Introduction

As a basic strategy for improving health outcomes, the WHO resolution emphasizes the need for countries to develop and implement integrated, patient-centred health services. It encourages the adoption of national policies that prioritize complex and coordinated care across the continuum of health services, from primary to specialized care, while emphasizing the active participation of individuals, families, and communities in health decision-making. The resolution emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and partnerships, and seeks to strengthen the policy makers and the national health insurance structures to enable effective coordination at all levels. In addition, it highlights the need to organize inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients’ healthcare system, supported by targeted financing mechanisms and based on reliable data with digital tools to guide service delivery [1].

In its current form, the Polish healthcare system fails to provide such support to people with IBD – or does so in a way that is poorly integrated and coordinated [2], with limited use of modern digital tools (including m/eHealth solutions).

The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) conducted a web-based survey study of 4670 patients from 25 different European countries, of whom only 52% reported adequate access to care [3]. Although treatment options for ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) continue to expand and considerable funds are allocated toward its management, many patients still do not meet their therapeutic goals [4–7]. Recently, however, the ECCO stated that advanced therapy (accelerated step-up or sometimes top-down) should be used immediately from the time of diagnosis (especially in CD) [8]. In addition, care is often fragmented across multiple centres in different locations, depending on the patient’s awareness and capabilities, as well as the resources and expertise of the referring centre or medical staff. Furthermore, the quality of care received by patients can vary significantly [9]. These variations in practice suggest that healthcare delivery may not be fully optimized, potentially leading to poorer outcomes, including increased reliance on acute care services, higher rates of surgical intervention, higher rates of absenteeism and presenteeism, and a reduced quality of life among individuals with IBD [10]. Overall, the new model is an approach that ensures equitable, comprehensive, and high-quality care that is adapted to people’s needs, thereby improving accessibility, continuity, and overall efficiency of healthcare services.

IBD-related costs especially emergency department visits and hospital admissions continue to account for a substantial share of direct healthcare costs, despite recent therapeutic advances and the financial resources they require. In Poland, treatment is mainly provided within primary care and outpatient care. According to data from the Ministry of Health (Maps of Health Needs platform; MPZ), in 2021, patients with IBD received 139,000 consultations in primary care and 115,000 consultations in outpatient specialised care (AOS), with an additional 42,000 hospitalizations reported [11].

Notably, IBD primarily affects the working-age population, coinciding with periods of education and professional skill development. This is supported by data from the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS), which in 2021 recorded significant expenditures on incapacity for work among patients with CD (ICD 10: K50) and UC (K51). These costs amounted to PLN 32 million for CD and PLN 52 million for UC. On average, for both diseases, approximately 41% of the total ZUS expenditures were allocated to disability benefits, while 42% covered sickness absence [12].

This publication sets out to propose improved organisation of the approach to IBD care in Poland, based on established evidence and insights from leading international practices.

Main principles of comprehensive care

Epidemiological data, along with insights from the Polish healthcare system, clearly indicate that the current model of care for patients with IBD in Poland requires improvements in the quality of care – both in clinical management and in the organization of services (including their integration and continuity). Evidence from European countries suggests that the introduction of integrated care models in the management of IBD has many benefits – a multidisciplinary approach enables more comprehensive and personalised treatment, resulting in better health outcomes for patients, and the integration of care around a reference unit ensures continuity, minimises disruptions in care, and reduces the need for hospitalisation. In addition, patient-centred care and education allow for improved health awareness and disease management, which can lead to reduced relapse rates and better quality of life. This approach promotes the efficient use of healthcare resources, benefiting both patients and the healthcare system as a whole [13].

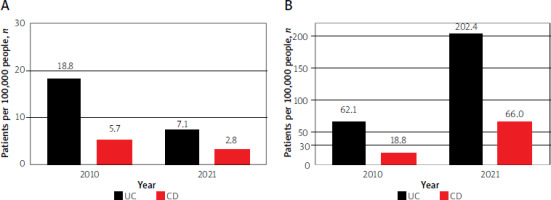

Data from the National Health Fund indicate that in Poland, in 2021, the number of patients with IBD was 102.22 thousand – 25.15 thousand with CD and 77.07 thousand with UC, corresponding to prevalence rates of 66 and 202.4 per 100,000 people, respectively (Figure 1). The highest prevalence of IBD was observed in the 30–44 years age group [14].

Figure 1

Annual incidence (A) and prevalence (B) recorded (NFZ) for Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)

To enhance the quality and coordination of care for IBD patients, a comprehensive care model has been developed. The proposed model acknowledges the potential for care to be delivered by gastroenterologists in collaboration with other specialists, including, notably, surgeons, dietitians, and psychologists. It also encompasses the involvement of additional specialists, such as rheumatologists, dermatologists, pulmonologists, ophthalmologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, cardiologists, microbiologists, histopathologists, gynaecologists and obstetricians, and radiologists, within outpatient care. The proposals include, among others, improvements in patient monitoring, including the routine measurements of calprotectin [14, 15], as well as the introduction of teleconsultations, including those in collaboration with primary care facilities. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and faecal markers, such as calprotectin or lactoferrin, can be used to guide therapy and facilitate short-term follow-up, and predict clinical relapse. Additionally, faecal calprotectin can help in differentiating IBD from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [16].

A fundamental aspect of the proposed model’s development involves establishing reference centres, with coordinators equipped to provide comprehensive care as a centre of excellence, in collaboration with other centres and primary care facilities (Figure 2). These changes could lead to increases in both the number of patients enrolled in drug programmes and their proportion among all IBD patients. According to data from the MPZ, the proportion of patients treated within the drug programme in 2021 was only 7.9% of all CD patients and 1.9% of all UC patients [17].

Figure 2

The main principles of the comprehensive model for inflammatory bowel disease patients in Poland

Additionally, the proposal entails the implementation of a digital solution, including the Polish patient registry. This will facilitate monitoring not only the treatment outcomes but also the quality of care.

Multidisciplinary teams providing care to patients with IBD should be established to ensure comprehensive care for patients, which should include [18]:

specialist doctors – at least a gastroenterologist (as the medical coordinator of care), a general surgeon, and a radiologist,

nurses with experience in the care of patients with IBD,

a dietitian,

a clinical psychologist,

a care assistant who also serves as an administrative support, who facilitates communication between team members, coordinates the patient visits, and is responsible for gathering information, scheduling diagnostic tests and consultations with specialists based on the individual IBD care plan, maintaining reporting records, and entering data into reporting systems, particularly in cooperation with primary care.

The team should be able to co-operate on an ongoing basis (required) with doctors from other specialties (either locally or by access), particularly rheumatologists, dermatologists, pulmonologists, ophthalmologists, gynaecologists and obstetricians, cardiologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, histopathologists and microbiologists. The scope of comprehensive care should primarily include the following elements:

Monitoring of patients through the creation of individual patient plans of care (IPOCs), which should be adjusted to the cooperation with primary care with opportunities for monitoring based on calprotectin assessment, drugs, and vaccinations;

Comprehensive advice to enable multidisciplinary cooperation, including psychologists, dietitians and nurses;

Enabling teleconsultation between the patient and the reference centre, and possibly in cooperation with the primary care or other health service providers;

Patient education to improve the ability to carry out an appropriate level of self-care, and care coordination, including collaboration with other professionals;

The establishment of an IBD registry or digital monitoring system to enable the ongoing clinical evaluation of this patient population, together with an assessment of the quality of care provided.

Health care service model

A fundamental component of care implementation is the conceptualisation of health services that, in particular, facilitate the access of diagnostics in the ambulatory care in line with the most recent clinical guidelines. The recommended model of comprehensive care aims to improve coordination and ensure continuity of care for patients both within and outside drug programmes, and increase safety, particularly in cases of exacerbations or treatment-related complications.

The implementation of this model involves the introduction of novel regulations for the financing of healthcare services by the NFZ, with a focus on addressing the needs of patients with IBD. The financing mechanism is envisaged to be based on multidisciplinary care teams, leveraging technology and patient-reported outcomes. This approach holds promise in reducing both direct and indirect costs associated with IBD.

The care model consists of several key components: an initial visit, ongoing multidisciplinary assessments, and periodic follow-ups to ensure treatment effectiveness. The initial component of the model involves a one-time “initial visit”, which assesses the patient’s clinical status upon referral to a specialized centre. During this initial visit, a detailed history and physical examination are conducted, care outcomes are reviewed, and the effectiveness and safety of current medications are evaluated.

A “complex visit” may also be offered, typically involving a multidisciplinary team of three to four specialists, such as a gastroenterologist, surgeon, and nurse, as well as a dietitian and psychologist, who collectively review the patient’s status and refine the IPOC while evaluating disease-modifying treatments and additional diagnostic procedures.

Once every 12 months, an annual review visit should be conducted for all patients in reference centres to reassess treatment response, disease activity, pain levels, and comorbidities. A comprehensive reassessment of laboratory and imaging results is essential to ensure consistency in the management strategy for each patient. In addition to these consultations, at least two educational visits per year with a gastroenterology nurse and at least two sessions with a dietitian to optimise nutritional care should be scheduled.

Finally, same-day admissions to gastroenterology wards should be available for managing complications, such as anaemia and for performing additional interventions, including vaccinations and medication level measurements, during a single visit.

Quality measurements

In Poland, the Crohn’s Disease Registry, initiated in 2005, represents a collaborative effort by leading IBD care centres and serves as an epidemiological survey. This registry has provided the first reliable demographic and clinical data on Polish IBD patients at this scale. However, this registry primarily serves as an epidemiological database and does not comprehensively track therapy or long-term outcomes, or quality of care indicators. Furthermore, it was not fully integrated with national eHealth systems, limiting its potential for real-time data analysis and automated reporting. To improve the monitoring of care quality in chronic diseases, the establishment of a comprehensive registry is recommended. This registry would integrate with existing healthcare information systems and could progressively automate data collection in the era of digital transformation.

Currently, there are 13 health condition registries under the Ministry of Health that could be expanded to include IBD care monitoring. These registries could either stand alone for specific data collection or be integrated within the eHealth Centre (CEZ), as has been done in the National Oncology Network (KSO) with the eDiLO (e-Card for Oncology Diagnosis and Treatment).

The structured digital care pathways can be harmonised to measure (semi-) automatically key outcome quality indicators and enable comparisons between institutions. Indicators of health outcomes can be divided into three main groups (Table I) [19, 20]. The first group relates to the adequate prevention of disease complications and undesired drug effects, vaccination rates, and tests for the early identification of CD relapse after surgical treatment. The second group concerns the monitoring of the adequacy of treatment, for example, assessing indications for biologic therapy in steroid-resistant UC. Finally, the third group encompasses a substantial number of indicators emphasising the importance of strengthening patient autonomy by providing comprehensive information, enabling informed decision-making, and encouraging active patient involvement in their own care (more in Table I).

Table I

Conclusions

The aim of this model is to ensure that the patient has access to comprehensive and coordinated care, including multidisciplinary collaboration, appropriate monitoring and timely access to care in the event of exacerbations or when the surgery is required. Comprehensive coordinated care should be based on reference centres providing outpatient treatment, drug treatment programmes, and surgical interventions. The expected outcome of comprehensive care is to improve patient health by: implementing appropriate-quality care (especially outpatient care) for patients with IBD according to stage, ensuring effective treatment, including disease activity assessment, and reducing relapse rates, including hospitalisations and surgical procedures. As shown by previous experience with the implementation of similar solutions in Poland (KoS-Myocardial Infarction [21], coordinated primary care), the implementation of comprehensive and integrated care, with data collection and changes in the principles of financing and the scope of services, may lead to measurable benefits in public health.