Introduction

Chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) is one of the most frequent complaints in primary care [1]. After excluding secondary causes of constipation, arising from mechanical obstacles, neurodegenerative and neurologic disorders, neuroendocrine diseases, electrolyte disturbances, and drug-related adverse events [2], CIC disorders can be classified as: i) functional defecation disorder (FDD), further sub-classified as inadequate defecatory propulsion or dyssynergic defecation; ii) slow-transit constipation (STC), and iii) normal transit constipation, further subclassified as functional constipation (FC) and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C). These classifications are not mutually exclusive, and significant overlap exists [3]. It has been estimated that CIC was the leading problem identified in a patient visit from more than three billion patient visits yearly in medical centres in the United States [4, 5]. The annual cost of treatment of CIC ranges from $1912 to $7522 per patient, while treatment of a patient with IBS-C costs around $1356 [6]. Almost half of patients with symptoms of CIC are not satisfied after medical advice and therapy, mostly due to lack of therapeutic efficacy and uncertainty concerning its safety [7].

The pathophysiology of CIC is complex and not well understood. The following mechanisms have been implicated in its pathogenesis: i) gastrointestinal motor dysfunction, ii) slow colonic transit in STC, iii) inadequate peristaltic movements, iv) failure in smooth muscle relaxation, v) overactivity of the colonic wall, and vi) microbiota and gut-brain axis (GBA) alterations [2].

Patients with normal colonic transit constipation represent the most prevalent subgroup of CIC with unclear pathophysiology. Patients with FDD represent the second most common group of CIC disorders, with paradoxical anal contraction, failure or impairment of anal relaxation, or inadequate rectal and abdominal propulsive forces implicated in pathogenesis [8]. Patients with STC are the least prevalent CIC subgroup with limited or absent increase in postprandial motor activity and impaired retrograde colonic propulsion [8].

The high prevalence of CIC and low or moderate treatment efficacies warrant the development of new forms of therapy. Among various therapeutic methods in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), probiotics are gaining popularity and have become widely used in clinical practice [9, 10]. To show a clinical relationship between a studied probiotic at a certain dose, clinicians have to evaluate its effect size and duration of action. Determination of replicability and reproducibility of each finding, the biological likelihood, and potential explanation of proposed interactions and alternatives are of particular interest [11]. Finally, it is necessary to evaluate how the discovered relationship conforms with current knowledge.

Because differences in interpretations of epidemiological findings can exist between various experts and authorities, well-powered, appropriately-designed studies, preferably with a high level of evidence (i.e. systematic reviews and meta-analyses), are essential to draw conclusions regarding causation and to develop guidelines and recommendations.

Unfortunately, it should be noted that high-quality data from nutrition-related interventions rarely exist. In parallel, as stated by the expert panel of the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), bacteria-containing food and supplements should be evaluated as food and dietary supplements overall [12]. Because no probiotic claims for probiotics in foods in the European Union (EU) have been judged to be sufficiently substantiated, medical authorities now recommend microbial supplements on the basis of scientific literature and recommendations published by health-related practitioners.

In the last decade only a few meta-analyses and recommendations evaluating utility of probiotics in CIC have been published. Several conclusions conflicted, making judgment difficult. There was also great uncertainty among medical professionals as to the choice of an adequate interventional protocol. The aim of the present review is to update readers concerning possible mechanisms of the action of probiotics in CIC and to analyse published systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and recommendations regarding their effectiveness in adults with CIC.

CIC diagnosis: The Rome IV criteria for functional constipation, constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, and functional defecation disorders

FGIDs and bowel disorders (BDs), according to the Rome IV diagnostic criteria, result from improper gut-brain interactions. FGIDs and BDs are currently defined as a group of disorders classified by gastrointestinal symptoms related to any combination of: i) motility disturbances, ii) visceral hypersensitivity, iii) altered mucosal and immune function, iv) gut microbiome, and/or v) central nervous system processing [13]. The Rome IV criteria introduced a modern definition of functional manifestation of the disease on the basis of its pathophysiology rather that its non-organic cause [14].

Functional constipation (FC) is a functional bowel disorder of difficult, infrequent, or incomplete defecation [15]. In 2007, using the Rome II criteria, Choung et al. identified that a 12-year cumulative incidence of constipation was as high as 17% [16]. Female gender, reduced caloric intake, and age over 50 years were recognised as pivotal risk factors of this condition [17, 18]. However, the terminology and definitions of FC are not always appropriate. In this regard it is noteworthy that Rome IV criteria do not use the term “chronic idiopathic constipation”. However, this term does appear in many studies [19] and can be viewed as an umbrella term for all functional defecation disorders. Brandt et al. defined CIC as the presence of unsatisfactory defecation for at least 3 months and characterised by infrequent stools, difficult stool passage, or both [20]. This definition does not correspond to a category in the FC Rome IV criteria, but patients diagnosed with CIC are frequently considered as patients with FC [21]. Because the use of multiple definitions of CIC may lead to conceptual confusion, researchers are strongly encouraged to use Rome IV criteria for definitions and terminology for clinical trials and clinical assessment of participants suffering from chronic constipation.

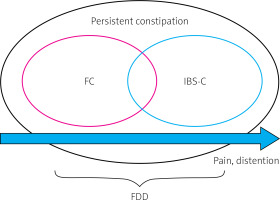

Constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) is a subtype of IBS in which pain, distension, bloating, and constipation [15] are predominant symptoms of the disease (Table I). The global prevalence of IBS was estimated to be around 11%, with almost 30% as cases of IBS-C. The incidence was higher in women and individuals below 50 years of age [22–24]. Clinical differentiation between FC and IBS-C may introduce many difficulties as the diagnoses overlap [25–28]. Thus, FC and IBS-C should be considered as part of a continuous spectrum of disorders rather than isolated diseases [15, 29] (Figure 1, Table I). Patients with FDD may fulfil the Rome IV symptom criteria for either FC or IBS-C. The criteria for FDD also require the presence of at least two out of three independent clinically-validated physiological tests: i) abnormal balloon expulsion, ii) an imaging study documenting improper evacuation, and iii) anal manometry or surface electromyographic activity (EMG) documenting abnormal anorectal evacuation [30].

Table I

Diagnostic criteria for functional constipation (FC) and constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) [15]

CIC pathophysiology

Pathophysiology of constipation in functional bowel disorders has a multifactorial origin. As a family history of chronic constipation has been reported, CIC is thought to have a genetic background [31, 32], but data concerning this are scarce. Genes suggested to be involved in constipation include a membrane-bound bile acid receptor, TGR5 (also known as GpBAR1) [33], as well as the α-subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.5, namely SCN5A [34]. Limited data show that the average rate of penetration of genetic changes in the global population is difficult to assess.

It has been confirmed that in STC individuals abnormal motility may result from skewed serotonin signalling [25], a decreased level of P substance in enteric nervous system in mucosa and submucosa [35], low neural density in myenteric plexus, excessive count of nitric oxide-positive neurons and low count of vasoactive intestinal peptide-positive neurons [36], changes within colonic endocrine cell composition [37], and/or diminished volume of colon interstitial cells [38, 39]. These may all result in altered gastrointestinal (GI) motility, visceral hyperalgesia, immune activation, and increased intestinal permeability. Altered intestinal microbiome composition allows improper communication within the GBA and thus may be involved in the aetiology of the condition [14]. In fact, diverse gut microbiota are essential for many physiological processes, including immune response and GI function [40]. Neuroactive molecules produced within the gut ecosystem, via auto, para-, or endocrine mechanisms, influence mucosal secretion, smooth muscle motility, and intestinal blood flow. Transmission of neural signals via vagal afferent nerves and interneurons close the gut-brain communication circle [41].

Gut microbiome alteration in constipation

The human intestine forms a habitat for more than 1000 different species of microorganisms, predominantly bacteria, hence the number of microbiotic cells is nearly equal to the number of host’s cells [42, 43]. There is an increasing body of evidence that alteration of gut microbiota may contribute to the development of functional bowel disorders, which may be secondary to gut microbiota dysbiosis responsible for altered metabolic activity [15]. The putative microbiotic-dependent mechanisms in chronic constipation are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Putative microbiotic-dependent mechanisms in chronic constipation

BA – bile acids, ENS – enteric nervous system, SCFAs – short-chain fatty acids.

In experimental and clinical studies, changes in microbiota associated with the occurrence of FC have been observed [44]. A direct relationship between microbiota and constipation was demonstrated in an experiment conducted by Ge et al. [19]. In this rodent study a 4-week, broad-spectrum, antibiotic therapy was followed by faecal microbiome transplantation (FMT) from constipated or healthy donors [19]. Mice receiving transplants from constipated donors were more likely to develop constipation in comparison to the control group. The authors evaluated microbiotic metabolites and found that short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and secondary bile acids (sBAs) were decreased in mice transplanted [45] with faeces collected from constipated humans.

However, the results of experimental investigations have not been confirmed by direct observations in human studies. Recently, an elegant paper authored by Ohkusa et al. summarised gut microbiotic fingerprints in constipated patients [44]. The report covered patients diagnosed with both FC and IBS-C. Different methods of microbiotic analyses were utilised in recruited patient cohorts. Historically these were culture dependent, whereas more recently sequence-based genetic and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) techniques have been used, together making it extremely difficult to pool results and draw conclusions. For instance, Khalif et al. found that patients diagnosed with FC had lower abundance of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Clostridium, and Bacteroides and elevated counts of Enterobacteriaceae (namely E. coli) and S. aureus along with fungi [46]. However, these results were based on microbial culture analysis of faecal samples. Similarly, Kim et al. found that patients diagnosed with FC had significantly diminished counts of Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides compared to healthy controls [47]. In patients suffering from IBS-C the most prevalent cases had lower faecal abundance of Actinobacteria, including Bifidobacteria, along with higher counts of Bacteroidetes in gut mucosa. All in all, there are no consistent findings concerning typical gut microbiotic alterations for constipated patients. Currently, faecal microbiotic alterations cannot be used as a marker for constipation or as a treatment marker. More studies, characterising not only skewed bacterial abundance but also with dysbiotic metrics such as α- and β-diversity and consequent descriptions of disrupted metabolic functioning of the microbiome, are necessary, especially in constipated patients stratified according to clinical indices such as effectiveness of treatment [48]. New hope should also be directed towards new methods of microbiome analysis including measurement of its function, i.e. whole genome sequencing and use of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Gene Systems (KEGG), ortholog prediction [49] using the Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) [50], as well as the assessment of metabolic activity of microbiota (e.g. production of short-chain fatty acids) [51].

Possible involvement of microbiota in chronic constipation

Gut microbiota affect the structure and function of the central nervous system due to interactions with enterochromaffin cells and vagal afferent nerve pathways [52, 53]. Rome IV criteria emphasise that the gut-brain axis may be involved in the aetiology of functional bowel disorders [15]. These pathways might serve as potential targets for future interventions.

Intestinal bacteria affect gut motility and are involved in enteric nervous system (ENS) development, SCFA synthesis, and bile acid metabolism [54, 55]. Bacterial colonisation of germ-free mice provide key factors for understanding the development of the ENS [56]. Agitation within the ENS is transmitted via fast-acting catecholamines and slow-acting neuropeptides. Additionally, the inflammatory response – as a consequence of disruption within the gut microbiome and thus the intestinal barrier – is influenced by sensory neurons. This neural activity may originate from neurogenic inflammation (by means of vasodilatation and plasma extravasation) and independently increase the synthesis of neuropeptides [57, 58]. Norepinephrine increases the pathogenic properties of bacteria and viruses rendering them susceptible to dendritic cells, which consequently increases the intensity of inflammation [59]. To close the circle, different gut microbiotic metabolites regulate the function of the myenteric plexus, thus affecting visceral perception, motility, as well as secretory and motor functions of the GI tract [60–63]. For example, SCFAs stimulate colonic blood flow and gut motility [64]. Products of metabolism from colonic anaerobic bacteria, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, stimulate ileal propulsive contractions as a result of serotonin secretion [65]. Furthermore, bacterial bile acid metabolites, i.e. deconjugated bile salts, may stimulate colonic motor response [66]. SCFA and BA levels are altered in patients with FC and/or IBS-C. Currently, there is evidence that the SCFA level is typically increased [67], and BA decreased [68], among constipated patients. Lastly, environmental stimuli, including psychological stress, have been recognised as gut-barrier integrity disruptors [69].

Another possible link between constipation and microbiota may be small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) [70]. SIBO was shown to be associated with prolonged small bowel transit time [71]. Sarosiek et al. observed that in patients with chronic constipation, lubiprostone increased the frequency bowel movements. Moreover, 41% of patients who were recognised as SIBO-positive became SIBO-negative after treatment [72]. In the aforementioned study, all SIBO-positive patients were tested positive for both methane and hydrogen in breath tests. Therefore, both methane and hydrogen may contribute to constipation in SIBO-positive individuals [72]. However, Grover et al. reported that methane alone, regardless of the presence of SIBO, was linked to IBS-C [73]. It is likely that SIBO enhances constipation via methane and hydrogen production. Of note, SIBO might arise secondarily to diminished intestinal clearance in patients with decreased bowel motility. All of the above may accelerate a circle of constipation-related causes, although these interactions require further investigation.

Probiotics in CIC treatment

Because FGIDs are associated with improper signalling within the GBA, the microbiome may provide a guide towards therapies to counteract or relieve constipation. Probiotics contain live microorganisms, which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit to the host [74]. Probiotics have been used successfully in patients with various FGIDs, and some recommendations concerning use of probiotics in clinical practice are already available [9, 75]. However, their use in constipated individuals is still controversial. The effects of probiotics are modest and depend on the strain and the available meta-analyses cover data from interventions with both single-strain or multi-strain probiotic formulations.

In addition, probiotic dose and timing of administration vary among reported clinical trials. In particular, the number of bacteria colony-forming units (CFU) in the probiotic formulations were neither assessed nor confirmed in most clinical interventions conducted. Medical practitioners often recommend probiotics by rebound to patients demands and/or on the basis of available internet recommendations.

To assess the efficacy of probiotics in constipation, we analysed the results of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in this field. We also compared the results of meta-analyses with available guidelines and recommendations published so far.

Systematic review of literature

We conducted PubMed and Google Scholar searches using the following search strings: 1. (constipation OR IBS OR IBS-C OR functional) AND probiotics AND (recommendations OR guideline OR meta-analysis OR systematic review) and 2. title: probiotic AND guidelines, to evaluate the opinion of health-related authorities toward probiotics in constipated patients. The electronic search was supplemented by a manual review of the reference lists from eligible publications and relevant reviews. The search was carried out from the databases’ creation until 15.04.2019.

Our inclusion criteria were as follows

documents (recommendations/guidelines/meta-analyses/systematic reviews), in which the effectiveness of probiotics in patients with constipation/FGIDs/healthy persons with infrequent bowel movements was analysed;

documents (recommendations/guidelines/meta-analyses/systematic reviews) in humans;

documents in English/Polish.

Exclusion criteria were:

Results of systematic search

The initial number of publications found (hits) were 536. After the title and abstract review and removal of duplicates, we included 33 papers for the full-text analysis phase. Finally, we extracted data from 18 publications (for details see flowchart in Figure 3). The results from guidelines and recommendations (n = 10) on probiotic utility in constipation are presented in Tables II and III. In parallel we compared the results of meta-analyses/systematic reviews (n = 8) that evaluated the efficacy of probiotics in constipation.

Table II

Summary of probiotic recommendations in constipation

| Summary of statement | Recommendation level | Quality of evidence^ | Recommended strain/dose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment for constipation in IBS is recommended in some patients. Different decisions are appropriate for different patients, depending on the patient’s situation but also on personal opinions and preferences. The majority of patients (> 50%) would decide in favour of the intervention, but many would not. Therapeutic approaches to try for constipation include probiotics | Recommendation strength – weak for: different decisions are appropriate for different patients, depending on the patient’s situation but also on personal opinions and preferences. The majority of patients (> 50%) would decide in favour of the intervention, but many would not. Strong consensus | Evidence level A (highest, from A-D scale) | Nd/nd | [83] |

| Specific probiotics may help reduce constipation in some patients with IBS | Level of agreement: 60% | Low | B. animalis subsp. lactis DN-173 010, B. animalis subsp. lactis HN019/nd | [81] |

| Specific probiotics help improve frequency and/or consistency of bowel movements in some patients with IBS | Level of agreement: 70% | Moderate | B. animalis subsp. lactis Bb12, B. animalis subsp. lactis DN-173 010, B. animalis subsp. lactis HN019, B. bifidum MIMBb75, B. longum subsp. infantis 5624, Escherichia coli DSM17252; investigative combinations (1 – Bifido-bacterium longum subsp. longum 46 and B. longum subsp. longum 2C; 2 – Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bb12 and Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei CRL-431, 3 – Lactobacillus acidophilus-SDC 2012 and L. acidophilus-SDC 2013, 4 – Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, L. rhamnosus Lc705, Propionibacterium freudenreichii subsp. shermanii JS and Bifidobacterium breve Bb99); marketed combinations (1 – Lactobacillus acidophilus LH5, L. plantarum LP1, L. rhamnosus LR3, Bifidobacterium breve BR2, B. animalis subsp. lactis BL2, B. longum subsp. longum BG3 and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus ST3, 2 – Lactobacillus acidophilus (CUL60 and CUL21), Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis CUL34 and B. bifidum CUL20, 3 – Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum LA 101, Lactobacillus acidophilus LA 102, L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis LA 103 and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus LA 104)/acc. to manufacturer’s recommendations at least for a month | |

| There is insufficient evidence to recommend probiotics in CIC (methodological weakness of the studies and high or unclear risk of bias) | Weak | Very low | Nd/nd | [21] |

| Probiotics are not recommended in patients with IBS-C and FC (conflicting results regarding effectiveness) | Nd | Nd | Nd/nd | [84] |

| The administration of specific probiotics in patients with chronic constipation accelerates bowel transit and increases the frequency of bowel movements. We suggest the use of probiotics in the treatment of chronic constipation in the adult population | Level of agreement: 100% | High to moderate | B. lactis HN019, B. lactis DN-173 010, L. casei Shirota, and E. coli Nissle 1917/nd | [76] |

| Specific probiotics may help reduce constipation in some patients with IBS | Level of agreement: 87.5% | Low | Nd/nd | [82] |

| Specific probiotics help improve frequency and/or consistency of bowel movements in some patients with IBS | Level of agreement: 100% | Low | Nd/nd |

^ according to http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org

IBS – irritable bowel syndrome. For further abbreviations see Fig 1.

Table III

Summary of probiotic guidelines in constipation

| Strain | Dose | Level of evidence* | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium bifidum (KCTC 12199BP), B. lactis (KCTC 11904BP), B. longum (KCTC 12200BP), Lactobacillus acidophilus (KCTC 11906BP), L. rhamnosus (KCTC 12202BP), and Streptococcus thermophilus (KCTC 11870BP) | 2.5 × 108 CFU/ day | III* | [80] |

| Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 | 1 × 108 CFU/twice daily | III* | |

| L. reuteri DSM 17938 | 108/tab; 1 tab/day | I* | [77] |

| Combination of the following strains: L. acidophilus SD5212, L. casei SD5218, L. bulgaricus SD5210, L. plantarum SD5209, B. longum SD5219, B. infantis SD5220, B. breve SD5206, S. thermophilus SD5207 | 45 × 1010/sachet; 1–4 sachets/day | II* | |

| L. reuteri DSM 17938 | 108/tab; 1 tab/day | I | [78] |

| B. (animalis) lactis CNCMI-2494 | 109/lq; 1–3 servings/day | I | |

| Combination of the following strains: L. acidophilus SD5212, L. casei SD5218, L. bulgaricus SD5210, L. plantarum SD5209, B. longum SD5219, B. infantis SD5220, B. breve SD5206, S. thermophilus SD5207 | 45 × 1010/sachet; 1–4 sachets/day | II | |

| L. reuteri DSM 17938 | 108/tab; 1 tab/day | I | [79] |

| B. (animalis) lactis CNCMI-2494 | 109/lq; 1–3 servings/day | I | |

| L. acidophilus DSM24735, L. paracasei DSM24733, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus DSM24734, L. plantarum DSM24730, B. longum DSM24736, B. infantis DSM24737, B. breve DSM24732, S. thermophilus DSM24731 | 45 × 1010/sachet; 1–2 sachets/day or 90 × 1010/sachet; 1 sachet/day | II |

[i] I – Evidence obtained from at least one correctly designed randomised trial (Highest Level), II – nonrandomised controlled cohort/follow-up study, III – randomised trial or observational study with dramatic effect, II* – Randomised trial or observational study with dramatic effect, III* – nonrandomised controlled cohort/follow-up study.

We obtained data on the number of participants, duration of probiotic intervention, doses of probiotics, and the names of the strains that were used. Additionally, we noted the main results and conclusions and most importantly the trial quality indices (risks of bias). Only data on constipation-related study characteristics and outcomes were abstracted. In case of more than two study arms, data were abstracted separately for probiotic doses. The details are given in Table IV. Among 10 papers comprising guidelines and recommendations, six evaluated probiotic efficacy in patients diagnosed with chronic/functional constipation [21, 76–80] and four concerned constipation-related outcomes in patients with IBS-C [15, 81–83].

Table IV

Summary of probiotic systematic reviews and meta-analyses of constipation studies

| Type of study/disease/number of trials | Duration of study [days]/number of participants | Doses (range, CFU) | Main results | ROB | Conclusions | Strain/recommended dose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic review of randomised controlled trials/Constipation/n = 3 | 14–28/266 | 6.5 × 109– 1.25 × 1010 | There is very limited evidence available from controlled trials to evaluate with certainty the effect of probiotic administration on constipation. Some strains can have favourable effects in adults with constipation (increase defecation frequency and improve stool consistency) | Publication bias led to exclusion | Lack of sufficient scientific evidence to support a general recommendation about the use of probiotics in the treatment of functional constipation. Probiotics as an integral part of treatment in constipation should be considered investigational | Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173010, Lactobacillus casei Shirota and Escherichia coli Nissle 1917/nd | [85] |

| Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials/IBS-C and constipation/healthy/n = 11 (n = 13 treatment effects); healthy n = 6 | 11–28/464 | 0.49 × 109– 97.5 × 109 | Probiotic decreased intestinal transit time (ITT) (SMD = 0.40; 95% CI: 0.20–0.59, p < 0.001). Constipation (r 2 = 39%, p = 0.01), higher mean age (r 2 = 27%, p = 0.03), and higher percentage of female subjects (r 2 = 23%, p < 0.05) were predictive of decreased ITT. Greater reductions in ITT with probiotics in subjects with vs. without constipation and in older vs. younger subjects [both SMD: 0.59 (95% CI: 0.39–0.79) vs. 0.17 (95% CI: –0.08–0.42), p = 0.01. Medium to large treatment effects were identified with Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 (SMD: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.27–1.18, p < 0.01) and B. lactis DN-173 010 (SMD: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.15–0.94, p < 0.01) while other single strains and combination products yielded small treatment effects | Overall medium quality as evaluated by Jadad score (median: 3); Unclear method of randomization (11/14), subject accountability in RCTs (7/13) | Short-term probiotic supplementation decreases ITT: the effect size was greater in constipated or older adults and with certain probiotic strains | B. lactis HN019, B. lactis DN-173 010/1.8 × 109–17.2 × 109 CFU 18.75 × 109–97.5 × 109 CFU | [91] |

| Meta-analysis/IBS/n = 10 (stool frequency n = 5, stool consistency n = 2) | 27–122/stool frequency n = 227; stool consistency n = 73) | 8–9 × 109– 45 × 1010 | Probiotics containing B. breve, B. infantis, B. longum, L. acidophilus,L. bulgaricus, L. casei, L. plantarum, or S. salivarius spp. thermophilus species did not improve frequency scores according to the meta-analysis. Probiotics containing B. breve, B. infantis, B. longum, L. acidophilus, L. bulgaricus, L. casei, L. plantarum, or S. salivarius spp. thermophilus species did not significantly improve consistency scores according to the meta-analysis | Medium-to-high quality as evaluated by Jadad score (median: 4) | The effects of probiotics on the frequency or consistency of stools should be studied with caution because these factors vary in IBS patients. Further analyses should be performed on the stool profiles of these patients | Nd/nd | [92] |

| Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials/functional chronic constipation/ n = 14 | 14–56/1182 | 108 – 3 × 1010 | Significantly reduction of whole gut transit time by 12.4 h (95% CI: –22.3, –2.5 h) and increasing stool frequency by 1.3 bowel movements/wk (95% CI: 0.7, 1.9 bowel movements/wk), and this was significant for Bifidobacterium lactis (WMD: 1.5 bowel movements/wk; 95% CI: 0.7, 2.3 bowel movements/wk) but not for Lactobacillus casei Shirota (WMD: –0.2 bowel movements/wk; 95% CI: –0.8, 0.9 bowel movements/wk). Probiotics improved stool consistency (SMD: +0.55; 95% CI: 0.27–0.82), and this was significant for B. lactis (SMD: +0.46; 95% CI: 0.08–0.85) but not for L. casei Shirota (SMD: +0.26; 95% CI: –0.30, 0.82). No serious adverse events were reported | High risks of bias: attrition (4/14), selective reporting (11/14); Unclear risk of bias: selection bias (10/14) | Whole gut transit time, stool frequency, and stool consistency may be improved with probiotics. More powered RCTs are required to assess optimal strains, doses, and duration of probiotic therapy | Bifidobacterium lactis strains: BI-07, DN 173 010, GCL2505, HN019, LMG, P-21384/ > 1 × 107 CFU/g – 1.25 × 1010 CFU/d | [86] |

| Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials/CIC/n = 3 | 14–28/245 | 1.2 × 109–6.5 × 109 | Dichotomous outcomes: beneficial effect of probiotics, in terms of failure to respond to therapy, when data were pooled the overall result was not statistically significant (RR of failure to respond to therapy = 0.29; 95% CI: 0.07–1.12), with significant heterogeneity between the two trials (I 2 = 71%, p = 0.06). In two RCTs probiotics increased mean number of stools per week = 1.49; 95% CI: 1.02–1.96) | High risk of bias: randomization and concealment; Unclear risk of bias: no indication on whether other CIC drugs used | The efficacy of probiotics in CIC is uncertain | L. casei Shirota, L. casei YIT 9029 FERM BP-1366/6.5 × 109/day | [21] |

| Systematic review of systematic reviews and evidence-based practice guidelines/IBS/n = 10 –bowel movements (IBS-C – n = 4) | 28–84/1292 | 106–1.32 × 1010 | Probiotics did not provide clinically meaningful improvement in constipation (three RCTs only were analysed). Marginal improvements were shown for B. infantis 35624 in bowel habit satisfaction at 4 weeks and for a three-strain probiotic B. lactis DN73010, S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus. Colonic transit time improved from 56 h down to 12 h (21%; p = 0.026). The same dose-specific probiotic used in two large RCTs did not show benefit compared to placebo | High risk of bias: incomplete outcome data (2/4), selective reporting (3/4); unclear risk of bias: random sequence generation (3/4); allocation concealment (3/4), blinding of outcome assessment (1/4) | Due to result heterogeneity specific probiotic recommendations for IBS management in adults were not made | B. infantis 35624 at a dose of 1 × 108; three-strain probiotic B. lactis DN73010, S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus at a dose of 1.25 × 1010 +1.2 × 109 | [90] |

| Systematic review/Constipation/9 (n = 4 - RCT, n = 5 observational) | 46–175/778 | 109–45 × 1010 | Probiotics significantly improved constipation in elderly individuals by 10–40% compared to placebo controls | High risk of bias: none; Unclear risk of bias: allocation concealment (2/3), blinding outcome assessment (2/3), selective reporting (2/3) | Due to heterogeneity of study designs and populations and high risk of bias the results need to be taken cautiously | The most commonly tested, however not clearly indicated as best formulations, were Bifidobacterium longum SPM 1205, Bifidobacterium longum BB536 (H and L), B. longum (46 and 2C)/nd | [88] |

| Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials/constipated adults/n = 21 (23 comparisons) | 7–84/2656 | 0.1 × 109– 30 × 109 | Probiotics increased weekly stool frequency by 0.83 (95% CI: 0.53–1.14, p < 0.001), but after adjustment for publication bias, the mean difference in weekly stool frequency was reduced from 0.83 to 0.30. Probiotic-containing products reduced ITT (SMD = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.33–0.97, p < 0.001). The SMD in ITT was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.20–1.41, p < 0.01) for products containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, 0.72 (95% CI: 0.37–1.07, p < 0.001) for products containing Bifidobacterium only, and 0.27 (95% CI: -0.18 to 0.72, p = 0.24) for products containing Lactobacillus only | Medium-to-high quality as evaluated by Jadad score (median: 4); Unclear method of randomization (15/23#), Subject to accountability in RCTs (23/23#), unclear double blinding (8/23#) | Supplementation with probiotics increases stool frequency and reduces ITT in constipated adults but due to heterogeneity of studies and biased results must be considered with caution | Nd/nd | [89] |

There were two recommendation papers that did not find any reasons to use probiotics as a treatment option [21, 84], four documents in which authors concluded that probiotics may be beneficial but in only a subgroup of patients [76, 81–83], and four which provided exact probiotic strains as effective in treatment of constipation using levels of evidence based on the design of clinical trials (level I – randomised clinical trials (RCT), level III- nonrandomised studies). Among meta-analyses and systematic reviews there were five papers with studies conducted in a population of patients with constipation [85–89] and three in persons diagnosed with IBS-C [90–92]. Out of six studies evaluating probiotic therapy as an integral part of constipation treatment, the results of four were negative [85, 87, 90, 92] and two were positive [88, 91]. Intestinal transit time was examined in four publications, all of which concluded that such intervention was beneficial regarding bowel movement [86, 89–91].

Of note, we found some papers (N = 15) that covered IBS therapeutic approaches where probiotics were recommended/evaluated as a highly recommended treatment option, but the authors of the different studies examined different IBS subtypes as mixtures or did not report on improved intestinal transit time/bowel movements frequency/stool consistency [75, 87, 90, 93–104]. These documents were not placed in Tables II–IV.

Overall, there seemed to be an agreement that probiotics may improve intestinal motility, but medical authorities predominantly recommended probiotics as an integral part of treatment for constipation cautiously. The majority did not state an exact probiotic strain, optimal dose, or duration of such intervention. There was large heterogeneity among the study designs, populations, and biases present in results and therefore limited overall standard of evidence. More well-powered and high-quality trials are necessary to establish a clear consensus, with exact strains, regarding the utility of probiotic supplements in patients with constipation. It must be emphasised that a few studies did not analyse multiple variables (and therefore corrections for multiple comparisons were/are necessary) for constipation-related outcomes in IBS-C patients.

Knowledge gaps

Although the effects of probiotic therapy in constipation seem promising, there are several significant gaps in clinical knowledge:

Despite the aforementioned studies, strong evidence indicating a direct interaction between probiotic strains and constipation is lacking [105]. The large heterogeneity of the studies included in the systematic reviews, as well as in meta-analyses (e.g. numbers of samples, ethnicity, methodology), makes it difficult to establish a consensus or guidelines.

All studies evaluating intestinal microbiotic composition in constipated patients and alterations following probiotic therapy were based on faecal sample analyses. As reported by Parthasarathy et al., bacteria associated with the colonic mucosal are more predictive of constipation than the luminal populations used in most of the studies [106]. This suggests that colonic biopsy may provide more accurate material for microbiome assessment and may reveal definitive bacterial taxa related to constipation.

There is a lack of large population-based RCTs concerning adults. Current results are encouraging but limited due to the low quality of the studies.

Conclusions

Although probiotics are often recommended by medical authorities, their well-established utility in adults with constipation is uncertain. Recommendations are usually based on the results of individual studies, rather than results from meta-analyses. Additionally, meta-analyses often indicate a group of probiotics rather than individual strains, which has created difficulties for physicians making therapeutic decisions. More randomised clinical studies with FC patients, utilising well-identified strains or their combinations, are necessary to deliver a high-level of credible opinion for such intervention.