INTRODUCTION

The article presents the case of ischemic stroke in the context of specific accompanying risk, factors such as heart failure and implanted left ventricle assist device (LVAD), and the results of invasive treatment with mechanical thrombectomy (MT).

The treatment of ischemic stroke in our patient was a significant challenge. In our opinion, due to the increasing number of patients with heart failure, treated with mechanical circulatory support, the description of each case of a successfully treated patient in the acute phase of ischemic stroke is worth circulating among cardiologists and neurologists.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 58-year-old patient with dilated cardiomyopathy, fitted with permanent atrial fibrillation (AF) with implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD), who underwent LVAD implantation in 2020 due to advanced heart failure as a bridge to heart transplantation, admitted to the intensive cardiac care unit (ICCU) one year after this procedure was performed. The cause of hospitalization was six episodes of AF, falsely detected by ICD as ventricular fibrillation (VF), with subsequent provocation of unnecessary defibrillator discharges and, in consequence, real episodes of VF. The hybrid third-generation centrifugal pump was a mechanism of LVAD functioning. The patient was treated with aspirin at a dose of 75 mg and warfarin with INR at admission – 2.36. The power consumption by LVAD was at the level of everyday monitoring.

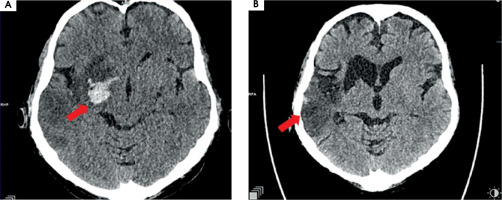

Twelve hours after admission to ICCU, in the presence of medical staff, the patient experienced symptoms of the stroke such as dysarthria, drooping of the corner of the mouth at the left side, and severe weakness of the left upper and lower limbs. The computed tomography (CT), which was performed immediately, showed that a high attenuation of the right middle cerebral artery (RMCA) was present (Figure IA). Angio-CT of cerebral arteries confirmed the occlusion of RMCA at segment M1/M2 about 6.5 mm from the origin of RMCA (Figure IB). The VRT (volume rendering technique) reconstruction of cerebral arteries was performed based on angio-CT (Figure IC).

As soon as was possible, i.e. less than four hours from the beginning of the stroke symptoms, the patient was transferred to the clinical centre for invasive stroke treatment. On admission to the neurological department the patient was assessed at 15 points according to the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). The patient was conscious (0 pt NIHSS), answered simple questions correctly (0 pt NIHSS), followed simple instructions (0 pt NIHSS), presented total gaze paresis to the left (2 pts NIHSS) without visual loss (0 pt NIHSS), had partial paralysis of the left facial nerve (2 pts NIHSS), mild dysarthria (1 pt NIHSS), complete paralysis of the left upper (4 pts NIHSS) and the left lower (4 pts NIHSS) limbs, moderate sensory loss in the left limbs (1 pt NIHSS), and neglect syndrome in sensory modality (1 pt NIHSS). He was qualified for MT treatment.

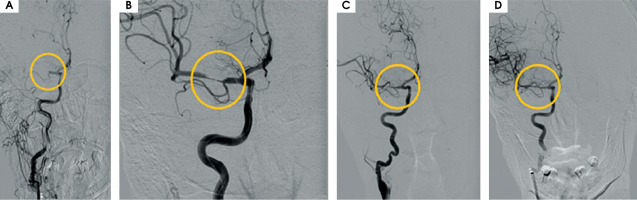

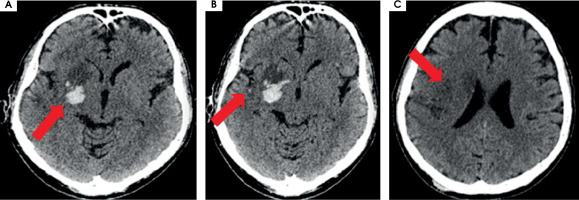

After MT the blood flow in the artery was returned with TICI 3 (Figure II). The day after the MT, control CT showed haemorrhagic foci (Figure III). The patient returned to the ICCU three days later. His neurological status was the same as before the MT of RMCA. In repeated CTs of the brain, haemorrhagic foci were still present (Figure IVA). In the following days of hospitalization, the resolution of haemorrhagic and evolution of ischemic cerebral lesions were observed (Figure IVB).

Because of the elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) to 30 mg/l (with reference value ≤ 5 mg/l) and white blood cells (WBC) to 18 × 109/l (with reference value ≤ 10 × 109/l), blood samples for cultures were taken on the day of the stroke. Three days later, the presence of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus with methicillin resistance (MRCNS) was discovered. Therapy with vancomycin was started. Additionally, thyrotoxicosis was diagnosed, and treatment with thiamazole was necessary. Rehabilitation began soon after the invasive stroke treatment and was continued throughout hospitalization and later in the rehabilitation department in our hospital.

Figure I

A) Computed tomography without contrast – hyperdense right middle cerebral artery (RMCA). B) Angio-CT – occlusion of RMCA in M1/2 segment. C) VRT (volume rendering technique). Arrows show pathological lesions

In good condition – with neurological improvement, normal eye movements (0 pt NIHSS), partial facial palsy on the left (2 pts NIHSS), mild dysarthria (1 pt NIHSS), mild paresis in the left upper (1 pt NIHSS) and left lower (1 pt NIHSS) limbs, mild sensory loss on the left limb (1 pt NIHSS), neglect syndrome in sensory modality (1 pt NIHSS) – the patient scored a total of 7 points in NIHSS, and was transferred from the ICCU to the cardiology department specialized in heart failure treatment eight days after the stroke.

Figure II

A) Right middle cerebral artery (RMCA) occlusion: 7 mm from its ostium from the right internal carotid artery – TICI 0. B) Mechanical thrombectomy performed twice using stent retriever Solitaire X 6 × 40 mm – branches of RMCA are opened, still present thrombus which narrowing lumen of RMCA in segment M1. C) After first aspiration of thrombus (catheter – ACE68). D) After second aspiration of thrombus – final result TICI 3

Figure III

Scans from control computed tomography of the brain performed the day after the procedure of thrombectomy. A) On the right side of the brain, in deep structures, hyperdense haemorrhagic foci are seen, with the greatest one 20 × 21 × 15 mm and a smaller satellite. B) Surrounding the M1/M2 segment of right middle cerebral artery, probably minor subarchnoid haemorrhage in the lateral sulcus on the right side is present. C) Acute ischemic lesions located cortico-subcortically in the right hemisphere, including part of the frontal, occipital, and temporal lobe and also thalamus, the islet, caudate nucleus, mass effect is present as a narrowed frontal horn of the right ventricle and a narrowed sulcus above the area of stroke

COMMENT

While LVAD implantation is a proven and increasingly used method of treating patients with advanced heart failure, it must be performed in cardiological centres with experience in this area; for this reason, it is still the case that too small a number of patients undergo this procedure. On the one hand, it is a life-saving method of treatment, in some cases a bridge to heart transplantation or as destination therapy; on the other hand, patients with implanted LVAD have an increased risk of life-threatening complications such as problems with driveline (fracture, infection), device failure, embolism including ischemic stroke (about 10% in the first year of support), arrhythmia (atrial, ventricular), thrombus (in device 1.5-13%) and haemorrhage, including the intracranial variety (30-60%) [1, 7]. It has been shown that rates of ischemic and haemorrhagic strokes are equal and that they are most likely during the peri-implantation period and in the first year of LVAD therapy [2]. It was found that strokes occur more than twice as frequently in patients with end-stage heart failure managed with mechanical support, compared with those treated only with optimal pharmacological therapy [8]. The risk factors for stroke are older age, severity of heart failure, hypertension, history of diabetes, prior stroke, hypercoagulable state, and female gender; also significant are perioperative factors such as use of aortic cross clamping with cardioplegic arrest and post-operative factors such as duration of mechanical support, infections, unstable INR values, and high systolic blood pressure after the LVAD implantation [3, 9-12]. INTERMACS registry published in 2017 revealed stroke as a main reason of death between 6 and 24 months after start of the support with LVAD [13]. The potential risk factors for ischemic stroke in our patient were the presence of the implanted device, atrial fibrillation, and bacteraemia confirmed just after stroke treatment.

Among the 14,607 patients implanted with LVAD between 2015 and 2019, the percentages of stroke-free patients 12 months, 24 months and 60 months following the procedure were 87.3, 81.3 and 68 respectively [5, 14]. Although the hybrid third-generation centrifugal device which was implanted in our patient was shown in ENDURANE trial to be “noninferior” to the second-generation axial-flow pump regarding a composite endpoint of survival free from disabling stroke or need for device replacement at 2 years, due to increased risk of neurological adverse events when compared to other commercially available devices the distribution and implantation of this type of LVAD were limited in June 2021 [1, 15, 16]. Pump thrombosis was seen with high frequency with both types LVAD [1, 16]. This serious problem led to changes in the recommended management of patients, as well as design modifications for subsequent devices [1, 16]. At that time, antithrombotic treatment with a vitamin K antagonist (INR between 2 and 3) and low dose of aspirin was recommended, and this therapy was also applied our patient [17]. Currently, according to the ARIES HM3 study results, aspirin may be removed safely from the antithrombotic regimen in the case of the most recent generation of devices [18].

Though in the case of our patient, the device was implanted when LVADs had been regarded as systems causing a high risk of thrombosis, fortunately at admission, the power consumption of the LVAD – a very sensitive parameter of LVAD thrombosis, was at a normal level.

In the general population, AF is one of the most important causes of stroke; it is responsible for 1.27 cases/per 100 person/year [19]. Ischemic strokes associated with AF are usually caused by thrombus formation in the heart, which easily moves to a large cerebral artery [20]. For this reason, AF-related strokes tend to be more severe and more often fatal [20]. Additionally, greater disability, worse functional outcomes, and increased mortality compared with strokes from the other causes are observed [20].

The risk of infection in LVAD patients is between 25-58% and should always be considered as a reason for the worsening of a patient’s condition [21, 22]. Infection and dehydration in the course of inflammation can also increase the risk of ischemic stroke.

According to guidelines published by European Stroke Organisation (ESO) in 2021 and by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) in 2019 (both sets of recommendations were available at the time of our patient’s stroke), patients with acute ischaemic stroke of < 4.5 h duration should be treated with the administration of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase (0.9 mg/kg) (Class I, Level A) [23, 24]. These guidelines recommend that patients eligible for i.v. alteplase should receive it even if endovascular therapies (EVTs) are being considered (Class I, Level A) [23, 24].

In 2023, the European Stroke Organization (ESO) issued a recommendation for i.v. tenecteplase (0.25 mg/kg) as an alternative to i.v. alteplase in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke (moderate evidence, strong recommendation) [25].

Meanwhile, in 2022 the ESO and European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) recommended intravenous thrombolysis plus MT over MT alone for patients with acute ischaemic stroke (≤ 4.5 hrs of symptom onset), with anterior circulation large vessel occlusion and who are eligible for both treatments (moderate evidence, strong recommendation) [26].

On the other hand, intravenous thrombolysis is potentially harmful and should not be administered in patients with coagulopathy, defined as platelets < 100 000/mm3, INR > 1.7, aPTT > 40 s, or PT > 15 s [24]. In our patient fibrinolytic therapy was contraindicated due to vitamin K antagonist treatment, which is an obligatory in LVAD patients, especially with achieved therapeutic INR values [2, 17].

According to the already-mentioned AHA/ASA guidelines published in 2019, patients should receive MT with a stent retriever if they meet all the following criteria: prestroke mRS (Modified Rankin Scale) score of 0 to 1; causative occlusion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) or middle cerebral artery (MCA) segment M1; age ≥ 18 years; NIHSS score of ≥ 6; ASPECTS (Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score ) of ≥ 6; and treatment can be initiated (groin puncture) within 6 hours of symptom onset (Class I, Level A) [24]. The use of MT with stent retrievers may be reasonable for carefully selected patients with acute stroke who have causative occlusion of the MCA segment M2 or MCA segment M3 portion of the MCAs (Class IIa, Level B-randomized) [24].

According to the guidelines our patient met criteria of EVT and for this reason the endovascular MT was performed.

Although endovascular MT is a recommended treatment for acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion, it is associated with a number of intra-procedural complications: vessel or nerve injury, access-site hematoma or infection, vasospasm, arterial perforation and dissection, or post-treatment complications: symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage; subarachnoid haemorrhage; and embolization to target or another vessel territory. Symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage after MT occurs in 2-14% of cases and raises the likelihood of poor functional outcomes and mortality [27, 28]. However, regardless of the risk of potential complications, the benefit of MT treatment in acute ischemic stroke is still greater than abandonment of such treatment and may give the patient a chance to return to functionality.

Unfortunately, the guidelines presented do not mention stroke in patients with LVADs in the context of indications for MT. Management of stroke in patients with LVADs is challenging due to not fully explored risk of complications yet. Furthermore, this group of patients has been excluded from clinical trials. In LVAD patients little is known about the treatment of stroke, or short-term and long-term outcomes, especially with regard to the efficacy of neuroendovascular techniques and their complications and the functional prognosis after stroke [29].

In 2016, a paper was published which presented a review of the safety and effectiveness of the intervention and potential complications in 5 cases of patients with LVAD and stroke who underwent neuroendovascular interventions [29].

No significant complications occurred as a result of the intervention, all cases showed at least a 4-point improvement in the NIHSS scale, and no patient had a symptomatic haemorrhage.

Neuroendovascular intervention was thus found to be safe in this group of patients and could potentially improve stroke outcomes [29].

Only one, larger group (consisting of 794 patients) with LVAD and stroke treated with MT has been described – in 2022, by Ibech et al. [30]. Among these patients in 61% stroke occurred post-operatively. The authors found that MT is a beneficial method of treatment for patients with pre-existing LVADs and may result in rates of good outcome similar to those in the general population of stroke patients [30]. A worse prognosis after MT in stroke was observed in a post-operative LVAD subgroup. In these patients, the risk of in-hospital death after MT with an adjusted odds ratio was 8.66, and the confidence interval 1.46-51.3 [30]. Although the reported experience with endovascular therapies in patients with LVAD and stroke to date is minimal, there are no specific LVAD-related clinical aspects that would exclude EVT as a treatment in eligible patients [30].

The case of our patient is an example of an extremely high risk of stroke despite adequate antithrombotic treatment, and according to NIHSS his predicted functional outcome after the stroke was rather unfavourable. Fortunately, the precisely known time of the beginning to the stroke enabled a quick and effective invasive intervention. Because of the invasive treatment and subsequent rehabilitation his status finally allowed for the performance of a heart transplant a few months later.

The case presented is an example of difficulties in non-cardiological treatment decisions in patients with LVAD, especially due to the still-insufficient knowledge about possible complications and the side effects of the implementation of the therapy. Multidisciplinary site expertise in LVAD management is ideal, but sometimes difficult to achieve. Fortunately, there is a very well-functioning 24-hour, remote system of supervision of patients with LVADs with the monitoring of all important device parameters, which enables the safe care of patients. What is more, patients and doctors can at any time ask for help or the explanation of unforeseen symptoms or device alarms. We hope that our case will be a good example of successful cooperation between cardiologists and neurologists in the management of serious events such as ischemic stroke.