INTRODUCTION

Skin is the largest organ in the human body [1]. As it forms the external covering of the body, it is prone to various environmental insults with trauma being one of them [1]. Repair of skin tissue results in a broad spectrum of scar types, ranging from a “normal” fine line to a variety of abnormal scars, including widespread scars, atrophic scars, hypertrophic scars, and keloids [2]. Normal wound healing occurs in three consecutive phases: the inflammatory, the proliferative, and the remodeling phase. The inflammatory phase usually lasts for about 72 hours. It is characterised by platelet aggregation, cytokine release and infiltration of neutrophils at the site of injury. The proliferative phase begins with accumulation of cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) that forms a healthy granulation tissue under the influence of various growth factors like transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), interleukin family and angiogenic factors. The phase of remodelling lasts for several months. It consists of gradual degradation of excessive ECM and replacement of immature type III collagen by mature type I collagen [3]. The prolonged inflammatory phase overlapping with the later phases results in excessive scarring. A pathological difference between hypertrophic scars and keloids is that the dermal inflammation subsides over time in the former whereas it runs a protracted course in the latter [4].

Various local and systemic factors have been identified as contributors to the development of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Local factors include recurrent trauma, infection, and mechanical stress. Among these, mechanical forces appear to play a predominant role, as keloids often extend in the direction of tension surrounding the wound site. Systemic factors comprise hormonal fluctuations, hypertension, and chronic inflammation. Sex hormones may promote vasodilation, thereby intensifying inflammatory processes and favoring excessive scar formation. Hypertension induces vascular injury, which in turn amplifies the inflammatory response in adjacent tissues [5]. Patients with keloids and hypertrophic scars often complain of pain, pruritus, contractures, and restricted mobility. In addition, scars are frequently perceived as cosmetically disfiguring, which further contributes to the disease burden. The exact cause of pruritus in these patients remains unclear; however, recent studies suggest the potential involvement of cutaneous opioid receptors [6]. Overall, the quality of life in affected individuals is markedly impaired, with significant physical, psychological, and social consequences [7].

The distinction between keloids and hypertrophic scars is made clinically, primarily based on growth pattern and natural course. Hypertrophic scars are characterized by non-invasive growth that stabilizes over time and frequently end up with scar contracture [8]. With regard to treatment response, hypertrophic scars tend to be less resistant to therapy compared to keloids [8].

Histopathological examination of hypertrophic scars shows flattening of epidermis. Papillary and reticular dermis is replaced by scar tissue and the blood vessels show prominent vertical orientation [9]. Presence of cigar-shaped nodules oriented along the tension lines of the scar is characteristic [9]. These nodules contain high density of fibroblasts and collagen [9]. Alfa-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) positive myofibroblasts are also detected [9]. In contrast, keloids are characterized by an excessive deposition of keloidal collagen and a pronounced disorganization of fibrocollagenous fascicles [6]. The overlying epidermis and dermis usually appear normal, although a tongue-like advancing edge may be present beneath the dermis. Thickened hyalinized collagen is considered a histopathological hallmark of keloids, though it is not consistently detectable [6].

Currently, prevention of excessive scar formation is generally regarded as more effective than treatment [7]. Preventive strategies include tension-free primary wound closure, passive mechanical stabilization using paper tapes or silicone sheets, topical flavonoid preparations (e.g., Contractubex Gel), and pressure therapy. When scars develop, available treatment modalities encompass corticosteroids, surgical scar revision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, laser therapy, and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [10].

Intralesional steroid injections, steroid tapes/plasters and steroid ointments are conventional methods used to treat hypertrophic scars and keloids. Intralesional injections are the most common method for steroid administration, although steroid tapes/ plasters are gaining popularity. Steroids act through multiple mechanisms, most common being its antiinflammatory effect [10]. Other proposed mechanisms include antimitotic effect, reduction in plasma protease inhibitors thus reducing collagen synthesis, glycosaminoglycan production, fibroblast proliferation and degeneration of collagen and fibroblasts [10, 11]. Topical steroids act by binding to classical glucocorticoid receptors thereby inducing vasoconstriction resulting in reduced oxygen delivery to the wound bed [10, 11]. Keloids and hypertrophic scars treated with intralesional steroid injections show variable resolution rates ranging from 50% to 100% and recurrence rates of 9% to 50%. Steroids can be injected alone or in combination with other treatment modalities such as 5-FU, verapamil, cryotherapy or surgery. The concentration of triamcinolone acetonide varies from 10 to 40 mg/ml, but for monotherapy 40 mg/ml is recommended. The injection is performed 1–2 times a month until the scar has flattened [10]. Monotherapy is most effective in younger proliferative scars. Side effects include skin atrophy, telangiectasia, necrosis, ulceration, cushingoid habitus and linear hypopigmentation [12].

Emerging treatment strategies include mesenchymal stem cell therapy, fat grafting, interferon, botulinum toxin A, and bleomycin, among others.

Bleomycin is a cytotoxic, antineoplastic, antiviral and antibacterial agent derived from Streptomyces verticillus. It inhibits collagen synthesis due to inhibition of the enzyme lysyl oxidase and TGF-β. This mechanism of action is the basis of its use in keloids and hypertrophic scars [13]. In addition, it also induces apoptosis. Intralesional injections are the preferred delivery method, injected in a concentration of 1.5 IU/ml for two to six sessions at monthly intervals. Several studies reported that in 54% to 73% of keloid patients, complete flattening was achieved and other symptoms like itching and pain were also resolved [14, 15]. Possible adverse effects include injection site pain, ulceration, atrophy and hyperpigmentation, but systemic adverse effects are not observed [10]. Bleomycin can also be used in combination with other modalities, such as electroporation, which markedly potentiates its effects (by more than 10,000-fold). The advantage behind such combination is that it increases the permeability of cell membranes thereby allowing good penetration of the drug, which leads to increased efficacy without any increase in systemic toxicity [16].

Although a few studies have compared the effectiveness of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and intralesional bleomycin in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars, no such investigation has previously been conducted in India. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to address this gap by directly evaluating these two treatment modalities in the Indian population.

OBJECTIVE

To study the clinical efficacy and adverse effects of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars.

To study the clinical efficacy and adverse effects of intralesional bleomycin in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars.

To compare the clinical efficacy and safety of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and intralesional bleomycin in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

This hospital-based prospective study included a total of 170 patients who attended the outpatient Department of Dermatology at a tertiary care center over a period of 2 years. Ethical clearance from the institutional ethics committee was obtained before commencing the study (Ref no. IECJNMC/360).

The sample size was calculated by power calculator from the sealed envelopeTM for a continuous outcome non-inferiority trial using the following formula [17]: n = f (α, β) × 2 × σ2/d 2 , where, n – sample size, σ – standard deviation, d – non-inferiority limit.

Confidence interval and power was kept at 95% and 80%, respectively. Standard deviation of outcome was kept as 12.40 based on a study conducted by Khan et al. [18]. Total sample size obtained was 154. On adding a correction factor of 10%, it came out to be 169.4. Rounding off to whole numbers, total sample size of 170 was kept with 85 in each group.

Patients of keloids and hypertrophic scars were enrolled in the study after a detailed consent procedure. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant/lactating females.

Local/systemic infection.

Immunocompromised patients.

Previously treated patients (in the past 6 months).

Extensive keloids/hypertrophic scars (> 10% of body surface area).

Considering inclusion and exclusion criteria, 170 patients were selected. A detailed history of each patient was taken and recorded in proforma sheets designed for the study regarding demographic data of the patients (name, age, sex, occupation, residence), mode of onset, progression, duration, history of surgery, insect bite, burn injury, accidental trauma etc. General physical and systemic examination was performed. A complete cutaneous examination was done in all patients. Scoring was done using Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS). The POSAS consists of two scales: the observer scale and the patient scale. Each scale includes 6 parameters (table 1).

Table 1

Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale used in the study

| Patient scale | Observer scale |

|---|---|

| 1. Pain | 1. Vascularization |

| 2. Pruritus | 2 Pigmentation |

| 3. Colour | 3. Thickness |

| 4. Thickness | 4. Surface area |

| 5. Irregularity | 5. Relief |

| 6. Stiffness | 6. Pliability |

Each parameter is scored on the same polytomous 10-point scale, in which a score of 1 indicates a scar comparable to ‘normal skin’ and a score of 10 reflects the ‘worst imaginable scar’. All the parameters are summed up to get the final score which ranges from 12 to 120 [18]. Clinical photographs were obtained at the baseline and subsequently at 3-week intervals, for up to 6 sessions.

Intervention

After the initial work-up, patients were allocated into two groups (Group A and Group B). Randomization was performed using the chit-in-a-box method.

Group A: Patients were administered intralesional triamcinolone acetonide available in vials containing 40 mg/ml solution. The site of the scar was first cleansed with isopropyl alcohol and then infiltrated with 2% lignocaine. Forty mg/ml (40 mg/ml) of triamcinolone acetonide was taken in a tuberculin syringe and was administered circumferentially into the scar from its borders (till blanching) with an interval of 1 cm between each injection. Maximum volume per treatment session was restricted to 3 ml. Treatment was repeated at an interval of 3 weeks up to 15 weeks or clinical resolution, whichever was earlier.

Group B: Patients in this group were administered intralesional bleomycin after performing the intradermal drug hypersensitivity test. These injections are available in vials containing 15 IU lyophilized powder. The powder was first diluted with 5 ml sterile water to prepare the stock solution (15 IU/5 ml). One part of 2% lignocaine and one part of bleomycin stock solution was taken in a tuberculin syringe to reach a final concentration of 1.5 IU/ml. The scar and the adjacent skin was first cleansed with isopropyl alcohol. Then fresh solution was injected intralesionally from the border of the scar targeting its deepest part. The solution was injected till blanching of the scar. Maximum volume per treatment session was restricted to 3 ml. Injections were administered regularly at 3 weeks’ interval with maximum of 6 sessions or until resolution, whichever was earlier.

Assessment

Patients were assessed objectively by the investigators using Physician Global Assessment at baseline and every 3 weeks during the study period. Response to treatment was evaluated by calculating POSAS in all patients at baseline and before each session for up to 3 weeks after the end of treatment. Reduction in the score of each patient and percentage reduction of baseline POSAS was calculated (table 2).

Table 2

Improvement in baseline POSAS scores

| Percentage reduction (%) | Grade |

|---|---|

| 0–25% | Poor |

| 26–50% | Fair |

| 51–75% | Good |

| > 75% | Excellent |

All the immediate and late adverse effects were evaluated after each treatment session.

Statistical analysis

All the data was compiled and tabulated in MS Excel and analysed with Statistical package for the Social Science (SPSS) software, version 24. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and discrete variables as percentages. χ2 test and Fisher exact test was used for comparison of categorical data. Paired t-test was used for intra-group comparison of parametric data and independent student t-test was used for inter-group comparison of two independent parametric samples. P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

A total of 4 patients discontinued the study (2 from Group A and 2 from Group B), resulting in 166 patients completing the study. The basic demographic characteristics of the patients is presented in table 3. Patients in the age group of 16–60 years were included in the study with majority of them belonging to the age group of 16–30 years (57.6%). Mean age in Group A and Group B was 30.4 ±9.3 and 31.9 ±10.4 years, respectively. A total of 76 (44.7%) males and 94 (55.3%) females were included in the study. Scar characteristics is presented in table 4. Approximately 80.6% of patients were diagnosed with keloids and 19.4% of patients with hypertrophic scars. Most (57.6%) of the patients had a single scar at presentation. The number of scars were comparable between both groups (p = 0.876). The duration of scars varied from 2 months to 18 months with the majority of them presenting for 7–12 months (53.5%). The majority (40%) of scars were present over the chest region in midline. A triggering event was reported in 51.2% of patients, with accidental trauma being the most frequent cause (35.9%).

Table 3

Baseline demographic characteristics of the study population

| Parameter | Group A (n = 85) | Group B (n = 85) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Age [years] | 18–30 | 51 | 60 | 47 | 55.3 | 0.795 |

| 31–45 | 26 | 30.6 | 28 | 32.9 | ||

| 46–60 | 08 | 9.4 | 10 | 11.8 | ||

| Sex | Male | 36 | 42.4 | 40 | 47.1 | 0.537 |

| Female | 49 | 57.6 | 45 | 52.9 | ||

Table 4

Characteristics of the scar in patients

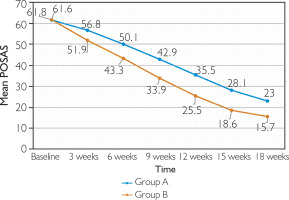

Mean baseline POSAS was 61.6 ±10.4 in Group A and 61.8 ± 8.2 in Group B (p = 0.922) (fig. 1). At 3 weeks, none of the patients achieved more than 50% improvement (good clinical response) in either group. Approximately 2.4% of the patients in Group A and 23.5% of the patients in Group B demonstrated a fair clinical response (25–50% improvement). At 6 weeks, 11.8% of the patients in Group B achieved a good clinical response, as compared to none of the patients in Group A. Poor response was seen in 61.9% of the patients in Group A and 4.7% of the patients in Group B.

At 9 weeks, 11.9% of the patients showed an excellent clinical response in Group B, as compared to none of the patients in Group A. Approximately 52.4% of the patients in Group B and 7.2% of the patients in Group A demonstrated a good clinical response (p = 0.0001). At 12 weeks, 49.4% of the patients in Group B and 2.4% of the patients in Group A showed an excellent clinical response (p = 0.0001). At 15 weeks, 90.4% of the patients in Group B and 26.5% of the patients in Group A showed an excellent clinical response (p = 0.0001).

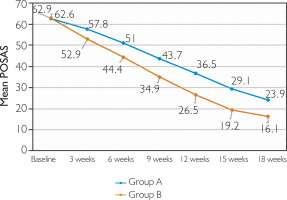

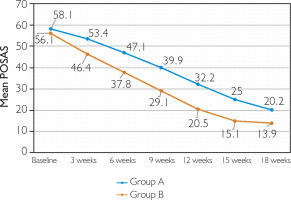

At 18 weeks, clinical response in Groups A and B was as follows: poor response in 4.8% versus none, fair in 1.2% in each group, good in 7.2% versus none, and excellent in 86.7% versus 98.8% (p = 0.014) (figs. 2, 3). With respect to the mean baseline POSAS score, a greater reduction was achieved by Group B as compared to Group A at the end of 18 weeks (p < 0.0001) (fig. 1). Response was similar irrespective of the scar type (p ≤ 0.0001 for keloids and hypertrophic scars separately) (figs. 4, 5).

Figure 2

Keloids in Group A demonstrating excellent clinical improvement (> 75% reduction in baseline POSAS score)

Figure 3

Keloid in Group B showing excellent clinical response (> 75% reduction in baseline POSAS score)

The treatment was effective (more than 50% reduction in baseline POSAS) in both groups. However, efficacy was higher in Group B as compared to Group A (98.8% vs. 93.9%; p = 0.09). On comparing the scars separately, hypertrophic scars demonstrated 100% efficacy in both groups (p = 1), while keloids demonstrated higher efficacy in Group B (although the result was comparable, with a p-value of 0.07). Within the groups, treatment was comparable for both scar types (p = 0.58 and p = 1 for Groups A and B, respectively) (table 5).

Table 5

Number of patients achieving POSAS 50 at week 18

| No. | Type of the scar | Group A (n = 83) | Group B (n = 83) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| 1. | Keloid | 59 | 89.4 | 69 | 98.6 | 0.07 |

| 2. | Hypertrophic scar | 19 | 100 | 13 | 100 | 1 |

| P-value | 0.58 | 1 | ||||

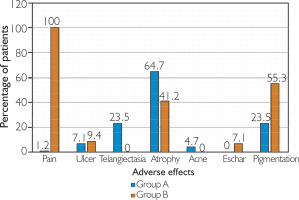

The most common adverse effect noted in Group A was atrophy of the surrounding skin (64.7%), followed by hypopigmentation and telangiectasia (23.5% each). In Group B, post-procedure pain was present in 100% of the patients, followed by hyperpigmentation (55.3%) and atrophy (41.2%). Post-procedure pain was significantly more common in Group B (p < 0.0001), whereas ulcer formation was comparable between both groups (p = 0.577). Eschar formation (7.1%) was limited to Group B, whereas telangiectasias (23.5%) and acneiform eruptions (4.7%) were seen in Group A (fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

Wound healing is a multifaceted biological process involving the coordinated activity of multiple cell populations. It is characterised by three overlapping phases: inflammation, proliferation and remodelling. Abnormal wound healing in certain individuals results in varied presentation of scarring with elevated scars representing only a part of this spectrum. Scars presenting as tissue elevations above the surrounding skin include both keloids and hypertrophic scars. Although benign in nature, these lesions cause cosmetic disfigurement and physical impairment leading to significant distress and decreased quality of life in patients [19].

Prevention remains the cornerstone in the management of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Essential measures include avoiding incisions in predisposed regions (e.g., presternal area, incisions crossing joint spaces), performing wound closure under minimal tension, and selecting appropriate suture materials [20]. With advances in technology, a wide array of therapeutic modalities has been developed. Current treatment options encompass topical, intralesional, and systemic pharmacotherapy, surgical excision, pressure and silicone dressings, laser therapy, radiotherapy, and cryotherapy [10]

Intralesional therapy allows for targeted drug delivery and enhanced tissue penetration, thereby increasing therapeutic efficacy. Several agents have been administered via this route. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide has demonstrated efficacy at concentrations from 10 up to 40 mg/ml, although its use is associated with a range of adverse effects [12]. Currently we are still in search of an ideal therapy for these lesions which has good efficacy with tolerable side effects and low rate of recurrence.

This forms the basis of continued research for new treatment modalities in the management of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Bleomycin, a cytotoxic agent traditionally employed in the treatment of various malignancies, has recently been investigated for its efficacy in the intralesional management of keloids and hypertrophic scars [21].

This study was done to compare the clinical efficacy and adverse effect profile of intralesional triamcinolone and intralesional bleomycin in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars.

We recruited 170 patients of keloids and hypertrophic scars in the age group of 16–60 years. The majority of patients belonged to the age group of 16–30 years. Higher prevalence in this age may be partly attributed to the fact that younger individuals are more prone to trauma and they have more elastic fibres in their skin which results in greater tension. Additionally, collagen synthesis is increased in this population. The mean age of patients was 30.4 ±9.3 years (mean ± SD) in Group A and 31.9 ±10.4 years (mean ± SD) in Group B. Abedini et al. [22] in 2014 included 50 patients of keloids and hypertrophic scars in the age group of 18–62 years. The calculated mean age was 30.26 ±10.59 which is consistent with our study. A similar observation was also seen in the study by Khan et al. [18] with a mean age of 33 ±10.12 years (mean ± SD) in Group A and 32 ±12.77 years (mean ± SD) in Group B.

Out of 170 patients enrolled, 76 (44.7%) were males and 94 (55.3%) were females with male to female ratio of 0.80:1. This finding was consistent with studies by Naeini et al. [23] and Khan et al. [18], which reported a higher prevalence of females compared to males. High proportion of females may be due to their higher cosmetic concern as compared to males.

A total of 80.6% of patients had keloids (137/170). This observation was consistent with the study conducted by Bodokh and Brun [24] where 86.1% of patients had keloids (31/36). Although a definitive consensus on incidence is lacking, most studies indicate that hypertrophic scars occur more frequently than keloids. Since this study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital, most post-surgical hypertrophic scars were managed within the surgical outpatient department. This may be a possible explanation of the higher proportion of keloids in our study.

Out of 170 patients, 98 (57.6%) patients presented with a single scar followed by 2 scars in 51 (30%) and multiple (> 2) scars in 21 (12.4%) patients (table 4). A similar observation was seen in the study conducted by Garg et al. [25] where the majority (72%) of the patients had a single keloid. Positive family history is strongly associated with multiple scars at different anatomical sites. The majority of patients in our study had no familial tendency for scar formation, which may be a possible explanation of the above observation.

Among the study population, 91 of 170 (53.5%) patients presented with scars of 7–12 months’ duration (table 4). The mean duration in Group A was 8.2 ±3.5 months while in Group B it was 8.8 ±3.7 months. These findings align with the study by Garg et al. [25], in which most patients presented with scars of less than 12 months’ duration, with a median duration of 8 months. The majority of patients initially pursue overthe-counter interventions to manage pain and pruritus, symptoms that are particularly pronounced during the early stages of scar development. This may explain the delayed presentation of patients.

The chest was the most common site of scars in this study (68/170; 40%) (table 4). This was consistent with the study conducted by Garg et al. [25] and Ahuja and Chatterjee [26]. High skin tension over the pre-sternal region predisposes to a higher incidence of scars in this region.

Out of 170 patients, 87 (51.2%) had a positive history of predisposing factors. No cause was identified in 48.8% of patients. Among the identified etiological factors, accidental trauma was the most frequent (61/170; 35.9%), followed sequentially by surgical procedures, burns, piercings, infections, and tattoos (table 4). Khalid et al. [27] reported that most scars in their cohort were attributable to trauma, piercings, or burns. Many minor injuries remain clinically unrecognized by patients, resulting in an undetermined etiology for the majority of cases in the present study.

Four patients (2 men and 2 women) discontinued the study; one due to inadequate therapeutic response and three due to intolerable adverse effects. Consequently, a total of 166 patients completed the study, with 83 participants in each group.

In terms of the mean value of POSAS, there was a decline from 61.6 ±10.4 at baseline to 23 ±10.2 at week 18 in Group A (mean total improvement = 62.7%, p = 0.0001) while in Group B the mean value changed from 61.8 ±8.2 to 15.7 ±4.9 (mean total improvement = 74.6%, p = 0.0001). When compared to Group A, a greater reduction in mean POSAS was demonstrated by Group B at each visit, which was significant (fig. 1). The results were consistent with the study conducted by Kabel et al. [28] with a mean total improvement of 73% in the bleomycin group. Efficacy of treatment was evaluated as fifty percent reduction in baseline POSAS (POSAS 50) at the end of 18 weeks. Group B demonstrated better efficacy with 98.8% of patients achieving POSAS 50 at the end of treatment as compared to 93.9% in Group A. However the p value came out to be 0.09 suggesting a comparable response (table 5). Khalid et al. [27] demonstrated an efficacy of 49% in the triamcinolone group (Group A in our study). The reason for low efficacy in their study may be due to lower concentration of the drug used (10 mg/ml) and different criteria for considering the treatment efficacious.

Treatment response was also assessed separately for keloids and hypertrophic scars. For both keloidal and hypertrophic scars, reduction in the mean value of POSAS was significantly better at each treatment session in Group B. For keloidal scars, there was a decline from 62.6 ±10.3 at baseline to 23.9 ±11.3 at week 18 in Group A (mean total improvement = 61.8%, p < 0.00001) while in Group B the mean value changed from 62.9 ±8.4 to 16.1 ±5.2 (mean total improvement = 73.1%, p < 0.00001) (figs. 4, 5). This was consistent with the study by Khan et al. [18] where mean total improvement in POSAS for keloidal scars was 62.2% in the triamcinolone group and 71.4% in the bleomycin group. On comparing treatment efficacy, 89.4% of keloids in Group A and 98.6% in Group B achieved POSAS 50 (p = 0.07) whereas 100% of hypertrophic scars in both the groups achieved POSAS 50 (p = 1) (table 5). The observation suggests that the efficacy was comparable between both the groups irrespective of the scar type. In a study conducted by Khalid et al. [27], triamcinolone (Group A in our study) was efficacious in 44.1% of keloids and 58.8% of hypertrophic scars.

No major adverse effects were observed in our study (fig. 6). Post-procedure pain was more common in Group B (100% versus 1.2% in Group A; p < 0.0001). In Group A, pain was mainly due to injecting the drug under pressure and subsided within 1–2 h without treatment whereas in Group B pain persisted for approximately 48–72 h and the majority of the patients required analgesics. Huu et al. [29] and Khan et al. [18] also observed similar results with 100% of patients experiencing pain with intralesional bleomycin. Ulcer formation was comparable in both groups with a p-value of 0.577. High dose and superficial injection technique may be the cause for this observation. Cutaneous atrophy as an adverse effect was observed more commonly with Group A as compared to Group B (64.7% vs. 41.2%; p = 0.002). Triamcinolone gets deposited locally due to its slow absorption from the injection site. This effect is further potentiated by using higher concentration (40 mg/ml) which results in increased frequency of cutaneous atrophy seen in Group A. Acneiform eruptions (4.7%) and telangiectasias (23.5%) were limited to Group A while eschar formation (7.1%) was seen in Group B. Patients with previous history of acne were more prone to develop acneiform eruptions. Eschar formation in Group B did not affect the patient significantly, shedding off within 2–3 weeks without intervention. In terms of pigmentary changes, 23.5% of patients in Group A developed hypopigmentation. The exact mechanism underlying hypopigmentation remains unclear, but it is thought to result from a reduction in melanocyte number and activity. A study by Khan et al. [18] reported telangiectasias in 21% of the patients and hypopigmentation in 29%, which is in concordance with our study. In Group B, 55.3% of the patients developed hyperpigmentation. This was consistent with the study by Huu et al. [29] where 56.7% of the patients noted hyperpigmentation.

CONCLUSIONS

Cutaneous scarring represents a significant clinical concern. Elevated scars encompass a spectrum, ranging from linear hypertrophic scars at one extreme to extensive keloids at the other. Compared to hypertrophic scars, keloids are generally more problematic due to their tendency to progressively enlarge over time. Besides this, they are more resistant to treatment and exhibit a higher relapse rate. Various therapeutic modalities include topical preparations, intralesional injections, silicone gel sheeting, surgical excision and lasers etc. Despite such diversity in the treatment options, these scars are notorious for their recurrence. Intralesional technique of drug delivery was introduced to overcome the disadvantage of penetrability seen with topical therapy.

Our study concluded that both the drugs have comparable efficacy in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars, achieving > 50% reduction in baseline POSAS at the end of treatment (p = 0.09). When comparing the side effect profile, the bleomycin group was associated with a cosmetically better outcome as there were no steroid-related side effects e.g. telangiectasia, acneiform eruptions etc. It should be considered over triamcinolone when costeffectiveness is not a limiting factor. Considering the possibility of major adverse effects, it should be used cautiously. More studies with larger sample size are required to assess the superiority of bleomycin over triamcinolone acetonide.