INTRODUCTION

The development of modern antipsoriatic therapies, including biologic drugs with different mechanisms of action, significantly improved outcomes, and redefined therapeutic goals in patients with plaque psoriasis. They were first officially defined in 2011 by the European Working Group and introduced into daily clinical practice [1, 2]. At the time, therapy success was defined as achieving at least a 75% reduction in Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) score (PASI 75) or even smaller improvement in PASI score from baseline, but at least 50% (PASI 50), with accompanying appropriate improvement in the quality of life expressed by a reduction in the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score to 5 points or lower [1, 2]. Since the consensus was developed, the number of biologic drugs available for systemic treatment has gradually increased, and progress in therapy has led to establishing of more restrictive therapeutic goals (e.g. achieving PASI 90 or even PASI 100) [1–3]. Current European guidelines for the systemic treatment of plaque psoriasis emphasize not only the percentage improvement in skin lesions indices as the therapeutic goal, but also the target absolute scores of indices assessing the severity of psoriasis, such as a PASI score ≤ 2 points, DLQI < 2 points, or achieving clear or almost clear skin in the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) [2]. The Diagnostic and Therapeutic Recommendations of the Polish Society of Dermatology (PTD) for the treatment of plaque psoriasis follow European guidelines, setting the therapeutic goal as full (or almost full) control of disease symptoms, i.e. full resolution of skin lesions. Experts emphasize that if this goal is not achievable due to significant baseline disease severity, treatment can be considered successful if the patient achieves at least PASI 90 or possibly PASI 75 accompanied by a significant improvement in quality of life, i.e. reduction in the DLQI score to ≤ 5 points [3]. A summary of PTD therapeutic goals in patients with plaque psoriasis is presented in table 1.

Table 1

Therapeutic goals in patients with plaque psoriasis according to PTD Diagnostic and Therapeutic Recommendations [3]

The recommendations place great emphasis on assessing the improvement of the patient’s quality of life. It has been proven that this improvement depends largely on drug effectiveness in terms of skin lesions recovery. Patients achieving PASI 90 have a greater chance of normalizing their quality of life compared to patients with PASI 75 [3]. There is evidence that biologic drugs can significantly improve the quality of life of psoriasis patients compared to other systemic therapies, especially since they are also highly effective in patients with nail lesions or psoriatic lesions in so-called special locations, such as the scalp or palms and soles [4–6].

In patients’ opinion, important or very important elements of psoriasis therapy include confidence in the therapy used, regaining disease control, or lack of fear of disease getting worse. A significant proportion of patients highly value the ability to lead a normal life [7]. Moreover, in chronic diseases such as psoriasis, which is lifelong, the long-term effectiveness and safety of therapy are also extremely important [8]. It is worth emphasizing that psoriasis is associated with a significant physical, psychological, social and economic burden, the cumulative effect of which may adversely impact the patient’s ability to reach his or her own “full life potential”. It is crucial that the expected therapeutic effect of a given drug maintains for as long as possible, with simultaneous good tolerance.

This article discusses selected issues related to efficacy and safety of biologic drugs in the treatment of patients with psoriasis, emphasizing the place of biosimilars in the management algorithm.

BIOLOGIC DRUGS, INCLUDING BIOSIMILARS, FOR THE TREATMENT OF PLAQUE PSORIASIS

Systemic treatment of plaque psoriasis includes phototherapy (UV therapy: UVB, PUVA) and pharmacotherapy, including small-molecule synthetic drugs and biologic drugs. Biologic drugs target the selected stage of the immune response; therefore, they show a more selective therapeutic effect than classic antipsoriatic drugs such as methotrexate, cyclosporin A or aztrethin [9].

Etanercept, a fusion protein, was the first biologic drug from the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors group approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2004 for the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [2, 10]. Subsequently, more TNF alpha inhibitors were registered, followed by gradually emerging drugs with other mechanisms of action (interleukin inhibitors: IL-12/IL-23p40, IL-17 and IL-23p19) [2, 10].

Table 2 shows the current list of biologic drugs registered in the European Union (EU) for the treatment of patients with plaque psoriasis, along with the year of registration, information on available biosimilars, and the presence of these molecules in the current drug program for the treatment of plaque psoriasis (B.47, as of March 2023) [2, 10–13].

Table 2

Biologic drugs approved in the European Union (with the year of approval indicated in brackets). Medications reimbursed under the B.47 drug program (as of March 2023) are marked in bold; data current as of August 2024

There are 4 biologic drugs for which biosimilars have been registered in the EU (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and ustekinumab). According to the EMA’s definition, biosimilar is a biologic drug that shows high similarity to the reference drug already on the market [14]. Biosimilars may be marketed by authorized entities once the reference product’s market exclusivity has expired. Biosimilars receive marketing authorization based on the same strict standards of quality, safety and efficacy that apply to all other drugs. The clinical trials supporting biosimilars approval confirm that any differences between the reference drug and the biosimilar will not affect its safety and efficacy [14].

The goal of biosimilars registering is to increase access to biologic therapies for more patients. Since 2006, the EMA has approved a total of 86 biosimilar medicinal products across various therapeutic areas. Biosimilars are widely used in EU countries, which made it possible to collect data on their safety. By September 2022, the number of patient-years of therapy with biosimilars in Europe was 1 million [15]. According to a statement published in April 2023 by the Heads of Medicines Agencies (HMA) and EMA, once a similar is registered in the EU, it can be used interchangeably. This means that a biosimilar can be used instead of the reference medicinal product (or vice versa), or one bioequivalent drug can be replaced by another bioequivalent drug of the same reference product [16]. The introduction of more biosimilars to the market offers an opportunity to improve access to therapies considered the standard of care. In the UK, the introduction of biosimilars enabled changes in drug reimbursement in 2021 and expanded access to biologic therapies for additional 25,000 patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis not responding to conventional therapy [17, 18]. According to the recommendations of the Polish Society of Dermatology (2020), “[9] TNF inhibitors have been used in medicine for more than 20 years and should no longer be as innovative drugs, but as a therapeutic standard that should be available to all patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, preferably as part of treatment provided on an outpatient basis” [9].

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE CHOICE OF BIOLOGIC DRUGS IN THE ALGORITHM OF PLAQUE PSORIASIS THERAPY

According to the recommendations of the Polish Society of Dermatology, biologic therapy is indicated for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis not responding to other available therapies [9]. Because of its high efficacy and relatively low risk of side effects, biologic therapy should be commenced as early as possible and continued as long as the benefits outweigh the potential risks [9]. PTD recommendations do not prioritize the choice of a specific biologic drug, leaving this decision to the discretion of the attending physician. On the other hand, European guidelines highlight differences in the registered labels of individual biologic drugs. For example, adalimumab can be used as first-line treatment for naïve patients with moderate-tosevere psoriasis who are eligible for systemic therapy. In contrast, etanercept can be used in second or subsequent treatment lines after failure, intolerance, or contraindications to conventional therapy [2]. Table 3 presents drugs registered in first- and second-line treatment.

Table 3

Treatment lines consistent with labels of biologic drugs (alphabetical order)

Several factors influence the choice of therapy, including both medical related to the patient and non-medical related to the healthcare system:

- immune-mediated conditions, such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and multiple sclerosis (MS),

- other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, chronic heart failure (CHF), and persistent infections,

reproductive plans of both male and female patients,

nature of the patient's occupation (e.g., frequent travel),

patient preferences regarding dosing regimen and route of administration,

cost considerations.

A shared immunological and genetic background partially explains the observed epidemiological association between psoriasis and its related comorbidities (table 4) [19].

Table 4

Relationship between psoriasis and other diseases, modified from: Biologic and small-molecule therapies for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: focus on psoriasis comorbidities; BioDrugs. 2023, 37, 35–55. Published online 2023 Jan 2. doi: 10.1007/s40259-022-00569-z

The presence of concomitant diseases is one of the factors influencing the clinical decision regarding the choice of drug. Some treatments may have a beneficial effect on the course of comorbidities, while others can be neutral or even unfavorable [18]. European guidelines indicate which groups of biologic drugs, and which molecules are preferred or contraindicated in patients with selected comorbidities [2].

For example, in patients with concomitant PsA preferred drugs include: all TNF-a inhibitors, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, guselkumab, and risankizumab.

In patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab pegol or ustekinumab are the first choice drugs.

In patients with concomitant ischemic heart disease, it is recommended to use TNF-a inhibitors, ustekinumab or IL-17 inhibitors.

TNF-α inhibitors are contraindicated in patients with concomitant advanced heart failure (class III/IV according to the New York Heart Association [NYHA] classification). In this group of patients, biologic drugs targeting specific molecules other than TNF-α (IL-17, IL-23 and IL-12/23 inhibitors) can be used.

Jiang et al. suggest the use of different biologic therapies in individual treatment lines depending on the comorbidities (table 5 presents selected examples) [19].

Table 5

Selected examples of comorbidities with relevant lines of treatment with biologics (modified from Jiang et al.) [19]

THE PLACE OF ADALIMUMAB, ETANERCEPT AND INFLIXIMAB IN THE TREATMENT ALGORITHM FOR PLAQUE PSORIASIS

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody with the broadest label among currently available biologics used in patients with plaque psoriasis [20].

According to the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC), adalimumab (both reference drug and biosimilar) can be used in patients with:

rheumatoid arthritis (RA),

psoriatic arthritis (PsA),

axial spondyloarthropathies (axSpA), including ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthropathy (nr-axSpA),

juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA, including polyarthritis – from the age of 2 years, and tendinitis – from the age of 6 years),

plaque psoriasis in adults and in the pediatric population (age of 4 years and older),

Hydradenitis suppurativa in adults and adolescents (aged 12 years and older),

Crohn's disease in adults and children (age of 6 years and older),

ulcerative colitis (from the age of 6 years) and

non-infectious uveitis (from the age of 2 years) [20].

A wide range of registered indications allows adalimumab to be used in patients with plaque psoriasis and selected comorbidities.

The efficacy of adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis has been evaluated in clinical trials [20–22]. In the 3-year follow-up of REVEAL trial, the rate of PASI 90 was 59% after 100 weeks, and 50% after 160 weeks of continuous treatment [21]. Menter et al. [23] presented interim results of the ESPRIT pivotal study evaluating the long-term efficacy and safety of adalimumab in more than 6,000 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis (more than 23,000 patient-years of overall exposure to adalimumab). During the first 7 years of the study, more than 50% of patients achieved “clear skin” or “minimal lesions” on the PGA scale at each annual follow-up visit.

Adalimumab is distinguished by clinicians’ extensive experience in its use and its well-known and well-described safety profile. Burmester et al. [24] analyzed data on the long-term safety of adalimumab from 77 clinical trials in all registered indications, involving a total of nearly 30,000 patients. The safety profile of adalimumab was consistent with previous reports, and there were no new safety signals [24]. The results of a Cochrane meta-analysis [22] showed that none of the biologic drugs, including adalimumab, was associated with a higher risk of serious adverse events (SAEs) compared to the placebo group. The results of Strober et al. [25] analysis of real-world registry data on safety of adalimumab in the treatment of psoriasis patients are also consistent with a long-term safety profile reported in clinical trials.

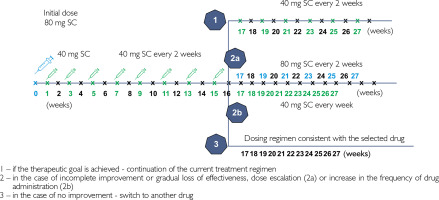

Adalimumab is administered subcutaneously (SC), with an initial dose of 80 mg, followed by 40 mg every 2 weeks, starting the first week after the initial dose (fig. 1) [20]. According to the SmPC, after 16 weeks, it may be beneficial to increase the dose to 40 mg SC every other week or 80 mg SC every 2 weeks in patients who have not sufficiently responded to adalimumab at a dose of 40 mg SC every 2 weeks. If sufficient response to such doses is achieved, it can then be reduced to the standard dose of 40 mg SC every 2 weeks [20].

Figure 1

Basic dosage regimen of adalimumab in adults with plaque psoriasis and two alternative regimens for adalimumab dose escalation in patients not responding to basic regimen within the first 16 weeks of therapy (according to SmPC)

In plaque psoriasis, adalimumab is typically used as monotherapy. There are data indicating that the combination of adalimumab with low-dose methotrexate (5–7.5 mg/week) in patients with plaque psoriasis and/or PsA may reduce the formation of antidrug antibodies, helping to improve the efficacy of adalimumab in patients with secondary worsening of treatment response [2, 9]. In such cases, patients require closer monitoring due to a potentially higher risk of infectious complications [9].

The most commonly reported adverse events of adalimumab are [20]:

infections (nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, and sinusitis),

injection site reactions (erythema, itching, hemorrhage, pain, or swelling),

headaches,

musculoskeletal pain.

These events are rated as very common, i.e., occurring in ≥ 1/10 patients.

Fatal and life-threatening infections (including sepsis, opportunistic infections, and tuberculosis), hepatitis B virus reactivation, and malignancies (including leukemia, lymphoma, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma) have also been reported in patients receiving adalimumab. The list of potential adverse effects reported during treatment with adalimumab is present in the current prescribing information of medicinal products including this molecule [20].

Dermatologists may be alerted regarding two potential adverse effects of TNF-α inhibitors, including adalimumab, namely the appearance or worsening of pustular psoriasis of the hands and feet (incidence from ≥ 1/100 to < 1/10 patients) and lupus-like syndrome (incidence from ≥ 1/10,000 to < 1/1,000 patients; a positive test for autoantibodies, including antibodies against double-stranded DNA, occurs frequently, i.e. from ≥ 1/100 to < 1/10 patients) [20].

The appearance of new psoriatic lesions in a patient treated for another disease or the worsening of existing psoriatic lesions as a result of the therapy is called paradoxical psoriasis. This effect has been noted after treatment with TNF-α inhibitors (most often infliximab), but also after the use of other biologic drugs. Clinically, paradoxical psoriasis related to TNF-α inhibitors manifests itself by the appearance of psoriatic plaques in various locations and pustular lesions on the hands and feet. Paradoxical psoriasis more often affects women and patients with nonspecific inflammatory bowel diseases. It can develop at various times after starting treatment (on average after about 11 months of therapy) [26].

Anti-TNF-induced lupus (ATIL) is a well-documented adverse event. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus usually occurs after the use of TNF inhibitors, with anti- SSB/Ro and anti-SSN/La antibodies being the most common serological markers. Among drug-induced lupus cases, anti-TNF antibodies are currently the main causative agents [27]. The summary of product characteristics for medicinal products containing adalimumab indicate that lupuslike syndrome occurs rarely (i.e., with a frequency of ≥ 1/10,000 to < 1/1,000 patients). Furthermore, in the pivotal studies with adalimumab, no patient with lupus-like syndrome developed lupus nephritis or central nervous system symptoms [20].

Etanercept, the first TNF-α inhibitor approved by the EMA for use in psoriasis, is a recombinant fusion protein that consists of a dimeric soluble TNF receptor 2 and the Fc fragment of a human IgG1 antibody. Etanercept neutralizes only the soluble anti-TNF fraction. Unlike other TNF inhibitors, it does not block the receptor-bound tumor necrosis factor. This may affect the safety and efficacy profile of this drug in various inflammatory diseases. The reference etanercept and the biosimilar can be used to treat the following diseases [28]:

RA,

JIA (from the age of 2 years in polyarticular and advanced oligoarticular JIA; from the age of 12 years in psoriatic arthritis and enthesitis),

psoriatic arthritis (PsA),

axial spondyloarthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis [AS] and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthropathy),

psoriasis vulgaris in adults and children and adolescents (from the age of 6 years).

In psoriasis patients etanercept is registered for use in adults with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis who have failed to respond to, or who have a contraindication to, or who are intolerant to other systemic therapies, including cyclosporine, methotrexate, or psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA). In the pediatric population, etanercept can be used in children and adolescents from the age of 6 years with severe plaque psoriasis who are inadequately controlled by, or are intolerant to, other systemic therapies or phototherapies [28].

Etanercept is administered by subcutaneous injections. Three dosing regimens are available for the treatment of adults with psoriasis. Two standard regimens, in which a dose of 25 mg etanercept twice weekly or a dose of 50 mg once weekly is administered from the beginning of therapy, and one alternative regimen, in which a higher dose of etanercept (50 mg twice weekly) is used for the first 12 weeks, followed by etanercept at one of the standard doses (table 6) [28].

Table 6

Etanercept dosage for adults with plaque psoriasis [28]

The efficacy of etanercept expressed as PASI 75 is estimated at 47% in week 12 and 59% in week 24 of therapy. The first effects should be expected between weeks 4 and 8 of treatment [9].

Etanercept is characterized by low immunogenicity, which may potentially affect the efficacy and safety of therapy. The frequency of the development of antibodies against etanercept in all indications ranges from 0 to 13%, and in plaque psoriasis from 2 to 5% of patients [29].

According to the summary of product characteristics, the most frequently reported adverse effects of etanercept include [28]:

injection site reactions (including pain, swelling, itching, erythema, and bleeding at the injection site) – very common ≥ 1/10 patients,

infections (upper respiratory tract infections, bronchitis, cystitis, and skin infections) – very common ≥ 1/10 patients,

headache – very common ≥ 1/10 patients.

Infliximab is a chimeric mouse-human IgG monoclonal antibody with high affinity for both soluble and transmembrane TNF forms [9]. According to the label, the reference and bioequivalent infliximab can be used in patients with [30]:

RA,

PsA,

plaque psoriasis in adults,

ankylosing spondylitis,

CD in adults and in the pediatric population (aged 6 years and older),

ulcerative colitis in adults and in the pediatric population (aged 6 years and older).

In clinical practice, infliximab has been used in patients with plaque psoriasis for two decades (this molecule was registered for this indication in 2005). Infliximab is a therapeutic option for adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis who have not achieved expected improvement with treatment, have contraindications to, or are intolerant to other systemic treatment regimens including cyclosporine, methotrexate, or PUVA. Due to the range of registered indications and proven efficacy, infliximab may be the first choice in patients with plaque psoriasis and concomitant inflammatory bowel disease [2, 30].

In psoriatic patients infliximab is used in combination with methotrexate, which is expected to reduce the immunogenicity of the biologic, including the development of neutralizing antibodies. Combination therapy requires increased vigilance and monitoring of patients for the risk of infection [9]. The data on the efficacy of infliximab in the treatment of patients with plaque psoriasis are very favorable. In the Cochrane meta-analysis, infliximab is listed as one of the biologics with the highest clinical efficacy in terms of improving PASI 90 (together with biologics with mechanisms of action other than TNF inhibition, i.e., bimekizumab, ixekizumab, and risankizumab) [22].

In psoriatic patients infliximab is administered as an intravenous infusion at a dose of 5 mg/kg body weight. Subsequent infusions of 5 mg/kg body weight should be administered 2 and 6 weeks after the first infusion, and then at 8-week intervals thereafter [30, 31]. In the European Union, a bioequivalent subcutaneous infliximab is approved for maintenance treatment in plaque psoriasis at a dose of 120 mg every 2 weeks, following induction therapy with an intravenous form [31].

In clinical trials, the most commonly reported adverse reaction with infliximab was upper respiratory tract infection, which occurred in approximately 25% of patients. The most serious adverse reactions reported with infliximab include HBV reactivation, congestive heart failure, serious infections, serum sickness, hematologic reactions, systemic lupus erythematosus or lupus-like syndrome, demyelinating disorders, hepatobiliary events, lymphoma, HSTCL, leukemia, Merkel cell carcinoma, melanoma, childhood malignancies, sarcoidosis or sarcoid-like reaction, intestinal or perianal abscess (in CD), and serious infusion reactions [30, 31].

THE PLACE OF USTEKINUMAB IN THE ALGORITHM OF PLAQUE PSORIASIS TREATMENT

Ustekinumab was the next biologic drug registered in Europe after TNF-α inhibitors in 2009, approved for the treatment of plaque psoriasis [2].

Ustekinumab is a human monoclonal antibody that binds with high specificity to the p40 protein subunit of human interleukins 12 and 23 (IL-12 and IL-23). Ustekinumab inhibits the biological activity of these cytokines by preventing p40 from binding to the IL-12Rβ1 protein receptor located on the surface of immune cells [32].

According to SmPC, ustekinumab is registered for use in adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis not responding to treatment or with contraindications or intolerance to other systemic therapies including cyclosporine, methotrexate or PUVA. Ustekinumab is also registered for the treatment of pediatric patients aged 6 years and older with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with inadequate response or intolerance to other systemic therapies or phototherapy. Ustekinumab is also registered for the treatment of adult patients with PsA with inadequate response to current treatment with non-biologic disease-modifying drugs [32].

All doses of ustekinumab in the treatment of psoriasis and PsA are administered subcutaneously (SC). The single dose of the drug in these indications depends on the patient’s body weight (table 7). In adult patients with body weight up to 100 kg, a dose of 45 mg SC is used (at week 0, after 4 weeks, and every 12 weeks thereafter). In adult patients with body weight over 100 kg, a dose of 90 mg SC is used (at week 0, after 4 weeks, and every 12 weeks thereafter) [32, 33].

Table 7

Ustekinumab dosage regimen for patients with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA applies only to adults) according to SmPC [32, 33]

| Patient | Body weight | Initial dose – day 0 | After 4 weeks | Every 12 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | ≤ 100 kg | 45 mg SC | 45 mg SC | 45 mg SC |

| > 100 kg | 90 mg SC | 90 mg SC | 90 mg SC | |

| Pediatric population | < 60 kg | Appropriate dose based on body weight* | Appropriate dose based on body weight* | Appropriate dose based on body weight* |

| ≥ 60 ≤ 100 kg | 45 mg SC | 45 mg SC | 45 mg SC | |

| > 100 kg | 90 mg SC | 90 mg SC | 90 mg SC |

* Injection volume (ml) for patients with body weight < 60 kg should be calculated according to the following formula: body weight (kg) × 0.0083 (ml/kg) or determined based on the table in Stelara SmPC [33]. Patients with body weight < 60 kg should receive appropriate doses using the ustekinumab 45 mg solution for injection in vials, which allows for weight-based dosing. Only patients with body weight of at least 60 kg should receive a dose using the fixed-dose pre-filled syringe (45 mg or 90 mg) [32, 33].

Administering a biologic drug once every 3 months can be a convenient therapeutic option for many patients. Long intervals between doses can be important for patients with a fear of injections, as well as those who travel frequently. This therapy regimen allows the administration of the drug during hospital or clinic follow-up visits and reduces the possible challenges in the storage and transportation of biologics or biosimilars. The frequency of drug administration can also affect patient compliance. In a systematic review and meta-analysis by Piragine et al. [34], the highest adherence rates were reported for ustekinumab and the lowest for etanercept.

Ustekinumab is used in the treatment of plaque psoriasis as monotherapy [2, 9, 32]. No data are available to support the validity of combining ustekinumab with methotrexate to reduce anti-drug antibody formation [2]. Ustekinumab has relatively low immunogenicity [34, 35]. In the PHOENIX study with the reference drug, the percentage of patients who developed anti-drug antibodies was 4.9%; however, this phenomenon was not identified as a poor predictive factor [36]. Publications review by Strand et al. [29] indicate that the percentage of patients with positive anti-drug antibodies for ustekinumab ranged from 4% to 8.6%.

An important argument for using ustekinumab is its favorable safety profile. According to SmPC, the most common adverse reactions (> 5%) to ustekinumab in adult patients were nasopharyngitis and headache, mostly mild and not requiring treatment discontinuation [32, 33]. The most serious adverse reactions reported after ustekinumab use are severe hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis. A list of potential side effects of ustekinumab is present in the current drug product characteristics of this molecule [32].

Data published in 2020 from the BIOBADADERM, the Spanish Registry of Adverse Events Associated With Biologic Drugs in Dermatology indicated that ustekinumab and secukinumab had the best safety profiles among the drugs evaluated (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, ustekinumab, secukinumab, aztrethin, apremilast, cyclosporine, methotrexate) [37]. Real-world data from the UK BADBIR registry showed that guselkumab, ustekinumab and secukinumab were associated with similar therapy retention related to safety, with ustekinumab being superior to adalimumab and ixekizumab [38]. There is evidence confirming that the use of ustekinumab is associated with a lower risk of infectious complications compared to other biologic drugs, and ustekinumab could be a preferred therapeutic option in patients at high risk of infection [39]. An analysis of a cohort study based on patient databases showed that the use of other biologics and apremilast was associated with a 1.4- to 3-fold increased risk of hospitalization for serious infections in patients with psoriasis or PsA compared to ustekinumab [40]. Low immunogenicity and a good safety profile support choosing ustekinumab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. The authors also point to the choice of this drug in patients with burden, comorbidities (such as heart failure), demyelinating syndromes (such as multiple sclerosis), or elderly patients [41].

The long time that has elapsed since the EMA registration of ustekinumab means that long-term safety and efficacy data for the drug are now available, as well as information on therapy retention (known as “drug survival time”). After 5-year follow-up in the PHOENIX 2 study, 76.5% of patients achieved PASI 75 and 50% of patients achieved PASI 90, after 244 weeks of treatment with ustekinumab 45 mg SC [42]. Data published by Gönüal et al. [43] summarizing 6 years of experience with ustekinumab in patients with plaque psoriasis show that ustekinumab may be a therapeutic option for patients not responding to other therapies. According to the authors, the positive outcomes persist if the patient responds well to the first or second dose of the drug. The results of database analysis of patients with plaque psoriasis showed that ustekinumab was associated with lower discontinuation rates and higher retention and adherence rates compared to other therapies (adalimumab, apremilast, etanercept, secukinumab) [44]. The longest duration of maintenance treatment with ustekinumab compared to other molecules were also shown in an analysis of real-world data from the Swedish registry [45].

CONCLUSIONS

Systemic therapies are standard of care in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, and topical treatments can be only supportive care [2, 9]. Currently psoriasis is one of the incurable diseases, however, systemic drugs offer a chance to suppress the inflammatory process. Therefore, they not only improve skin lesions, which is expected by patients, but can also cause a systemic effect. There are data indicating that systemic drugs, including biologics, can slow down the atherosclerotic process accelerated by generalized inflammation and reduce the cardiovascular risk [46, 47].

Polish and European guidelines for the management of plaque psoriasis clearly define the timing of systemic treatment introduction, recommending the use of objective scoring systems to assess disease severity [2, 9]. The choice between molecules remains the decision of the attending physician, with active patient participation in discussing the treatment plan. Biologic drugs show a more selective therapeutic effect than classic antipsoriatic drugs [9]. The decision to use a particular molecule is influenced by a range of factors, including comorbidities, dosing regimen, but also the cost of therapy.

Since 2017, the EMA has accepted marketing authorization of additional biosimilars, registered for use in plaque psoriasis (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, ustekinumab). Biosimilars show a similar efficacy and safety profile to existing reference drugs [14, 15]. According to the EMA and the HMA statement, biologic drugs registered in the EU can be used interchangeably [16].

Table 8 summarizes the advantages of four drugs, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and ustekinumab, for which biosimilars are already registered.

Table 8

Summary of adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab benefits in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis