INTRODUCTION

In humans, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) is a multifaceted limbic structure that is functionally integrated with the amygdala through the stria terminalis. The first formal description of the BNST as a gray matter entity enveloping the stria terminalis, with distinct rostral and caudal components, was provided by Johnston in 1923 [1]. The rostral part, originally noted by Johnston, is now conventionally identified as the BNST. Structurally, it is located inferior to the lateral septal complex and superior to the hypothalamic preoptic area [1]. The caudal extension of the BNST is integrated with amygdaloid structures, forming a functional and anatomical continuum [2]. Contemporary studies have identified two major subdivisions within this system: the medial region, which includes the medial amygdaloid nucleus, and the central region, which is characterized by connectivity between the central amygdaloid nucleus and the lateral BNST. The notion that the BNST and centromedial amygdala constitute a shared neural system has been reinforced by research highlighting overlapping morphological and neurochemical properties [3, 4]. Based on this strong anatomical and functional integration, Heimer et al. [5] conceptualized the “extended amygdala”.

In addition to the BNST and centromedial amygdala, the extended amygdala includes the sublenticular substantia innominata and the nucleus accumbens (NAc). Furthermore, Heimer et al. [5] contributed significantly to the development of the ventral striatum model and its relationship with parallel basal ganglia circuitry.

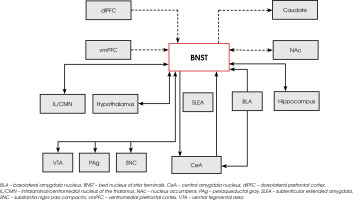

The BNST forms extensive connections with both cortical and subcortical networks, which regulate anxiety, addiction-related behaviors, and both neuroendocrine and autonomic stress responses [6]. Anxiety and addiction are major components of psychiatric disorders, with stress serving as a key catalyst for both conditions [6]. The BNST plays a pivotal role in modulating the neuroendocrine and autonomic stress response [6]. It is intricately connected to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, which constitutes the core of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, initiating cortical stress responses. Additionally, hippocampal projections pass through the BNST to influence the HPA axis, forming a psychogenic circuit that integrates limbic processing, emotional valence assessment, and behavioral responses to stress and anxiety [7]. The BNST’s neuro-anatomical connectivity with circuits governing limbic, autonomic, neuroendocrine, and somatic regulation is depicted in Figure I.

Among the most disabling psychiatric disorders, anxiety-related conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder remain prevalent [8]. Another significant disorder, treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (trOCD), was originally categorized under anxiety disorders in the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), but has been reclassified under a distinct obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder category in the 5th edition of DSM. However, despite this reclassification, OCD-related obsessions continue to induce severe anxiety, driving compulsions that serve to alleviate panic symptoms [9].

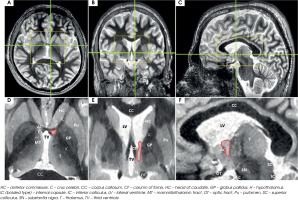

This review highlights the BNST region as a potential neuromodulation target in the treatment of trOCD and treatment-resistant depression (TRD). The term BNST area is used instead of the BNST alone, as its proximity to other DBS targets for trOCD and TRD is minimal. Several crucial DBS sites, including the NAc, ventral part of the anterior limb of the internal capsule (vALIC), or the inferior thalamic peduncle (ITP), cluster around the BNST. Due to the volume of tissue activated (VTA) by electrical stimulation, their effects frequently overlap. Figure II displays the spatial relationship of these adjacent structures in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Additionally, this review compiles all existing clinical evidence on DBS of the BNST area for trOCD and TRD.

Figure I

Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) anatomical connections with other brain structures regulating limbic, autonomic, neuroendocrine and somatic functions in humans. Dotted lines represent BNST functional connectivity with cortical and subcortical brain regions detected by using the power of ultra-high field (7 Tesla functional magnetic resonance imaging) for mapping functional connections in humans. Box sizes and boxes locations are arbitrary

Figure II

Axial magnetic resonance imaging using fast gray matter acquisition T1 inversion recovery (FGATIR) sequence of the target area at the level of anterior commissure (AC) – posterior commissure (PC) plane. The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) with neighboring structures are over-laid on this AC-PC plane. The nucleus accumbens (NAc) and ventral part of the anterior limb of internal capsule (vALIC) are located 3 to 4 mm ventral to this AC-PC plane. The stereotactic trajectory is planned passing through the internal capsule to the BNST area. Structures adjacent to BNST (NAc, vALIC, inferior thalamic peduncles) are likely to be costimulated depending on the electrical settings and the stimulation mode provided by implanted deep brain stimulation electrodes

The purpose of this systematic literature review is to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of DBS targeting the BNST area in patients suffering from trOCD and TRD.

MATERIALS AND METHOD FOR SEARCHING FOR BNST DBS STUDIES ON TROCD AND TRD

A systematic literature search for publications regarding BNST DBS in trOCD and TRD was conducted, spanning the period from January 2010 to February 2025. The search was conducted in medical literature, analysis, and retrieval system on-line (MEDLINE) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial (Cochrane) databases. The following search phrases were used: MEDLINE – (“deep brain stimulation” [Mesh] OR “deep brain stimulation”) AND (“obsessive-compulsive disorder” OR “OCD” OR “treatment-resistant depression” OR “TRD”), yielding 1,271 records; and Cochrane – (“deep brain stimulation” OR “DBS”) AND (“obsessive-compulsive disorder” OR “OCD” OR “treatment-resistant depression” OR “TRD”), yielding 221 records.

No restrictions were placed on study design. We included prospective and retrospective clinical studies and case series. Only research articles published in English and involving humans were considered. Studies incorporating patients with different DBS targets, but also those in which BNST was used for the treatment of trOCD and TRD were also assessed in the present analysis. Although the placebo effect is very strong for all functional neuro-surgical procedures, especially in neuropsychiatry, we did not set the limit of follow-up period due to the relatively small number of published clinical studies and case reports regarding the clinical utilization of BNST DBS for trOCD and TRD.

Figure III

PRISMA 2020 flowchart illustrating the selection process of studies included in this systematic review

Exclusion criteria comprised animal studies, studies that included treatment of trOCD and TRD without DBS, review articles, letters to the editor and duplicate studies. Additionally, the exclusion criteria constituted articles describing patient populations other than those with trOCD and TRD and reports that mainly dealt with aspects related to the surgical technique. The search strategy followed PRISMA 2020 guidelines and is illustrated in Figure III. The search of the two databases using the aforementioned keywords yielded 1,492 articles. Using the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above, we identified 8 articles suitable for further analysis; these are discussed below.

Two reviewers (M.S., K.K.) independently screened titles and abstracts. The full texts of potentially eligible studies were assessed. Data on sample size, DBS target, outcome measures, follow-up duration, and adverse effects were extracted and tabulated.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES OF DBS FOR TROCD

The trOCD severely impacts an individual’s ability to function in multiple areas of life, including personal relationships, professional responsibilities, and social interactions. Despite prolonged use of pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions, many patients do not achieve symptom relief. When conventional treatment options were exhausted, ablative surgical interventions, such as anterior capsulotomy, were historically considered the last resort [10]. Initially, classical capsulotomy techniques were performed approximately 1 centimeter rostral to the anterior commissure (AC), targeting the anterior limb of the internal capsule (IC) [10]. However, over time clinical research has demonstrated that capsulotomy procedures conducted at more posterior sites yield greater therapeutic benefits. A similar observation was made in the early experience of Nuttin et al. [11, 12], who initially placed DBS electrodes on a classical capsulotomy target. Due to limited clinical effectiveness and high energy demands, these researchers repositioned DBS leads into deeper and more posterior regions of the IC, shifting the target towards the BNST [13]. The BNST is clearly distinguishable in axial, sagittal, and coronal MRI sequences, positioned posterior to the AC and lateral to the fornix (Figure IV).

Figure IV

Axial (left), coronal (middle), and sagittal (right) images of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis generated using Fast Gray Matter Acquisition T1 Inversion Recovery (FGATIR) sequence. The position of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is highlighted in red outline. Green lines in top row indicate corresponding cuts in other axes. Yellow boxes in the top row show brain regions magnified in the lower row. Coronal cut is 1 mm posterior to the posterior aspect of the anterior commissure. The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is bounded laterally by the internal capsule, medially by the fornix, and anteriorly by anterior commissure

The significance of adjusting DBS lead-positioning has been highlighted by multiple research teams, who observed that posterior stimulation at the vALIC/BNST interface resulted in better clinical outcomes for trOCD patients [13, 14]. Greenberg et al. [14], investigated the correlation between lead implantation sites and clinical efficacy, analyzing a cohort of 26 patients divided into 3 groups [14]. In the earliest patient subgroup, where DBS was implanted in a region aligned with classical capsulotomy targets (15 mm anterior to AC), bilateral ALIC stimulation led to only modest clinical improvements. In contrast, shifting DBS leads to more caudal and posterior locations, specifically the NAc, resulted in progressively enhanced symptom relief. Patients who underwent ALIC/BNST-targeted DBS experienced a mean reduction of 54.3% in Y-BOCS scores, whereas those receiving stimulation at the ALIC alone demonstrated only a 29% reduction [14]. Additionally, 77.8% of patients in the ALIC/BNST cohort achieved full response criteria, compared to 33.3% in the ALIC-stimulated group [14]. Notably, individuals receiving stimulation at the ALIC/BNST site exhibited fewer stimulation-induced adverse events, further supporting the hypothesis that posterior DBS targeting lowers the energy requirements for effective neuromodulation, thereby reducing complications [13].

A long-term follow-up study by Luyten et al. [13], included 24 trOCD patients implanted with DBS leads in either the ALIC or BNST [13]. The authors investigated how lead location influenced clinical outcomes [13]. The patient population was divided into 3 distinct groups: those with DBS leads primarily stimulating the ALIC (6 patients), the BNST (15 patients), and an overlapping group with stimulation affecting both regions equally (3 patients). A median improvement of 37% in Y-BOCS scores was reported when comparing the blinded ON phase (median Y-BOCS score: 20) to the OFF phase (median Y-BOCS score: 32). Using a ≥35% Y-BOCS improvement as the benchmark for defining therapeutic success, 5 ALIC-stimulated patients showed insufficient response at the final follow-up, while only 1 ALIC patient demonstrated significant improvement. Conversely, in the BNST-stimulated group 12 out of 15 patients achieved meaningful clinical benefits, with an average Y-BOCS reduction of 50%, compared to only 22% for ALIC stimulation [13]. Among the 3 patients who received comparable stimulation in both areas, the mean Y-BOCS improvement reached 66%, suggesting that dual-region stimulation may enhance therapeutic efficacy. Interestingly, at the final follow-up stimulation was discontinued in 50% (3/6) of the ALIC-stimulated patients, whereas only 20% (3/15) of the BNST-stimulated patients had their DBS turned off [13].

A single-center case series study conducted by Far-rand et al. [16], further supported the notion that DBS targeting the NAc and BNST leads to effective symptom control in trOCD patients. In their cohort of 7 patients, 3 achieved a full response, 2 demonstrated partial improvement, and 2 were classified as non-responders. Interestingly, among those who fully responded symptom relief was observed despite variations in lead placement, indicating that DBS efficacy may not be solely dependent on a single precise anatomical target.

Three recent publications from 2021 presented further evidence regarding DBS treatment for trOCD [17-19]. Naesstrom et al. [17], reported an average Y-BOCS reduction of 38% at 12-month follow-up in a cohort of 11 patients. Within this group, 6 patients were full responders, 4 were partial responders, and 1 was a non-responder [17]. Conversely, Winter et al. [18], found that DBS targeting ALIC was more effective than BNST stimulation in treating trOCD. According to their findings, BNST DBS provided no significant clinical benefit, as none of the patients exhibited meaningful symptom improvement from direct BNST stimulation [18]. On the other hand, Mosley et al. [19], in a randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled trial spanning 3 months followed by a 12-month open label phase found that 7 out of 9 patients with trOCD were classified as responders. The mean Y-BOCS improvement reached 49.6 ± 23.7% with no hardware or stimulation induced adverse events [19]. The most recently published study, by Shofty et al. [20], found that VS/BNST DBS remains an effective treatment option for patients with trOCD. These authors used the awake DBS technique with trajectories planned for both VS and BNST targets bilaterally. The authors intraoperatively assessed the acute effects of stimulation on mood, energy, and anxiety and chose the trajectory with the most reliable positive valence responses and least stimulation-induced side effects [20]. Among 8 patients with trOCD 44% of leads were moved to the BNST region, resulting in a Y-BOCS score reduction across the full cohort of 51.2 ± 12.8% at 21 months [20].

The clinical outcomes of BNST DBS for trOCD are detailed in chronological order in Table 1. The reduction of the Y-OCBS in the reported studies ranged from 27% to 66%, with a mean reduction of 45% in the Y-BOCS scores at a mean of 58 months postoperatively. Although the BNST may be the preferred near-future target to be approached with DBS, many authors still argue that ALIC, NAc, VS are effective DBS targets in the treatment of patients suffering from trOCD [21-24]. Studies performed on larger patient populations with the assessment of VTA by directional DBS leads may bring the answer to the question of which structure is more effective in ameliorating trOCD symptoms. Naesstrom et al. [25], studied the distribution of VTA in patients with trOCD after BNST DBS [25]. These authors found that the VTAs produced by large field of stimulation overlap targets such as the NAc, ALIC, the ventral part of IC and ITP. Data is still missing on how various stimulation parameters in a given target will affect surrounding small anatomical areas and impact the clinical outcome of DBS. One solution will be the previously stated utilization of directional DBS leads with more focused field stimulation [25].

Table 1

Clinical studies reporting the outcomes of bed nucleus of stria terminalis deep brain stimulation BNST DBS for OCD patients presenting the mean percentage of Y-BOCS scores reduction with response rate for individual studies. The clinical studies are presented in chronological order

[i] ALIO – anterior limb of internal capsule, AN – anorexia nervosa, BNST – bed nucleus of stria terminalis, DBS – deep brain stimulation, NAc – nucleus accumbens, MDD – major depressive disorder, MFB – medial forebrain bundle, OCD – obsessive compulsive disorder, vALIC – ventral part of the anterior limb of internal capsule, VS/VC – ventral striatum/ventral capsule, Y-BOCS – Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale

CLINICAL OUTCOMES OF BNST DBS FOR DEPRESSIVE AND ANXIETY SYMPTOMS IN OCD AND TRD

Comorbid depressive symptoms and non-OCD anxiety are frequently observed in patients with trOCD. Individuals affected by both trOCD and anxiety disorders often experience hopelessness, sadness, and an inability to derive pleasure from life, which are hallmark features of clinical depression. Both preclinical and clinical research strongly support the critical role of the BNST in regulating not only anxiety responses but also the pathophysiology of mood disorders. Furthermore, evidence suggests that the BNST is engaged in prolonged and gradually emerging neural responses to persistent threats [26]. This involvement may explain the BNST’s role in the development of long-term affective disorders following exposure to chronic stress [27-32].

Clinical studies in humans have identified abnormal oscillatory activity in the BNST among individuals diagnosed with trOCD and TRD [28]. In a study involving 7 patients with TRD implanted with DBS in the BNST, local field potential recordings revealed increased synchronized oscillatory activity within the alpha band [28]. These findings align with neuroimaging research, which has demonstrated heightened amygdala activity in TRD patients compared to healthy controls [29]. A more recent study investigating local field potentials in trOCD patients found an increase in synchronized oscillatory theta activity, with high-frequency DBS in the BNST/ ALIC region leading to a reduction in theta band oscillations, which was accompanied by clinical improvement in trOCD and affective symptoms [30]. Based on these findings, it is hypothesized that BNST DBS may exert its effects by suppressing excessive alpha oscillatory activity, given that the BNST serves as the primary output structure of the amygdala [29, 30].

In preclinical models of anxiety disorders, direct electrical stimulation of the BNST has been shown to produce notable anxiolytic and antidepressant effects [31, 32]. Moreover, clinical reports on patients receiving DBS in various brain regions, including the BNST for trOCD, have consistently documented significant improvements in co-occurring affective symptoms [13, 14]. The majority of studies investigating DBS for trOCD have also reported a reduction in depressive symptoms, as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) [13, 14, 17, 18]. Improvements in comorbid anxiety have also been frequently observed, with the exception of the study by Farrand et al. [16], who noted a 64% worsening of anxiety symptoms, as measured by the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-Anxiety subscale (DASS-A) [16].

To date, only 1 case report and 3 studies have directly examined the efficacy of BNST DBS for TRD. The first clinical application of BNST DBS is described in a case report on a 60-year-old woman who had a childhood onset of anxiety and comorbid intractable anorexia nervosa [33]. From age 44 her main problem was TRD, with anxiety. Initially, the patient underwent bilateral medial forebrain bundle (MFB) DBS, which yielded favorable outcomes for TRD. However, 2 years post-implantation, incapacitating blurred vision led to the discontinuation of MFB DBS. Following the transition to BNST DBS, the patient experienced gradual but profound improvements in depressive symptoms, alongside the stabilization of her anorexia nervosa and anxiety concerning food and eating [33]. The patient’s problems with food intake due to anorexia nervosa also improved. The feeding tube could be discontinued with less vomiting even after an in-take of larger portions of food [33]. The MFB is reported to be a valuable DBS target in TRD with a concomitant history of anorexia nervosa [34].

The first clinical trial of DBS in the IC/BNST region was presented by Raymaekers et al. [35]. This study was initiated on the basis of previous clinical observations suggesting that DBS in trOCD patients not only alleviates obsessive-compulsive symptoms but also improves severe depression and anxiety. The authors tested the hypothesis that DBS of the IC/BNST region might also provide the rapeutic benefits for TRD patients [35]. This double-blind crossover trial compared the outcomes of two different stimulation targets – BNST and the ITP – in 7 TRD patients [35]. During the two crossover periods within the first 16 months post-surgery, BNST stimulation demonstrated superior clinical outcomes compared to ITP stimulation. Three years after DBS implantation, all patients opted for stimulation at the BNST. At the final follow-up (63 months, range: 36-72 months), 5 of 7 patients were classified as responders, while 2 achieved complete remission. This study concluded that both BNST and ITP stimulation could contribute to symptom reduction in TRD patients [27]. Fitzgerard et al. [36] evaluated 5 patients undergoing bilateral BNST DBS. The results indicated sustained remission of depressive symptoms in 2 patients, with an additional 2 experiencing substantial therapeutic benefits, while the 5th patient showed minimal clinical response [36]. Recently, Wao et al. [37], published the outcomes of 23 TRD patients treated by BNST DBS, obtaining in 14 of them clinical responses assessed objectively with the HAM-D scale [37]. These authors found that electrode position analysis suggested that the BNST may be more important for the improvement of depressive symptoms than the NAc [37].

In summary, BNST DBS appears to alleviate not only obsessive-compulsive symptoms but also co-occurring affective symptoms, including depression and anxiety. The reduction of HAM-D scores in the reported studies ranged from 40% to 64%, with mean reduction of the HAM-D scores of 51% at the mean follow-up of 77 months. The patients’ comorbid depressive symptoms were also assessed using the MADRS scale and the clinical improvement ranged from 27% to 54.7% MADRS scores reduction when compared to preoperative MARDS scores. The mean improvement was 41% at a mean of 13.5 months. The improvement of comorbid anxiety in trOCD patients was not objectively reported in most studies but only 2 studies reported the detailed HAM-A scores pre and postoperatively. The mean improvement of HAM-A scores was 52% at a mean of 103 months postoperatively.

These objective psychiatric improvements are accompanied by functional gains, as reflected in enhanced Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores and other validated quality-of-life measures [13, 14, 16, 17, 28]. A comprehensive overview of clinical studies reporting BNST DBS outcomes for comorbid depressive symptoms in OCD, along with data on quality of life and socio-occupational functioning, are presented in Table 2.

ADVERSE EVENTS RELATED TO DBS OF THE BNST AREA FOR TROCD AND TRD

DBS procedures can be associated with various adverse effects, including intracranial hemorrhage, hardware-related complications, and stimulation-induced side effects. Among these, the most severe is massive intracranial bleeding leading to fatality. However, no cases of death or severe neurological deficits have been reported following DBS procedures targeting the BNST area for trOCD or TRD [13, 14, 16-19, 25, 27, 28, 33-37].

In the study by Greenberg et al. [14], 2 cases of intracerebral hemorrhage were observed among 26 patients, with 1 patient experiencing transient apathy for 3 months. Similarly, Luyten et al. [13], documented 2 cases of intracranial bleeding in 24 patients. The most frequently reported hardware-related complications involved DBS lead fractures, with 8 broken leads in the study by Luyten et al. [13], all of which were successfully managed through revision surgeries [19]. Additionally, DBS-related infections have been reported in various studies [14, 15, 17, 19].

A particularly noteworthy observation concerns the occurrence of epileptic seizures following BNST DBS [13, 14]. The highest incidence was documented by Luyten et al. [13], where 5 patients experienced seizures between 2 to 5 years post-implantation. Notably, interictal electroencephalographic abnormalities were absent, suggesting that the seizures were likely unrelated to DBS itself. However, this high incidence warrants further investigation. The BNST’s neural connections with the PVN of the hypothalamus, a critical component of the HPA axis, raise the possibility that stress (a major seizure trigger) may contribute to this phenomenon [35, 36]. Moreover, an overlap in neural circuits implicated in OCD and epilepsy has been suggested [29]. Interestingly, DBS of the thalamus and other brain regions has long been explored as a therapeutic approach for epilepsy [30-32]. Additionally, Greenberg et al. [14], reported a case of seizure in a patient who had undergone ALIC DBS implantation.

Stimulation-induced adverse effects vary across studies depending on the primary clinical indication for BNST DBS. In trOCD patients, such effects are frequently associated with mood alterations, manifesting as worsened depression, suicidal ideation, hypomania, irritability, insomnia, and heightened anxiety [13-15].

Patients with TRD who undergo BNST DBS require particularly close monitoring due to an observed increase in suicidal ideation and attempts [35, 36]. In 2 studies assessing adverse events in TRD patients, the most commonly reported side effects included worsening depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances [35-37]. In the study by Raymaekers et al. [35], all 7 patients reported some degree of increased depression at various points during follow-up. Notably, 2 patients committed suicide at 39 and 80 months post-DBS implantation, despite both being classified as responders and having a history of preoperative suicide attempts. In a separate study by Fitzgerald et al. [36], 2 out of 5 patients experienced suicidal ideation during follow-up, though without lasting consequences. One of these patients was classified as a non-responder, while the other was in remission. Additional psychiatric adverse effects included increased anxiety and episodes of tearfulness [36]. An interesting observation was made in the study by Raymaekers et al. [35], where a patient undergoing ITP DBS developed extrapyramidal-like symptoms, including hypomania, micrographia, freezing episodes, and less fluid movement, whereas patients receiving IC/BNST DBS did not exhibit such effects.

Preliminary findings suggest that trOCD patients may have a lower risk of suicide following DBS compared to TRD patients, irrespective of their responsiveness to treatment [13-18]. Therefore, TRD patients require more intensive monitoring to mitigate such risks. The fact that 2 suicide cases occurred despite strong postoperative psychiatric and neurosurgical care remains challenging to explain [35]. Patients who fail to respond to DBS may be at higher risk for suicidal ideation or suicide attempts during follow-up. Consequently, inclusion criteria for DBS in TRD patients may need to be reconsidered, potentially excluding individuals with a pre-existing history of suicidal behavior.

Stimulation-induced psychiatric adverse effects are commonly observed in patients who undergo DBS targeting the ventral striatum for trOCD or TRD. The close anatomical proximity of the BNST to other neuromodulation targets, including the NAc, vALIC, and ITP results in co-stimulation effects, which can contribute to mood-related changes [31, 35, 36]. To minimize such complications, stimulation parameters should be gradually increased, and intensive postoperative psychiatric and neuropsychological monitoring is essential. A structured multidisciplinary follow-up regimen is critical to reducing the risk of severe mood alterations [13-18, 35-37].

Table 2

Clinical studies reporting the outcomes of bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BNST) deep brain stimulation (DBS) for concomitant depressive symptoms accompanying obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Quality of life and socio-occupational functioning assessments using clinical scales are presented for each study

| Authors and year of publication | Indication for DBS | patients | Targets | Clinical outcomes for depressive symptoms (mean reduction to preoperative scores at the last follow-up) | Clinical outcomes for non-OCD-specific anxiety (mean improvement to preoperative scores at the last follow-up) | Sociooccupational functioning and quality of life assessment | Follow-up in moths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenberg et al., 2010 [14] | OCD | 26 | VS/VC vALIV/BNST | 40.0% (HAM-D) | 58.7 % (HAM-A) | Mean increase of 19.8 points in GAF | Up to 36 months |

| Islam et al., 2015 [15] | OCD | 8 | NAc/BNST | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Up to 60 months |

| Luyten et al., 2016 [13] | OCD | 24 | ALIC/BNST | 49% (HAM-D) | 45 % (HAM-A) | Mean increase of 30 points in GAF | Up to 171 months |

| Farrand et al., 2017 [16] | OCD | 7 | NAc/BNST | 23.3% (DASS-D subscale) | Mean deterioration of 64.2 % (DASS-A subscale) | Mean improvement of 37 % in SOFAS score | Up to 54 months average 18 months |

| Naesstrom et al., 2021 [17] | OCD | 11 | BNST | 27% MADRS | Not reported | Mean improvement of 12 % in GAF | 1 year |

| Winter et al., 2021 [18] | OCD | 6 | BNST/ALIC | Not reported | Not reported | Improved and assessed by WHOQoL-BRED | 4 to 8 years |

| Mosley et al., 2021 [19] | OCD | 9 | BNST | 54.7 ± 272 MADRS | Not reported | Not reported | 3 months controlled stimulation + 12 moths open label phase |

| Shofty et al., 2022 [20] | OCD | 8 | VS/VC/BNST | Improvement in comorbid depressive symptoms | Improvement in comorbid anxiety | Not reported | 21.25 ± 8 months |

[i] AN – anorexia nervosa, BMI – body mass index, DASS-A – Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-Anxiety subscale, DASS-D – Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-Depression subcale, GAF – global assessment of functioning, HAM-A – Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, HAM-D – Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, MADRS – Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, MDD – major depressive disorder, MFB – me-dial forebrain bundle, NAc – nucleus accumbens, QoL/SQ – Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, SOFAS – Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, Y-BOCS – Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, WHOQoL-BREF – World Health Organization Quality of Life-short form

It is important to emphasize that these adverse effects are not exclusive to BNST stimulation but rather stem from co-stimulation of adjacent ventral striatal structures. Incorporating VTA analysis, which models the electric field of the implanted DBS leads along with precise postoperative lead localization verification, may provide deeper insight into the true safety profile of BNST DBS in trOCD and TRD [25, 37].

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT STUDIES OF DBS OF THE BNST AREA FOR TROCD AND TRD

Existing clinical trials on BNST DBS provide preliminary insights into its efficacy and safety for trOCD and TRD. However, the strength of this evidence remains limited due to several factors. Among 8 studies reporting DBS for OCD in the BNST, 6 included patient cohorts receiving stimulation in neighboring regions, such as the ALIC or NAc [13-18].

Only 2 studies to date have investigated a homogeneous group of trOCD patients receiving BNST-targeted stimulation exclusively [17, 19]. Similarly, for TRD, BNST DBS has been evaluated in 3 studies, the first one comparing IC/BNST stimulation with ITP DBS, and the second one focusing solely on BNST stimulation, with the third assessing combined BNST/NAc stimulation [35-37].

Another limitation is that all studies conducted so far have been single-center, open-label trials, lacking sham-stimulation control groups, beside one study with a randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled design [13-19]. Consequently, these studies do not control for placebo effects, nor do they include comparison groups receiving optimized medical therapy, further limiting the robustness of clinical interpretations.

Additional variability is introduced by differences in DBS hardware, stimulation parameters, and programming protocols used by various research groups, complicating direct comparisons between studies. In functional neuro-surgery for movement disorders, epilepsy, and psychiatric conditions, a major confounding factor is the insertional effect [38-45]. This phenomenon refers to clinical improvement resulting from the surgical implantation of DBS electrodes itself, independent of active stimulation. Furthermore, functional neurosurgical procedures are known to elicit a strong placebo response, which, although it diminishes over time, can significantly influence short-term outcomes in epilepsy, trOCD, and TRD patients [46]. To mitigate the placebo effect in DBS trials for trOCD and TRD, follow-up periods should extend beyond 6 months.

Other external factors, such as fluctuations in the severity of psychiatric symptoms, changes in medication regimens, and life events further contribute to variability in treatment outcomes. These factors are difficult to control and may obscure the causal relationship between stimulation adjustments and clinical changes. The aforementioned limitations, including the small sample sizes, single-center open-label design, and multiple uncontrolled variables, highlight the challenges in evaluating the true efficacy of BNST DBS for trOCD and TRD.

CONCLUSIONS

DBS targeting the BNST for trOCD or TRD remains an experimental intervention that should still be further investigated. The clinical data available suggest that BNST stimulation may alleviate obsessive-compulsive symptoms and comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients who have failed all conventional treatment options, including pharmacotherapy, behavioral therapy, and electroconvulsive therapy. The cumulative reduction of the Y-OCBS in the reported studies ranged from 27% to 66%, with a mean reduction of 45% in the Y-BOCS scores at a mean of 58 months postoperatively. The reduction of comorbid depressive symptoms assessed by the HAM-D scale in the reported studies ranged from 40% to 64%, with a mean reduction of the HAM-D scores of 51% at the mean follow-up of 77 months. The improvement of comorbid anxiety in trOCD patients was not objectively reported in most studies, but only 2 studies reported the detailed HAM-A scores pre and postoperatively. The mean improvement of HAM-A scores was 52% at a mean of 103 months postoperatively.

However, several limitations remain. Clinical experience with BNST DBS is currently based on a limited number of patients who received stimulation in the BNST or adjacent structures. The occurrence of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, completed suicides, and hypomanic episodes raise concerns, though these adverse events are likely linked to the co-stimulation of neighboring regions, such as the NAc, vALIC, or ITP. Encouragingly, stimulation-related psychiatric side effects are often transient and can be managed through programming adjustments.

Given these risks and limitations, BNST DBS for trOCD or TRD should only be performed within controlled clinical trials led by multidisciplinary teams. Compared to vALIC or vALIC/BNST stimulation, BNST-targeted DBS may require lower stimulation parameters due to its smaller anatomical dimensions, potentially extending the lifespan of the implantable pulse generators. Utilization of directional DBS leads with estimation of VTA may increase responder rate, optimize stimulation parameters and focus electrical stimulation on the desired BNST-target.

While BNST DBS holds promise as a potential treatment for trOCD and TRD, its long-term safety and efficacy must be validated in well-designed, randomized, sham-controlled clinical trials before it can be considered a standard therapeutic option.