INTRODUCTION

“It is important not only what disease the person has, but also what kind of person has the disease.”

Hippocrates

At the end of December 2019, a new species of coronavirus was publicly reported. At the time, this virus was the cause of an increasing number of pneumonia cases in the Chinese city of Wuhan. The etiological agent was the virus responsible for severe acute respiratory syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. This article refers to the disease named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [2]. COVID-19 quickly turned into a rapidly spreading infection in the Wuhan region and subsequently throughout China [1, 2]. From China, where SARS initially caused an endemic outbreak, the virus gradually spread across the globe, leading to a worldwide epidemic [3]. The exponential increase in infections soon overwhelmed healthcare systems worldwide [4]. In early March 2020, the outbreak was officially characterized as a pandemic (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020) [5]. As a result, the WHO highlighted the excessive burden placed on healthcare workers (physicians, psychologists, and others) and called for interventions to meet the urgent needs of and prevent serious psychophysical consequences for the global population [6].

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic was the first of such magnitude in the 21st century [1, 6]. It posed a tremendous medical, organizational, and social challenge, dividing societies into at least a few groups, including two dominant ones: those who believed the pandemic was real and consequently adhered to all restrictions and regulations, and those in denial, opposing the rules of general quarantine. Nevertheless, at least in the early phase, everyone tried to prepare for it as best as they could [7].

Technological and scientific advancements have led researchers in psychological and medical sciences (especially psychiatry) to pay increasingly less attention to the spiritual dimension of human existence [8]. However, according to the WHO’s definition of health, achieving complete health also involves maintaining spiritual well-being [9]. Many physicians, including psychiatrists and psychologists, base their diagnostic and therapeutic procedures on a holistic approach that takes into account the spiritual needs of patients, which appears justified given the current state of knowledge [10]. Such a comprehensive approach helps maintain balance in the human being, leading to physical, emotional, social, and spiritual harmony [11, 12]. Psychiatrist and Nazi concentration camp survivor Viktor Frankl wrote that “man is not destroyed by suffering; he is destroyed by suffering without meaning” [13]. Philosophers and ethicists concerned with both physical and mental health remind us that religion and spirituality constitute, for many, a foundation for meaning and purpose in life [14-17]. Regaining psychophysical balance – including through faith – may play a key role in the subjective sense of health improvement [18, 19]. Such a restoration of balance can involve reaching an internal acceptance of illness and discovering its meaning. In its essence, this process has a spiritual dimension, which can also be applied to experiences related to the COVID-19 pandemic [20].

Based on the authors’ own observations, spirituality, religion, and the accompanying life philosophy of individuals seemed to have a significant influence on attitudes toward the pandemic (e.g., quarantine regulations, preventive measures, and later, vaccination against SARS-CoV-2). This assumption served as the rationale for initiating the present investigation and main motivation for conducting the survey. The topic addresses a significant gap in the literature and retains its relevance in the current post-pandemic era.. The main aim of the study was to investigate whether religiosity and anxiety levels could differentiate health-promoting attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemic and coping strategies.

The primary aim of this study was to assess the relationship between religiosity and health-promoting attitudes in the context of preventing COVID-19 infections, complying with sanitary restrictions, and having a positive attitude toward vaccination. The study also aimed to analyze whether anxiety related to the pandemic influenced these attitudes among religious and non-religious individuals. Throughout the article, the terms “believers” and “religious individuals” are used interchangeably, as are “non-believers” and “non-religious individuals”. This stylistic variation reflects the same classification made by participants, based on their declared religiosity or lack thereof. Finally, the research sought to evaluate preferences regarding coping strategies in the face of the coronavirus threat and to determine whether these preferences varied depending on the level of anxiety experienced.

METHODS

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Polish-language version of Statistica 13.1, and charts were created with Microsoft Excel (Office 365). The choice of statistical methods was tailored to the type of data required for the analysis. In the initial phase, frequency statistics were used to describe the study sample, taking into account sociodemographic characteristics such as gender, place of residence, and age of respondents who believed and did not believe in God. To address the research objectives, more advanced analytical methods were applied. Due to the nominal nature of the dependent variables, Pearson’s χ2 test of independence was used to examine relationships between variables. For quantitative variables, differences between means were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The α confidence level was set at 0.05. Accordingly, results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, and results at p < 0.1 were interpreted as showing a statistical trend.

Research instruments

The study employed the Mini-COPE questionnaire [21], a shortened version of the COPE inventory used to assess stress-coping strategies. In the Polish adaptation [22] seven factors were identified: Active Coping (including strategies such as Active Coping, Planning, Positive Reframing), Helplessness (Substance Use, Behavioral Disengagement, Self-Blame), Seeking Support (Emotional Support, Instrumental Support), Avoidant Behaviors (Distraction, Denial, Venting), Turning to Religion, Acceptance, and Sense of Humor [22].

The Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) [23] measures levels of anxiety and stress induced by the pandemic. The tool includes 7 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 – “Strongly disagree” to 5 – “Strongly agree”) and demonstrates high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.84). It is used in clinical practice to assess mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression, and to tailor psychological support [24].

Additionally, an original questionnaire was used, containing questions related to emotional problems, states of depression and anxiety, access to psychological support, the impact of quarantine and pandemic restrictions, the importance of faith, contact with God, and experiences of healing miracles.

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants by degree of religiosity

The study was conducted online using the original questionnaire, the FCV-19S Scale, and the Mini-COPE. Although the original questionnaire was not formally validated, its questions were reviewed by a team of experts. The study participants were recruited via social media platforms, primarily Facebook and Instagram. Data collection took place from March to May 2021. Recruitment was open and voluntary, with the survey link distributed online. The study was exploratory in nature, and the respondents constituted a non-representative sample recruited using the snowball sampling method.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the survey sample

The study involved 700 participants, of whom 63.6% identified as religious and 36.4% as non-religious. Complete data from the survey and questionnaires were obtained from 289 individuals, which formed the basis for further analysis. Among the religious respondents, women constituted the majority (66.1%), while in the non-religious group the gender distribution was more balanced (women – 51.8%, men – 48.2%). In both groups, the majority of participants were young adults. Within the group of religious individuals, most declared themselves as Catholic (49.7%), followed by Orthodox Christians (35.3%). Protestants accounted for 2.0%, and 13.0% identified with other denominations or religious groups (e.g., Jehovah’s Witnesses, Pastafarians, followers of Slavic Native Faith). A majority of believers (73.0%) believed in the possibility of divine miracles, and 28.5% reported having experienced healing after prayer. However, more than half (52.6%) stated they were not aware of such healing, and 18.9% declared they had not experienced a miracle. Faith was seen as a source of inner peace by 76.4% of believers, while 13.0% did not perceive such an effect, and 10.6% had no opinion on the matter. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 58.7% of religious participants stated that their faith helped alleviate fear, while 22.9% reported no such effect. Prayer was used as a method for coping with stress by 70.1% of religious respondents, while 16.2% stated it did not help reduce stress. The pandemic was viewed as a test of faith by 29.0% of religious participants, whereas 49.7% rejected this interpretation, and 21.1% had no opinion. Only 13.0% believed the pandemic was a punishment from God for humanity’s sins, while 66.8% disagreed. Spiritual support from clergy during the pandemic was sought by 40.7% of believers, whereas the majority (59.3%) did not use such assistance. The results indicate considerable diversity in attitudes toward faith and its role in everyday life as well as in the context of the pandemic. Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1.

Achieving research objectives – hypothesis verification

Religiosity and health attitudes: compliance with preventive measures, opinions on restrictions, and COVID-19 vaccination – key associations

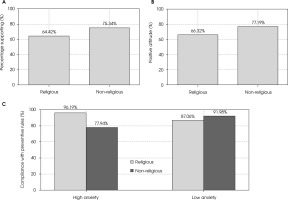

The relationship between religiosity or the absence thereof and adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures was examined. The χ2 test of independence showed no statistically significant differences between religious individuals (89.21% reported compliance) and non-religious individuals (88.24% reported compliance). This indicates that religiosity did not influence the level of adherence to preventive measures. Regarding pandemic-related restrictions in places of worship, non-religious participants were more likely to express positive attitudes (75.34%) compared to religious participants (64.42%). Conversely, a higher proportion of religious individuals expressed negative opinions toward these restrictions (35.58%) than non-religious individuals (24.66%) (χ² = 7.79, df = 1, p = 0.005). These findings suggest that lack of belief in God was associated with a more favorable view of restrictions implemented in places of worship (Figure IA). As for COVID-19 vaccination, a positive attitude was more frequently observed among non-religious individuals (77.19%) than among religious ones (66.32%). On the other hand, negative attitudes toward vaccination were more often declared by religious participants (33.68%) compared to non-religious ones (22.81%) (χ² = 8.14, df = 1, p = 0.004). These results suggest that religiosity was associated with greater skepticism toward COVID-19 vaccination (Figure IB).

Figure I

Religiosity, anxiety, and health-related attitudes toward COVID-19. A) Support for restrictions on the number of worshippers in places of worship was more frequent among non-religious individuals (75.34%) than religious ones (64.42%); χ2 = 7.79; p = 0.005. B) A positive attitude toward COVID-19 vaccination was higher in the non-religious group (77.19%) compared to the religious group (66.32%); χ2 = 8.14; p = 0.004. C) Compliance with preventive measures and anxiety levels: among individuals with high anxiety, religious respondents more often declared adherence to recommendations (96.19%) than non-religious ones (77.94%) – with low anxiety, the trend reversed (87.06% vs. 91.98%) and was χ2 = 6.95; p = 0.008 in both groups. Bars represent the percentage of affirmative responses; exact values are shown above each bar. Yellow indicates religious respondents, red indicates non-religious respondents

Religiosity and health-promoting attitudes: compliance with preventive measures, attitudes toward restrictions and COVID-19 vaccination – additional findings

The influence of religious denomination on attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemicwas diverse. No significant differences were found in adherence to preventive measures between religious affiliations. The highest compliance rates were observed among Catholics (92.31%) and members of other faiths (89.09%), while the lowest was among Protestants (77.78%). However, significant differences emerged regarding attitudes toward restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 30.16; df = 3; p < 0.001): the greatest support was expressed by members of other faiths (84.35%) and Catholics (70.71%), with the lowest support among Orthodox Christians (45.60%). Regarding vaccination (χ² = 16.59; df = 3; p = 0.001), the most positive attitudes were reported by Protestants (87.50%), followed by Catholics (67.19%) and the lowest among Orthodox Christians (55.64%).

Belief in God’s healing power did not significantly influence adherence to preventive measures, with high compliance rates in all groups: 88.31% among those who believed in divine healing, 87.50% among those who did not, and 95.31% among undecided individuals. However, significant differences were found regarding attitudes toward restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 32.31; df = 2; p < 0.001): highest support was expressed by the undecided (92.73%) and those who did not believe in divine healing (78.85%), and the lowest by believers (56.12%). Similar differences were found in attitudes towards vaccination (χ² = 15.38; df = 2; p < 0.001): positive attitudes were declared by 60.54% of believers, 81.82% of the undecided, and 81.13% of non-believers.

Experiencing healing through God did not significantly affect adherence to preventive measures, which remained high across all groups: 88.19% among those who reported divine healing, 94.05% among those who had not, and 88.03% among undecided individuals. Significant differences appeared in attitudes toward restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 12.85; df = 2; p = 0.002): support was expressed by 76.92% of non-healed respondents, 66.17% of the undecided, and only 51.89% of those claiming to have been healed. Attitudes toward vaccination did not differ significantly; however, the highest support was among non-healed individuals (75.32%) and the lowest among those who reported healing (59.81%).

Faith as a source of inner peace. Individuals who viewed faith as a source of inner peace were less likely to support both restrictions in churches and vaccination compared to those who did not share this view. Compliance with preventive measures remained high across all groups, with no significant differences: 88.82% among those who derived peace from faith, 86.21% among those who did not, and 95.74% among the undecided. However, significant differences were observed regarding support for restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 19.22; df = 2; p < 0.001): the highest support came from those who did not find inner peace in faith (86.27%) and the undecided (79.07%), while the lowest came from those who did (58.42%). In terms of vaccination (χ² = 6.75; df = 2; p = 0.034), support was highest among those who did not find peace in faith (82.35%) and lowest among those who did (63.95%).

Faith as support in coping with fear of infection. Perceiving faith as helpful in dealing with fear of infection did not significantly influence compliance with preventive measures, which remained high: 88.12% among those who felt supported by faith, 90.20% among those who did not, and 91.46% in the undecided group. Significant differences were found in attitudes toward restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 31.38; df = 2; p < 0.001): those who found support in faith were least likely to support restrictions (53.33%) compared to those who did not (84.95%) and the undecided (73.13%). Similar differences were found regarding vaccination (χ² = 22.17; df = 2; p < 0.001): lowest support was among those who felt supported by faith (57.14%), and highest among those who did not (83.70%).

Prayer as a stress-relief strategy. Attributing stress-relieving properties to prayer did not significantly influence compliance with preventive measures, which remained high: 88.46% among those who viewed prayer as helpful, 87.50% among those who did not, and 95.08% among the undecided. However, significant differences were observed regarding support for restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 17.53; df = 2; p < 0.001): the lowest support came from those who found prayer helpful (57.89%), compared to those who did not (81.54%) and the undecided (78.00%). Differences also appeared in attitudes toward vaccination (χ² = 15.26; df = 2; p < 0.001): the lowest support was among those who viewed prayer as stress-relieving (60.22%), and the highest among those who did not (83.33%).

Perceiving the pandemic as a test of faith. Viewing the pandemic as a test of faith did not significantly affect compliance with preventive measures. High adherence was reported across all groups: 84.50% among those who viewed the pandemic as a test, 89.59% among those who did not, and 94.68% among the undecided. Significant differences were found in support for restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 23.81; df = 2; p < 0.001): the lowest support was among those who perceived the pandemic as a test of faith (47.32%), compared to those who did not (74.75%) and the undecided (66.86%). Attitudes toward vaccination (χ² = 14.00; df = 2; p = 0.001) showed the lowest support in the group viewing the pandemic as a test of faith (60.00%) and the highest among those with the opposite view (73.62%).

Perceiving the pandemic as divine punishment for sin. Seeing the pandemic as punishment for humanity’s sins did not significantly impact compliance with preventive measures, which remained high: 89.66% among those holding this belief, 87.88% among those who did not, and 93.33% among the undecided. Significant differences were observed in support for restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 14.12; df = 2; p = 0.001): the lowest support was among those viewing the pandemic as punishment (48.00%), compared to those who disagreed (70.37%) and the undecided (52.31%). Regarding vaccination (χ² = 10.78; df = 2; p = 0.005), the lowest support was among those who perceived the pandemic as divine punishment (47.92%) and the highest among those with opposing beliefs (71.05%).

Use of clerical support. Using spiritual support from clergy did not significantly affect adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures. High compliance was observed among both those who used such support (86.19%) and those who did not (91.29%). Significant differences were noted regarding support for restrictions in places of worship (χ² = 30.47; df = 1; p < 0.001): those who received support from clergy were less likely to support the restrictions (48.78%) compared to those who did not (76.02%). No significant differences were found in attitudes towards vaccination, although non-users of clerical support more frequently expressed positive attitudes (69.91%) compared to users (61.35%).

The relationship between anxiety levels and positive attitudes toward compliance with preventive measures, support for restrictions, and attitudes toward vaccination among religious and non-religious individuals

Descriptive statistics for the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S, Polish version) were presented for both religious and non-religious groups [24].

Relationship between anxiety levels and health-promoting attitudes

Analysis of the relationship between anxiety levels and health-promoting attitudes showed that the mean anxiety score was 14.60 (SD = 6.62) in the non-religious group and 14.90 (SD = 6.09) in the religious group. These differences were not statistically significant.

Religious individuals: high vs. low anxiety levels

Among religious individuals, those with a high level of anxiety were significantly more likely to comply with preventive measures (96.19%) compared to those with a low level of anxiety (87.06%) (χ² = 6.95; df = 1; p = 0.008). No statistically significant differences were observed regarding support for restrictions in places of worship or attitudes toward vaccination (Figure IC).

Non-religious individuals: high vs. low anxiety levels

Among non-religious individuals, those with a high level of anxiety were also significantly more likely to comply with preventive measures (91.98%) than those with low levels (77.94%) (χ² = 6.95; df = 1; p = 0.008). Again, no significant differences were found in support for restrictions in places of worship or attitudes toward vaccination (Figure IC).

For the remaining dependent variables – support for sanitary restrictions in places of worship and positive attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination – no statistically significant differences were found in either the religious or non-religious groups.

Anxiety levels and preferred coping strategies during the pandemic among religious and non-religious individuals

Student’s t-test analysis revealed differences in preferred coping strategies depending on anxiety levels in both religious and non-religious participants.

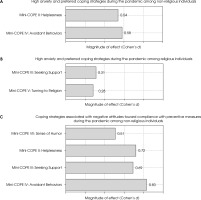

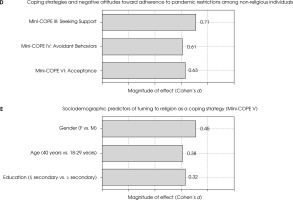

Non-religious group

In the non-religious group, significant differences were found in two stress-coping strategies. Individuals with high anxiety more frequently used strategies associated with the Helplessness factor (Mini-COPE Factor II): t(33) = 1.55; p < 0.05. The effect size was moderate (Cohen’s d = 0.54). They also more frequently selected strategies from the Avoidant Behaviors factor (Mini-COPE Factor IV): t(33) = 1.88; p < 0.05. This effect was also moderate (Cohen’s d = 0.58). No significant differences were observed for the remaining coping strategies (Figure IIA).

Religious group

In the religious group, different patterns emerged. Individuals with high anxiety levels more often used Seeking Social Support strategies (Mini-COPE Factor III): t(250)= –1.38; p < 0.05. However, the effect was weak (Cohen’s d = 0.31). They also more frequently chose Turning to Religion strategies (Mini-COPE Factor V): t(250) = –1.28; p < 0.05. Again, the effect was weak (Cohen’s d = 0.28). As in the non-religious group, no significant differences were found in the remaining coping strategies (Figure IIB).

Health-promoting attitudes and preferred coping strategies during the pandemic among religious and non-religious individuals

Student’s t-test analysis revealed differences in coping strategies between individuals with positive and negative health-promoting attitudes in both religious and non-religious groups.

Compliance with preventive measures

In the group of non-religious individuals, statistically significant differences were observed in four coping strategies. Participants who did not comply with preventive measures significantly more often used strategies related to helplessness (Mini-COPE Factor II; t(33) = 1.92; p < 0.05; Cohen’s d = 0.72), sought social support more frequently (Factor III; t(33) = 1.76; p < 0.05; d = 0.69), employed avoidant behaviors (Factor IV; t(33) = 2.14; p < 0.05; d = 0.83), and relied on humor (Factor VII; t(33) = 1.35; p < 0.05; d = 0.51).

Figure II

Coping strategies (mini-COPE) in relation to anxiety, attitudes toward restrictions, and sociodemographic variables. A) Non-religious individuals with high levels of anxiety more frequently chose Helplessness (II) and Avoidant Behaviors (IV) (moderate effects; d = 0.54–0.58). B) Among religious individuals, high anxiety was associated with more frequent use of Seeking Support (III) and Turning to Religion (V) (small effects; d = 0.28–0.31). C) A negative attitude toward preventive recommendations in the non-religious group was associated with more frequent use of Avoidant Behaviors (IV), Helplessness (II), Seeking Support (III), and Sense of Humor (VII) (moderate to large effects; d = 0.51–0.83). D) A negative view of pandemic restrictions among non-religious individuals was linked to more frequent use of Seeking Support (III), Avoidant Behaviors (IV), and Acceptance (VI) (moderate effects; d ≈ 0.60–0.75). E) More frequent use of Turning to Religion (V) was observed among women, individuals aged ≥ 40 years, and those with secondary or lower education (small to moderate effects; d = 0.32–0.45). Effect sizes are presented using Cohen’s d scale (d ≈ 0.20 – small, 0.50 – moderate, ≥ 0.80 – large). Positive values indicate higher intensity of the coping strategy in the first of the groups compared D) A negative view of pandemic restrictions among non-religious individuals was linked to more frequent use of Seeking Support (III), Avoidant Behaviors (IV), and Acceptance (VI) (moderate effects; d ≈ 0.60–0.75). E) More frequent use of Turning to Religion (V) was observed among women, individuals aged ≥ 40 years, and those with secondary or lower education (small to moderate effects; d = 0.32–0.45). Effect sizes are presented using Cohen’s d scale (d ≈ 0.20 – small, 0.50 – moderate, ≥ 0.80 – large). Positive values indicate higher intensity of the coping strategy in the first of the groups compared

All these effects ranged from moderate to strong in terms of magnitude. In contrast, within the group of religious individuals only one significant difference emerged: those who opposed preventive measures more frequently used strategies based on seeking support (Factor III; t(250) = 1.67; p < 0.05), although the effect size was small (Cohen’s d = 0.26) (Figure IIC).

Support for restrictions in places of worship

In the context of support for restrictions in places of worship, non-religious individuals who opposed such restrictions more often used strategies associated with seeking social support (t(33) = 2.13; p < 0.05), avoidant behaviors (t(33) = 1.84; p < 0.05), and acceptance (t(33) = 1.75; p < 0.05). All effects in this group were of moderate strength (Cohen’s d = 0.71, 0.61, and 0.63, respectively). Among religious respondents, a positive attitude toward restrictions in places of worship was related to a more frequent use of helplessness strategies (Factor II; t(250) = –1.49; p < 0.05), turning to religion (Factor V; t(250) = –1.65; p < 0.05), and humor (Factor VII; t(250) = –1.44; p < 0.05). However, the effect sizes in these cases were weak (Co-hen’s d between 0.22 and 0.28) (Figure IID).

Importantly, the analysis of the relationship between positive attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination and coping strategies revealed no statistically significant differences in either the religious or non-religious groups. This suggests that while some coping strategies were linked to compliance with preventive behaviors and opinions on religious restrictions, they were not related to vaccination attitudes in this sample.

The influence of sociodemographic characteristics on the use of the “turning to religion” coping strategy

Comparative analysis revealed that the “turning to religion” strategy (Mini-COPE V) significantly differed depending on participants’ gender, age, and level of education (hypothesis 5).

Women reported a notably higher mean score (M = 2.88; SD = 0.91) than men (M = 2.48; SD = 1.02), as confirmed by a Student’s t-test (t(634) = 4.12; p < 0.001) with a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.45). A similar trend was observed for age: participants aged ≥ 40 years more frequently used this strategy (M = 2.95; SD = 0.87) compared to those aged 18-29 years (M = 2.57; SD = 0.95), (t(373) = 3.15; p = 0.002; Cohen’s d = 0.38). Educational level also differentiated the intensity of religious coping: individuals with secondary education or lower scored higher (M = 2.83; SD = 0.93) than those with higher education (M = 2.57; SD = 0.96), (t(310) = 2.66; p = 0.008; Cohen’s d = 0.32). In contrast, place of residence (urban vs. rural) and occupational status (employed vs. unemployed) did not significantly influence the proportion of individuals characterized by a high level of “turning to religion,” as indicated by non-significant χ² test results (all p > 0.10).

These findings support hypothesis 5 regarding gender, age, and education, suggesting that individual demographic characteristics – rather than environmental context – play a key role in shaping the use of religious coping during the pandemic (Figure IIE).

DISCUSSION

This study focused on the relationship between religiosity and health-promoting attitudes toward COVID-19, including compliance with restrictions and attitudes toward vaccination. It also examined the influence of pandemic-related anxiety on these attitudes and explored preferred coping strategies depending on anxiety levels.

With regard to the first hypothesis (which was not confirmed), the analysis showed no significant differences in compliance with preventive measures between believers (89.21%) and non-believers (88.24%). However, differences did emerge in attitudes toward pandemic restrictions and vaccination. Non-believers more frequently supported restrictions in places of worship (75.34%) compared to believers (64.42%). Similarly, non-believers were more likely to express positive attitudes toward vaccination (77.19%) than believers (66.32%). Findings from other studies appear to be consistent with these observations, explaining the complex interactions between religion, religiosity, and the COVID-19 pandemic [25]. Religious gatherings and related ritual activities contributed to the transmission of COVID-19 worldwide, as evidenced by numerous studies [25-30]. Some religious leaders, perceiving the pandemic as an act of divine will, refused to alter their rituals, believing that God – not government – determines life and death. Religious resistance and the promotion of harmful beliefs led to the rejection of governmental recommendations, further fueling the spread of the virus [29, 31-33]. Disinformation also played a significant role, particularly within some religious communities. The spread of false claims about vaccines, their alleged side effects, or supposed conflicts with religious doctrine likely contributed to anti-vaccine attitudes. Studies have shown that conspiracy theories such as “microchips in vaccines,” “the mark of the beast,” or “a human experiment” circulated in some religious groups, increasing distrust toward medicine and public institutions [34]. Followers of more radical or orthodox religious ideologies were less likely to comply with pandemic restrictions [31]. Some studies indicated that higher levels of religiosity were associated with greater belief in COVID-19-related misinformation and resistance to vaccination, especially among conservative believers [34-36]. At the same time, certain religious leaders and communities actively supported adaptation to safety measures, helping to strengthen social bonds and build emotional resilience [25, 37]. Detailed numerical results supporting these differences can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

Regarding the second hypothesis (partially confirmed, but only in the context of general preventive behavior), our study showed that among religious participants individuals with high anxiety levels were significantly more likely to follow preventive guidelines (96.19%) compared to those with low anxiety (87.06%; p = 0.008). A similar pattern was observed among non-believers: individuals with high anxiety were more compliant (91.98%) than those with low anxiety (77.94%; p = 0.008). Anxiety levels did not significantly influence support for religious restrictions or attitudes toward vaccination in either group (p > 0.05). These findings indicate that fear of COVID-19 was a significant predictor of health-related behaviors such as social distancing and hygiene, regardless of religious belief. This is consistent with existing literature identifying fear and anxiety as motivators for following public health guidelines [38]. However, it has also been noted that spirituality can mitigate the negative impact of anxiety on mental health. Studies from Malaysia and Portugal demonstrated that higher spirituality was associated with reduced anxiety and fewer mental health issues during the pandemic [39, 40]. The influence of spirituality may be ambivalent – it can be protective but may also intensify anxiety symptoms, particularly when associated with apocalyptic or conspiratorial beliefs [41].

Table 2

Research questions and hypotheses

Table 3

Independent and dependent variables with their indicators

The findings related to the third and fourth hypotheses (both of which were confirmed) showed that religious individuals preferred coping strategies based on spirituality and social support, while non-believers more often relied on defensive strategies such as helplessness and avoidance. Although the effect sizes were small, these findings underscore the role of religiosity and emotional support in stress regulation. The results align with previous studies suggesting that spirituality can provide meaning, purpose, and hope [40, 42], and that religious communities offer emotional and spiritual support that enhances psychological well-being and resilience in times of crisis [8, 10, 42-44]. While non-religious individuals more often turn to defensive strategies, they may also benefit from secular self-regulation methods such as mindfulness or social engagement [45]. Nevertheless, independent studies have demonstrated that spiritual meditation outperforms secular meditation and relaxation in terms of therapeutic effectiveness [10, 18, 46, 47].

The results fully confirmed hypothesis 5, showing that the “turning to religion” strategy was significantly more common among women, individuals aged forty and above, and respondents with no more than secondary education. Neither place of residence nor occupational status differentiated the intensity of this coping strategy. These patterns may be interpreted as reflecting traditional gender roles, intensified existential needs among older adults, and the compensatory function of religion in groups with lower educational capital. In practical terms, this suggests that programs combining psychological support with spiritual elements should primarily target these three populations. However, it is important to note that the sociodemographic analyses were post hoc in nature and based on correlational data; therefore, the observed effects require confirmation in further, more targeted studies.

Study limitations

Although surveys allow for rapid and cost-effective data collection, results may be biased by respondents’ desire to present themselves in a favorable light or by varying interpretations of response scales. Surveys capture a momentary state rather than long-term behavior, and their length can discourage participation, potentially lowering data quality. In the present study, limitations included reliance on self-reported declarations rather than observable behaviors and incomplete responses from some participants. Additionally, the analysis of the influence of sociodemographic variables was post hoc in nature and based on a cross-sectional, correlational data design, which limits the ability to draw causal inferences. Additionally, although the original questionnaire was reviewed by experts, it was not subject to formal psychometric validation procedures, which may limit the interpretability of some findings.

Possible directions for future research

Future studies could explore the relationship between spirituality and psychological resilience in the face of pandemic-related stress and threats, as well as the role of social support within religious communities. It would be valuable to investigate how religious groups provide emotional and spiritual support during health crises. Additionally, an analysis of historical responses of religious groups to past pandemics could offer insights into the factors that foster readiness for health-promoting behaviors and strengthen public health compliance. Longitudinal and experimental studies are needed that account for gender, age, and education level, as well as integrate self-reported data with objective indicators of health-related behaviors, in order to verify the stability and direction of the observed relationships.

CONCLUSIONS

The study demonstrated that religiosity influences health-related attitudes during a pandemic. Believers were less likely to adhere to preventive guidelines, as they tended to believe their health was in God’s hands, which reduced their perceived responsibility for protective actions. However, high levels of pandemic-related anxiety increased their willingness to comply with public health recommendations. While the majority of believers (73%) reported belief in divine healing, only 25% claimed to have actually experienced such a miracle. Despite these varied experiences, 59% of participants stated that religiosity helped them cope with stress and pandemic-related anxiety. Nevertheless, 23% of believers reported that faith alone was insufficient in overcoming fear. Furthermore, it was shown that women, individuals aged ≥ 40 years, and respondents with secondary education or lower were more likely to use the “turning to religion” strategy, suggesting that the effectiveness of religious coping may depend on the demographic profile of individuals. Non-religious participants were more likely to report reliance on scientific sources when forming their opinions and showed greater readiness to follow preventive recommendations. In the non-religious group, lower anxiety levels were associated with proactive health behaviors (e.g., vaccination), whereas higher anxiety levels corresponded to more reactive strategies, such as strict adherence to isolation measures without active engagement in public discourse.

As a result, religiosity may both support stress coping and undermine motivation to follow health guidelines, with anxiety levels and sociodemographic variables playing a key role in this dynamic.