Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), encompassing ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), is a chronic inflammatory condition imposing a significant morbidity and healthcare burden [1–4]. Achieving endoscopic remission is a crucial therapeutic goal, strongly associated with improved patient outcomes [5]. Current methods for predicting endoscopic remission are limited, underscoring the need for novel biomarkers [6].

Fecal calprotectin (FC) is a well-established biomarker for IBD, owing to its specificity for inflammation, non-invasive measurement, correlation with disease activity, ability to differentiate IBD from other conditions (including gut-brain axis disorders), and utility in monitoring treatment response. However, FC is not a perfect marker; while it correlates with disease activity, it is not diagnostic for IBD alone, and other factors can cause transient elevations [7, 8]. Therefore, it is most effective as part of a comprehensive diagnostic and management strategy, used in conjunction with clinical evaluation and other tests.

One potential additional biomarker is fecal butyric acid (C4), the usefulness of which has been suggested in only one recent study. Kaczmarczyk et al. investigated fecal short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) profiles in patients with active and inactive UC and CD, finding significantly lower C4 levels in patients with active disease compared to controls. They also observed significantly higher lactic acid levels in patients with active UC, correlating positively with C-reactive protein (CRP) [9]. These findings suggest that altered SCFA profiles, particularly reduced C4 and elevated lactic acid in active UC, may be valuable markers of IBD activity.

Considering this, this study aims to evaluate the utility of C4 as a fecal biomarker for UC.

Aim

The primary endpoint of this study was to assess fecal C4 concentration in patients with UC and to evaluate the correlation of this parameter with the occurrence of endoscopic remission, defined as a Mayo score of 0. The secondary endpoint was to assess the correlation between C4 and FC.

Material and methods

Study design

This multicenter, prospective study evaluated the utility of C4 in predicting endoscopic remission in patients with UC. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the National Medical Institute of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration in Warsaw (approval code 35/2020, approved/dated March 4, 2020).

Participants and inclusion/exclusion criteria

Between April 2021 and April 2023, participants were recruited from UC patients referred to the Department of Gastroenterology and Internal Medicine, National Medical Institute of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration in Warsaw, and the Department of Digestive Tract Diseases, Medical University of Lodz. Gastroenterologists from these departments conducted the recruitment. Inclusion criteria included: age of 18 years or older; UC diagnosis confirmed by endoscopic and histological examination (according to the Polish Society of Gastroenterology and European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation guidelines) at least 1 year prior to study enrollment; provision of written informed consent; and stable UC therapy (no changes in medication type or dosage).

Exclusion criteria included: rectal-limited UC (proctitis or Montreal classification E1); treatment escalation or addition of therapy within 24 weeks prior to study enrollment including topical, rectal mesalazine; oral, topical corticosteroids; oral, topical budesonide MMX; immunosuppressants (thiopurines, methotrexate, ciclosporin); advanced therapies like biologics (anti-TNF-α, vedolizumab, ustekinumab) and small molecule inhibitors (tofacitinib, filgotinib, upadacitinib, ozanimod); antibiotic use during or within 8 weeks prior to the study; pro-/pre-/synbiotics, SCFA, or other supplements within the last 12 weeks; significant dietary or lifestyle changes during the study; COVID-19 infection during or within 8 weeks prior to recruitment; other gastrointestinal diseases; history of colostomy or cancer; hospitalization during the study; pregnancy and lactation.

Evaluation of butyric acid (C4) concentrations

C4 concentrations were measured by mass spectrometry. Fecal samples (60 mg wet weight) were dissolved in 300 µl methanol, vortexed (1600 rpm for 5 min), sonicated (30 min at room temperature), and vortexed again. After centrifugation (18,000 x g for 15 min at 4°C), supernatants were transferred to vials and stored at –80°C until analysis. Before chromatographic analysis, samples underwent further centrifugation (18,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C). Analysis was performed using a TripleTof® 6600+ mass spectrometer with separation on an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 (C18) column (1.8 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm, Waters, Ireland) at 45°C. The injection volume was 2 µl. A gradient elution was employed using water (A) and methanol (B), both containing 0.04% formic acid, at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min (0–6 min: 5% to 100% B; 6–10.50 min: 100% B; 10.50–10.51 min: 100% to 5% B; 10.51–15 min: 5% B). Electrospray ionization (ESI) at 3500 V (positive and negative modes) was used, with nitrogen as the nebulizing and drying gas (source temperature: 175°C; gas flow: 12 l/min). Data were analyzed using the XCMSplus metabolomic analysis system.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R version 4.4.2. Numeric variables were described using the mean and standard deviation or the median and interquartile range, depending on normality. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Group comparisons used Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, Pearson’s χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Effect sizes were reported as the mean or median difference for numeric variables and Cramer’s V for categorical variables. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis with the Youden index determined the optimal C4 cutoff for predicting endoscopic remission. Spearman correlation assessed the correlation between C4 and fecal calprotectin. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

This study included 100 patients with UC. The mean age was 41.83 ±11.43 years (range: 24–70 years), with 39% female. The median body mass index (BMI) was 23.99 kg/m2. Sixty-one percent had extensive disease (E3), and 39% had left-sided disease (E2). Median disease duration (to 2024) was 10 years. Ninety-six percent received mesalazine, 55% received immunosuppressants, 29% received glucocorticoids (GCS), and 12% received budesonide. Eighty-four percent received advanced therapies (details in Table I). The mean C4 concentration was 2.77 ±4.90 nM/mg; the median was 0.84 nM/mg.

Table I

Characteristics and comparison of study groups

[i] M – mean, SD – standard deviation, Me – median, IQR – interquartile range, MD – mean or median difference (with endoscopic remission vs. without endoscopic remission), CI – confidence interval. Numeric variables were compared with t-Student test (age and TMS) or Mann-Whitney U test (BMI, duration of disease, C4 and calprotectin). Categorical variables were compared with Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. *Proportions counted with reference to patients with any biological drug.

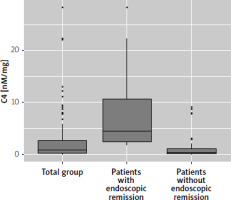

Patients were divided into remission (n = 26, Mayo score 0) and non-remission (n = 74) groups. A significant difference in Mayo score was observed between groups (p < 0.001). Significant differences were also found in total Mayo score (TMS), C4 concentration, and advanced therapy use. Patients in remission had lower TMS (mean difference [MD] = –3.37; 95% confidence interval [CI]: –4.08 to –2.66; p < 0.001) and higher C4 concentration (MD = 4.05; 95% CI: 2.44 to 5.71; p < 0.001). Advanced therapy use was less frequent in the remission group (69.2% vs. 89.2%; p = 0.028), representing a small to moderate effect size (Cramer’s V = 0.24; 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.46). Table I details baseline characteristics. Figure 1 shows the distribution of C4 concentrations.

Figure 1

Boxplot chart presenting distribution of C4 in the total study group and in split to patients with and without endoscopic remission (defined as Mayo Score 0). Statistically significant difference (p < 0.001)

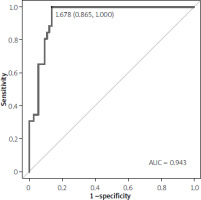

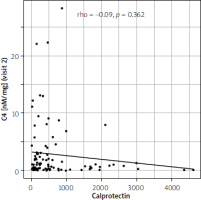

ROC analysis identified the optimal C4 cutoff for predicting endoscopic remission. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.943 (95% CI: 0.897–0.980; p < 0.001), indicating excellent prognostic ability. The optimal cutoff was 1.68 nM/mg, with 100% sensitivity and 86% specificity (Table II). The ROC curve is shown in Figure 2. Spearman correlation analysis showed no significant association between C4 concentration and FC (rho = –0.09, p = 0.362; Figure 3).

Table II

Outcome of receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis for concentration of C4 as prognostic of endoscopic remission

| Variable | Optimal cut-off | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C4 [nM/mg] | 1.68 | 0.943 (0.897; 0.980) | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 1.00 | 0.90 | < 0.001 |

Discussion

This study investigated the potential of C4 as a predictor of endoscopic remission in patients with UC, revealing a strong association between elevated C4 levels and achieving remission. Our findings contribute significantly to the growing body of research exploring the role of gut microbiota and its metabolites in IBD pathogenesis and treatment response [10].

The observed higher C4 concentrations in patients achieving endoscopic remission (Mayo score 0) are particularly noteworthy. This finding aligns with the established anti-inflammatory properties of butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid produced by gut microbiota [11–14]. Butyrate’s ability to enhance gut barrier function, modulate immune responses, and inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production suggests a plausible mechanism by which it might contribute to remission [15, 16]. The significant mean difference in C4 levels between the remission and non-remission groups (MD = 4.05 nM/mg, p < 0.001), coupled with the excellent performance of C4 in ROC analysis (AUC = 0.943, p < 0.001), strongly supports its potential as a valuable predictive biomarker. The identified optimal cutoff of 1.68 nM/mg, yielding 100% sensitivity and 86% specificity, further emphasizes this potential. A test with such high sensitivity could prove invaluable in identifying patients likely to respond well to specific therapies, aiding in personalized treatment strategies [17].

The observed inverse relationship between the use of advanced therapies and the achievement of endoscopic remission is intriguing. Although statistically significant (p = 0.028), the small to moderate effect size (Cramer’s V = 0.24) suggests that other factors are likely at play. This finding could potentially indicate that patients who achieve remission naturally exhibit higher baseline C4 levels, rendering them less reliant on advanced therapies. Further research is needed to clarify this complex interplay between C4 levels, advanced therapy response, and the underlying mechanisms governing endoscopic remission [18–20].

Our study’s findings are also relevant in the context of the well-established biomarker, FC. While FC is widely used to assess IBD activity, its limitations, including its lack of specificity and susceptibility to influences beyond intestinal inflammation, are recognized. The lack of a significant correlation between C4 and FC in our study suggests that C4 may offer a complementary perspective, potentially providing additional diagnostic and prognostic information not captured by FC alone. This lack of correlation underscores the value of exploring additional biomarkers to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the intricate processes governing IBD remission. However, we acknowledge that the lack of a significant correlation may be related to the study population, as patients experiencing flares presented with mild-to-moderate disease activity. This is further supported by the comparison of patients with and without endoscopic remission, where FC levels were not significantly different (334.00 vs. 311.00; p = 0.245) [6, 7].

The strength of our study lies in its robust methodology. The prospective design, alongside rigorous inclusion and exclusion criteria, was crucial in minimizing confounding factors and ensuring homogeneity within the study population. The utilization of mass spectrometry for accurate C4 quantification, along with the application of appropriate statistical analyses, further enhanced the validity of our results. However, this study also has limitations. The relatively small sample size warrants caution in generalizing these findings. Additionally, the study population only consisted of patients with UC. Further studies with larger, more diverse populations, including patients with CD, are crucial to validate these findings and assess their generalizability across various IBD phenotypes and disease severities. Future studies should also investigate the longitudinal changes in C4 levels in response to different treatment modalities, which could further illuminate its utility in monitoring disease activity and guiding treatment decisions. Exploring the underlying mechanisms through which C4 influences UC remission could also provide significant insights into disease pathogenesis and offer new therapeutic avenues. Additionally, investigation into the interplay between gut microbiome composition, butyrate production, and C4 levels in various IBD phenotypes is merited.

Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence for the potential of fecal butyrate (C4) as a novel, non-invasive biomarker for predicting endoscopic remission in UC. The high sensitivity and specificity demonstrated by C4 highlight its potential to improve clinical decision-making and personalize IBD management. Further research should focus on validating these findings in larger, prospective studies and exploring the underlying mechanisms and clinical applications of this promising biomarker.