Introduction

A surgical site infection (SSI) is defined as ‘an infection that occurs after surgery in the part of the body where the surgery took place’ or as ‘an infection that occurs within 30 days after the operation’ [1,2]. These infections can be superficial (skin) or deep incisional, involving subcutaneous tissues, organs, cavities, or implanted material. Surgical wounds can be infected by the patient’s skin, mucous membrane or visceral endogenous flora. Exogenous sources include healthcare personnel, surgical instruments, and the operating room environment. Accordingly, the most commonly isolated bacteria are Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), Enterobacteriaceae, enterococci and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [3].

Although healthcare facilities apply strict prophylaxis measures, SSIs remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in surgical patients. SSIs are considered as one of the most common nosocomial infections [4] leading to longer hospital care and often requiring complicated and prolonged antibiotic treatment [5]. The high prevalence of SSIs is logically associated with high amounts of antibiotics used in surgery departments for both prophylaxis and treatment, thus serving as an important source of antimicrobial resistance. The latter is currently accepted as the most critical health problem with millions of related deaths annually [6]. Measures to address appearance and spread of resistant microbial strains in hospitals are numerous and well-known but all surveillance programs rely on regular bacterial isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Aim of the work

Currently, little is known about the prevalent bacterial species associated with surgical site infections in Bulgaria and their antibiotic sensitivity pattern. The available information is, as of this writing, ten years old, and nothing is known about the actual situation in the country [7-9]. In this context, the purpose of the study was to evaluate the incidence, bacteriological profile and antimicrobial resistance of SSI pathogens isolated in one of the biggest hospitals in North-Eastern Bulgaria – the Military Medical Academy in Varna.

Material and methods

The current study is a retrospective analysis of anonymized laboratory results. From January 2019 to December 2021, a total of 957 samples obtained from surgery sites were examined as part of the regular diagnostic procedures for patients admitted in surgical units (Surgery Department, Urology Department, Gynecological Department, and Orthopedics and Traumatology Department) of the Military Medical Academy, Varna. Consecutive samples from one patient were counted as unique samples when there were different pathogens isolated; if the same bacterium was isolated, the consecutive samples were excluded from the analysis.

After collection, wound swabs were inoculated on Blood Agar, MacConkey`s Agar, Sabouraud Dextrose Agar or Tryptone Soya Broth (BB-NCIPD Ltd., Bulgaria and Oxoid Ltd., UK). Organisms were identified by using manual biochemical tests (BB-NCIPD Ltd., Bulgaria) and the BD BBL ‘Crystal’ identification system (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA). The antibiotic susceptibility pattern of isolates was determined by the Kirby-Bauer’s disk diffusion method on Mueller Hinton Agar (Oxoid Ltd., UK). All antibiotic disks were purchased from Oxoid Ltd., UK and used in the recommended concentration following the actual EUCAST guideline for each year of analysis (EUCAST 2019, 2020 and 2021, respectively). Susceptibility only to colistin was determined with a microdilution test – Mikrolatest (Erba Lachema, Czech Republic). Results were interpreted following corresponding EUCAST guidelines.

The confidence intervals (CI) for the proportions of different isolates were calculated with the Wilson score interval in R project for statistical computing (version 4.0.4/2021-02-15).

Results

A total of 463 isolates were obtained from 957 surgical site samples collected for the three years of the study. Table 1 shows detailed information on the aetiologic structure and number of bacteria isolated from surgical wounds for the entire study period. The most common isolates were CoNS, followed by E. coli and Enterococcus spp.

Table 1

Frequency of bacterial isolates from surgical site samples in Military Medical Academy,

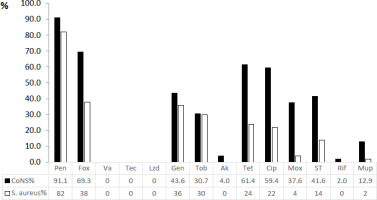

CoNS were more resistant than Staphylococcus aureus to all antimicrobials tested (Figure 1). The highest levels of resistance were against penicillin (91.1% and 82% for CoNS and S. aureus, respectively), while methicillin resistance was 69.3% in CoNS and 38% in S. aureus. The most active antibiotics against staphylococcal isolates were vancomycin, teicoplanin and linezolid with 100% activity (Figure 1). In addition, S. aureus was also fully sensitive to amikacin and rifampicin.

Figure 1

Antimicrobial resistance pattern of coagulase negative staphylococci (in black) and Staphylococcus aureus (in white) (presented as % = number of resistant isolates/total number of isolates)

Notes: Pen – penicillin, Fox – cefoxitin, Va – vancomycin; Tec – teicoplanin, Lzd – linezolid, Ery – erythromycin, Clin – clindamycin, Gen – gentamicin, Tob – tobramycin, Ak – amikacin, Tet – tetracycline, Cip – ciprofloxacin, Mox – moxifloxacin, ST – sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, Rif – rifampicin, Mup – mupirocin.

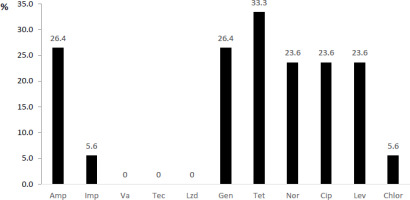

In enterococcal isolates, the resistance rate was the highest against tetracycline (33.3%), followed by ampicillin, gentamicin and quinolone antibiotics (Figure 2). Similarly, to staphylococci, glycopeptide antibiotics and linezolid were the most effective drugs against Enterococcus spp.

Figure 2

Antimicrobial resistance pattern of enterococci (presented as % = number of resistant isolates/total number of isolates)

Notes: Amp – ampicillin, Imp – imipenem, Va – vancomycin, Tec – teicoplanin, Lzd – linezolid, Gen – gentamicin, Tet – tetracycline, Nor – norfloxacin, Cip – ciprofloxacin, Lev – levofloxacin, Chlor – chloramphenicol.

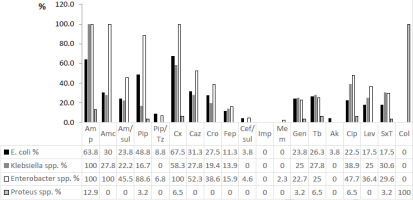

From enteric bacteria, Genus Enterobacter was the most resistant to all tested antibiotics followed by Klebsiella spp. (Figure 3). For the crucial third-generation cephalosporins, Enterobacter spp. showed up to 52.3% resistance and Klebsiella spp. up to 27.8%. Lower levels of resistance were observed in E. coli isolates (21.3%). Colistin, imipenem and meropenem preserved their activity at almost 100%.

Figure 3

Antimicrobial resistance pattern of enterobacteria* (presented as % = number of resistant isolates/total number of isolates)

Notes: *the innate resistance of Enterobacter spp., Proteus spp., Klebsiella spp. is not excluded from the chart; Amp – ampicillin, Amc – amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, Am/sul – ampicillin/sulbactam, Pip – piperacillin, Pip/Tz – piperacillin/ tazobactam, Cx – cefuroxime, Caz – ceftazidime, Cro – ceftriaxone, Fep – cefepime, Cef/sul – cefoperazone/sulbactam, Imp – imipenem, Mem – meropenem, Gen – gentamicin, Tb – tobramycin, Ak – amikacin, Cip – ciprofloxacin, Lev – levofloxacin, SxT – sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, Col – colistin.

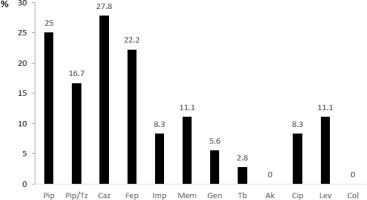

The results of drug susceptibility tests in P. aeruginosa isolates showed the highest resistance rate against beta-lactams – piperacillin, ceftazidime and cefepime and the lowest – against colistin and amikacin (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (presented as % = number of resistant isolates/ total number of isolates)

Notes: Pip – piperacillin, Pip/Tz – piperacillin/tazobactam, Caz – ceftazidime, Fep – cefepime, Imp – imipenem, Mem – meropenem, Gen – gentamicin, Tb – tobramycin, Ak – amikacin, Cip – ciprofloxacin, Lev – levofloxacin, Col – colistin.

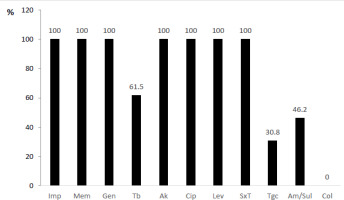

In the current study, thirteen A. baumannii isolates were found, and all of them showed 100% resistance to imipenem, meropenem, gentamicin, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (Figure 5). Only the activity of colistin was completely preserved among the isolates.

Figure 5

Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Acinetobacter baumannii (presented as % = number of resistant isolates/ total number of isolates)

Notes: Imp – imipenem, Mem – meropenem, Gen – gentamicin, Tb – tobramycin, Ak – amikacin, Cip – ciprofloxacin, Lev – levofloxacin, SxT – sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, Tgc – tigecycline, Am/sul – ampicillin/sulbactam, Col – colistin.

Discussion

We found that the most common bacterial agents causing infections of surgical sites were CoNS, E. coli, Enterococcus spp., and S. aureus. Most of the previous studies in different countries also found the same etiological agents – Enterobacteriaceae, staphylococci, enterococci and non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli represent practically all isolates in surgical site samples from surgical patients. However, there are some local differences in the leading pathogens: the majority of the studies conclude that S. aureus [1,9-11] or E. coli [7,12] are the most common bacteria causing SSI in surgical departments. Interestingly, our results showed CoNS to dominate over both S. aureus and E. coli, counting for more than 20% of all isolates.

Furthermore, CoNS were more resistant to all antimicrobials tested (including cefoxitin, to which the resistance rate was almost two times higher) than S. aureus. Our results differ from the data of a systematic review [3], which reported higher rates of penicillin, tetracycline and vancomycin resistance in S. aureus than in CoNS and an almost equal methicillin resistance. Fortunately, the activity of critically important antibiotics, such as vancomycin, teicoplanin and linezolid was preserved at 100% in both CoNS and S. aureus (as well as in Enterococcus spp).

Among the isolated gram-negative bacteria, E. coli dominated, but other enterobacteria (Enterobacter spp., Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp.) were also relatively frequent. In general, they account for 41% of all surgical isolates. The family Enterobacteriaceae is considered critical for the emergence of the antibiotic resistance with emphasis on third-generation cephalosporins. We found 52.3% of Enterobacter isolates, 27.8% of Klebsiella spp. and 21.3% of E. coli to be resistant to ceftazidime, rates which we consider significant although markedly lower than those found in similar studies [13,14]. We also reported a highly preserved sensitivity of all enterobacterial isolates towards colistin (except Proteus spp. which is naturally resistant), imipenem, meropenem, amikacin and piperacillin/tazobactam.

P. aeruginosa isolates were also resistant to ceftazidime and 13.3% were resistant to piperacillin/ tazobactam [15] but were significantly lower than that reported by Ali & Al-Jaff, who found 100% resistance to ceftazidime, and by Worku et al., who found 66.6% resistance to ceftazidime [10,14]. The carbapenem resistance was also detected among P. aeruginosa isolates – 11.1% and 5.6% for meropenem and imipenem, respectively – numbers similar to the widely accepted proportion of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa [16].

Finally, the resistance of A. baumannii is worth a discussion. This bacterium efficiently evades many of the antimicrobial drugs and its incidence in health care units is increasing world-wide [17]. Accordingly, we found all isolates resistant to most of the tested antibiotics. The sole available treatment option with 100% efficiency was colistin and to some degree tigecycline, ampicillin/sulbactam and tobramycin. This result differs drastically from the previous reported resistance – Worku et al. reported 65.9% and 84.2% resistance rate to imipenem and meropenem respectively, Ali & Al-Jaff reported 50% resistance to carbapenems and Monnheimer et al. – 49% carbapenem resistance [10,14,18].

The current study has some limitations that have to be stated. First, this was a retrospective, observational and single-center study. Second and more important was the lack of additional information about patients. Only the microbiological aspects of the collected samples were considered. This could impact the conclusions, as important information for risk and prognostic factors such as age, comorbidities, clinical presentation and infection outcome are missing. Third, our work is a local analysis limited to one hospital in Varna, Bulgaria. This could affect the global importance of the findings, as antimicrobial resistance of bacteria differs significantly in different geographic areas.

Conclusions

The etiological structure of surgical site infections in the Military Medical Academy, Varna, was comparable to that found in other studies, with a clear prevalence of coagulase-negative staphylococci and enteric bacteria. We consider glycopeptides and linezolid as still efficient treatments against gram-positive bacteria and colistin against gram-negative bacteria. Strict and active antimicrobial resistance surveillance should be adapted to a larger extent to prevent the emergence of resistant strains.