Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a method used in clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract and pancreas diseases. Due to the invasive nature of the procedure, the incidence of postoperative complications ranges from 10% to 12%, with an overall mortality rate of up to 1.4% [1].

The most common complications of ERCP include: acute pancreatitis (1.6–15%, mortality rate 0.1–0.7%) [2], cholangitis (0.5–3.0%, mortality rate 0.1%) [3], cholecystitis (0.5–5.2%, mortality rate 0.04%) [4], bleeding (0.3–9.6%, mortality rate 0.04%) [5], duodenal perforation (1%, mortality rate 8–23%) [6], and other complications such as arrhythmia, aspiration pneumonia, liver abscess, subcapsular liver hematoma, paralytic ileus, pneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum, among others [7].

The prevalence of gallstone disease during pregnancy ranges from 12% to 30% [8], and complications of choledocholithiasis occur in a ratio of 1200 : 1 cases [9]. The increase in progesterone levels during pregnancy leads to delayed gallbladder emptying, promoting bile stasis and the development of cholesterol stones in the gallbladder [8, 9].

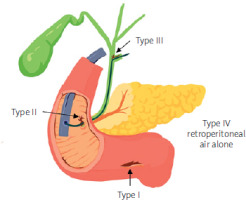

Stapfer et al. (2000) classified gastrointestinal perforations following ERCP according to anatomical features into 4 types (Table I) [10]. The incidence of these types is as follows: type II – 58%, type I – 18%, type III – 13%, type IV – 11% [11]. Risk factors for perforation following ERCP include advanced age, technical factors, the complexity and duration of sphincterotomy, periampullary diverticulum of the duodenum, and a dilated stenosis of the terminal part of the common bile duct [10, 11] (Figure 1).

Table I

Classification of perforation after ERCP proposed by Stapfer et al. [10]

Figure 1

Typical manifestations of perforation after ERCP proposed by Stapfer et al. (author’s project)ć

Choledochal cyst (CC) is a rare congenital anomaly of the biliary tract, primarily affecting women, with a female-to-male ratio of 4 : 1 or 3 : 1 [12]. Diagnosing this condition in pregnant women is challenging, as it is infrequently observed in adults and is further complicated by changes in gallbladder function during pregnancy. Choledochal cysts pose a threat to both the mother and the fetus, with the main expected complications being fetal loss and premature labor. It is important to note that choledochal cysts are congenital anomalies and are not classified into functional or organic types [12].

The Todani classification (1977) identifies five types of choledochal cysts. Type I, which accounts for 50–85% of all cases, is the most common. This type involves dilation of the common bile duct, which is further subdivided into subtypes IA, IB, and IC. These cysts can be cystic or fusiform and are often the only lesions within the biliary tract. Type I CC is most commonly found in pregnant women, constituting 73.8%, followed by type IV [12]. Choledochal cysts are most often diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy when the enlarging uterus reaches the upper abdomen. The incidence of cyst rupture is 7.1%, with most cases reported in studies prior to 1990. The mortality rate among women with choledochal cysts is 7.2% [13].

The most common symptoms of choledochal cysts in pregnant women include: epigastric/right upper quadrant pain (80%), jaundice (59%), fever (30.1%), the classic triad of CC (abdominal mass, jaundice, pain) (50.5%), and Charcot’s triad (28.8%) [14].

Some data show that pregnancies with choledochal cysts were concluded as follows: vaginal delivery (39%), cesarean section (42%), and abortion (13%). Furthermore, 48% of pregnancies continued for 36 weeks or longer, while 39% lasted less than 35 weeks [14].

Some authors have reported the appearance of retroperitoneal air after ERCP in an asymptomatic form in up to 29% of cases [15].

Case report

Clinical case: A 48-year-old pregnant woman was hospitalized at the regional hospital for inpatient treatment due to mechanical jaundice. For the past 2 weeks, she had been experiencing pain, severe pruritus, and dark urine. The total bilirubin level was 35.6 mmol/l. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) of the abdominal organs (12/08/2022) revealed stones in the lower third of the common bile duct, measuring 12.0 × 10.0 × 5.5 mm, 15.0 × 7.0 mm, and 8.0 × 5.2 mm, as well as a choledochal cyst measuring up to 22.3 mm in diameter.

A telemedicine consultation with specialists from National Scientific Center of Surgery (NSCS) was conducted, and ERCP with choledocholith extraction was recommended. The patient was transferred to the NSCS for further treatment.

Anamnesis vitae: The patient has a history of two surgical procedures: cesarean section and laparotomy with appendectomy for “acute destructive appendicitis, diffuse peritonitis”. This pregnancy is her second and was achieved through in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Physical examination: The general condition was moderately severe, with normal nutritional status and a normosthenic build. The patient’s height was 162 cm, weight 70 kg, and BMI 26.67 kg/m2. The skin showed jaundice with scratch marks. No peripheral edema was observed. Body temperature was 36.4°C. Vesicular breath sounds were noted in the lungs with no wheezing. The heart sounds were muffled and rhythmic, with blood pressure 120/80 mm Hg and a pulse of 68 beats per minute. The tongue was moist with a slightly white coating. The abdomen was enlarged due to pregnancy, symmetrical, soft, and non-tender on palpation. No peritoneal signs were present. The urine was dark brown, and urination was free and painless. The stool was regular, well-formed, and of normal color.

Laboratory results on admission: complete blood count (CBC): white blood cells (WBC) (leukocytes): 11.40 × 103/µl, right blood cells (RBC) (erythrocytes): 3.80 × 106/µl, hemoglobin (HGB): 122.0 g/l, hematocrit (HCT): 36.0%, platelets (PLT): 227.0 × 103/µl.

Urine analysis (UA): specific gravity (SG) – > 1.005, pH (acidity) – 7.00, COLU (color) – dark, volume – 100 ml, transparency – clear, urobilinogen – 3 µmol/l, microalbumin – 10 mg/l, creatinine – 0.90 µmol/l.

Biochemical blood test: alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 25.60 U/l, aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 25.90 U/l, creatinine – 58.00 µmol/l, total bilirubin – 47.10 µmol/l, direct bilirubin – 44.60 µmol/l, total protein – 59.40 g/l, glucose – 5.99 mmol/l, urea – 3.40 mmol/l, alpha-amylase – 1350.0 U/l.

Coagulation profile: prothrombin time (PT) – 10.70 s, thrombin time (TT) – 15.4 s, prothrombin index (PT%) – 132.0%, PT international normalized ratio (INR) – 0.80, fibrinogen – 3.45 g/l, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) – 23.0 s.

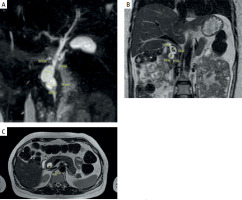

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): Intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts were dilated; the hepatic duct was 3.5 mm on the right and 3.2 mm on the left. Separate entry points of the segmental ducts S3 and S6 at the confluence. The middle third of the common bile duct was dilated to 6.5 mm, and the lower third was cystically dilated to 22.3 mm. The walls were unevenly thickened, particularly in the lower third, and the lumen was heterogeneous. Type I according to Todani classification. Stones were identified in the lower third of the common bile duct, measuring 12.0 × 10.0 × 5.5 mm and 15.0 × 7.8 × 5.2 mm (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdominal organs and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), showing a choledochal cyst and stones indicated by arrows: A – MRCP: In the distal third of the common bile duct, cystic dilatations are identified (choledochal cyst type I according to Todani) . B – Abdominal MRI (T2-weighted image, coronal slice): In the distal third of the common bile duct, stones are observed within the cystic dilatation. C – Abdominal MRI (T2-weighted image, axial slice): cystic dilatation of the common bile duct (choledochal cyst type I according to Todani) with stones inside

Clinical case continued: Given the presence of choledocholithiasis and mechanical jaundice, the decision was made to perform an endoscopic procedure: endoscopic papillosphincterotomy (EPST), ERCP, and choledocholith extraction under general anesthesia.

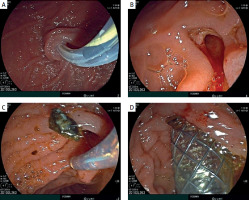

On 13th December 2022: During the endoscopy, the major duodenal papilla (MDP) was not enlarged. The common bile duct (CBD) was catheterized: the proximal part measured up to 1.0 cm in diameter, while the middle and lower thirds were cystically dilated to 2.5–3.0 cm, forming two cavities. Two shadows, measuring 1.1–1.3 cm in diameter, were observed in the lumen of the CBD in the distal part (Figure 3). Endoscopic papillosphincterotomy (EPST) was performed up to 0.7 cm with additional balloon dilation to 1.1 cm. The stones were extracted.

Figure 3

Fistulography during ERCP: visualization of the catheter in the common bile duct (choledochus)

During the procedure, subcutaneous emphysema of the chest, neck, and face was identified, suggesting a possible rupture of the choledochal cyst wall and the entry of air from the abdominal cavity into the mediastinum. To close the rupture of the choledochal cyst, it was decided to place an endobiliary stent. A metallic fully covered endobiliary stent, 6.0 cm in length, was placed in the CBD. After the stent placement, bile began to flow through the stent (Figure 4). After the placement of the endobiliary stent, no further progression of the subcutaneous emphysema was noted.

Figure 4

A – Catheterization of the common bile duct with a papillotome over a guidewire. B – Endoscopic papillosphincterotomy up to 0.7 cm with additional balloon dilation. C – Choledocholithotripsy. D – Insertion of a self-expanding metal stent

A chest X-ray revealed a right-sided pneumothorax. The thoracic surgeon performed pleural drainage according to the Bülau method.

After the surgery, the patient was placed in the intensive care unit (ICU), where, in the early postoperative period, acute post-catheterization pancreatitis developed, with an increase in amylase levels to 842.0 U/l.

In the ICU, the patient received the following medications (Table II): Three days after the procedure, a follow-up chest X-ray and ultrasound were performed, and the pleural drainage tube was removed. The patient was allowed to eat on the fourth day after the clinical and laboratory resolution of acute pancreatitis. On the fifth day after surgery, the subcutaneous emphysema in the face and neck areas regressed, but it remained in the chest area.

Table II

Medications administered in the ICU during the early postoperative period

On the eighth day, following improvement in her condition, the patient was transferred to the surgical department.

Results

Results of tests over time in the ICU presented in Tables III–VII.

Table III

Dynamic changes in the complete blood count

Table IV

Dynamic changes in the biochemical blood analysis

Table V

Dynamic changes in the general urine analysis

Table VI

Dynamic changes in the coagulation profile analysis

Table VII

Dynamic changes in C-reactive protein levels

| Day | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-reactive protein [s] | 154.5 | 119.5 | 102.1 | 88.5 | 74.9 |

Clinical case conclusion: In the surgical department, conservative therapy continued along with daily monitoring of the fetus’s condition. Over time, the patient’s condition improved, and the subcutaneous emphysema in the chest area fully resolved. After stabilizing her general condition and normalizing her lab results, she was discharged on the seventeenth day for further outpatient treatment.

Discharge laboratory results: CBC: WBC – 8.90 × 103/µl, RBC – 3.47 × 106/µl, HGB – 110.0 g/l, HCT – 32.50%, PLT – 447.0 × 103/µl.

UA: SG – > 1.010, pH – 6.00, COLU (color) – straw-yellow, urine volume – 100 ml, urine clarity – clear, urobilinogen – 1 µmol/l, microalbumin – 3 mg/l, creatinine – 0.30 µmol/l, protein – negative.

Biochemical blood analysis (BCA): ALT – 30.70 U/l, AST – 26.50 U/l, creatinine – 54.00 µmol/l, total bilirubin – 19.50 µmol/l, direct bilirubin – 19.10 µmol/l, total protein – 56.70 g/l, glucose – 4.69 mmol/l, urea – 2.10 mmol/l, total alpha-amylase – 216.0 U/l.

Coagulation profile: PT – 15.2 s, TT – 16.3 s, PT% – 60.50%., PT INR – 1.32 s, fibrinogen – 4.71 g/l, aPTT – 26.40 s.

The patient was re-examined in February 2023 (2 months after the operation) at her place of residence. She had no complaints, and all tests were within normal limits. The endobiliary stent was removed by endoscopists at her residence.

In late April 2023, the patient underwent an operative delivery at 37 weeks and 1 day of pregnancy. The baby’s weight was 2830 g, length was 48 cm, and the Apgar scale was 7/8. Six days after delivery, both mother and child were discharged in satisfactory condition.

Follow-up examinations were conducted 6 and 12 months post-operatively. The patient had no complaints, and there were no clinical or laboratory signs of bile duct obstruction.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of gallstone disease during pregnancy is attributed to physiological changes such as bile stasis and hormonal fluctuations [10]. According to Schwulst and Son (2020), symptomatic gallstone disease (GSD) is a relatively common condition during pregnancy. Acute cholecystitis is the second most frequent non-obstetric indication for surgical intervention, occurring in approximately 1 in 1,600 pregnancies. Ultrasonographic studies have shown that by the third trimester, 8% of pregnant women develop new gallstones, and 1.2% progress to symptomatic disease [16].

ERCP is a widely used invasive procedure and the standard treatment for choledocholithiasis in pregnant women [17, 18].

Iatrogenic perforations increase the risk of morbidity and mortality. After ERCP, complications such as pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pneumoperitoneum are rare, with pneumothorax often associated with pneumoretroperitoneum [10]. During ERCP, air can enter the pleural cavity through three different routes: air from the perforation may travel from the retroperitoneal space into the peritoneum, subcutaneous tissue, mediastinum, and ultimately the pleural cavity. Another mechanism includes air passing through holes in the diaphragm or alveolar rupture [19].

Cirocchi et al. (2020) emphasized that symptomatic or rapidly enlarging choledochal cysts, as well as their complications, may necessitate emergency surgical intervention in pregnant women. However, such procedures are associated with a high risk of complications for both the mother and the fetus, with the mortality rate reaching 7.2% [13]. The likelihood of spontaneous rupture of a cyst is between 1.8% and 2.8% [20].

The main causes of spontaneous cyst rupture include weakening of the cyst wall due to increased intraluminal pressure from stones or strictures, as well as traumatic injury from repeated ERCP or stent placement, which may weaken the wall of the common bile duct [17–20].

According to systematic reviews, endoscopic biliary stenting in cases of biliary obstruction shows high efficacy. It allows rapid restoration of biliary drainage, reduces symptoms, and prevents complications such as purulent cholangitis. The use of plastic and metal stents is the standard approach in treating these conditions [13–20].

In the described clinical case, the choledochal cyst injury after ERCP, complicated by pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum, represents a rare but serious complication. Literature analysis indicates that such complications often arise due to improper technique or perforation of the bile duct wall. In these situations, biliary stenting with subsequent adequate drainage and antibiotic therapy is the main treatment approach [19, 20].

Surgical removal of the choledochal cyst is recommended after childbirth. The choice of treatment depends on several factors, including the presence of cholangitis, the size of the cyst, and the clinical presentation of the choledochal cyst. However, due to the rarity of this condition, no unified standards for patient management exist. Treatment depends on the clinical situation: if the cyst wall is fragile, the patient is hemodynamically unstable, or there is inflammation or bowel edema, drainage of the common bile duct (using a T-tube or percutaneous transhepatic drainage) is required, followed by the final surgery. Alternatively, a single operation with cyst removal and biliary-enteric drainage can be performed if intraoperative conditions allow [20].

For example, Shimizu et al. (2024) reported a rare case of a choledochal cyst with acute cholangitis diagnosed at 37 weeks of gestation. Following cesarean delivery, the patient underwent successful laparoscopic cyst excision and biliary reconstruction, with favorable outcomes observed at a 7-year follow-up [21]. Similarly, Liu et al. (2002) noted that in the postpartum period, the most commonly performed surgical procedure was hepaticojejunostomy (90.7%), while cystogastrostomy (5.5%) and cystoduodenostomy (3.7%) were used less frequently [14].

The gold standard for treating choledocholithiasis in pregnant women is a two-step approach: 1) performing ERCP and papillotomy, and 2) laparoscopic cholecystectomy. If ERCP is not feasible, an alternative to biliary decompression is percutaneous drainage of the bile ducts.

Conclusions

The treatment of complications associated with gallstone disease during pregnancy presents a complex challenge that requires a thorough assessment of risks to both the mother and the fetus. In this case, successful endoscopic treatment of a choledochal cyst complicated by pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax after ERCP in a pregnant woman demonstrated that this technique is effective when performed by experienced specialists.

An experienced physician decided to perform choledochal stenting after perforation based on his professional expertise, and the procedure was successful. When performing ERCP, it is essential to exercise the utmost caution, considering the high risks of damage to the duodenum and bile ducts, especially when choledocholithiasis and choledochal cyst coexist.

This case underscores the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in the management of pregnant women with choledocholithiasis, as well as the need for an individualized assessment of both the patient and the fetus.