Introduction

Pancreatic lesions, regardless of their nature as benign or malignant, provide a substantial therapeutic challenge owing to their anatomical positioning and propensity for aggressive behavior [1]. They exhibit a wide range of neoplastic proliferations, among which pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs) and pancreatic adenocarcinoma raise significant concerns [1]. PNETs are a heterogeneous collection of neoplasms arising from the pancreas’s islet cells [2]. They display considerable variability, resulting in the development of functional or non-functional tumors [2]. Functioning pNETs secrete excessive amounts of specific types of hormones, leading to distinct clinical symptoms [3]. Insulinomas, which cause hypoglycemia, gastrinoma, which causes excessive stomach acid production, and glucagonomas, which causes hyperglycemia, are typical examples of functional pNETs [4]. The malignant potential of non-functional pNETs is broad, ranging from non-infiltrative, slow-growing tumors to locally invasive and quickly metastasizing [2]. This variability makes it difficult to standardize diagnosis, surgical and medicinal therapy, follow-up monitoring, and prognosis [2].

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, which is highly lethal, is characterized by limited treatment choices and poor prognosis [5]. It evades early identification because of the limited manifestation of symptoms during its earliest phases [5]. It is often detected at an advanced stage, when surgical intervention is no longer feasible. The management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma generally encompasses a multimodal approach, including surgical intervention, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies [6]. Despite these treatment modalities, the overall prognosis for patients with this condition remains poor, emphasizing the need for enhanced early detection methods and more effective therapeutic approaches [5, 6].

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has recently become more significant in identifying and treating pancreatic lesions [7]. EUS integrates high-resolution ultrasound imaging with endoscopy, enabling accurate viewing of the pancreas and its surrounding anatomical components [8]. It has facilitated the development of minimally invasive treatments, such as endoscopic ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation (EUS-RFA) and endoscopic ultrasound-guided ethanol ablation (EUS-EA) [9].

EUS-RFA is a medical procedure that uses radiofrequency energy to treat the target lesion selectively [10]. This application of energy induces controlled thermal destruction of the tumor tissue, resulting in its eradication [10]. On the other hand, the EUS-EA technique involves the direct administration of ethanol into the lesion, leading to cell death by dehydration and chemical processes [11]. The EUS-guided RFA/EA approach has the benefit of being simple, quick, and inexpensive, with manageable side effects [12]. Moreover, these techniques may be used for various pancreatic diseases, including pNETs and adenocarcinomas [12]. Nevertheless, more data on these techniques’ safety profile, feasibility, and long-term outcomes are needed. Consequently, this study assessed the safety profile, feasibility, and outcomes of EUS-RFA and EUS-EA of focal pancreatic masses. It sought to make a valuable contribution to the continuous endeavors to enhance the treatment of pancreatic lesions. Moreover, it could improve the overall well-being of individuals diagnosed with pNETs and adenocarcinoma.

Material and methods

Study design

This prospective study included 27 patients, 15 males and 12 females, with a mean age of 36.38 years. All patients had confirmed neoplastic pancreatic focal lesions and were subjected to local ablative therapy between January 2021 and June 2023.

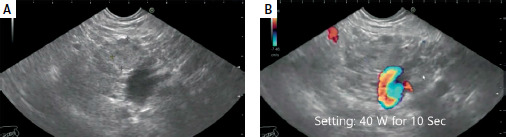

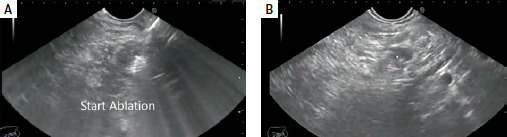

Endoscopic and ultrasonic equipment and procedure. EUS-RFA was conducted in 13 patients; 11 had pancreatic insulinoma, and two had advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The mean size of the masses was 20.6 mm, while that of insulinomas was 17.4 mm. Figure 1 shows the mass (Figure 1 A) and RFA setting (Figure 1 B), Figure 2 A shows the start of ablation, and Figure 2 B shows the lesion demolished. The median number of needle passes was 3, with a range of 1 to 6. RFA was conducted using 19G EUSRA needles from Taewoong Co., Ltd., South Korea. No minor or major complications were observed. EUS-EA was carried out in 14 patients, all of whom had pancreatic insulinoma. The mean size of the masses was 15.3 mm. The median number of needle passes was 2, with a range of 1 to 3. We used 19G and 22G echo tip FNA needles from Cook Company, USA. The mean duration of follow-up was 12.4 months. There was mild to moderate acute pancreatitis in 4 patients in the EUS-EA group; all were relieved by conservative therapy, and no hospital admission was required. No early or late significant complications were reported in the EUS-RFA group. All patient characteristics, lesion characteristics, procedure details, and outcomes were collected and analyzed.

Results

Twenty-seven patients were included in our analysis; 14 were subjected to alcohol injection, and 13 were subjected to RFA. The mean age in the ethanol injection patients was 38.6 years; 13 patients had functioning insulinoma and presented with hypoglycemic episodes and high C-peptide levels, while 1 had non-functioning pNET and presented with abdominal pain. The mean size of the lesions was 15.3 mm; 10 lesions were located in the pancreatic head/neck, 2 in the body, and 2 in the tail. Two needle sizes were used, 22 G in 9 and 19 G in 5 patients. The average volume of alcohol injected was 3 ml. An adequate response to treatment without hypoglycemic manifestations was achieved in 8 (57%) patients, and 2 (14%) patients showed a decrease in the number and severity of episodes. In comparison, 4 (28%) patients did not achieve improvement and were referred for surgery (3 patients) and RFA (1 patient). Post-procedure mild to moderate pancreatitis was noted in 4 patients; all received medical treatment for less than ten days. No major adverse events or recurrence was observed during the mean follow-up period of 9.6 months (Table I).

Table I

Patients subjected to ethanol injection (n = 14): patient and lesion characteristics and procedure details

The mean age of RFA patients was 34.2; 11 patients had functioning insulinoma and presented with frequent hypoglycemia and high C-peptide levels, and 2 had pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and presented with abdominal pain. The mean size of the lesions was 20.6 mm; 6 were located in the head, 4 in the neck, 2 in the body, and 1 in the tail. All lesions were ablated with a dedicated RFA needle (EUSRA, Taewoong Co., Ltd., South Korea), size 19 G. All patients with insulinoma achieved a complete cure (8 patients in 1 session, 2 in 2 sessions, and 1 in 3 sessions). Patients with PDAC showed reduced size after RFA but did not achieve downstaging of their lesions and were then referred for palliative chemoradiation therapy. The mean follow-up period of all patients was 12 ±12.3 months (Table II).

Table II

Patients subjected to radiofrequency ablation (RFA) (n = 13): patient and lesion characteristics and procedure details

Discussion

This study assessed the safety profile, feasibility, and outcomes of EUS-RFA and EUS-EA of focal pancreatic masses. The evaluation is essential for several reasons. It prioritizes patient safety by identifying possible risks and consequences of these therapies, which is critical for evidence-based decision-making [13]. Furthermore, assessing feasibility plays a crucial role in choosing the most appropriate candidates for these therapeutic interventions, considering several aspects, such as the size and location of the lesion. Examining treatment outcomes offers valuable insights into the efficacy of these interventions, enabling the assessment of their ability to accomplish desired objectives such as tumor control and alleviation of symptoms [13]. The findings of this study established that EUS-RFA and EUS-EA could potentially treat lesions and control symptoms. EUS-EA seemed less efficient in managing functional insulinomas, exhibited a relatively low complete cure rate of 57%, and a safety profile that could be enhanced with medical treatment in mild to moderate pancreatitis cases. EUS-RFA demonstrated a higher complete cure rate, 90.9% for insulinomas. However, it could not downstage PDAC patients, underscoring the difficulties in managing this aggressive malignancy.

The treatment responses observed in the EUS-EA and EUS-RFA groups exhibited apparent differences. The EUS-RFA group had a higher complete cure rate of 90.9% among patients with insulinoma. Additionally, most patients (10/11 patients) did not experience recurrent hypoglycemic episodes. This finding implied that EUS-RFA might provide a more robust and effective therapeutic outcome, consistent with previous research [10, 13]. Armellini et al. [13] investigated the use of EUS-RFA for the treatment of pNETs. The findings indicated that for both functioning and non-functioning pNETs, EUS-RFA is a minimally invasive approach with a favorable safety and effectiveness profile [13]. Moreover, the research highlighted the importance of EUS-RFA in treating low-grade pNETs. It implied that it might be a viable substitute for surgery, especially for patients who are not eligible or at high risk for surgical procedures [13].

Nevertheless, the results were less promising for individuals with PDAC, since they did not achieve downstaging of their lesions. This may be due to the aggressive nature of PDAC, which often has more extensive and locally invasive tumors and the potential for metastasis [10, 14, 15]. Downstaging improves respectability, patient quality of life, and overall outcomes. Usually, downstaging requires a multimodal strategy that includes adjuvant treatment after surgical resection to maximize the odds of long-term survival and neoadjuvant therapy to decrease the tumor [16].

On the other hand, the EUS-EA group (the majority had functioning insulinomas) achieved a favorable treatment response and symptom control of up to 57% without experiencing hypoglycemia symptoms. Furthermore, 14% exhibited a reduction in the frequency and severity of episodes. This finding suggests that EUS-EA is a cheap, viable approach for managing the hormonal manifestations linked to functional insulinomas, consistent with other studies that advocated its efficacy in treating these neoplasms [17, 18]. For instance, Choi et al. [17] examined the effectiveness and predictive variables of EUS-EA in the treatment of solid pancreatic tumors, such as solid pseudopapillary tumors (SPTs) and pNETs. The findings showed that for patients who were not fit for surgery or those who declined, EUS-EA could be a feasible alternative. It was noted that pNETs had more significant potential as candidates for EUS-EA and took less time to obtain an objective response. Ethanol administration was a substantial determinant; a dose greater than 0.35 ml/cm3 was linked to shorter times for achieving complete remission and an objective response [17]. Only 2 cases of severe pancreatitis were reported. Although there were some side effects, they were all manageable [17].

Moderate pancreatitis was observed in 4 patients in the EUS-EA group, and all of them were treated within 10 days. No adverse events were reported in EUS-RFA, signifying a promising safety profile. The differences in adverse events might be due to variations in ablation techniques, ablation volume, lesion and patient characteristics, and sample size [19]. The general and chemical nature of EUS-EA may increase complications, including mild to severe pancreatitis. At the same time, the localized and regulated thermal energy delivery of EUS-RFA may help reduce the likelihood of adverse effects [19]. The results highlighted the need to comprehend the risks associated with each ablation technique before considering their use in clinical settings.

There were variations in the types and locations of lesions across the groups. In the EUS-EA group, all patients had functional insulinomas except one, who presented with a non-functioning pNET. The observed lesions had a predominant distribution throughout the head and neck regions of the pancreas. On the other hand, the EUS-RFA group consisted of individuals with both functional insulinomas and PDAC. The lesions were distributed in several locations within the pancreas, with a predominant concentration in the head region. The variations in lesion types and locations highlighted the suitability of EUS-EA and EUS-RFA for various lesion characteristics and anatomical locations [9].

There were certain limitations to the study. The sample size of 27 patients was relatively small and might only partially represent part of the patient population, which reduced its statistical power. Additionally, it was challenging to draw specific outcomes, because the patient population was heterogeneous and included people with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma and pancreatic insulinoma. The rather short mean follow-up period (12.4 months) might have missed late complications or long-term effects. Further prospective and comparative studies involving many patients are needed to investigate and confirm the safety and practicability of using EUS-RFA and EUS-EA to manage focal pancreatic masses, especially for small pNETs with very low malignant potential.

Conclusions

EUS-RFA and EUS-EA can potentially treat lesions and control symptoms. They may be a treatment option for functioning neuroendocrine tumors, especially in patients with poor surgical risk or those refusing major surgery. EUS-RFA is a more promising and safer technique for managing functioning insulinomas. However, it cannot downstage PDAC patients. EUS-EA seems less efficient and exhibits a relatively low safety profile that can be enhanced with medical treatment in mild to severe pancreatitis cases. Further research, especially prospective and comparative studies involving a large number of patients, is needed to clarify the efficacy and safety of EUS-RFA and EUS-EA as an alternative to surgery in patients with pancreatic masses, especially functioning NETs such as insulinomas.