PURPOSE

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (THS) is a rare cause of painful ophtalmoplegia with an estimated annual incidence of 1 case per million in the general population [1]. The first case of a patient diagnosed with THS was described by Dr E. Tolosa in 1954 and since then numerous cases have been reported [2-5]. In 1988 the International Headache Society established the first diagnostic criteria for THS, which has evolved over the years [4]. According to the current diagnostic criteria included in the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3), THS is defined as a unilateral headache with ipsilateral paresis of at least one cranial nerve responsible for eye movement due to idiopathic granulomatous inflammation of periorbital areas [6]. Despite the many studies on THS, its underlying cause is still unknown [7]. The full diagnostic criteria in accordance with ICHD-3 are presented in Table 1. The authors would like to present a case series of six patients suffering from painful ophtalmoplegia, who were hospitalized in the same hospital in Warsaw in Poland and discuss the possible challenges in the context of THS diagnosis.

Table 1

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome diagnosis criteria according to the ICHD-3

CASE DESCRIPTION

The following cases involve six patients hospitalized in the Neurology Department of Bielanski Hospital in Warsaw due to painful ophtalmoplegia symptoms. The retrospectively analysed patients had been hospitalized between 2018 and 2022. Patient number 6 gave consent for visual content relating to their case to be published. The clinical features of our patients are presented in Table 2, whereas in Table 3 the results of laboratory and neuroimaging tests are shown.

Table 2

Clinical features and patients’ symptoms

Table 3

Neuroimaging and laboratory tests results

Case 1

During a period of three years, between the ages of 61 and 64, this woman suffered from four episodes of left-sided headache with ipsilateral eye movement impairment. The episodes were separated by headache-free periods that lasted, respectively, 22, 10 and 4 months. All four episodes had a similar manifestation of constant, severe pain localized on the left side of the forehead and in the left orbital region, behind the eyeball. The pain increased with horizontal eye movements and had a short response to simple analgesics. An inability to achieve complete abduction and adduction in the affected eye was observed. Additionally, during the first episode soft tissue swelling and slight exophthalmos were noted, and during the third episode the patient reported transient diplopia. There were no additional abnormalities during the neurological examination. In the medical history, the patient reported hypertension, coronary heart disease, lipid metabolism disorder and ischemic brain stroke. A blood test showed only a slightly elevated level of C-reactive protein (CRP), the rest of the blood tests were normal. Computed tomography (CT) with angiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (1.5 T, 3 mm thickness), performed during every single relapse, showed normal findings. The patient was treated with intravenous injections of methylprednisolone in the dose of 1,000 mg daily for 5 days, followed by oral steroid therapy of 40-60 mg of prednisolone in gradually decreasing doses (specified in Table 4). Prompt recovery was observed with complete relief of pain and symptoms.

Table 4

Applied treatment with observed effects

Case 2

A 56-years-old man was admitted to the hospital around 4 weeks after the first symptoms, consisting of double vision accompanied by severe periorbital pain on the left side. In later stages pain covered the entire half of the head on the same side. The neurological examination showed paresis of the left abducens nerve and slight weakness of the right upper limb (residual weakness after a cervical spine operation). All blood tests were normal. MRI of the brain and the eye sockets (1.5 T, 3 mm thickness) showed slight excess tissue in the cavernous sinus and blood blister-like aneurysms (BBA) on the internal carotid artery. The medical history of the patient showed hypertension and psoriasis. The patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone in the dose of 1,000 mg daily for 5 days. Oral steroid therapy was not implemented. The headache disappeared after 24 hours following the beginning of the treatment, followed by a full recovery over the next few days.

Case 3

An 82-years-old woman was admitted to the hospital due to a headache lasting for two weeks. The pain was localized in the left temporal-parietal area and behind the left eyeball. During the second week of the pain, double vision and ptosis of the left eyelid occurred. The pain had compressive characteristics and moderate intensity. The neurological examination showed paresis of the left oculomotor nerve. Blood tests did not show any abnormalities. MRI of the brain with angiography showed mucosal changes in the sphenoid sinus on the left side. The patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone of 1,000 mg daily dose for 5 days, followed by oral steroid therapy of 30 mg (prednisolone, over a total of 22 days). A rapid clinical improvement was observed after the treatment.

Case 4

A 65-year-old woman was examined due to severe pain in the right orbit lasting for one week. The day before her admission to the hospital, double vision occurred. Neurological examination revealed dysfunction of the right oculomotor nerve and the first branch of the trigeminal cranial nerve on the same side. The medical history showed obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM) type 2 (with normal glucose levels). Extensive blood and cerebro- spinal fluid (CSF) examinations showed normal results. MRI of the brain was normal. The introduction of pulse corticosteroid therapy (methylprednisolone, 0.5 g for 5 days – reduced doses due to DM) followed by oral steroid therapy (60 mg of prednisolone per day in gradually decreasing doses) reduced headache and decreased neurological deficits. Nearly one year later, the symptoms recurred on the other side of the patient’s head; she suffered from a severe periorbital headache with double and blurred vision. The neurological examination showed the pupil in the left eye to be dilated, with poor light response, partial ptosis and paresis of the left oculomotor nerve. There were no significant changes in the blood tests on admission to the hospital. The MRI of the brain was repeated and no abnormalities were found. Treatment with intravenous steroid therapy was started (5 days of 1,000 mg of methylprednisolone per day), with the rapid improvement of symptoms (the headache disappeared during the first 24 hours). On the fifth day of treatment, the patient reported pain in the right subclavicular region. The affected subclavicular area appeared reddened and warmer. Ultrasonography was performed that showed a possible abscess forming in the soft tissues of the painful area. Blood tests showed increased markers of inflammation (CRP, leukocytes). Antibiotics were administered empirically (clindamycine). Blood culture tests were performed which showed positive results and identified Staphylococcus aureus MSSA type, therefore antibiotic therapy was modified (with the addition of cefotaxime). On the tenth day of the hospitalization, a respiratory and circulatory failure occurred due to sepsis, which led to the death of the patient.

Case 5

A 40-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital due to a headache in the left orbital area with visual disturbances. The symptoms occurred 2-3 weeks before the patient was referred to the hospital. Two days before the hospitalization, double vision occurred. The patient was treated with antibiotics by her general practitioner (GP), who suspected sinusitis. The neurological examination showed left oculomotor paresis and slight paresis of the left abducens nerve. DM type 1 was reported in the patient’s medical history. During the hospitalization, hypertension was diagnosed. Blood tests were normal. MRI of the brain and the eye sockets were normal. The patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone in the dose of 1,000 mg daily for 5 days, followed by oral steroid therapy over 24 days (40 mg of prednisolone in gradually decreasing doses). Rapid improvement was observed after the therapy.

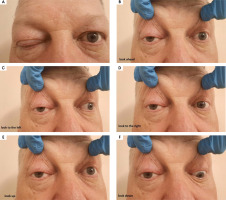

Case 6

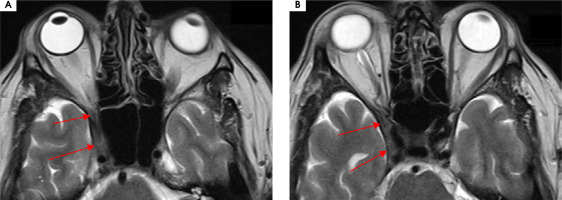

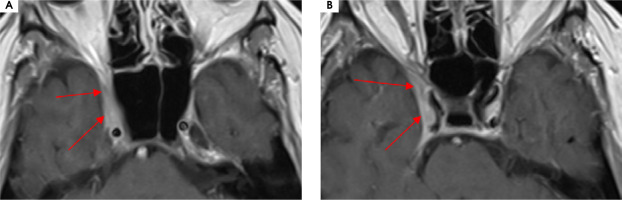

A 56-year-old man was admitted to the hospital due to double vision, a problem with the mobility of the right eyeball, and a right-sided headache. The first symptoms were not so obvious due to a prickly headache in the middle of the face, with swelling on its right side. Around 7-8 weeks later typical symptoms appeared, consisting of severe right-sided periorbital headache and ipsilateral eye movement disorder. In the meantime, the patient was treated with antibiotics by a dentist due to suspected peroidontitis. The neurological assessment showed ophthalmoplegia of the right eyeball, ptosis, and exophthalmos. The MRI findings showed asymmetrical reinforcement and thickening up to 6 mm within the cavernous sinus on the right side, laterally directed towards the superior orbital fissure and the top of the orbit. The MRI findings are shown in Figure I and Figure II. Treatment with intravenous steroid was started (1,000 mg of methylprednisolone daily for 7 days), with an improvement of the symptoms, followed by oral steroid of 60 mg of prednisolone in gradually decreasing doses over 36 days. The rapid clinical improvement was observed as shown in Figures III to VI. We also include a video showing the patient’s eye motor functions on the 7th day of the treatment.

Figure I

Patient number 6. Axial MRI T2 sequences showing asymmetrical thickening up to 6 mm within the right cavernous sinus, laterally directed towards the superior orbital fissure and the top of the orbit

Figure II

Patient number 6. Axial MRI T1 sequences with contrast showing asymmetrical reinforcement within the right caver nous sinus

PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

All the patients gave informed consent to diagnostic procedures and treatment. There were no major complaints, and adverse effects due to the treatment in each case are presented in Table 4. The only exception was the second episode of patient number 4, with the occurrence of severe adverse effects as described previously.

DISCUSSION

Although the ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for THS demand the confirmation of the inflammatory process via neuroimaging or biopsy, only two of our patients met this criterion [6]. Pathological effects may be absent in the neuroimaging tests due to technical limitations (e.g. resolution) or a too-early performance of MRI [8]. We chose not to perform a biopsy due to the high risk of exceeding the potential benefits for the patients. Likewise, numerous cases can be found in the literature of typical clinical manifestations of THS without confirmation of inflammatory process [8-10]. Approximately up to 50% of typical THS cases are reported without inflammatory findings in the neuroimaging within the typical areas (cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure or orbit) [9, 10]. Such cases are referred to as “benign THS”, as opposed to the inflammatory cases of the condition [8]. Other possible causes of painful ophtalmoplegia without abnormal neuroimaging findings include disorders such as DM polineuropathy or recurrent painful ophtalmoplegic neuropathy (previously classified as ophtalmoplegic migraine) [10]. Two of our patients had a previous history of DM, but we excluded this etiology due to normal glucose levels (at the fasting and 4-point profile). In the case of patient number 1, with four recurrent episodes, we did differentiate between THS and recurrent painful ophtalmoplegic neuropathy. We concluded that THS was more probable due to a good response to the steroid therapy.

High responsiveness to the steroid treatment was included in the previous diagnostic criteria of THS in both the first and second editions of the ICHD [11]. In the current third edition, steroid responsiveness was excluded from the THS criteria, but it is still mentioned as an additional factor supporting the diagnosis [6]. Most clinical reports support the high effectiveness of steroids in the treatment of THS [9, 12]. All our patients were treated with steroid therapy, after which their condition improved rapidly, especially when it came to the pain component. There were no significant adverse effects reported, except for patient number 4 (inflammation resulting in death). Comparably, Rodriguez et al. reported the case of a 57-year-old patient primarily misdiagnosed with THS with pathological findings within the cavernous sinus [13]. In this case a 3-day course of methylprednisolone was ineffective, followed by a worsening of the patient’s condition and resulting in death [13]. Post-mortem examination revealed actinomyces cavernous sinus infection [13]. This particular case is quite similar to the second episode of our patient number 4. The anti-inflammatory effect of steroids probably exacerbated the bacterial infection, resulting in the serious adverse effects of the therapy. Every day careful observation of the patient is a very important part of steroid treatment because new symptoms of infection can occur each day.

Unfortunately, many other disorders mimicking THS may also improve during the initial stages of steroid therapy (e.g. neoplasms) [2]. Mendonca et al. reported a case in which an initial diagnosis of THS was later revealed to be Eales disease during the follow-up [14]. Similarly, Brandy-Garcia et al. reported a case of a 55-year-old woman presenting THS symptoms, who was diagnosed with sarcoidosis after additional testing [15]. Both patients improved after the steroid treatment, which could lead to misdiagnosis. In each case of suspected THS, the treatment should be started very carefully and only after the exclusion of other pathologies. This is consistent with the last section of the THS diagnostic criteria, stating that the symptoms cannot be better accounted for by any other ICHD-3 criteria [6].

The initial findings of the laboratory tests performed on our patients did not show any significant abnormalities. Other studies confirm that blood test results stay within the normal range during THS episodes, while elevated inflammatory markers should be an alarming signal of other etiologies [7, 13]. A lumbar puncture was performed in three of our patients. Each time the opening pressure was within the normal range and no abnormalities were found in the basic analysis. Yang et al. performed a detailed cerebrospinal fluid analysis of 55 THS cases [16]. The study showed elevated protein levels in about 27% of the cases and oligoclonal antibodies were found in 29% of the patients. Intrathecal antibodies synthesis was statistically more frequent when THS symptoms lasted for less than 30 days, suggesting an active inflammatory process. The presence of oligoclonal bands can prove useful in future diagnostic approaches.

The period between the first eye movement disorders and the first headache symptoms in our patients varied between 0 to 55 days. According to the ICHD-3, this period should not be longer than 14 days in THS patients, as a confirmation of a temporal relation between the symptoms [6]. Two of our patients exceeded the time limit by 4 and 41 days respectively. However, we applied steroid therapy for both of them with good results. Not many researchers elaborate on this aspect, but there are reported cases of patients exceeding the period of 14 days and still being treated successfully with steroids [4].

Beside the involvement of the IIIrd, IVth and VIth cranial nerves in THS, there is always a possibility that additional cranial nerves are involved. The involvement of each cranial nerve varies between studies [7, 9]. There are reported cases involving the IIth, Vth, VIIth and VIIIth cranial nerves [6, 12, 17, 18]. In the case of the first episode of our patient number 4, the neurological examination showed dysfunction of the first branch of the trigeminal nerve ipsilateral to other symptoms. Furthermore, there are seldom bilateral THS manifestations (up to 5%) [19].

Mullen et al. concluded that THS diagnostic criteria are suboptimal, whereas Dutta et al. implied that THS should be renamed for a wider spectrum of clinical situations [2, 11]. Current diagnostic criteria leave a wide area for misdiagnosis, especially at the early stages of the disorder.

CONCLUSIONS

In the end, only one of the 6 patients analysed (patient number 2) met the full criteria for THS according to the ICHD-3. Nevertheless, all of them were treated successfully with the exact same steroid therapy. In our opinion, the key factor in the diagnostic process is the exclusion of other pathologies, rather than confirming idiopathic inflammation within periorbital structures. One of the most important factors regarding steroid treatment is its anti-inflammatory effect, which can exacerbate infections. We suggest a thorough and full examination of the patient before implementing steroid treatment and a careful follow-up for a potential misdiagnosis. Currently, there are neither specific biochemical (e.g., inflammatory) nor neuroimaging markers for THS diagnostics. Therefore further studies are needed, as well as a review of diagnostic criteria.