Colonic varices are extremely rare and associated with portal hypertension due to liver cirrhosis, portal vein thrombosis, or hepatic vein thrombosis. Myeloproliferative disorders, protein C or S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency, and factor V Leiden are other common causes. The presence of diffuse colonic varices without any known etiology is called idiopathic colonic varices (ICV) [1]. Colonic varices are usually detected on physical examination or during acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding or chronically with iron deficiency anemia [2]. ICV can usually be conservatively treated. However, segmental or total colon resection may be necessary in cases with uncontrolled massive bleeding [3]. The author reports a patient presenting for gastrointestinal bleeding, diagnosed with idiopathic colonic varices.

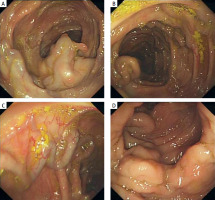

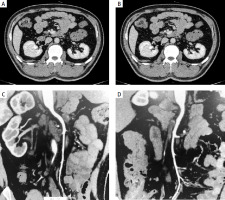

A 45-year-old male patient was referred to our hospital with a 1-day history of melena, dizziness, palpitations, weakness, and transient loss of consciousness. On examination, he appeared pale. Laboratory tests were all within the normal range except for iron deficiency anemia (Table I). Chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT) were unremarkable. Gastroscopy revealed no bleeding site. An ultrasound scan of the abdomen showed normal appearance of the liver, spleen, and pancreas. No signs of thrombosis of the portal axis were detected in Doppler examination. Colonoscopy revealed exaggerated vasculature of the colon (varices) (Figure 1). Mesenteric CTA indicated tortuous and increased varicose veins in the transverse colon, ascending colon and small intestine (Figure 2). The case was discussed, and a decision was made to proceed with internal medicine conservative treatment with fasting, nutritional support, and fluid therapy. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged. The patient had hemorrhage of the digestive tract again 1 year later. The evidence again demonstrated total colonic varices, and the patient was advised surgery but declined the procedure.

Table I

Laboratory data on admission

[i] WBC – white blood cells, RBC – red blood cells, HGB – hemoglobin, PLT – platelets, HCT – hematocrit, TP – total protein, ALB – albumin, TBIL – total bilirubin, DBIL – direct bilirubin, IBIL – indirect bilirubin, AST – aspartate aminotransferase, ALT – alanine aminotransferase, ALP – alkaline phosphatase, GGT – gamma-glutamyltransferase, BUN – blood urea nitrogen, UA – uric acid, CR – creatinine, TG – triglyceride, CHOL – total cholesterol, LDH – lactate dehydrogenase, UIBC – unsaturated iron binding capacity, ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate, HBs-Ag – hepatitis B surface antigen, HBs-Ab – hepatitis B surface antibody, HBe-Ag – hepatitis B e antigen, HBe-Ab – hepatitis B e antibody, HBc-Ab – hepatitis B core antibody, HCV-Ab – hepatitis C virus antibody, PT – prothrombin time, APTT – active partial thromboplastin time, FIB – fibrinogen.

Colonic varices are a rare condition. In most cases, it is caused by portal hypertension, with a prevalence of 1–8% when it is associated with a portal condition. However, when it is not associated with concomitant diseases, it is called idiopathic, with a prevalence rate of around 0.07% [4, 5]. Idiopathic colonic varices are seen more often in males at a younger age, with the median age of diagnosis being 41 years [6].

The diagnosis and etiology of idiopathic colonic varices are difficult to determine, and require laboratory and imaging tests to rule out secondary causes. Relevant tests to be completed include: blood routine, liver function, hepatitis serology, liver ultrasound, portal vein ultrasound, portal venography, and liver elastography. CT angiography or mesenteric angiography is the most accurate diagnostic tool [7]. Angiography shows dilated vessels and prolongation of the venous phase. Colonoscopy is a diagnostic option. During the endoscopy, colonic varices are identified by dilated, tortuous vascular tracts with a bluish tinge on the mucosal surface. Our patient was diagnosed appropriately with colonic varices through CT angiography and colonoscopy.

Due to the rarity of colonic varices, there are currently no adequate treatment guidelines. The treatment options of idiopathic colonic varices vary from conservative management to surgical excision depending on the bleeding status. An operation of the affected segment of bowel seems to be the safest method, but it is highly invasive [8, 9]. The short-term prognosis appears favorable with endoscopic hemostasis therapy, including mechanical, thermal, and injection therapy or a combination thereof, but the long-term prognosis is unclear [10]. Most cases with hematochezia show no active bleeding during colonoscopy; therefore, conservative treatment may be preferred. In our case, we applied conservative treatment, with satisfactory results.

In conclusion, ICV is a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding, a disease that requires the exclusion of portal hypertension and portal vein thrombosis-like disorders, which have a familial tendency but are not the full cause. Some patients are diagnosed incidentally during colonoscopy, and selective angiography is the gold standard for the imaging diagnosis of this disease when bleeding from colonic varices is present. Conservative treatment is generally prefered as the first line of treatment, and when conservative treatment is not effective, surgical procedures and vascular interventions may be considered.