among adolescents in Albania and globally;

persistent gender disparities, with substance use more common among boys – though usage among girls is steadily increasing in some regions;

a decreasing of age at the initiation of use, which substantially elevates the long-term risk of dependence and associated mental health complications.

Possible causes of substance use in Albania

An analysis of 312 patients hospitalized over a 10-year period at the “Ali Mihali” Psychiatric Hospital in Vlora reveals distinct socio-demographic patterns among individuals who began using illicit substances during adolescence.

As we have seen, a substantial majority of these individuals were male (96%), while only 4% were female. However, in recent years there has been a slight but noticeable increase in the number of female patients, suggesting an emerging trend that may require closer monitoring and gender-specific preventive strategies.

Regarding marital status, 78.8% of the patients were single, while 11.9% were married, 8.7% divorced, and 0.6% widowed. The high proportion of unmarried individuals suggests a pattern of social isolation or a lack of stable interpersonal relationships. Many patients reported living alone, and in several cases, they had been abandoned by partners or family members as a consequence of their substance use and its associated effects, including a deterioration in their mental health, school dropout, unemployment, and legal issues. These forms of social disconnection appear to exacerbate their vulnerability.

Table 2

Age onset patterns of substance use among adolescents in the Vlora cohort

| Age of onset | Patients, n | Prevalence rate, % |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 11 | 3.6 |

| 13 | 14 | 4.6 |

| 14 | 36 | 11.2 |

| 15 | 65 | 20.4 |

| 16 | 38 | 12.5 |

| 17 | 43 | 13.2 |

| 18 | 105 | 34.5 |

Educational background further reflects a profile of marginalization. Over half of the patients (51.6%) had completed only 8-9 years of schooling, followed by 35.3% who had completed secondary education. Just 9.3% had attained higher education, while 2.9% had only completed primary school, and 1% were illiterate. The data suggest that early school dropout was frequently associated with the onset of substance use. Many patients reported that their schools lacked adequate psychosocial support personnel, such as school psychologists or social workers. In cases where such staff were present, they were often disengaged or insufficiently responsive. Moreover, collaboration between schools, families, and local educational authorities was often weak or entirely absent. As a result, students exhibiting early signs of substance use were neither referred to appropriate treatment services nor supported through school-based rehabilitation programs.

The employment status of the patients further illustrates a troubling picture. A majority (60.9%) were unemployed, while 22.4% were classified as disabled – often as a result of chronic mental health conditions or deteriorating physical health. Only 16.7% of the patients had any form of employment. For many, severe psychiatric conditions such as psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, or cognitive impairments had led to long-term functional decline, rendering them unable to maintain stable jobs. Furthermore, institutional support appeared insufficient: local social services and employment agencies offered limited assistance, and few targeted programs existed to support the reintegration of individuals with a history of substance abuse and psychiatric illness into the workforce.

With respect to place of residence, 55.1% of patients came from urban areas, while 44.9% originated from rural zones. This distribution reflects broader demographic trends in Albania, particularly the internal migration from rural regions to urban peripheries in search of improved living conditions. However, many of these families settled in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods characterized by high unemployment, substandard housing, and limited access to health and social services. Adolescents raised in such environments were more likely to encounter psychosocial risk factors – including exposure to drugs, poor supervision, and reduced educational opportunities – that increase susceptibility to substance use.

Among the 312 patients hospitalized for substance-related psychiatric disorders, 45 individuals (14.4%) had documented involvement with the legal system. The most frequently reported offence was drug trafficking, accounting for 31.1% of these cases, highlighting a direct link between substance use and participation in the illegal drug trade. Domestic violence followed closely, representing 28.9% of offences – often as a consequence of relationship breakdowns and aggressive behaviors associated with substance use or co-occurring psychiatric symptoms. Theft was reported in 17.8% of cases, likely driven by financial hardship or the need to sustain drug dependence. An additional 22.2% of patients had committed other serious offenses, including assault, illegal possession of weapons, property damage, and, in rare cases, homicide.

These findings underscore the strong overlap between substance use disorders and antisocial or violent behavior, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary interventions that incorporate both psychological rehabilitation and social reintegration strategies.

A detailed review of clinical records revealed that the vast majority of patients (n = 245) had a history of cannabis use as their primary or sole substance, making it the most commonly abused drug in this population. However, poly-substance use was also evident in 56 patients (17.9%), with the most prevalent combination being cannabis and cocaine (24 cases). Notably, 30 patients reported the concurrent use of cannabis, cocaine, and heroin – an especially high-risk pattern typically associated with accelerated psychological decline and greater resistance to treatment. Smaller numbers reported exclusive use of cocaine (10 patients) or heroin (1 patient). These patterns suggest a dominant preference for cannabis – used either alone or in combination – but also reveal a growing trend of escalating drug experimentation among a subset of patients.

Psychiatric and somatic effects of hospital abuse in Albania

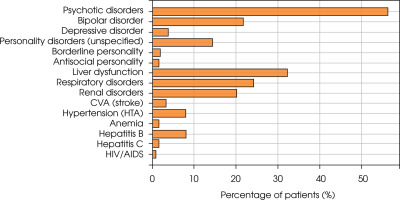

A significant proportion of adolescents hospitalized for substance use disorders presented with severe psychiatric conditions, often accompanied by comorbid physical illnesses. Among the psychiatric conditions, psychotic symptoms were the most prevalent, observed in 176 patients (56.4% of the cohort). These encompassed both acute substance-induced psychotic episodes and chronic psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. While substance use may serve as a triggering or aggravating factor in some cases, particularly among vulnerable individuals, it is not assumed to be the sole cause of these chronic conditions. Within the mood disorder spectrum, 68 individuals (21.8%) were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, while 12 patients (3.8%) met the criteria for major depressive disorder. These findings underscore the pronounced emotional instability and affective dysregulation associated with early and prolonged substance use.

Regarding personality disorders, 56 patients exhibited clinically significant maladaptive traits. Of these, 45 individuals (14.4%) were diagnosed with unspecified personality disorders, 6 (1.9%) with borderline personality disorder, and 5 (1.6%) with antisocial personality disorder. These patterns highlight the complex psychological profiles frequently observed in adolescents with histories of chronic substance use.

Physical health complications were also common. A total of 124 patients (39.7%) were diagnosed with one or more somatic illnesses. The most frequent condition was liver dysfunction, reported in 32.3% of patients with somatic diagnoses – likely attributable to substance toxicity or co-infections. Respiratory disorders were observed in 24.2% of cases, followed by renal dysfunction (20.2%), cerebrovascular events (3.2%), and hypertension (8.1%).

In addition, isolated cases of HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B and C, and anaemia were identified. The presence of both psychiatric and somatic comorbidities reflects the multisystemic burden of early-onset substance use, emphasizing the urgent need for integrated care models that address both mental and physical health.

Figure III illustrates the prevalence rates of the most common psychiatric and somatic conditions among adolescents hospitalized for substance abuse. As is shown, psychotic disorders and liver dysfunction were the most frequently occurring comorbidities.

Figure III

The prevalence rate of psychiatric and somatic comorbidities among adolescents with a medical history of substance abuse

Over the past decade, the “Ali Mihali” Psychiatric Hospital in Vlora has treated approximately 312 individuals who had a history of substance use beginning in adolescence and were subsequently diagnosed with various mental health disorders. While these cases show a temporal association, the study design does not allow for definitive conclusions regarding causality. Among them, 299 were male and 13 were female. Clinical records reveal that the age of onset for substance use has dropped as low as 12 years in some cases. While substance use remains significantly more prevalent among males, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of female patients in recent years.

Educational attainment was generally low among these individuals. The majority had completed only 8-9 years of schooling. School systems were often ill-equipped to intervene. As mentioned above, most institutions lacked specific programs to prevent school dropout or to identify and support students with substance use problems. Furthermore, family support was frequently absent or inadequate, and collaboration between educational institutions and families appeared limited.

In terms of marital status, most patients were single and lived alone, suggesting a pattern of social isolation. The majority originated from urban areas, a reflection of the already noted and ongoing internal migration from rural to urban regions in Albania over the past three decades. Many of these patients were unemployed and classified as disabled, receiving disability benefits due to chronic mental health conditions or serious physical illnesses. Public support services were largely insufficient, with minimal effort being made by local authorities to address employment and housing needs for this vulnerable population.

Substance use during adolescence is a well-established risk factor for the development of mental illness and addiction in adulthood. The most frequently diagnosed psychiatric disorders in this cohort included:

psychotic disorders, such as substance-induced psychosis, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder;

mood disorders, both unipolar and bipolar;

personality disorders, including unspecified, antisocial, and borderline subtypes.

In addition, many patients presented with co-occurring physical illnesses, the most common of which included liver dysfunction (elevated transaminases), hepatitis B or C, urinary tract infections, hypertension, cerebrovascular accidents, respiratory conditions (e.g., bronchitis), and anaemia. One patient was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS.

A total of 45 patients (14.4%) had documented legal issues. The offenses included drug trafficking, domestic violence, theft, physical assault, arson, property damage, and, in rare cases, homicide – indicating a significant overlap between substance abuse, psychiatric illness, and criminal behavior.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study clearly underscore the profound and multifaceted consequences of substance use initiated during adolescence, aligning with the global literature that identifies adolescence as a particularly vulnerable period for the onset of mental and behavioural disorders – and a critical window for preventive intervention [1, 8]. In the context of Albania, this study offers rare longitudinal insight into the psychiatric, physical, and social burdens experienced by individuals who began using illicit substances at a young age and were later hospitalized for associated mental health conditions.

A key observation was the notably early age of the beginning of use, which aligns with international concerns about the declining age of onset. This finding is consistent with international trends [2]. Early exposure to illicit substances in the environment significantly increases vulnerability to long-term psychiatric complications, most notably psychotic disorders – the most common diagnosis in the present sample. The predominance of psychotic disorders – previously detailed in the Results – reinforces their close association with early substance use [9].

In addition to psychotic disorders, a substantial proportion of patients were diagnosed with mood and personality disorders, highlighting the emotional and behavioural instability often linked to adolescent substance abuse. However, it must be noted that diagnoses of personality disorders in this study were made primarily through clinical evaluation without the use of structured psychometric instruments, which may limit diagnostic specificity. The observed traits may, in some cases, reflect emerging or situational maladaptive behaviors rather than fully developed personality pathology. In addition, it is important to note that emotional instability and affective disturbances may not merely result from substance abuse but can also precede and contribute to its development. This reciprocal interaction is well-documented, particularly in adolescents with underlying vulnerability to mood dysregulation, who may use substances as a form of maladaptive emotional self-regulation. Bipolar disorder, borderline personality traits, and antisocial behavior patterns were frequent, echoing existing evidence that substance use can both mask and exacerbate underlying psychopathologies [7]. Moreover, it is essential to acknowledge that certain maladaptive personality traits – such as impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, and conduct problems – may precede and predispose adolescents to substance use. These traits can serve as risk factors that heighten vulnerability to early experimentation and maladaptive coping behaviors. In turn, prolonged substance use may exacerbate or reinforce such traits, creating a reciprocal and self-perpetuating cycle. Recognizing this bidirectional relationship is crucial for developing more effective prevention and early intervention programs that target personality development and behavioural regulation during adolescence [20].

Moreover, the presence of co-occurring physical conditions such as liver dysfunction, respiratory illnesses, and cardiovascular complications reveals the systemic toxicity of prolonged drug use. The relatively high prevalence of infectious diseases – including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV – further points to engagement in risky behaviors such as needle sharing and unsafe sexual practices, which are frequently associated with polysubstance use [21]. These findings reinforce the necessity for integrated care models that address both the psychiatric and somatic dimensions of substance use disorders, particularly in recovery and rehabilitation settings.

From a socio-demographic perspective, the majority of patients were male (96%), unemployed, undereducated, and socially marginalized – a profile consistent with findings from other low- and middle-income countries [3]. However, the observed increase in substance use among adolescent females is a concerning development that underscores the need for gender-sensitive prevention and intervention strategies. This strong male predominance is consistent with findings across Europe and globally, where substance use – particularly involving cannabis, stimulants, and alcohol – remains more prevalent among adolescent boys. According to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), boys are more likely to engage in riskier and more frequent substance use, which may lead to earlier and more severe psychiatric complications requiring hospitalization. However, studies have also documented a narrowing gender gap in some countries, especially among girls who use prescription drugs or engage in polysubstance use. The low number of female patients in our cohort may reflect underdiagnosis, cultural stigma, or differences in help-seeking behavior, where girls with substance-related issues might remain in outpatient settings or receive family-based interventions rather than psychiatric hospitalization. These findings emphasize the need for gender-sensitive screening and support services that can identify at-risk girls earlier and prevent escalation to severe outcomes [22].

Gender-sensitive approaches are essential for effective prevention and intervention, especially as recent trends show a gradual increase in substance use among adolescent girls. Research indicates that girls may initiate drug use for different reasons than boys – often linked to experiences of trauma, anxiety, or peer pressure – and are more likely to internalize symptoms, leading to underdiagnosis or delayed treatment [23, 24]. Programs targeting young females should therefore incorporate components addressing emotional regulation, trauma-informed care, and social empowerment. Culturally sensitive and accessible support services must also be developed to overcome stigma and promote help-seeking behavior among adolescent girls.

Legal consequences were also a prominent feature within this cohort, with nearly 15% of patients having a documented history of involvement with the criminal justice system. The most common offences included drug trafficking, domestic violence, and theft. These findings align with global data highlighting the intersection between adolescent substance abuse and criminal behavior [7]. They emphasize the need for preventive justice initiatives, such as community-based policing and diversion programs, which aim to intervene early and reduce the risk of deepening marginalization through formal criminalization.

The study also reveals a systemic failure in early prevention by both educational institutions and families. The absence of school psychologists, weak referral systems, and poor collaboration between schools and families left many at-risk adolescents without access to critical support. These structural deficiencies underscore the need for public health policies that prioritize early identification and support within schools – such as implementing routine mental health screening, psychoeducation programs, and accessible referral pathways to specialized services. These measures may help redirect vulnerable youth away from trajectories that lead to hospitalization and long-term psychosocial harm.

While the data show a clear association between adolescent substance use and subsequent psychiatric diagnoses, these findings must be interpreted with caution. The retrospective nature of the study and the absence of data on confounding variables – such as family history of psychiatric illness, exposure to early trauma, or genetic predispositions – limit our ability to draw definitive causal conclusions. It is well-established that mood disorders such as bipolar disorder and major depression can arise from a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and environmental factors, including but not limited to substance use. Therefore, the role of early drug exposure should be viewed as one contributing factor among many. Future prospective studies incorporating multivariate analyses are necessary to disentangle these interrelated influences and to clarify the directionality and strength of these associations. Moreover, the relationship between substance use and psychiatric disorders is likely bidirectional. Emerging evidence suggests that pre-existing mental health conditions – such as anxiety, depression, or certain personality traits – can increase vulnerability to substance use during adolescence, often as a form of self-medication [25]. This is particularly relevant in cases where internalizing symptoms precede substance initiation, pointing to a complex interplay between emotional distress and maladaptive coping strategies. The self-medication hypothesis and related models underscore that psychiatric distress may not only result from substance use but also contribute to its onset and persistence. Therefore, interpreting the causal direction in this cohort requires caution, and future studies should incorporate baseline psychological assessments and longitudinal designs to disentangle these reciprocal influences. In addition, the absence of a control group – such as adolescents hospitalized for non-substance-related reasons or those without a history of substance use – limits the ability to draw firm conclusions regarding causality. As this is a retrospective descriptive study, the findings should be interpreted as associative rather than causative. Future research should include prospective and controlled designs to explore the directionality and specific contribution of substance use to psychiatric outcomes more precisely.

The predominance of cannabis use in this cohort – whether as a primary substance or as part of poly-drug use – mirrors patterns reported across Europe and North America [8]. Although cannabis is often perceived as a relatively harmless or “soft” drug, the findings of this study reinforce that its heavy use during adolescence is anything but benign. Cannabis use was frequently associated with psychotic symptoms and behavioural dysregulation, particularly when used in combination with cocaine or heroin.

Based on the findings of this study and existing international evidence, several clinical and public health recommendations can be proposed to prevent early substance initiation and reduce long-term psychiatric and social consequences. School-based prevention programs, such as the LifeSkills Training (LST) model or Unplugged, have been shown to reduce early substance use by strengthening adolescents’ psychosocial skills, drug refusal abilities, and risk perception [26]. Additionally, integrating trained mental health professionals into school environments can facilitate early detection of at-risk youth and timely referrals to psychiatric services. Community-level interventions – such as youth centres offering structured recreational, educational, and counselling services – can provide protective social networks and alternative coping strategies. Family-focused programs, including parent training and family therapy (e.g., Multidimensional Family Therapy, Brief Strategic Family Therapy), have demonstrated effectiveness in improving parenting practices, strengthening family communication, and reducing adolescent risk behaviors [27, 28]. In Albania, implementing these evidence-based models through multisectoral cooperation (health, education, and social protection sectors) may significantly improve prevention and early intervention outcomes.

Overall, the results of this study support the initial hypotheses. Early-onset substance abuse is strongly associated with a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders, increased exposure to social and legal adversity, and disproportionately affects adolescents from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. These findings reinforce the urgency of early intervention, cross-sectoral collaboration, and sustained investment in adolescent mental health and substance use prevention. Targeted efforts are especially needed for at-risk youth in vulnerable communities, where the intersection of substance abuse, mental illness, and systemic neglect can have lifelong consequences.

These findings must also be understood in the context of Albania’s recent socioeconomic transformations. Over the past three decades, the country has experienced significant internal migration, with many families relocating from rural regions to urban peripheries in search of better economic opportunities. However, this movement has often led to increased marginalization, with limited access to education, employment, and healthcare services in rapidly expanding urban zones. Adolescents growing up in such transitional environments may face heightened psychosocial stress, disrupted social networks, and reduced protective oversight, all of which can elevate the risk of early substance initiation and mental health deterioration. Moreover, disparities in service availability between urban and rural areas may influence patterns of hospitalization, diagnosis, and treatment-seeking behaviour.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides valuable insight into the long-term consequences of adolescent substance abuse, based on a decade of clinical data from the “Ali Mihali” Psychiatric Hospital in Vlora. The findings demonstrate a strong association between early drug use – particularly cannabis – and the presence of serious psychiatric disorders, co-occurring medical diseases, and legal complications. While substance abuse appears to play a significant contributory role, these outcomes are likely shaped by a broader set of individual and social factors.

Most of the affected individuals came from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, characterized by low educational attainment, unemployment, and social isolation. The high prevalence of psychotic disorders, along with substantial rates of mood and personality disorders, underscores the urgent need for early identification and treatment of substance use among adolescents. In addition, the presence of medical comorbidities and the significant incidence of criminal behavior further reflect the multidimensional nature of the problem – one that intersects public safety, education, social services, and mental health care.

Given the complexity and severity of the outcomes associated with adolescent substance use, it is imperative that Albania – and other countries facing similar challenges – adopt comprehensive, multisectoral strategies. These should include strengthening school-based mental health services, developing effective prevention programs within the educational system, and promoting family education and early intervention efforts to identify and address substance use problems as they emerge. Improving access to adolescent-friendly treatment services is essential to ensure that young people receive timely and appropriate care.

Furthermore, sustainable recovery must be supported by social reintegration measures, including access to education, vocational training, and employment opportunities for individuals with substance use disorders. Addressing these issues holistically may significantly reduce the long-term burden of drug abuse on individuals, families, and society at large.

In this context, the present study serves not only as a call to action but also as a foundation for future research and policy development focused on adolescent mental health and substance abuse prevention in Albania and the broader Balkan region.