Introduction

Functional dyspepsia is defined by the Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI) as any combination of postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning occurring at least 3 days per week over the last 3 months, with an onset of at least 6 months prior to evaluation. In the absence of alarm symptoms and signs, treatment can be initiated empirically without endoscopic evaluation [1]. Functional dyspepsia is further subdivided into postprandial distress syndrome and epigastric pain syndrome, depending on whether the symptoms are associated with meal ingestion [2].

The gastric symptoms of functional dyspepsia are mainly caused by impaired gastric motility and gastric hypersensitivity. These symptoms result from alteration in the brain-gut axis during the process of gastric accommodation to a meal [3]. Sympathovagal imbalance may be associated with increased hypersensitivity to visceral pain. Disruption at any level of the neural system can affect motility, secretion, immune function, perception, and emotional response to visceral stimuli in the gastrointestinal tract [4]. Evidence indicates that functional dyspepsia (FD) may be associated with symptoms observed following COVID-19 infection, highlighting it as a growing problem [5]. There are many proposed mechanisms for the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Alterations in gastric function, as measured by gastric emptying (GE) and gastric accommodation (GA), are correlated with symptoms and represent potential targets for treatment [6].

Electrogastrography (EGG) is a noninvasive technique used to record gastric myoelectrical activity (GMA) from the abdominal surface, which helps establish a cause and effect relationship between gastric motility abnormalities and dyspeptic symptoms [7]. GMA consists of spontaneous rhythmic electrical activity that determines the timing and frequency of contractile activity, including gastric emptying [8]. EGG has some limitations in accurately representing stomach contractions, their shape, pattern, and frequency. Recording with skin electrodes is subject to numerous movement artifacts and electrical interferences from other organs. Comparative studies have shown that parameters obtained from cutaneous EGG recordings are consistent with those from internal (serosal and mucosal) EGG recordings [9]. A study on canines demonstrated that while each gastric slow wave is accompanied by a contraction, this association disappears in the presence of dysrhythmia. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that a relative increase in EGG dominant power (PDP) is associated with increased gastric contractile activity [10]. Changes in the EGG PDP likely reflect alterations in gastric contractility [11].

The brain-gut axis plays an important role in regulation of gastrointestinal function, with autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity being of significant importance [12, 13]. Larger gastric distention is associated with a relative parasympathetic predominance, but this effect has not been fully elucidated [12]. Noninvasive methods for assessing autonomic system activity, such as heart rate variability (HRV), reveal the influence of sympathetic and/or parasympathetic activity on gastrointestinal effectors [14, 15].

To date, few studies have focused on assessing changes in gastric regulation in response to a meal in the presence of normal and/or impaired autonomic activity in dyspepsia [13, 16]. Food intake causes stomach distention, which triggers an ANS response [12]. Moreover, it evokes a cardiovascular response, characterized by increased sympathetic drive and decreased blood pressure (BP) due to reduced peripheral vascular resistance [12, 13].

Aim

The aim of our study was to evaluate the effect of a meal on the activity of the ANS measured by HRV and gastric myoelectric function assessed by EGG in patients with FD.

Material and methods

Study subjects

The study included 76 participants assigned to two research groups:

Dyspepsia group (FD) – included 38 patients with functional dyspepsia (12 males, 26 females, mean age: 37.8 ±11.2 years). The mean duration of dyspepsia was 3 ±1.5 years.

Patients were diagnosed according to the Rome IV Diagnostic Criteria for DGBI and were recruited based on examination by gastroenterologists from the Gastroenterology and Hepatology Department Medical College, Jagiellonian University in Cracow.

Control group (CG) – included 38 healthy volunteers (12 males, 26 females, 39.8 ±11.1 years) matched for age and sex with the dyspepsia group, without a history of gastrointestinal disorders.

Healthy controls were recruited from the University Hospital’s staff by advertisements (internet and bulletin boards). Each volunteer completed a health questionnaire and was examined by a physician.

The clinical and demographic characteristics of the enrolled participants based on their detailed medical history are presented in Table I.

Table I

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with dyspepsia and controls

Exclusion criteria were defined as: gastrointestinal disorders other than functional dyspepsia (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease), history of gastrointestinal surgery, presence of cardiovascular diseases (e.g., hypertension, coronary artery disease, and valvular heart disease), diabetes mellitus, obesity (body mass index, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), renal insufficiency, gynecological pathology, tobacco smoking, alcohol abuse, and intake of medications known to interfere with gastric myoelectric activity and autonomic nervous function.

Endoscopy was recommended for selected cases, according to guidelines and depending on age, presence of alarming symptoms, and failure of therapy, so it was not an obligatory procedure. The aim of this recommendation is to avoid unnecessary procedures [17].

According to the study protocol, all participants were asked to fast for at least 12 h prior to the study and to refrain from taking medications known to affect gastrointestinal autonomic function and motility for 3 days prior to the study.

Assessment of gastric electrical activity

Gastric myoelectrical activity (GMA) was measured with surface EGG. Thirty-minute GMA recordings in basic conditions in accordance with the research protocol were made in both groups after an overnight fast. Recordings were also taken 1 h after a standard liquid meal (oral nutritional supplement – ONS: Nutridrink, Nutricia Polska, 300 kcal/300 ml; 16% protein (9.6 g/100 ml), 49% carbohydrate (29.7 g/100 ml) and 35% fat (9.3 g/100 ml)). EGG signals were recorded using four-channel Polygraf NET electrogastrography (Medtronic, USA). Frequency ranges were defined as follows: 2–4 cpm (cycles per minute) for normogastria, 1–1.8 cpm for bradygastria, > 4–10 cpm for tachygastria and dysrhythmia time (not classified as bradygastria or tachygastria slow wave frequency). The main EGG parameters analyzed were: period dominant frequency (PDF), period dominant power (PDP) of dominant frequency (as the power or amplitude of the DF), and average percentage of slow-wave coupling (APSWC) across the multiple EGG channels. A normal range for APSWC was defined as the average percentage of time with a frequency difference of < 0.2 cpm between electrode pairs.

EGG allows reliable measurement of gastric slow wave and spike potentials that control the frequency and propagation of stomach contractions. The frequency of the gastric slow wave in healthy adult humans (normogastria) is about 3 cycles/min (cpm), with a range of 2–4 cpm, which occurs > 70% of the time. Diagnostically recognized deviations from normogastria include gastric dysrhythmias (bradygastria, tachygastria, and arrhythmia), electromechanical uncoupling (presence of normal slow waves but absence of contractile activity) and abnormal slow-wave propagation (abnormal slow wave initiation, reduced longitudinal propagation velocity, or interruption of slow wave propagation).

Assessment of autonomic nervous system activity

HRV as a beat-to-beat analysis of heart rate variability shows changes in sympathetic and parasympathetic inputs to the sinoatrial node. ANS activity was assessed by HRV analysis using Task Force Monitor 3040 equipment and Task Force Monitor V2.2. software (CNSystems, Graz, Austria). The frequency-domain signals of the RR intervals and arterial BP were analyzed using an adaptive autoregressive (AAR) model.

HRV – frequency-domain indices

The frequency-domain parameters were defined: 1) power spectral density in the range of total power (PSD, 0.0033–0.4 Hz); 2) very-low frequency (VLF, 0.0033–0.04 Hz), reflecting the influence of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system on heart rate; 3) low-frequency (LF, 0.04–0.1 Hz), which reflects the sympathetic component influenced by the oscillatory rhythm of arterial BP and depends on baroreceptor sensitivity (BRS); 4) high-frequency (HF, 0.15–0.4 Hz), which reflects the parasympathetic activity associated with breathing rate; 5) ratio of LF and HF (LF/HF ratio), which reflects the dependence on both components on autonomic activity; 6) normalized LF (LFnu [LF/(PSD – VLF) × 100]) and normalized HF (HFnu [HF/(PSD – VLF) × 100]), with the participation throughout the frequency spectrum expressed as a percentage (%).

Statistical analysis

Analyzing the data distribution in the studied groups, to avoid the requirement for a normal distribution, we decided to apply a distribution-free test suitable for a small population. Differences in paired data were analyzed with Wilcoxon’s test, and differences in unpaired data were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test. Depending on the distribution type, the significance of intragroup differences was verified with two-way ANOVA followed by the Kruskal-Wallis post-hoc test, which was performed to examine the differences between patients and the control group when data normality was not present. The association between EGG and HRV was evaluated by analyzing the relationship between EGG parameters (percentage of normogastria, tachygastria, bradygastria, and dysrhythmias, PDF, PDP, and APSWC) and HRV analysis indices. The correlation between analyzed data was determined with Spearman’s test. TIBCO Statistica for Windows, version 13.3 PL (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA, Jagiellonian University license) software was used for statistical analyses. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, median (Me) and min-max values. The threshold of statistical significance for all the tests was set at p < 0.05.

Results

All 76 participants included in the study had normal liver, kidney, and thyroid function, and the clinical values of mean corpuscular volume and red blood cell distribution width were within the reference range. None of the patients and controls had anemia. Inflammation was excluded based on low C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (< 5 mg/l). Although mean serum CRP levels were significantly higher in dyspepsia patients than in controls, the results were within the reference range in both groups. Three patients with dyspepsia had an elevated CRP. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are presented in Table I.

Preprandial vs. postprandial analysis

EGG

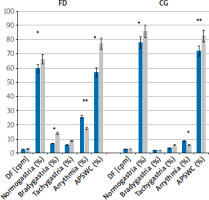

In the fasting state, patients with dyspepsia had a significantly lower percentage of normogastria (51.62 ±19.62 vs. 79.13 ±14.12%; p = 0.004) and a lower APSWC (51.11 ±13.25 vs. 69.22 ±14.18%, p = 0.001) compared to the control group. After a meal in patients with dyspepsia, the percentage of bradygastria increased from 5.6 ±3.1 do 12.2 ±6.3%; p = 0.01. The APSWC increased but did not reach the value of the control group (77.3 ±14.1%). The increase in the amplitude of slow waves after a meal was lower (on average by 49%) than in the control group (on average by 215%, p = 0.0001), which indicates a disturbance of the gastric motor function (Figures 1, 2, Table II).

Figure 1

Changes of EGG parameters in response to the standard meal in dyspepsia and control groups

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001 – significant differences in response to the meal (Wilcoxon’s test), p < 0.05; DF – dominant frequency, APSWC – average percentage of slow wave coupling.

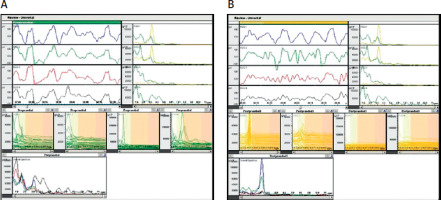

Figure 2

Original EGG results in patient with dyspepsia (women, age 52). A – preprandial state, B – postprandial state. Disturbances of gastric myoelectric activity in preprandial state (green line) after meal increase amplitude and regularity in channels 1 and 2, but disturbances in antral area of the stomach (channels 3 and 4) remained

Table II

Parameters of gastric myoelectric activity obtained from multichannel electrogastrography in patients with dyspepsia and in the control group

ANS – HRV

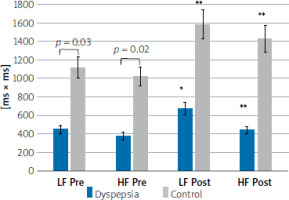

At rest, the parameters of HRV spectral analysis (high (HF) and low frequency (LF)) were significantly lower in patients with dyspepsia than in the control group (LF; p = 0.03; HF; p = 0.01). Postprandially, patients with dyspepsia showed an increase in both LF (p = 0.03) and HF (p = 0.02) indices, similar to the control group, but the parameter values were lower compared to the control group. Particularly, the HF index was lower after a meal compared to the control group (259.76 vs. 351.42 ms2; p = 0.047) (Figure 3, Table III).

Figure 3

Changes of selected HRV parameters (LF, HF) in response to the meal in dyspeptic patients and control group

*p = 0.001; **p = 0.02 in response to the meal (Wilcoxon’s test); Pre – preprandial state, Post – postprandial state, LF – lowfrequency (0.04–0.1 Hz), HF – high-frequency (0.15–0.4 Hz).

Table III

Parameters of frequency domain analysis of HRV in patients with dyspepsia and in the control group

* Significant differences in response to the meal (Wilcoxon’s test), p < 0.05; NS – not significant, PSD – power spectral density in the range of total power (0.0033-0.4 Hz), VLF – very-low frequency (0.0033–0.04 Hz), LF – low-frequency (0.04–0.1 Hz), HF – high-frequency (0.15–0.4 Hz), LFnu – normalized LF [LF/(PSD–VLF)*100], HFnu – normalized HF [HF/(PSD–VLF)*100]. BPV – blood pressure variability, HRV – heart rate variability.

Correlation between EGG and HRV parameters

In the pre-prandial state, the average slow wave coupling negatively correlated with the preprandial HF (R = –0.33; p = 0.038) and positively correlated with the preprandial LF (R = 0.33; p = 0.038) in FD patients, but in control group APSWC was positively correlated with HF (R = 0.34; p = 0.048). The LF/HF ratio was positively associated with APSWC (R = 0.335; p = 0.027) in FD patients, while in the control group it was negatively associated (R = –0.41; p = 0.035).

After a meal, APSWC was negatively correlated with HF (R = –0.32; p = 0.046) and positively correlated with postprandial LF (R = 0.32; p = 0.046) in FD patients, but in the control group APSWC was positively correlated with HF (R = 0.41; p = 0.033). The LF/HF ratio was positively associated with APSWC (R = 0.34; p = 0.032) in FD patients, whereas it was negatively associated in the control group (R = –0.41; p = 0.036).

Discussion

DGBI, previously named functional gastrointestinal disorders, are leading diagnoses in gastroenterological settings. Among DGBI, the most common are functional dyspepsia (FD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [18]. According to the Rome IV criteria, dyspepsia is defined by the presence of any of the four following symptoms: 1) postprandial fullness, 2) early satiation, 3) epigastric pain, or 4) epigastric burning. These symptoms have to be severe enough to interfere with daily activities, occur at least 3 days per week over the last 3 months, with an onset at least 6 months previously [18]. Based on the clinical presentation, FD can be classified into two subgroups: epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) and eating-related postprandial distress syndrome (PDS).

The pathophysiology of FD is not fully understood. Due to multifactorial pathomechanisms underlying DGBI, the diagnosis and management of these elusive disorders seems to be unsatisfactory [18]. So far, gastroduodenal motor and sensory dysfunction, gut-brain axis dysregulation, impaired mucosal integrity, low-grade inflammation, and impaired immune activation have been taken into consideration [18].

Among potential causes of FD, motor abnormalities including delayed gastric emptying and impaired distribution of gastric contents are observed [19]. These abnormalities comprise: a) altered gastric fundus accommodation, b) abnormally distended ventricular antrum, c) antral hypomotility, and/or d) abnormal duodenal motility. However, data on the correlation between these alterations and symptoms are limited [18, 19]. A trend was observed associating more frequent delayed gastric emptying with symptoms such as early satiation, bloating, postprandial fullness, nausea, and vomiting [20]. Also gastric and duodenal hypersensitivities to luminal distension, acid, lipids, and other stimuli were described [18]. EDS patients are characterized by fasting and postprandial gastric hyper-mechanosensitivity, while PDS patients typically exhibit decreased gastric compliance. On the other hand, rapid gastric emptying has also been described in FD patients and may be a contributing factor [21].

Another mechanism underlying FD is altered visceral sensitivity with both mechanical and chemical hypersensitivity [22]. Additionally, brain processing of sensory signals appears to be impaired in FD [23].

In our study, we focused on myoelectric activity and impairment of the ANS in patients suffering from FD. In the fasting state in patients with dyspepsia a lower percentage of normogastria was observed compared to the control group. Previous studies by Al Kafee et al. and Kayar et al. reported a higher incidence of gastric dysrhythmias and delayed gastric emptying in FD and gastroparesis [23, 24]. Also, Leahy et al. found that gastric arrythmias were present in 36% of FD patients, which was significantly higher than in the control group [25]. In our study, in the FD group, preprandial bradygastria was more frequent compared to the CG, though this difference was not statistically significant. However, a postprandial increase in bradygastria was observed in FD in comparison to the control group. This observation supports the results of Al Kafee et al., who also reported higher levels of bradygastria in FD patients [23, 24].

Dyspepsia is a common complaint among patients with scleroderma. McNearney et al. reported significantly higher rates of bradygastria and significantly lower gastric slow-wave regularity in comparison to the control group, in both preprandial and postprandial conditions [26]. Similarly, changes of electrogastrography were found in celiac patients. The results showed reduced responsiveness of the autonomic nervous system to water ingestion, which may lead to disturbances of gastric myoelectrical activity, and which depends on baseline autonomic activity [27].

In our study, preprandial and postprandial differences in DP and DF were not statistically significant, which is partially consistent with a study by Lin et al. [28]. They observed that in 60% of FD patients the postprandial dominant power did not increase along with gastric slow waves and dysrhythmias [28]. On the other hand, Al Kafee et al. obtained different results, in which they found that preprandial DF and DP levels were lower. Additionally, the percentage of bradygastria was higher in the FD group, whereas DF and DP levels were lower in comparison to the control group [23]. Lim et al. observed that the most common abnormalities in EGG were dysrhythmia, low EGG power ratio, and a high instability coefficient [29]. In contrast, Holmvall et al. found no differences in EGG parameters between patients and healthy volunteers, but they evaluated a small group of patients [30]. Disturbances of gastric myoelectric activity can lead to the dysfunction of gastric motility. Gastric myoelectric activity includes slow waves (referred to as electrical control activity) and spike potentials associated with electrical response activity [31]. Therefore, we can use EGG as a reliable measurement method, recording gastric slow waves and parameters derived from spectral analysis, which provide clinically relevant information about gastric motility, especially when slow wave coupling and the postprandial/preprandial ratio of the slow wave amplitude are used [31, 32].

Pasricha et al. concluded that FD and gastroparesis (GP) may be part of the same spectrum of neuromuscular abnormalities with similar symptoms, altered gastric emptying in test or microscopic changes with depletion of Cajal cells and CD206+ macrophages [33]. Similar results in EGG analysis observed in FD and GP patients suggest a common pathogenesis.

This study was undertaken to evaluate the pathophysiological importance of changes in gastric myoelectric activity and ANS activity in patients with FD. Our study assessed HRV to evaluate ANS dysfunction both at rest and after a standardized meal. Our main finding showed that, in FD patients, resting spectral HRV parameters were lower than in the control group, and the response to the meal stimulation was blunted, with lower activation of the parasympathetic component of ANS in comparison to the healthy volunteers.

Previously described evaluations of the ANS activity in FD was based mostly on small groups or case series [16, 22, 34]. A few studies have attempted to use spectral analysis of HRV to evaluate the sympathetic and parasympathetic function after meal ingestion in adults, and the results are conflicting. Lipsitz et al. observed a significant increase of power in the low-frequency band (LF: 0.01–0.15 Hz) in healthy young volunteers after mixed meal ingestion [35]. Our study confirmed these results; we observed that, postprandially, in patients with dyspepsia LF and HF HRV indices increased, similar to the control group, but the parameter values were lower compared to the control group. However, two recent studies in adults showed that the postprandial sympathovagal balance was significantly increased and lasted for at least 1 h, primarily due to diminished vagal activity, while the postprandial change in LF power was not statistically significant [36].

To our knowledge, simultaneous recordings of electrocardiography (ECG) and EGG in dyspepsia patients have been performed in only three previous studies, which investigated the relationship between postprandial EGG parameters and HRV parameters following ingestion of liquids [16, 37, 38]. Zhu et al. found that the autonomic dysfunction was characterized by a decline of vagal activity in patients with FD compared with healthy controls [39]. It is well known that the parasympathetic nerve stimulates, while the sympathetic nerve inhibits, motor activity of the stomach. The increased gastric vagal efferent activity results in enhanced gastric accommodation and improved gastric pace-making activity (slow wave). Additionally, the vagal nerve plays a crucial role in the “anti-inflammatory reflex”; for this reason, reduced vagal efferent activity may lead to an impaired vagal efferent anti-inflammatory response, which may potentially contribute to the increased inflammation in functional dyspepsia [40]. These theories are supported by studies which revealed that the anti-inflammatory effects of acupuncture stimulation (decreased level of IL-6) and vagal nerve stimulation might be mediated through the vagal nerve system modulating inflammatory reactions [39, 41].

Additionally, our study showed that the preprandial and postprandial correlation between LF, HF, LF/HF ratio, and APSWC in FD patients differed from those in the control group. The EGG – APSWC was negatively correlated with the HF-HRV, and positively with LF-HRV and LF/HF ratio in FD patients, but in the control group APSWC was positively correlated with HF-HRV and negatively associated with LF-HRV and LF/HF ratio. These differences may result from excessive activation of the sympathetic ANS component and/or reduced parasympathetic component activity, which leads to dysregulation of the gastric electrical rhythm. Greydanus et al. [42] found evidence of disorders in extrinsic neural control in FD patients, with or without associated abnormal gastrointestinal transit, while Gilja et al. [43] suggested a relation between low efferent vagal tone and antral dysmotility in these patients. Based on the observations so far, we can conclude that functional dyspepsia is a heterogeneous disorder. Abnormal transit is sometimes associated with disorders of extrinsic neural control, but the latter also occurs in patients with normal transit. Increased perception of intraluminal stimuli in those with normal transit suggests a disturbance in afferent function. A meal can alter ANS function, typically triggering an increase in parasympathetic nervous system activity (Figure 2). However, this response did not occur in approximately 40% of the FD patients [42].

Furthermore, postprandial sympathetic nerve activity over 120 min was also not seen in approximately 44% of FD patients [44]. These findings could signify a decline in responsiveness to external ANS activity stimuli. This confirmed our study observation, showing a decrease in HRV parasympathetic parameters and association with sympathetic dominant in sympathovagal balance of ANS 1 h after a meal.

Tominaga et al. suggest that declines in ANS responsiveness may be involved in the appearance of symptoms such as postprandial fullness. Additionally, there is a decline in the ability to recover to preprandial levels of ANS balance in response to meals. The meals can modify the function of ANS, but to maintain homeostasis, it must recover to preprandial levels. The authors suggested a decline in ANS adaptability and its role in development of dyspeptic symptoms in dyspepsia patients [44].

Due to the fact that the vagus nerve plays an important role in the regulation of GI tract function, other studies indicate that in the pathophysiology of dyspepsia the impairment of the vago-vagal reflex control of the upper GI tract may play an important role [40]. Lunding et al. [45] suggested that FD may arise from either inadequate vagal sensory stimulation—supported by studies of Holtmann et al. and Greydanus et al. [42, 46] – or from excessive or hypersensitive vagal sensory stimulation as a consequence of either insult or injury, including abnormal acid challenge [47]. A review by Hui Lu et al. proposed in the pathophysiology of FD the following mechanisms: enhanced vagal signaling in response to distension (increased vagal afferent sensitivity); vagal afferent sensation of gastroduodenal nutrients (increased levels and hypersensitivity), hormones and low pH; altered vagal signaling in response to gastroduodenal inflammation; and reduced vagal efferent signaling in modulation of gastrointestinal motility, secretion and inflammation [40].

In clinical practice, most investigated patients with FD have been treated with or tried anti-acid secretory medications by the time they see a gastroenterologist. The empiric choice follows a “hunch”, a perception by the clinician of the underlying cause of the patient’s symptoms. Indeed, it may be feasible to select a prokinetic for postprandial distress or a central neuromodulator for epigastric pain syndrome.

Conclusions

The postprandial parasympathetic response was reduced in patients with FD compared to the control group. The decreased reactivity of ANS in functional disorders contributes to gastric myoelectric dysfunction as manifested by clinical signs of dyspepsia. Gastric myoelectrical activity and involvement of the ANS seem to play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of FD [23]. Our study establishes the role of EGG and HRV testing as a useful non-invasive test for analyzing the impaired ANS and gastric myoelectric activities among FD patients in comparison to healthy volunteers. This knowledge is important in clinical practice. Due to this, pharmacotherapy with prokinetics or a central neuromodulator has a crucial role, beyond the proton pump inhibitors, in FD therapy. Modulation of ANS activity or gastric myoelectric activity should be considered as a potential new therapeutic approach to FD treatment. We believe that the modulation of vagal and sympathetic ANS stimulation may be helpful to restore normal GI function.

The British Gastroenterology Recommendations recommend proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and, in some cases of FD, prokinetics as a first line treatment. PPIs have strong recommendation and high quality of evidence. Regarding prokinetics, itopride and mosapride are strongly recommended, while tegaserod has moderate quality of evidence, and acotiamide has a weak recommendation and low quality of evidence [1].

For the second line of FD treatment, the British Gastroenterology Society recommends tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) to be used as gut–brain neuromodulators (recommendation: strong, quality of evidence: moderate) whereas other drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and 5-hydroxytryptamine-1A agonists except for tandospirone, so far do not have strong recommendations nor high quality of evidence [1].

Our study adds more information to the pathogenesis of FD, although it has some limitations. These include the technical limitations of EGG: the relatively low signal-to-noise ratio of the signal, and the applicability and reproducibility of the method, dependent on technological developments, appropriate equipment settings, the development of new amplifiers, and signal quality.